- Audio Article

- The Empathy Engine: Why Stories Succeed Where Statistics Fail

- Case Study: The Book That Made a War Inevitable

- Case Study: A Literary Bomb Against an Empire

- The Lever in the Modern Age

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language: Vocabulary and Speaking

- Focus on Language: Grammar and Writing

- Vocabulary Quiz

- The Debate

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

Audio Article

It’s a strange thought, isn’t it? In our world of 24/7 news cycles, viral videos, and digital activism that flashes across the globe in seconds, the idea of a book—a physical, static object made of paper and ink—changing the world can feel… quaint. Like something out of a history textbook, filed next to the horse-drawn carriage and the telegram. We’re accustomed to change that feels loud, fast, and fleeting. A book is the opposite. It’s a quiet, slow burn. It asks for hours, sometimes days, of our undivided attention.

And yet.

Archimedes, the ancient Greek brainiac, famously said, “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” For centuries, humanity has searched for such levers in politics, in warfare, in technology. But we’ve consistently overlooked one of the most powerful levers of all: the well-told story. Literature, in its most potent form, is not mere entertainment or escapism. It is a lever for the mind, a fulcrum for the heart. It can take the abstract, distant suffering of millions and give it a human face, a name, and a voice. It can dismantle ideologies, challenge injustice, and galvanize generations to action, proving that the quietest revolutions often begin with the turning of a page. This isn’t just a romantic notion; it’s a historical fact, written in the ink of authors who dared to believe their words could build a better, or at least a more honest, world.

The Empathy Engine: Why Stories Succeed Where Statistics Fail

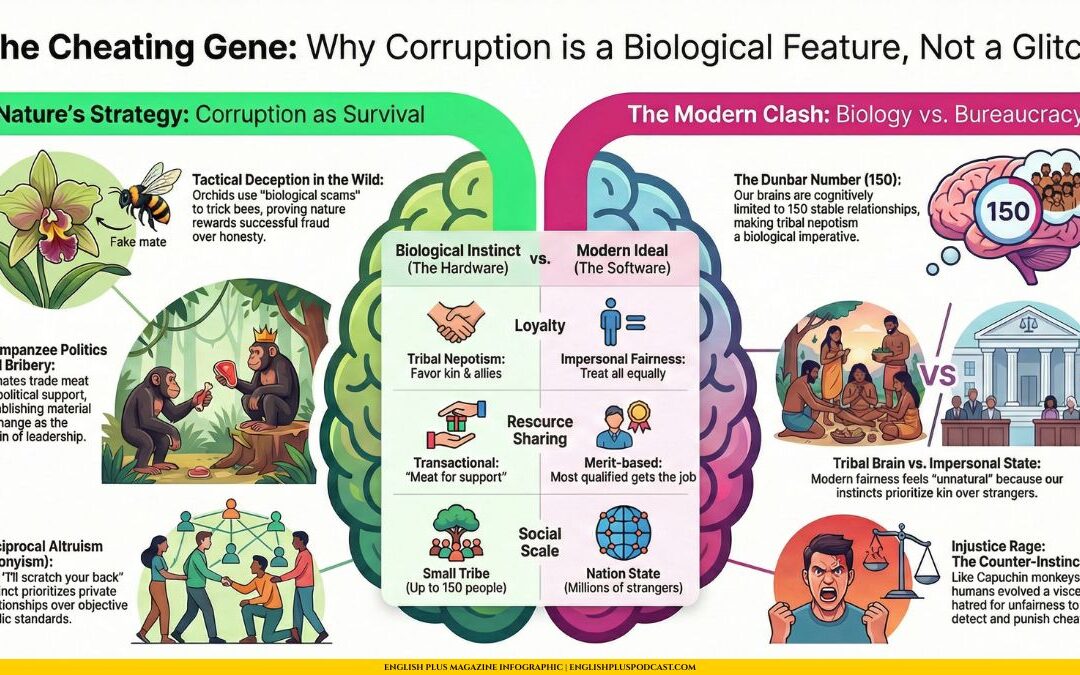

Before we dive into the history-altering case studies, we have to ask a fundamental question: Why? Why does a story work so effectively? You can present someone with a mountain of data about injustice—poverty rates, casualty numbers, incarceration statistics—and their eyes might glaze over. The numbers are too big, too impersonal. They register in the logical part of our brain but fail to connect with the part that feels, the part that drives us to act.

Literature performs a kind of psychological alchemy.

Walking in Another’s Shoes

A novel doesn’t tell you about a person; it puts you inside their head. Through narrative, you’re not just an observer; you’re a participant. You feel the biting cold of a Siberian winter alongside a political prisoner, you experience the suffocating humidity and moral degradation of a slave plantation, you share the quiet desperation of a family losing their farm during the Great Depression. This immersive experience cultivates empathy, a deep, visceral understanding of another’s lived reality. It bypasses our intellectual defenses and speaks directly to our shared humanity. You can argue with a statistic, but it’s much harder to argue with a feeling, with the phantom pain of a fictional character who has, for a few hundred pages, become real to you.

Humanizing the Abstract

Social and political issues are, by their nature, complex and abstract. “Systemic injustice” and “ideological oppression” are important concepts, but they lack a heartbeat. A novelist takes that abstraction and gives it a story. Harriet Beecher Stowe didn’t write a treatise on the economic evils of slavery; she gave us the dignified, suffering Uncle Tom and the fiercely protective mother, Eliza, leaping across a frozen river to save her child. John Steinbeck didn’t write a sociological analysis of the Dust Bowl; he gave us the Joad family, piling their meager belongings onto a sputtering truck, driven by a sliver of hope. These characters become proxies for millions, their individual struggles illuminating a collective tragedy. They transform a political problem into a human one, and human problems demand human solutions.

Case Study: The Book That Made a War Inevitable

If there was ever a single book that could lay claim to starting a war, it’s Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852. To understand its cataclysmic impact, you have to picture the America of the time. It was a nation deeply, venomously divided over slavery, but for many in the North, it was a distant, political issue. They were against it in principle, sure, but it wasn’t part of their daily lives. It was something happening “down there.”

From Parlor Reading to Political Firestorm

Stowe’s novel changed everything. It was published first as a serial in an abolitionist newspaper and then as a two-volume book. Its success was explosive and unprecedented. It became the second-best-selling book of the 19th century, trailing only the Bible. But it wasn’t just a bestseller; it was a cultural phenomenon. It was read aloud in family parlors, adapted into wildly popular (and often wildly inaccurate) stage plays, and discussed, debated, and dissected in every corner of society.

Stowe’s genius was her use of sentimental fiction—a popular genre at the time that focused on domestic life and Christian morality—as a Trojan horse for radical abolitionist politics. She didn’t lecture her readers. She made them weep. She crafted characters like Tom, whose unwavering Christian faith in the face of unspeakable cruelty made him a martyr, and Eliza, whose desperate flight tapped into the universal terror of a parent losing a child. She also painted a brutal, unflinching portrait of the villain Simon Legree, a Northerner-turned-slave-owner, cleverly implicating the North in the sin of the South.

The Unmistakable Aftershocks

The reaction was as divided as the nation itself. In the North, it galvanized the abolitionist movement like nothing before. It moved slavery from the realm of political debate into the realm of a moral and religious crusade. It gave a face to the millions of enslaved people the North had previously ignored, forcing a moral reckoning. For many, reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the first time they truly felt the inhumanity of the institution.

In the South, the book was met with apoplectic rage. It was banned, burned, and furiously denounced as a pack of slanderous lies. A whole genre of “anti-Tom” literature sprang up, attempting to portray slavery as a benevolent, paternalistic system. This furious backlash only served to deepen the chasm between North and South, hardening positions and making compromise impossible.

The famous, though likely apocryphal, story is that when Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1862, he said, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” Whether he actually said it or not is beside the point. The legend persists because it contains a deeper truth: Uncle Tom’s Cabin framed the moral terms of the conflict. It turned the tide of public opinion and helped create the political will necessary for emancipation, proving that a story could indeed be a declaration of war.

