Have you ever finished a book, closed the cover, and just sat there for a moment, thinking about the journey you’ve just taken? Or maybe you’ve binge-watched an entire season of a show in a weekend, completely lost in its world, its characters, its drama. Stories are like oxygen for our minds. We consume them constantly. But have you ever stopped to wonder where it all began? Not just your favorite story, but the first story? The first time someone decided that a tale was so important, so powerful, that it couldn’t just be spoken and risk being forgotten. It had to be written down.

What would that story even be about? Would it be a love story? A ghost story? And what would compel someone, in a world without paper, without pens, without keyboards, to go to the incredible effort of pressing thousands of tiny marks into wet clay just to save a narrative from the winds of time? What could possibly be so important? Well, it turns out the world’s first great literary hero wasn’t a flawless superhero or a charming prince. He was a tyrannical, grief-stricken king terrified of dying. And his story, the first epic adventure ever written, asks the same question that echoes in our hearts today: in the face of our own mortality, how do we live a meaningful life?

To find the answer, we have to travel back. Way back. Back past the Romans, past the Greeks, back to the sun-scorched earth between two rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates. Welcome to Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization. Welcome to the world of the first scribes.

Before the Story, There Was the Shopping List

Let’s be honest. Literature, in all its profound glory, had a rather unglamorous birth. It wasn’t born in a flash of divine inspiration about the human condition. It was born out of bureaucracy. It was born because somebody needed to keep track of their beer.

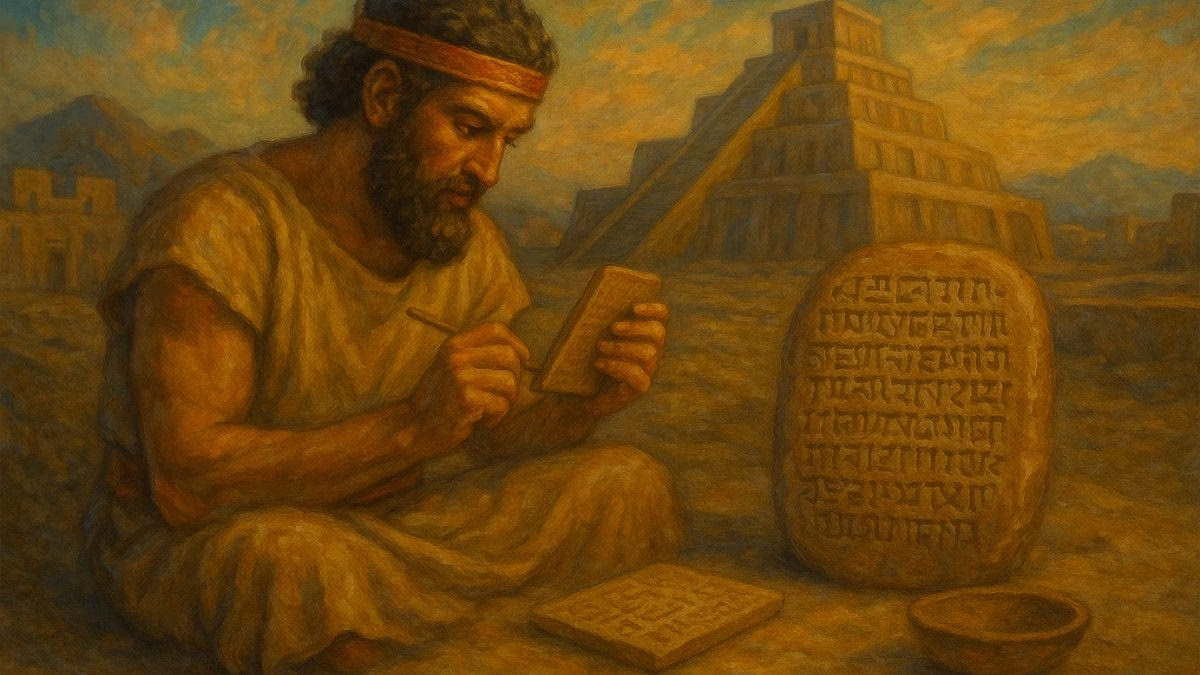

Picture the scene, around 5,000 years ago in a bustling Sumerian city like Uruk, in modern-day Iraq. The city is growing. There’s trade, there are temples, there’s a government. And with all that comes… administration. You’ve got storehouses full of grain, herds of sheep, and temple workers who need to be paid their daily ration of bread and, yes, beer. The Sumerians were fantastic brewers.