Case Study: A Literary Bomb Against an Empire

Fast forward over a century to a different kind of empire, built on a different kind of slavery: the Soviet Union. By the 1970s, many Western intellectuals still clung to a romanticized view of communism, willing to overlook or downplay the regime’s brutalities. The whispers of the Gulag—the vast network of forced labor camps—were there, but they were easy to dismiss as Cold War propaganda.

Then, in 1973, a book detonated in the collective consciousness of the West. It was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.

The Power of Bearing Witness

This wasn’t a novel. It was, as Solzhenitsyn subtitled it, “An Experiment in Literary Investigation.” For years, he had secretly collected the stories of 227 fellow survivors of the camps, weaving their testimonies together with his own experiences into a monumental, three-volume history of Soviet terror. It was a meticulous, crushing, and irrefutable indictment of a system that had consumed millions of lives. The manuscript was smuggled out of the USSR on microfilm and published in Paris.

The Gulag Archipelago is not an easy read. It’s a sprawling, dense, and horrifying catalogue of human cruelty. But its power lies in its authenticity. It’s not fiction; it is truth, weaponized. Solzhenitsyn’s unflinching prose documents everything: the arbitrary arrests in the dead of night, the farcical trials, the brutal interrogations, the cattle cars packed with prisoners, and the slow, grinding death of the camps from starvation, disease, and overwork.

Shattering the Illusion

The impact was seismic, particularly on the European left. For those who had held out hope for the communist experiment, Solzhenitsyn’s work was a point of no return. It was impossible to read The Gulag Archipelago and continue to make excuses for the Soviet Union. The book systematically dismantled the moral and intellectual foundations of Soviet communism, exposing its core not as a flawed utopia, but as a vast, murderous machine. It revealed that the terror wasn’t an aberration of the system under Stalin; it was the system itself, from Lenin onward.

The Soviet authorities, predictably, stripped Solzhenitsyn of his citizenship and exiled him. But the damage was done. The book became a samizdat sensation within the Soviet Union, passed secretly from hand to hand, a testament to the truth that the regime tried so desperately to erase. Globally, it re-framed the Cold War, not just as a geopolitical struggle, but as a moral one. It armed the West with a powerful new understanding of their adversary and gave renewed courage to dissidents behind the Iron Curtain. It was a single author, with a single manuscript, chipping away at the foundations of a superpower.

The Lever in the Modern Age

The world has changed since Stowe and Solzhenitsyn. Our attention spans are shorter, and we are inundated with information. Does the literary lever still have the power to move the world?

The answer is yes, though its function has evolved. Books like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring have had profound impacts on policy and public consciousness regarding mass incarceration and the environmental movement, respectively. They function as slow-release capsules of thought, setting the agenda for years of conversation.

Even fiction continues its subversive work. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, though written in 1985, has found a stunning new life as a cultural touchstone and a symbol for women’s rights protests around the world. The red robes and white bonnets seen at political rallies are a testament to the enduring power of a story to provide the language and iconography for modern resistance.

The delivery method might change—from serialized novels to e-books to audiobooks—but the core mechanism remains the same. A compelling narrative grabs us in a way that a tweet or a headline never can. It demands we slow down, reflect, and, most importantly, feel. In an age of noise, the focused quiet of a book might be more revolutionary than ever. It offers us the space to build empathy, to understand complexity, and to arm ourselves with the most powerful tool for change there is: a new perspective. The pen is not just a lever; it’s a key, unlocking the parts of our own humanity that can, in turn, unlock a better world.

MagTalk Discussion

MagTalk Transcript

Okay, picture this. A stack of paper and ink, right? Just a book. Versus, say, a really slick, fast-cut, viral video.

Yeah, the kind that gets millions of views in, like, an hour. Exactly. So which one? Which one actually changes things? Like, deep down Ben’s history.

It’s a fascinating question, isn’t it? Which one truly sparks, maybe, a moral crusade? Or even builds enough pressure to shake a superpower? Yeah, because we live in this age that just worships speed and noise, you know? We expect change to be loud, immediate, almost flashy. Definitely. And yet, when you look back, history often shows something else.

It does. That the biggest, most world-altering shifts, they often start quietly, with a narrative, a slow brand. And that’s what we’re diving into today, this astonishing power that literature seems to hold.

We’re asking, you know, how can a story, maybe about a family that never existed, or a really detailed, harrowing account of state cruelty, how can that succeed? Right. Succeed where, like, mountains of statistics, cold, hard data, just fail. They don’t even seem to register sometimes.

We want to explore the psychology behind why stories are so potent, and look at some solid historical proof. Basically, how stories can be the ultimate tool for change. Welcome to a new MagTalk from English Plus podcast.

Okay, so let’s unpack this a bit. We’re looking at literature, but not just as entertainment. We’re exploring this idea of literature as, well, almost like Archimedes’ lever.

That famous idea, yeah. Give me a lever long enough, a place to stand, that I can move the world. Exactly.

And the argument here is that this lever, the one that can really move the world by changing hearts and minds first, well, might just be literature. It’s a powerful metaphor. So we’ll explore the why, the psychological reasons stories grip us so tightly.

And then we’ll get into the how, with two huge case studies. First, a novel that arguably helped make the American Civil War unavoidable. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a massive one.

And second, an investigation, a piece of nonfiction that essentially broke the moral back of the Soviet Empire. Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, another incredibly powerful example. So yeah, a deep dive into books that didn’t just reflect the world, they actively shaped it.

So let’s start with this apparent contradiction. In our world, our 24-7 news cycle, digital activism, everything instant. The idea of a book, a physical, static thing, changing the world feels almost quaint.

Yeah, almost old fashioned. Right. We look for change in, I don’t know, disruptive tech, mass movements online, political shifts.

Things that are loud and fast. That’s what we’re conditioned to expect now. Literature is the opposite.

It’s quiet, it’s slow, it demands focus, sustained attention. Which is a rare commodity these days. Absolutely.

But maybe that quietness, that demand for attention is actually where its strength lies. That Archimedes quote you mentioned, give me a lever long enough. We’re always searching for that lever, aren’t we? In politics and technology and economics.

Billions spent looking for the next big thing that will shift everything. But maybe we consistently overlook this incredibly powerful tool that’s been right there all along, the well-told story. I think that’s exactly right.

Literature in this context isn’t just escapism. It’s not just art for art’s sake, though it can be that too. It’s this overlooked lever for the mind.

And the fulcrum, the place you put the lever. That’s the human heart, the emotional core. It performs this kind of cognitive function that technology just can’t replicate.

It turns abstract suffering, numbers on a page, into a human face, a voice, a name. So it makes it real in a way data doesn’t. Precisely.

And that reality, that felt experience, is what can galvanize people, sometimes across generations. Think about it. A policy paper might influence a few experts, maybe shape a law.

A powerful story can embed itself in the cultural consciousness for decades. It has that slow burn effect you mentioned. It takes time to read, to digest, to reflect.

It demands hours of mental space. And during those hours, something profound can happen. It’s not just information transfer.

While, say, a statistical report tries to convince your logical brain. Your analytical side, yeah. A novel or a powerful narrative nonfiction, it seeks to transform your experiential reality.

It doesn’t just aim for the head. It aims right for the core of who you are. So it’s less about convincing and more about inhabiting.

Exactly. Inhabiting another perspective, another life. And that transformation, that shift in perspective, felt deep down that’s incredibly robust.

It sticks with you in a way a fleeting headline or a viral clip rarely does. It’s resistant to what you called cognitive decay. I like that.

Yeah. The memory of a powerful feeling, an empathic connection, decays much slower than a list of facts. So the quietest revolutions might really start with someone, somewhere, just turning a page.

And that experience then ripples outwards. It gives a name and a face to distant problems. And that’s the first step towards demanding change.

You have to feel the need for it first. OK, so before we jump into the big historical examples like Stowe or Solzhenitsyn, we really need to nail down why. What’s the psychological mechanism here? Why is this literary lever so much better at, say, motivating action than just pure data? Yeah, that’s the absolute core question, isn’t it? Because logically, we live in the information age.

If just knowing facts was enough to fix things. We’d live in a perfect world. Right.