Now, if you’re the guy in charge of the royal warehouse, you have a problem. How do you remember that you received 37 sheep from Farmer Ur-Namma on Tuesday, but sent out 15 jars of barley to the temple on Wednesday? Human memory is a leaky bucket. You need a system. A permanent record.

And so, writing was invented not for poetry, but for paperwork. The world’s first accountants were the world’s first writers. They took a lump of wet clay, shaped it into a palm-sized tablet, and used a reed, cut from the riverbank, to press marks into it. The tip of the reed made a distinctive wedge-shaped impression, which is why we call this script cuneiform, from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge.”

Initially, these were simple pictures, or pictograms. A stylized drawing of a head of barley next to a symbol for a number. A stick figure of a person next to a jar, meaning a ration. It was practical, it was effective, and it was revolutionary. For the first time in human history, information could exist outside of a single person’s brain. It could be stored, verified, and transported. It was a technology as game-changing as the internet. But it was still, essentially, a glorified spreadsheet. How on earth do you get from “five goats” to a heart-wrenching story about a king’s love for his friend and his terror of the abyss?

When Numbers Learned to Sing

The leap from accounting to art happened slowly, over centuries. The key was a shift in what the cuneiform wedges represented. Gradually, the symbols stopped being just pictures of things and started representing the sounds of the Sumerian language. This is the difference between drawing a picture of an eye to mean “eye,” and using the picture of an eye to represent the sound “I.”

This phonetic leap was everything.

Once your script can capture the sounds of spoken language, you can write down anything you can say. You can record laws, like the famous Code of Hammurabi. You can write letters to faraway relatives complaining about the quality of copper ore they sent you (we actually have these, some of the world’s first customer complaint letters!). You can write down hymns to your gods and goddesses, praising the mighty Inanna or the fearsome Enlil. And you can write down the stories you’ve been telling around the fire for generations.

This new technology required specialists. It created a new class of people: the scribes. Becoming a scribe was no easy task. It meant years of grueling education in a school called an edubba, or “tablet house.” Young boys—and very rarely, girls—would spend their days from sunup to sundown learning the hundreds, even thousands, of complex cuneiform signs.

We have clay tablets written by these students, and they paint a vivid picture of school life. They complain about their teachers, who were quick to use a cane for any mistake. They practiced writing proverbs, like “He who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn.” And they copied, over and over and over again, the great stories of their culture.

It was in these tablet houses, through the tired hands of countless students and masters, that simple record-keeping was transformed into literature. It was here that the tales of gods, monsters, and heroes were chiseled into a form that could, with a bit of luck, last forever. And the greatest of all these tales was the story of a king who ruled the city of Uruk. The story of Gilgamesh.

Enter Gilgamesh: The Hero We Didn’t Know We Needed

The Epic of Gilgamesh, as we have it today, is a patchwork quilt, pieced together from fragments of tablets discovered over the last 150 years. It’s a detective story in itself, a puzzle with missing pieces. But the story it tells is remarkably complete and devastatingly modern.

It begins by introducing its hero, Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. And right from the start, we know this is no fairy tale. Gilgamesh is, to put it mildly, a jerk. The epic tells us he is two-thirds god and one-third man, which makes him supernaturally strong and powerful, but also mortally flawed. He is arrogant, restless, and abusive. He storms through his city, taking whatever he wants. The text says he “leaves no son to his father” and “leaves no girl to her mother,” which scholars interpret to mean he was using his royal power to sleep with new brides on their wedding night and conscript young men for endless, brutal construction projects. The great walls of Uruk, which he built, are a monument to his ambition, but also to his tyranny.

The people of Uruk are suffering. They cry out to the gods for help. “This Gilgamesh,” they complain, “he’s out of control! Can’t you create someone who can stand up to him? A rival, a counterweight, to keep him busy so we can get some peace?”

The gods listen. The goddess of creation, Aruru, takes a pinch of clay, moistens it with her spit, and forms a new being. A wild man. His name is Enkidu.

A Wild Man, a Taming, and the Ultimate Bromance

Enkidu is Gilgamesh’s opposite in every way. Where Gilgamesh is the product of the city, of civilization, Enkidu is a child of nature. He is covered in shaggy hair, his “hair is as long as a woman’s.” He lives in the wilderness with the animals. He eats grass alongside the gazelles and drinks from their watering holes. He is pure, untamed life force. He doesn’t even know what bread is.

His existence is discovered when a trapper sees this wild man breaking his traps, freeing the animals. The trapper, terrified, goes to Uruk and tells King Gilgamesh about this strange creature. Gilgamesh, ever the strategist, devises a plan that is pure Mesopotamian genius. He won’t send an army. He’ll send a woman.

He sends Shamhat, a temple prostitute or priestess. Her role in this story is profound and often misunderstood. Her job isn’t just to seduce Enkidu; it’s to civilize him. She meets him at the watering hole and, as the epic puts it, for six days and seven nights, they are together. Through this extended encounter, she teaches him about humanity. After his time with her, he tries to return to his animal friends, but they no longer recognize him. The gazelles flee from him. He has changed. He has lost his wild speed, but he has gained something else: “he had wisdom, broader understanding.”

Shamhat then completes his education. She clothes him, teaches him to eat bread and drink beer—the staples of civilized life. Enkidu, the man who once ate grass, gets drunk for the first time and feels joyful. He has become a man. Shamhat tells him of the great city of Uruk and its powerful, arrogant king, Gilgamesh. Enkidu, full of his newfound strength and a desire to test it, decides he will go to Uruk and challenge this tyrant.

The confrontation is inevitable. Enkidu arrives in Uruk and stands in the doorway of a wedding house, blocking Gilgamesh’s path as he comes to claim his “right” to the bride. They grapple. The epic describes a titanic wrestling match. They crash through the doorway, shaking the very foundations of the city. Gilgamesh, for the first time in his life, has met his equal.

In the end, Gilgamesh manages to throw Enkidu. But in that moment of victory, his anger vanishes. He looks at this incredible man, the only person in the world who could match him, and instead of fury, he feels respect. And Enkidu, in turn, acknowledges Gilgamesh’s strength. They embrace. And just like that, the rivalry is over. The epic says, “They kissed each other and became friends.”

This is the turning point. Gilgamesh has found his soulmate, his other half. His restless, destructive energy now has a focus. And what do two super-strong best friends with a god complex do for fun? They decide to go on an adventure. A really, really bad idea of an adventure.

Let’s Go Slay a Monster (What Could Go Wrong?)

Gilgamesh, still driven by his need to make a name for himself, declares their mission: they will travel to the great Cedar Forest, kill its monstrous guardian, Humbaba, and cut down the sacred trees.

Enkidu, who knows the wilderness, is horrified. “No,” he says, “this is a terrible idea. Humbaba isn’t just some monster. The god Enlil, ruler of the earth, appointed him to guard the forest. His voice is the flood, his breath is fire, his stare is death. We can’t win.”

But Gilgamesh is high on the power of friendship. He’s invincible. He gives a rousing speech about how life is short, and the only thing that lasts is a glorious reputation. He convinces Enkidu, against his better judgment, to come with him.

Their journey to the Cedar Forest is epic in itself. They cross seven mountains, and the descriptions of the landscape are some of the earliest nature poetry in existence. When they arrive, they are awestruck by the beauty and sheer size of the cedars, “their shade was good, full of delight.” But the guardian, Humbaba, is truly terrifying.

The battle is immense. The sun god, Shamash, sends great winds to aid Gilgamesh and Enkidu, trapping the monster. Defeated, Humbaba pleads for his life. He offers to be Gilgamesh’s servant, to give him all the sacred trees he wants. Gilgamesh is moved, on the verge of showing mercy. But Enkidu, ever the pragmatist, urges him on. “Don’t listen to him! Kill him now before he can escape!”