We’d have solved everything by now. But you present someone with, like you said, a mountain of data, poverty stats, casualty numbers, incarceration rates. What often happens? Eyes glaze over.

It’s too much. It’s impersonal. Psychologists even have a term for it.

Compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue. OK.

Yeah. When the numbers get too big or the problem feels too abstract and distant, our emotional circuits kind of short out. They don’t engage.

The logical brain might file the data away. OK, noted. That’s bad.

Yeah. But the part that actually feels something, the part that drives empathy and motivates us to, you know, stand up and do something, that part stays quiet. It’s like the scale numbs us.

The suffering of one person can feel unbearable. But the suffering of a million becomes a statistic. Precisely.

It’s an abstraction. You can intellectually understand that millions are suffering. You can even memorize the stats for a test.

But that intellectual grasp rarely translates into genuine political will or, you know, personal sacrifice. You need that emotional trigger. That gut punch.

And that is exactly what literature provides. It performs this kind of, well, it feels like psychological alchemy almost. It’s called narrative transportation.

Narrative transportation. OK. It’s a recognized psychological phenomenon.

When a story is really immersive, when it pulls you in completely, your critical thinking, your intellectual defenses, they kind of lower. You stop analyzing the text from the outside. And you start.

You start experiencing the world the text creates. You’re not just an observer watching a character. For that moment, you almost become that character.

You’re transported into their reality. So it’s immersive participation, not just detached observation. Exactly.

A good writer doesn’t just tell you the prisoner was cold. They make you feel that biting Siberian cold. They describe the ice forming inside the windowpane, the way the thin blanket does nothing, the gnawing ache in your bones.

Or the feeling on a slave plantation. Not just the injustice, but the daily fear, the moral compromises, the crushing weight of it all. Or think about the Jode family in The Grapes of Wrath.

You don’t just read about the Dust Bowl. You share their quiet, gnawing desperation as they load up that broken down truck. That truck becomes your last hope, too, for those pages.

So that immersion, that’s what builds the empathy. That deep, visceral connection. Yes.

Visceral is the right word. Sometimes it’s painful empathy. And the power of that is, well, think about it.

You can argue with a statistic all day long, right? Oh, yeah. Challenge the methodology, debate the interpretation, find conflicting data. Exactly.

But how do you argue with a feeling? How do you argue with the phantom pain, as you put it, of a character who has become intensely real to you? It’s almost impossible. The story slips past your ideological defenses and speaks directly to your shared humanity. That’s the real genius, then.

Humanizing the abstract. Issues like systemic injustice or economic inequality, they’re huge, important concepts, but they don’t have a heartbeat. Novelists provide the heartbeat.

They take these massive, complex problems and distill them into individual human experiences. Like you said, Harriet Beecher Stowe didn’t write a dense report on the economics of slavery. No.

She gave us Uncle Tom, this devout man facing unimaginable cruelty. She gave us Eliza, the mother terrified for her child. Specific people.

And Steinbeck didn’t give us charts on soil erosion and foreclosure rates. He gave us the Joads. Packing that old truck, heading west on a whisper of hope.

These characters, Tom, Eliza, the Joads, they become proxies for millions. They transform a political or economic problem into a human problem. And human problems demand human solutions.

Once you’re emotionally invested in Tom’s fate or the Joads’ survival, you can’t just shrug and say, well, it’s complex. You feel the urgency. You demand action.

Okay, so as we’re talking about literature as a world-moving lever, we absolutely have to spend some time on Uncle Tom’s cabin. Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1852. It’s probably the most dramatic American example.

Oh, absolutely. Its impact was seismic. Many historians argue it didn’t just reflect the tensions leading up to the Civil War.

It actively inflamed them. It helped make the conflict inevitable. So set the scene for us.

1852, America. Right. The country was already deeply, venomously divided over slavery.

But importantly, after the Compromise of 1850, which included the really harsh Fugitive Slave Act. Which forced Northerners to participate in returning escaped slaves. Exactly.

There was a kind of exhaustion, especially in the North. Many people opposed slavery in principle, sure, but they wanted it to remain a distant issue. A political problem happening down there in the South.

They didn’t want to confront its brutal reality daily. And then comes Stowe’s novel. First published as a serial in an abolitionist newspaper, right? Yes.

Then as a two-volume book. And it just exploded. Nothing like it had been seen before, really.

Hundreds of thousands of copies sold within the first year. It became the second best-selling book of the entire 19th century. Second only to the Bible.

Second only to the Bible. That gives you a sense of the scale. It wasn’t just a bestseller, it was a full-blown cultural phenomenon.

How did that manifest? How did people interact with it? It was everywhere. People read it aloud in their homes, in parlors. Families would gather to hear the next installment.

It was discussed constantly, debated fiercely. And maybe most significantly, it was adapted into these incredibly popular stage plays, the Tom Shows. Ah, the Tom Shows.

Often quite melodramatic and not always faithful to the book, I gather. Often wildly inaccurate, yes. But hugely popular.

They brought the characters and the emotional core of the story to vast audiences who might not have even read the book. The point is, it became impossible for anyone in America, North or South, to ignore the moral questions the book forced onto the table. So let’s talk about Stowe’s strategy here.

Because it wasn’t just a raw outpouring of emotion, it was strategically brilliant. She wasn’t writing for academics or politicians primarily. No, absolutely not.

She tapped into the most popular literary genre of the time, sentimental fiction. Think novels focused on domestic life, family, Christian piety, intense emotions. Stuff that was primarily read by women, by the middle class.

Exactly. And she used that familiar, popular form as a kind of Trojan horse to deliver a radical abolitionist message. Clever.

So she wasn’t trying to win arguments with logic. Her goal wasn’t to lecture people on economics or constitutional law. Her explicit goal was to make her readers feel, to make them weep.

She targeted the heart, not the head. How did she do that? Through the characters mainly. Primarily.

By focusing relentlessly on the destruction of the family, enslaved families being torn apart, mothers separated from children, husbands from wives. She struck directly at the core values of her 19th century readers. For her white, Christian, Northern audience, the family was sacred.

She forced them to see that enslaved people felt that same sacred bond and that slavery systematically destroyed it. And the specific characters were key. Uncle Tom himself.

Tom is constructed as a kind of Christian martyr. Yeah. Deeply pious, forgiving, almost Christ-like in his suffering, his unwavering faith in the face of escalating horrifying cruelty from different owners that resonated powerfully with the religious readership.

His suffering wasn’t just political. It was framed as a profound moral and spiritual trial. And then Eliza.

Eliza’s flight across the frozen Ohio river, clutching her child, escaping the slave catchers that tapped into something universal, the primal terror of a parent desperate to save their child. You don’t need complex arguments about property rights to feel the power of that scene. It’s instant visceral empathy.

Who wouldn’t root for Eliza? You can’t argue with that image. Impossible. And then there’s the villain, Simon Legree.

Stowe made a very deliberate choice there. He wasn’t a Southern gentleman planter, was he? No. Crucially, Legree is depicted as a Northerner, a tranplant who moved south explicitly to make money through brutal exploitation.

Ah, so that implicated the North too. Precisely. It was a strategic masterstroke.

It prevented Northern readers from feeling morally superior, from thinking slavery was just a Southern sin. It suggested the greed and cruelty driving slavery had roots everywhere. Even in the supposedly free North, the whole nation was complicit.

Okay, so the book explodes. What were the immediate aftershocks? How did it actually shift things? In the North, the impact was transformative. It didn’t just give the existing abolitionist movement more supporters.

It fundamentally changed the nature of the movement. It shifted the debate decisively from politics and law towards morality and religion. It became a crusade.

So it wasn’t just about policy anymore. It was about saving souls, the soul of the nation. In many ways, yes.

For millions of Northerners who had previously been ambivalent or just vaguely uncomfortable, reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the first time they truly felt the absolute inhumanity of slavery. It forged the moral outrage and the political will that would eventually be necessary for war and emancipation. And the reaction in the South.

Predictable, I guess. Truly apoplectic rage. The book was denounced as vicious slander, full of lies.

It was banned, burned in public bonfires. Southern leaders and newspapers were furious at this portrayal. And that led to that weird literary counter-reaction you mentioned.