Gilgamesh delivers the final blow. They cut off Humbaba’s head and chop down the cedars. They have achieved their glorious victory. They have defied a god’s decree and killed his servant. They float back to Uruk on a raft made of the precious wood, feeling like masters of the universe. Their triumph, however, will be short-lived. Hubris, as the Greeks would later teach us, always has a price.

Never Scorn a Goddess

Back in Uruk, Gilgamesh, fresh from his victory, washes himself, puts on his finest robes, and polishes his crown. He looks so magnificent that he catches the eye of a very powerful admirer: Ishtar, the goddess of love, fertility, and war. A goddess you really don’t want to mess with.

Ishtar proposes marriage. “Be my husband, Gilgamesh!” she says, promising him a chariot of lapis lazuli and gold, dominion over all other kings, and endless abundance.

This should be the greatest moment of Gilgamesh’s life. But instead of politely declining, he launches into one of the most brutal, ill-advised rejections in all of literature. He mocks her. He taunts her. He lists all of her previous mortal lovers and the horrible fates that befell them. “You loved the lion, mighty in strength,” he sneers, “and for him you dug seven and seven pits! You loved the horse, and you decreed for him the whip and the spur! You loved the shepherd, and you turned him into a wolf!” He basically tells her she’s divine poison and he wants no part of it.

Ishtar is, understandably, enraged. Humiliated, she flies up to the heavens and goes straight to her father, Anu, the sky god. “That arrogant Gilgamesh insulted me!” she cries. “Give me the Bull of Heaven to unleash on his city, or I will smash the gates of the underworld and let the dead swarm the earth!”

Anu, terrified of his daughter’s wrath, gives in. The Bull of Heaven, a colossal celestial beast, descends upon Uruk. Its snort opens up cracks in the earth that swallow hundreds of people. It’s a force of total destruction. But this is what Gilgamesh and Enkidu were made for. They fight the Bull together. In a display of perfect teamwork, Enkidu distracts it while Gilgamesh comes in from behind and thrusts his sword into the nape of its neck, killing it.

The city rejoices. But in their moment of triumph, Enkidu commits one final, fatal act of defiance. He rips off the Bull’s thigh and throws it in Ishtar’s face, shouting, “If I could get my hands on you, I would do the same to you!”

That was the last straw. That night, the great gods assemble. They have watched these two mortals slay Humbaba and kill the Bull of Heaven. They have heard Enkidu’s insult. They decide that someone must pay the price. One of the two friends must die. And because Gilgamesh is two-thirds god, they choose Enkidu.

The King Who Feared the Dark

This is where the story pivots. The first half is a rollicking adventure about friendship and glory. The second half is a profound meditation on loss, grief, and the terror of death.

Enkidu falls ill. It’s not a swift, heroic death in battle. It’s a slow, painful, wasting sickness decreed by the gods. He lies in his bed for twelve days, his body failing him. He has terrifying dreams of the underworld, a “house of dust” where the dead sit in darkness, eating clay, and are clothed like birds, with wings. It’s a bleak, grim vision of the afterlife. He curses the trapper who found him and Shamhat who civilized him, blaming them for bringing him out of the wilderness to this fate.

Gilgamesh is beside himself. He sits by his friend’s bed, refusing to leave. He weeps, he rages, he prays. But nothing can stop the inevitable. Enkidu dies.

And Gilgamesh’s grief is monumental. It is one of the most powerful and raw depictions of mourning ever written. He refuses to believe Enkidu is gone. “He touched his heart, but it was not beating.” For six days and seven nights, he refuses to allow the body to be buried, hoping his friend will wake up. He roars like a lioness whose cubs have been taken. He tears at his hair and his fine clothes, covering himself in dust.

“My friend, whom I loved so dearly, who went through all hardships with me—Enkidu, my friend—the fate of mankind has overtaken him… Shall I not die too? Am I not like Enkidu? Grief has entered my heart. I am afraid of death.”