Yes, the anti-Tom novels. Recognizing the incredible power of Stowe’s narrative, Southern writers rushed out their own novels trying to counteract it. What were they like? They typically portrayed slavery as this benevolent, paternalistic system.

Happy, singing enslaved people, kindly masters, often contrasting the supposed Southern idol with the harsh industrial factories and wage slavery of the North. Titles like Aunt Phyllis’ Cabin, or Southern Life as it is, or The Planter’s Northern Bride. Trying to fight fire with fire, using literature as their own lever.

Exactly. But the very fact that they felt compelled to write these defensive fantasies just proved how devastatingly effective Stowe’s book had been. It had seized the moral narrative.

So ultimately the book deepened the divide. Massively. The furious Southern backlash.

The North’s embrace of the book as moral truth. It just hardened positions on both sides. It made any kind of compromise seem impossible, even immoral.

Which brings us back to that maybe apocryphal Lincoln quote, meeting Stowe and saying, so you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war. Right. Whether he actually said it or not is debated by historians.

But the reason the story persists is because it captures a deeper truth. Uncle Tom’s Cabin didn’t fire the first shot at Fort Sumter, obviously, but it framed the moral terms of the conflict. It created the widespread emotional and political will in the North to fight for emancipation.

It moved the heart of a nation, and in doing so, it moved the world. Okay, let’s jump forward now over a century later. Different context, different kind of book, but arguably an even more direct assault on the foundations of an empire.

We’re talking about Aleksandr Soltanitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Right. Published in the West, starting in 1973.

And the context here in the early 70s is really important to grasp too. Absolutely crucial. Because despite decades of evidence of Soviet repression, there was still this lingering, well, romanticism maybe.

Especially among some intellectuals in left-leaning circles in the West. Exactly. There was a tendency to downplay or dismiss reports of brutality, particularly the scale and nature of the Gulag, the vast network of forced labor camps, as just, you know, Cold War propaganda.

Exaggerations by the West. And Soltanitsyn’s book just shattered that illusion. It detonated it.

The book, which he subtitled An Experiment in Literary Investigation, wasn’t written in secret, compiled over years, hidden piece by piece, and finally smuggled out of the Soviet Union on microfilm. Its publication in Paris in 73 was like a bomb going off in the intellectual and political landscape of the West. And this was a totally different beast from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, right? This wasn’t sentimental fiction aiming for tears.

Not at all. This was truth as a weapon. Meticulously researched, documented fact, presented with literary power, yes.

But its primary aim was devastating, irrefutable exposure. How would he compile it? It’s massive. Three volumes.

It was an incredible, dangerous undertaking. Soltanitsyn himself was a survivor of the camps. He’d spent years imprisoned.

He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, largely for earlier works about the camps. But he knew his own experience wasn’t enough to counter the Soviet state’s denials. So he needed more evidence.

He needed an avalanche of evidence. Over many years, secretly, risking arrest for himself and everyone involved, he collected the testimonies of 227 other survivors. Zeks, as they were called.

He wove their stories together with his own experiences, historical analysis, Soviet documents, creating this crushing, undeniable mosaic of the entire system. And the detail. It’s famously relentless, isn’t it? Relentless is the word.

It’s dense. It’s sprawling. It’s horrifying.

It documents everything. The arbitrary midnight arrest, the knock on the door that everyone feared. The absurd farcical trials based on nothing.

The brutal interrogations using torture and sleep deprivation to get meaningless confessions. The journey to the camps. The infamous cattle cars packed so tight people suffocated.

And then life. Or rather, slow death. In the camps themselves.

The starvation rations. The rampant disease. The killing labor in freezing mines or logging sites.

The casual brutality of the guards. It’s all there, documented in painstaking, soul-crushing detail. But it wasn’t just a catalog of horrors, was it? It had a central argument.

That’s what made it so devastating, particularly for those in the West who still held out hope for communism. Solzhenitsyn’s core argument, backed by this mountain of evidence, was that the gulag, the mass terror, wasn’t some unfortunate mistake or an aberration that only happened under Stalin. Not just a personality cult gone wrong.

Exactly. He argued, convincingly, that the terror was inherent in the system from the very beginning. He traced its roots back to Lenin and the Red Terror right after the revolution.

He showed how the ideology and the bureaucratic structures of the Soviet state required this kind of mass repression to maintain control. So it wasn’t a bug. It was a feature.

Precisely. He demonstrated that the core of the Soviet project wasn’t a flawed utopia, but a vast bureaucratic machine built on fear and designed for mass murder. This completely dismantled the moral foundations of Soviet communism for anyone willing to look honestly at the evidence.

For many on the European left especially, reading gulag was the point of no return. It killed the dream. How did the Soviet authorities react? They must have been terrified.

They were furious and terrified. Solzhenitsyn was already a thorn in their side, but this was orders of magnitude worse. Shortly after the first volume was published in the West, They arrested him, formally charged him with treason, stripped him of his Soviet citizenship, and forcibly exiled him.

Put him on a plane to West Germany. But they couldn’t put the book back in the bottle. No way.

The damage was done. The truth was out and it was circulating globally. And internally within the USSR, the book became a legend of Semizdat.

Semizdat, the underground self-publishing network. Yes. People would secretly type out copies, often making multiple carbons, risking years in the gulag themselves if caught.

These flimsy typed manuscripts would be passed secretly from hand to hand, read intensely, hidden. It wasn’t just a book. It was an act of defiance, a testament to the truth the regime was trying to erase.

It gave people courage. And the impact globally, beyond disillusioning Western intellectuals. It fundamentally reframed the Cold War.

It stripped away a lot of the ideological ambiguity. For many people, it was no longer just about competing economic systems or geopolitical influence. It became a clearer moral struggle.

Democratic freedoms versus a totalitarian system now exposed in its full horrifying reality. So it armed the West, intellectually and morally. It did.

It gave Western governments and populations a much deeper, more visceral understanding of the nature of their adversary. And perhaps just as importantly, it gave immense courage and validation to dissidents fighting for human rights behind the Iron Curtain. They knew the truth was known.

It’s incredible. One person, one massive book smuggled out on microfilm. And it delivers this devastating blow to the moral legitimacy of a superpower.

It chipped away at those ideological foundations until eventually they crumbled. If that’s not literature acting as a lever to move the world, I don’t know what is. Okay, those are two incredibly powerful historical examples.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The Gulag Archipelago. Books that undeniably changed the course of history.

But we have to ask the question for today, for our world. Does that literary lever still work? It’s the elephant in the room, isn’t it? In this age of TikTok and Twitter and constant information bombardment, shrinking attention spans, does a book still have that kind of power? Can a slow, quiet medium compete with the instant noisy visual onslaught? Seems like a tough ask. It’s a totally valid challenge.

The idea of someone sitting down for, say, the 50 plus hours it might take to read the Gulag Archipelago, it feels less common, perhaps. The demands on our attention are just relentless. So has the lever lost its force? I don’t think so.

I think the answer is still, yes, it works. But maybe the way it works, its function, has evolved a bit to fit the modern landscape. How so? What does that look like now? Well, we still see the power of nonfiction, particularly in setting the long-term agenda.

Think about books that act as these slow-release capsules of thought. Slow-release capsules. I like that.

Give me an example. OK, think about Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring back in 1962. That book didn’t just sell copies.

It essentially launched the modern environmental movement. It forced a national conversation about pesticides, led to policy changes like the banning of DDT. Its impact is still felt today, over 60 years later.

It provided the framework. Right, it set the terms of the debate for decades. Exactly.

Or a more recent example, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, published in 2010. Huge impact on the conversation around mass incarceration in the U.S. Absolutely massive. It fundamentally shifted public understanding and shaped the policy debate for years.

It gave activists, scholars and politicians the language and the analytical framework to understand racial disparities in the justice system. These books don’t just flare up and disappear. They become foundational texts.

They provide the intellectual and moral ballast for sustained movements. So nonfiction can still lay down those deep tracks for future change. What about fiction? Does it still have that subversive power? I think it absolutely does.

But sometimes its leverage works in slightly different ways now. Look at Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Written way back in 1985.