This is the core of the epic. The brash, arrogant king is gone. In his place is a broken man, haunted by the image of his friend’s decay and paralyzed by a new, all-consuming fear: his own mortality. He realizes that his divine blood won’t save him. His strength won’t save him. His fame won’t save him. One day, he too will become dust in a dark house.

He cannot accept it. And so, he embarks on a second quest. This time, he is not searching for glory. He is searching for immortality. He decides to find the one man known to have escaped death: Utnapishtim, the Faraway.

A Journey to the End of the World

Gilgamesh’s new quest is a desperate, solo journey to the very edges of reality. He sheds his royal robes and dons animal skins, a shadow of the man he once was, his face etched with sorrow. He travels to the Mashu mountains, where scorpion-men guard the passage of the sun. They see his despair and, against their better judgment, let him pass into a tunnel of absolute darkness, a path the sun travels at night. For twelve long leagues, he runs through suffocating blackness before emerging, just as the sun rises, into a magical garden where the trees bear jewels as fruit.

Here he meets Siduri, a divine alewife who keeps a tavern by the edge of the sea. She sees this wild, haggard figure and is frightened, barring her door. But Gilgamesh pounds on it and tells her his story. He tells her of Enkidu, and of his crippling fear of death.

Siduri’s response is one of the most beautiful and poignant passages in the epic. It is a dose of simple, profound wisdom. She tells him: “Gilgamesh, where are you wandering? The life that you seek, you will not find. When the gods created mankind, they allotted death to mankind, but life they retained in their own keeping. As for you, Gilgamesh, let your belly be full, make merry day and night. Of each day make a feast of rejoicing. Day and night dance and play! Let your garments be sparkling fresh, your head be washed; bathe in water. Pay heed to the little one holding your hand, let your spouse delight in your bosom. For this is the task of mankind.”

It’s the world’s first “carpe diem.” Seize the day. Stop chasing immortality, she says, and embrace the mortal life you have. Find joy in food, in music, in family, in love. This is the purpose of being human.

But Gilgamesh is not ready to hear it. He is too deep in his grief. He rejects her wisdom and asks how he can cross the Waters of Death to reach Utnapishtim. Siduri directs him to Urshanabi, the ferryman, who, after some convincing, agrees to take him.

The Man Who Survived the Flood

Finally, after his impossible journey, Gilgamesh stands before Utnapishtim. He looks at this legendary figure, the only immortal man, and he’s surprised. Utnapishtim doesn’t look like a god. He looks like an ordinary old man. “I look at you,” Gilgamesh says, “and you’re just like me. How did you get eternal life?”

And so Utnapishtim tells his story. And it’s a story that would have shocked its first modern readers in the 19th century, because it’s a detailed account of a Great Flood, sent by the gods to wipe out humanity. The god Ea, taking pity on Utnapishtim, secretly warns him to build a giant boat, an ark, and to load it with his family and the “seed of all living things.” The rains come, a tempest floods the entire world, and everyone else drowns. When the waters recede, the boat lands on a mountain. Utnapishtim sends out a dove, then a swallow, then a raven, which does not return, signaling that dry land has appeared.

If this sounds familiar, it should. This story, written more than a thousand years before the earliest version of the biblical book of Genesis, is a clear precursor to the story of Noah’s Ark. Its discovery was a bombshell, showing how these ancient tales migrated and evolved across cultures.

After the flood, the god Enlil, who had caused the destruction, feels remorse. As a reward for surviving, he grants Utnapishtim and his wife immortality. “But,” Utnapishtim says to Gilgamesh, “that was a one-time thing. Who will convene the council of the gods for you, so that you can find the life you seek?”

To prove how unfit Gilgamesh is for immortality, Utnapishtim gives him a simple test: “Just try to stay awake for six days and seven nights.” After all, sleep is a little taste of death. If you can’t conquer sleep, how can you conquer death itself? Gilgamesh, exhausted from his journey, sits down… and immediately falls fast asleep.

He sleeps for seven days. To prove it, Utnapishtim’s wife bakes a loaf of bread for each day he sleeps and places it beside him. When he wakes up and denies he’s been asleep, Utnapishtim shows him the loaves in their various states of decay, from fresh to stale to moldy. Gilgamesh is devastated. He has failed the simplest test. He cannot escape his own human nature.

Seeing his despair, Utnapishtim’s wife takes pity on him. She convinces her husband to give Gilgamesh a parting gift. Utnapishtim tells him of a magical plant that grows at the bottom of the ocean, a thorny plant that can restore youth to the old. It’s not immortality, but it’s a second chance at life.

Gilgamesh ties stones to his feet, sinks to the bottom of the sea, and finds the plant. Despite its thorns, he grasps it and brings it to the surface, triumphant. He has not found eternal life, but he has found rejuvenation. His plan is to take it back to Uruk, test it on an old man first, and then use it himself. He begins the long journey home.

One hot day, he stops to bathe in a cool pool of water. He leaves the plant on the bank. And while he is bathing, a snake smells the plant’s fragrance, slithers out, and eats it. As it moves away, the snake sheds its skin, instantly renewed. And Gilgamesh is left with nothing. He sits down and weeps. It’s all gone. The quest, the struggle, the hope. It was all for nothing. The finality of his failure is absolute.

Coming Home: The Walls of Uruk

The end of the epic is quiet, but incredibly powerful. Gilgamesh, empty-handed and finally defeated, returns to his home city of Uruk with the ferryman, Urshanabi. As they approach, he turns to the ferryman and says, “Go up, Urshanabi, walk upon the walls of Uruk. Inspect the foundation platform, and scrutinize the brickwork. Testify that its bricks are baked bricks, and that the Seven Sages laid its foundations!”

This is the end of his journey. He has come full circle. The story began with a description of these same walls, built by a tyrannical king as a monument to his own ego. Now, at the end, Gilgamesh sees them in a new light. He didn’t find personal immortality. The snake stole his chance at rejuvenation. But as he looks at the massive, well-built walls of his city, he understands.

His legacy is not in living forever. His legacy is the city he built, the civilization that will outlive him. It’s in the works of human hands, in the community we create, in the stories we tell. The very tablet on which his story is written is part of that legacy. True immortality isn’t about cheating death; it’s about accepting our mortality and creating something of value within the time we have. The tyrant who took from his people has become a wise king who understands that his greatest creation is for his people. He has finally learned the lesson Siduri tried to teach him. He has accepted the task of mankind.

And so, the first great story in literature is not about achieving godhood. It’s about becoming fully, truly, and wisely human. It’s a 4,000-year-old reminder that our lives are finite, that our friendships are precious, that grief is a measure of our love, and that what we build and leave behind is our only real claim to eternity. The scribes of Mesopotamia didn’t just give us an adventure story; they gave us a blueprint for meaning.

Next time, we leave the dusty plains of Mesopotamia and set sail across the Mediterranean. Our journey takes us to the sun-drenched islands of the Aegean, where a blind poet will sing of the wrath of Achilles, and cunning kings will battle monsters and gods. We’re heading to ancient Greece, to explore the heroic epics and groundbreaking tragedies that would become the foundation of the entire Western world. Join me as we listen for the Echoes of Olympus.

List of Episodes in the Series

The Story of Literature EP1 | The First Scribes: Tales from the Fertile Crescent

The Story of Literature EP2 | Echoes of Olympus: The Greek and Roman Foundations

The Story of Literature EP3 | The Ocean of Stories: Epics and Wisdom of South Asia

The Story of Literature EP4 | The Brush and the Sword: Poetry and Philosophy in East Asia

The Story of Literature EP6 | Forging a Continent: From Beowulf to the Enlightenment

The Story of Literature EP7 | The Soul of the Steppe: The Great Russian Psychological Novel

The Story of Literature EP8 | Magic and Memory: The Boom of Latin American Literature

The Story of Literature EP9 | The Griot’s Legacy: Oral Traditions and Post-Colonial Voices of Africa

The Story of Literature EP10 | The Global Bookshelf: Migration, Identity, and the 21st-Century Story

0 Comments