Right. But look at the second life it’s had in recent years. It’s become this potent symbol.

You mean the costumes. The red robes and the white bonnets. Exactly.

When you see protesters wearing those outfits at political rallies, often protesting threats to women’s rights, that’s literature providing the iconography for modern resistance. That’s fascinating. The image itself carries the weight of the story’s themes.

Precisely. You don’t even need to have read the book recently or maybe ever to understand what that visual represents. It instantly communicates a whole complex set of fears and arguments about bodily autonomy, state control, theocracy, misogyny.

A fictional story from decades ago has given modern activists this shared, instantly recognizable visual shorthand. That’s powerful leverage in a visually saturated age. So the core mechanism that narrative transportation we talked about, it still works, even if the delivery method changes.

I believe so. Whether you’re reading a physical book, an e-book on a tablet, or listening to an audiobook, the fundamental power of a compelling narrative to grab you, to pull you into another reality, remains. It forces a different kind of engagement than scrolling through headlines or watching short clips.

It demands more. It forces you to slow down. It forces you to slow down to reflect and, crucially, as we keep saying, to feel.

And maybe, just maybe, in our current age, which is so defined by noise, speed, and overwhelming stimuli, maybe that focused quiet required to really engage with a book is more revolutionary than ever. Like an antidote. Perhaps.

It offers that increasingly rare space to build genuine empathy, to grapple with complexity, and to arm ourselves with the most powerful tool we have for driving real, lasting change. A new perspective. A perspective that we’ve not just learned, but deeply felt.

That’s the enduring power of the literary lever. Okay, so wrapping this up, what’s the big takeaway here for you listening right now? If we look at the lessons from history, from Stowe’s parlor readings to Solzhenitsyn’s smuggled manuscript, it seems clear the pen isn’t just a lever. It’s maybe more like a key.

A key. I like that. A key to what? A key that unlocks those parts of our shared humanity, empathy, moral understanding, the ability to see the world through someone else’s eyes.

And unlocking that, well, that seems essential if we want to unlock a better, more informed world. That makes sense. So the call to action, maybe, is to be really intentional about the stories we let into our lives.

To recognize that consuming a narrative isn’t just passive entertainment, it’s potentially an act of perspective shifting. And to remember that big changes don’t always happen overnight with a viral bang. Sometimes the most profound shifts start quietly, slowly, when someone sits down with a book and allows that narrative alchemy to happen.

So maybe a final thought to leave people with. If we accept this premise that literature often frames our biggest moral challenges before they become mainstream crises, what quiet, maybe unassuming book published recently, one that’s perhaps flying under the radar right now, what story might be shaping the moral or political landscape of the next decade as we speak? That’s a great question to ponder. And this was another MAG Talk from English Plus Podcast.

Don’t forget to check out the full article on our website, englishpluspodcast.com, for more details, including the Focus on Language section and the Activity section. Thank you for listening. Stay curious and never stop learning.

We’ll see you next time.

Focus on Language: Vocabulary and Speaking

Alright, let’s talk about some of the language we used in that article. Words aren’t just tools to get a point across; they’re like paint on a palette. The right ones can turn a simple sketch of an idea into a rich, vibrant painting. Let’s pull apart a few of the more interesting words and phrases we used and see how you can fold them into your own conversations to make your English more precise and powerful.

First up is the word catalyst. In the article, I said literature can be a “catalyst for social and political change.” A catalyst, in chemistry, is something that speeds up a chemical reaction without being used up itself. In everyday language, it’s that person, event, or thing that sparks a major change or action. It’s the trigger. Think about the Arab Spring. The self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia was the tragic catalyst for a wave of protests across the Middle East. It wasn’t the sole cause—the frustrations were already there, simmering under the surface—but his act was the spark that ignited the whole thing. You can use this in so many ways. “Her passionate speech was the catalyst for the team’s comeback in the second half.” Or, “For many people, the pandemic was a catalyst for re-evaluating their careers.” It’s a fantastic word for when you want to talk about the starting point of a big change.

Next, let’s look at galvanize. I wrote that Uncle Tom’s Cabin “galvanized the abolitionist movement.” To galvanize means to shock or excite someone into taking action. It has a sense of electricity to it, like a jolt of energy. It’s stronger than just “motivate” or “inspire.” It implies a sudden, powerful surge of activity where there might have been complacency before. Imagine a community that’s been passively complaining about a dangerous intersection for years. Then, a child is nearly hit by a car. That near-tragedy could galvanize the parents into forming a committee, petitioning the city council, and protesting until a stoplight is installed. You could say, “The company’s terrible environmental report galvanized activists into organizing a boycott.” It’s about being jolted into purposeful action.

Let’s talk about insidious. It’s such a wonderfully sinister-sounding word, and for good reason. I didn’t use this one directly in the final text, but it’s a perfect word to describe the kind of problems literature often tackles. Insidious means proceeding in a gradual, subtle way, but with harmful effects. It’s not a sudden, obvious attack; it’s the kind of danger that creeps up on you. Think of a disease that shows no symptoms for years while slowly damaging your body. That’s an insidious illness. Or think about systemic racism—it’s not always overt, like someone shouting a slur. It’s often insidious, woven into the fabric of institutions in ways that are hard to see but create deeply unequal outcomes. You could say, “The insidious spread of misinformation online is a threat to democracy,” or “He had an insidious way of undermining his colleagues’ confidence with faint praise.” It describes a hidden, creeping evil.

Now for a word that’s its opposite in many ways: unflinching. We described Solzhenitsyn’s writing as “unflinching prose” and his portrait of Simon Legree as “brutal, unflinching.” To be unflinching is to be strong and determined even in a difficult or dangerous situation; it means not flinching, not looking away. It implies courage and a refusal to soften the hard truths. A journalist who reports from a war zone, showing the true costs of conflict without sugarcoating it, is giving an unflinching account. A doctor who has to give a patient a terrible diagnosis must do so with unflinching honesty and compassion. When you’re describing someone who faces reality head-on, no matter how ugly it is, “unflinching” is the word you want. “She gave an unflinching testimony in court, detailing every moment of the crime.”

Let’s grab a great German loanword: zeitgeist. It literally means “spirit of the age” or “spirit of the time.” I didn’t use it in the article, but it’s essential for this topic. The zeitgeist is the general mood, the intellectual, moral, and cultural climate of an era. Some books perfectly capture the zeitgeist of their time, while others help to create it. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is said to perfectly capture the zeitgeist of the Roaring Twenties in America—the glamour, the excess, the moral decay. You could argue that books like The Handmaid’s Tale are now part of the current political zeitgeist. Using it in conversation makes you sound incredibly sharp. “That movie, with its themes of technological anxiety and loneliness, really taps into the current zeitgeist.” Or, “His fashion designs were innovative, but they just didn’t fit the conservative zeitgeist of the 1950s.”

How about visceral? I said literature creates a “deep, visceral understanding.” Visceral relates to deep inward feelings rather than to the intellect. If a reaction is visceral, it’s a gut feeling. It’s not something you thought about and concluded; it’s something you feel in your bones, in your stomach. The horror you feel watching a scary movie is a visceral reaction. The joy a parent feels seeing their child take their first steps is visceral. It’s instinctual and deep. In the context of the article, it means a book doesn’t just make you think slavery is wrong, it makes you feel the horror of it in your gut. You can say, “The politician’s speech provoked a visceral reaction of anger from the crowd,” or “Despite all the logical reasons to sell the house, I had a visceral attachment to it and couldn’t let it go.”

Let’s look at the word quaint. I used it in the beginning to describe how the idea of a book changing the world might seem. Quaint means attractively unusual or old-fashioned. It often has a slightly condescending tone, as if you’re talking about something that’s cute but ultimately irrelevant or outdated. A small village with cobblestone streets and thatched-roof cottages could be described as quaint. The tradition of writing letters by hand might seem quaint in the age of email. So when I say the idea feels “quaint,” I’m acknowledging that in our fast-paced world, it seems like a charming but obsolete concept from a bygone era—before proving that it’s anything but.

Another fantastic word is subversive. I mentioned that even fiction continues its “subversive work.” To be subversive is to seek or intend to subvert an established system or institution. It’s about undermining authority or challenging the status quo from within, often in a clever or secret way. A political cartoon that cleverly mocks a dictator is a subversive piece of art. A piece of music with hidden anti-government lyrics is subversive. Literature is often subversive because it can introduce new, challenging ideas to a society in the seemingly harmless package of a story. A book that questions traditional gender roles or critiques capitalism, even if it’s set in a fantasy world, is doing subversive work. You might say, “Her comedy was deeply subversive, challenging the audience’s assumptions under the guise of jokes.”

Let’s talk about indelible. When a book changes you, it leaves an indelible mark. Indelible means not able to be forgotten or removed. It literally refers to ink that cannot be erased, but we use it metaphorically for experiences and memories that are permanent. The memories of your first love might be indelible. A traumatic event can leave an indelible scar on one’s psyche. A great teacher can have an indelible impact on their students. It speaks to a profound and lasting influence. “The week he spent volunteering at the refugee camp left an indelible impression on him, changing his career path forever.” It’s a powerful way to say “unforgettable.”

Finally, the word dismantle. The article states that literature can “dismantle ideologies” and that The Gulag Archipelago “systematically dismantled the moral and intellectual foundations of Soviet communism.” To dismantle something is to take it apart piece by piece. You can dismantle a machine or a piece of furniture. When you use it metaphorically, you’re talking about taking apart an idea, an argument, or a system to show how it’s constructed and, in doing so, destroying its power. A good debater will dismantle their opponent’s argument, showing the flaws in their logic one by one. Activists work to dismantle systems of oppression. Solzhenitsyn’s book didn’t just say “communism is bad”; it took the entire ideology apart, piece by bloody piece, and showed the horror at its core. It’s a very active, potent word for deconstruction and destruction. “The new documentary aims to dismantle the myths surrounding the diet industry.”

There you have it. Catalyst, galvanize, insidious, unflinching, zeitgeist, visceral, quaint, subversive, indelible, and dismantle. Try to pepper these into your conversations. They’ll add depth, precision, and a bit of flair to your English.

Now, let’s turn this into a speaking lesson. One of the most powerful speaking skills you can develop, directly related to our topic, is the art of persuasive storytelling. It’s not about arguing with facts and figures; it’s about making someone feel your point of view, just like the authors we discussed. The structure is simple: Hook, Emotion, Message.

First, the Hook. You need to grab your listener’s attention immediately. Start with a surprising question or a bold statement. Instead of saying, “I want to talk about the importance of recycling,” try something like, “What if I told you there’s a mountain twice the size of Texas floating in the ocean, and we all helped build it?” That’s a hook.

Second, the Emotion. This is the core. Tell a short, personal story or a vivid anecdote. Don’t just list facts about plastic waste. Describe one specific animal, a sea turtle, mistaking a plastic bag for a jellyfish. Describe its struggle. Use sensory details. Make it visceral. This is where you create that indelible image in your listener’s mind. You need to be unflinching in your description of the problem. Your goal is to make them feel something—sadness, anger, responsibility.

Third, the Message. Once you’ve established that emotional connection, you deliver your point. This is where you connect the story to the larger issue and suggest a course of action. “That turtle is just one of millions. And the insidious problem of plastic pollution won’t go away on its own. We need a fundamental change.” Your story becomes the catalyst for your message.

So, here’s your challenge. I want you to think of a small change you believe in. It could be something in your community, your workplace, or just your family. I want you to prepare a one-minute persuasive story about it. Your goal is to galvanize at least one person into seeing your point of view. Try to use at least three of the words we discussed today: catalyst, galvanize, insidious, unflinching, visceral, indelible, or dismantle. Record yourself giving the one-minute speech. Listen back. Does it have a hook? Does it create emotion? Is the message clear? This is how you move beyond just speaking English to using it as a lever to change minds.

Focus on Language: Grammar and Writing

Let’s transition from the grand scale of world-changing literature to something more personal but equally powerful: your own writing. We’ve talked at length about how narrative can be a more effective tool for persuasion than cold, hard facts. Now, it’s your turn to wield that tool.

Here is your writing challenge:

The Challenge: The Narrative Op-Ed

Write a short persuasive piece, between 700 and 1000 words, in the style of an opinion-editorial (op-ed) or a personal blog post. Your topic should be a social or community issue you care deeply about. It could be anything from mental health stigma, animal welfare, local environmental concerns, to the importance of public libraries.

Here’s the crucial constraint: Your primary method of persuasion must be narrative. While you can include a fact or two, at least 80% of your piece must be dedicated to telling a story—either a true personal anecdote or a compelling fictional vignette—that illustrates the heart of the issue. Your goal is not to lecture or preach, but to create an empathetic connection with your reader that leads them to share your perspective. You are aiming to write a piece that doesn’t just inform, but leaves an indelible mark.

Now, that might sound daunting, but it’s really about shifting your mindset from that of a debater to that of a storyteller. Let’s break down how you can succeed, focusing on some specific writing techniques and grammar points that will elevate your narrative.

Tip 1: The Power of the Specific (Show, Don’t Tell)

This is the oldest rule in the writing handbook, and for good reason. “Telling” is abstract and easy to ignore. “Showing” is concrete and impossible to forget.

- Telling: “Loneliness among the elderly is a serious problem. Many feel isolated and forgotten, which negatively impacts their health.” (Correct, but boring.)

- Showing: “Mr. Henderson’s Tuesday was a map of quiet rituals. He’d watch the dust motes dance in the sunbeam that hit his armchair at precisely 10:17 AM. He knew this because the grandfather clock in the hall, his only companion whose voice never wavered, told him so. Lunch was a single slice of toast, eaten over the sink. He hadn’t spoken a word aloud since the mailman said ‘Have a good one’ yesterday morning. Sometimes, he’d pick up the phone, his thumb hovering over his daughter’s number, before setting it down again. He didn’t want to be a bother.”

See the difference? The first is a statistic you’d forget. The second is a person you worry about. To achieve this, focus on sensory details. What does the scene smell like? What sounds are there (or what is the sound of the silence)? What is the texture of the armchair fabric? Ground your reader in a physical, tangible reality.

Tip 2: The Grammar of Immediacy – Active Voice and Strong Verbs

To make your story feel alive and urgent, you need to use language that is direct and impactful. The biggest tool in your arsenal here is the active voice.

- Passive Voice: “The ball was hit by the boy.” (The sentence is passive, lifeless. The subject, the ball, is being acted upon.)

- Active Voice: “The boy hit the ball.” (The subject, the boy, is performing the action. It’s direct, clear, and has more energy.)

When you’re telling a story, especially a persuasive one, you want your characters to be agents, to be doing things. Scour your draft for passive constructions (often using forms of “to be” + a past participle, like “was told,” “were seen,” “is considered”). In most cases, you can flip them into stronger, active sentences.

Combine this with a hunt for weak verbs. Verbs are the engine of your sentences. Don’t weigh them down with adverbs. Instead of “walked slowly,” try “ambled,” “shuffled,” or “trudged.” Instead of “said loudly,” try “shouted,” “bellowed,” or “declared.” Each of these verbs carries its own emotional weight and paints a more specific picture.

Grammar Deep Dive: The Subjunctive Mood for Persuasion

Okay, let’s get into some more advanced grammar that is tailor-made for this kind of persuasive, hypothetical writing. The subjunctive mood might sound intimidating, but it’s a subtle tool for talking about things that aren’t quite real: wishes, suggestions, hypotheticals, or commands. It’s perfect for gently guiding your reader toward a desired outcome.

The subjunctive often feels a little “wrong” to modern ears, which is why it stands out. The most common form you’ll encounter is with the verb “to be,” which becomes “were” for all subjects.

- Indicative (states a fact): “He was the one in charge.”

- Subjunctive (hypothetical): “If he were in charge, things would be different.”

How can you use this in your op-ed?

- To Pose a Hypothetical: It’s a great way to start your story and pull the reader in.

- “What if you were to walk a mile in her shoes? What if her reality were yours, just for a day?”

- “If every CEO were to spend one week working on their own factory floor, our conversations about wages might change.”

- To Make a Strong Suggestion: The subjunctive is used after verbs like “suggest,” “recommend,” “insist,” “ask,” and “demand.” The structure is Verb + that + subject + base form of the verb.

- “I suggest that the city council reconsider its position.” (Not “reconsiders”)

- “Her story demands that we take action now.” (Not “we takes” or “we took”)

- “It is essential that he be given a fair hearing.” (Not “he is given”)

Using the subjunctive mood adds a layer of formal, sophisticated persuasion to your writing. It signals to the reader that you are moving beyond simple facts into the realm of what could be or what should be. It frames your narrative not just as a story, but as a proposition for a better world.

Tip 3: The Narrative Arc in Miniature

Even a short vignette needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. It doesn’t have to be dramatic, but it needs movement.

- The Setup (The “Before”): Introduce your character and their ordinary world. Show us the status quo, the problem as it exists in their daily life. This is Mr. Henderson and his silent Tuesday.

- The Inciting Incident: Something small happens that changes the situation or highlights the problem. A new family moves in next door. A volunteer from a local charity calls him by mistake.

- The Climax/Turning Point (The “During”): This is the emotional core of your story. Mr. Henderson has a short, awkward, but deeply meaningful conversation with the new neighbor’s child. He realizes how much he has missed human connection.

- The Resolution (The “After”): Show the result of the change. It doesn’t have to be a fairytale ending. Maybe now his Tuesdays involve watching for the child to come home from school, a small but profound shift.

Putting It All Together

So, for your writing challenge, start by choosing your issue. Then, instead of brainstorming arguments, brainstorm a character. Give them a name. Put them in a specific situation. What do they want? What’s stopping them?

Write their story using vivid, sensory details and strong, active verbs. As you connect their personal struggle back to the larger issue, use the subjunctive mood to pose questions and make suggestions to your reader. “If Mr. Henderson were your father, what would you wish for him? His story insists that we create more programs to connect our communities.”

This approach turns your opinion from a lecture into a shared experience. And as we learned from the great literary levers of history, a shared experience is the most powerful catalyst for change.

Vocabulary Quiz

The Debate

The Debate Transcript

Welcome to the debate. Our source material today, well, it really forces us to confront a significant paradox. Historically, the physical book, you know, this quiet, slow medium, has actually been an explosive force for massive social and political upheaval, often dwarfing the speed and noise of our modern digital communications.

Right. And that brings us to the core question we’re tackling today, which is, does the unique, immersive mechanism of traditional literature, that sustained, focused narrative, does it still remain the most potent and, crucially, the most effective driver for achieving substantive, lasting political and social change in our current age, which is, let’s face it, completely saturated with digital information? Exactly. And I’ll be arguing that literature’s singular ability to cultivate a deep empathy and fundamentally humanize abstract political concepts makes it an irreplaceable force, a force for generating the profound moral shifts that are, I believe, necessary for any lasting reform.

And I’ll maintain that while literature is absolutely still influential, I mean, it serves as a crucial agenda setter, an intellectual touchstone, no doubt, its power has fundamentally, well, it’s evolved and I’d argue diminished, certainly in relative terms. The function of the slow, deep story, I think, has yielded the primary role to media mechanisms that prioritize speed, scale and, importantly, immediate evidence. OK, so my position is that we really cannot mistake the quiet nature of the book for a lack of power.

Literature isn’t just entertainment. It’s fundamentally, as the source puts it, a lever for the mind, a fulcrum for the heart. Its unique efficacy lies in what I’d call, well, psychological alchemy.

Think about the limitations of just raw data. We can be presented with cold statistics, you know, poverty rates, casualty numbers, incarceration percentages, and our minds, they sort of insulate themselves. The statistics often remain distant, abstract.

Literature, however, compels a unique cognitive process. It puts the reader inside the lived experience of a character, forcing the brain to simulate the circumstances of another person. When we read, say, of the Jode family’s desperation during the Dust Bowl or the impossible moral choices faced on a slave plantation, we’re bypassing the frontal lobe’s intellectual judgment in a way.

We move from knowing a fact to feeling a tragedy. And this visceral empathy, that’s what humanizes the abstract. It turns these complex political issues into felt human destiny.

And this transformation, I believe, turning political problems into moral imperatives, is the prerequisite for fundamental, enduring change. OK, I understand why you prize that depth. And I certainly don’t deny the the cataclysmic historical impacts of authors like Harriet Beecher Stowe or Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

And I mean, they wielded true revolutionary power. Absolutely. But we have to analyze the present environment, the ground upon which that lever rests.

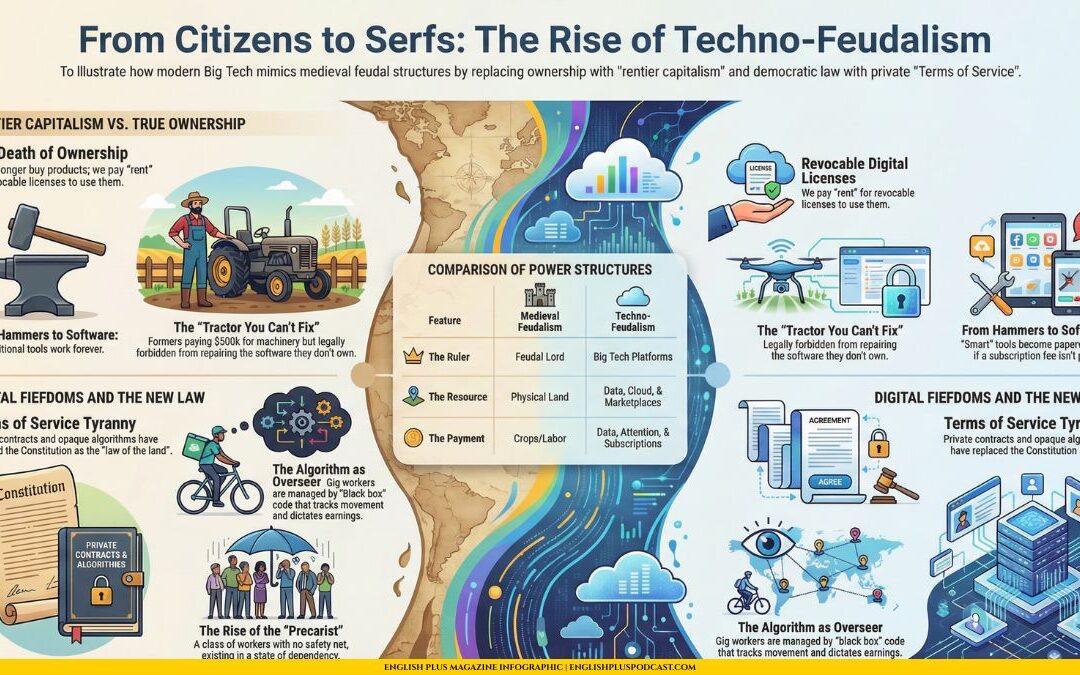

It’s shifted dramatically. The very element you celebrate, that focused quiet of a book that demands hours, sometimes days of undivided attention. That’s precisely what struggles to compete now in a context of just constant information inundation.

You think it struggles too much? I think it’s reach struggles. The modern listener, the modern citizen consumes news through headlines, social feeds, micro content. This behavior prioritizes, well, immediate action, statistical confirmation, often over the, say, three week moral investment, a complex novel demands.

And as a result, modern literary impact tends to function more like a like a slow release capsule of thought. It provides intellectual architecture. It sets an agenda like Silent Spring did.

Sure. Or it provides cultural language and iconography, you know, like the red robes from The Handmaid’s Tale. These books are powerful amplifiers, powerful context providers.

Absolutely. But they are rarely, I argue, the singular immediate cultural phenomenon that forces a sudden national political crisis. That initial spark of mass mobilization.

It’s now driven by faster mechanisms. I find that argument historically accurate in describing the shift in media consumption, but I believe it’s strategically flawed when we define potency. You emphasize scale and speed.

I emphasize depth and the the moral transforming quality. I’m just not convinced speed is a suitable replacement for genuine conviction. Let’s return to the empathy engine idea.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin. OK, it was sentimental fiction, yes, but it achieved something unique. It reframed the complex, distant political and economic issue of slavery into a profound moral and religious crusade in the north.

It gave a visceral face, a human story to millions who were previously just ignored by political discourse. A viral video. Sure, it can convey instant suffering, but that suffering is often fleeting, easily dismissed.

It doesn’t demand the sustained internal reflection needed to fundamentally dismantle a person’s entire view of a systemic issue. That profound, slow burn immersion. That’s what generated the political will for emancipation or war as it happened.

A transformation that I maintain cannot be achieved by a news headline or a fleeting image. I find the quality of that empathy undeniable, of course, but we cannot mistake quality for political potency, especially in the 21st century. You’re asking the public to commit to an investment of time that our current informational ecosystem actively discourages, often through quite sophisticated, algorithmically driven mechanisms.

So while the resulting empathy is high for a dedicated reader, the scale and the speed at which modern complex issues, think climate change policy, global pandemics, are initially understood and acted upon globally, that’s now overwhelmingly digital. It’s driven by network effects, by virality. A few million readers of a novel, no matter how deeply affected they are, well, they often can’t compete with billions exposed instantaneously to narratives and data that spur action, even if, admittedly, the understanding is less nuanced.

I’d submit that depth reaching only a self-selected few thousand today is perhaps a philosophical achievement, but maybe not a primary political mechanism for mass mobilization anymore. OK, but that leads us directly to the question of intellectual demolition then. If modern media is fast, can it truly achieve the systematic dismantling of an ideology that required the sustained argument of a book? Consider the case study of the Gulag Archipelago.

This was a single manuscript, smuggled out, disseminated, and we need to remember the method of transmission here, samizdad, you know, the illicit, often handwritten distribution of banned texts. That actually magnified its impact under censorship. This book functioned as a literary bomb.

Its power wasn’t just influential, it was demolitional. It systematically shattered the romanticized illusion of the Soviet Union for Western intellectuals, providing the sheer crushing weight of meticulously researched, weaponized truth. It exposed Soviet communism as a vast, murderous machine.

Now, that level of systematic intellectual and moral demolition required the scope, the density that really only a massive book can provide. You simply cannot use short form media to rewrite the moral framework of an entire geopolitical conflict. I can see that the systematic dismantling of an ideology requires scope.

Absolutely. But the historical cataclysms you cite, like Gulag or Uncle Tom’s Cabin, they occurred under conditions that really maximized the book’s singular impact. Think about it.

A less distracted public sphere, much more controlled information flow in many cases, that amplified the book. In the modern, open, frankly chaotic information environment, that singular effect is diluted. It requires the book to work differently.

Modern books that spark discussion, they seem less about the revelation of secrets and more about framing policy debates. Take a nonfiction like Matthew Desmond’s Evicted or maybe J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. These function almost as policy primers, wouldn’t you say? They bring complex academic research or sociological phenomena and package them into powerful human narratives.

Yes, but their success today is often measured by how quickly they’re adopted by think tanks, politicians and the rapid media cycles. They set the agenda, sure, but they don’t usually force the crisis on their own. Their political potency seems derived from their ability to be summarized, amplified digitally.

Not necessarily from the thousands of quiet hours spent reading the original text. The book becomes the raw material. The fast media is the refining and distributing mechanism.

See, I’m not convinced by that line of reasoning because it almost implies that the book is merely a footnote to the faster media. I think the quiet, focused attention demanded by a book is precisely what makes it potentially revolutionary in an age of noise. Because it offers the necessary space, the mental room, to actually grapple with complexity.

Which brings us to maybe our final point. How do we define substantive change? My argument is the deep, lasting, substantive change requires the moral transformation of the individual, which the book, I believe, achieves uniquely. It’s the difference between, say, temporarily changing a law and permanently shifting a core societal value.

And I understand the enduring value of transforming societal values. I really do. But when we look at political movements, potency is often measured by, well, immediate legislative outcomes, large-scale shifts in resource allocation, things happening now.

And I argue that today, large-scale policy shifts are sparked and driven not typically by a moral novel read over weeks, but by quick evidence data dumps, policy memos, rapid media reports that are consumed at scale. So while I acknowledge literature’s enduring ability to provide vital context, to frame the conversation over the long term, I maintain that speed is now a prerequisite for political potency. Can your empathy engine, powerful as it is, produce fundamental moral shifts quickly enough to counteract, say, state-sponsored disinformation or the sheer crisis fatigue that floods the digital sphere daily? The digital sphere seems to act as the dominant point of influence now, determining what policy gets attention right now.

Ultimately, my position remains that the power of literature is irreplaceable because its depth of impact on individual morality is simply unmatched by other forms. It fundamentally shifts how we view our shared humanity, offering that quiet space needed to build genuine conviction, which I see as the necessary prerequisite for any lasting social or political reform. And I conclude by emphasizing that while literature remains essential for setting the long-term intellectual and moral agenda, absolutely, the immediacy, the scale and the speed required to initiate and sustain mass movements today, well, they necessitate a shift in the primary driver of change towards faster media and direct evidence.

The slow, deep story is now, I believe, a vital catalyst, maybe a crucial foundation, but it has yielded the leading role to the digital sphere when it comes to mobilizing action. Thank you for listening to the debate. Remember that this debate is based on the article we published on our website, EnglishPlusPodcast.com. Join us there and let us know what you think.

And of course, you can take your knowledge in English to the next level with us. Never stop learning with English Plus Podcast. Thank you.

Let’s Discuss

Here are a few questions to get you thinking and talking more deeply about the power of literature. Share your thoughts and engage with others’ ideas—that’s how we build a richer understanding together.

What book, novel, or even short story has personally acted as a “lever” in your own life, fundamentally changing your perspective on a social, political, or personal issue?

Don’t just name the book; talk about what your perspective was before reading it. What specific character, scene, or idea created the shift? Was the change immediate and dramatic, or was it a slow burn that you only recognized later? Did it prompt you to take any real-world action, no matter how small?

In the age of social media, 15-second videos, and constant information overload, has the book lost its power as a tool for social change, or has its role simply evolved?

Consider the pros and cons. Is a viral hashtag more effective than a novel for immediate mobilization? Can a book offer a depth and nuance that social media can’t? Think about how modern movements use literature. Does a book like The Handmaid’s Tale gain more power through social media, as its imagery is shared and adapted online?

Can a work of fiction ever be “just a story”? Or do all narratives, consciously or not, carry a political or social message?

Think about your favorite “escapist” genres, like fantasy or science fiction. Do they reinforce or challenge societal norms about heroism, power, gender, or race? Consider the argument that the very act of choosing which characters to focus on and whose stories to tell is a political one. Is there a difference between a story with an agenda and a story that simply reflects the values of its time?

The article focuses on books that brought about positive change, but literature can also be used to reinforce negative stereotypes and promote harmful ideologies. Can you think of examples, and how do we reckon with that legacy?

This is a complex one. Think about older books that contain racist or sexist tropes that were common at the time. Should we stop reading them? Should they be read with historical context? What about books written explicitly as propaganda? Does the power of the “lever” mean that authors have a greater moral responsibility than other artists?

If you were to write a story today designed to be a “lever” for change on a specific issue, what issue would you choose, and what kind of story would you tell?

What contemporary problem do you think is most misunderstood or needs to be humanized? Would you use fiction or non-fiction? Would your story be realistic and gritty, or would you use allegory and fantasy to make your point? Who is the one character whose story you think the world needs to hear right now?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

It’s great to have this chance to elaborate on a few things. The main article provided a solid foundation, focusing on two monumental examples of literature as a social lever. But the landscape is, of course, far more vast and nuanced. Let’s delve into a few areas we might have only skimmed past.

First, let’s talk about the forms we overlooked. We focused heavily on the novel and narrative non-fiction, but we can’t forget poetry and drama. A play, for instance, is literature brought to life, a communal experience that can be incredibly potent. Think of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. On the surface, it’s about the Salem witch trials of 1692. But it was written in 1953, and for anyone watching it at that time, it was a searing, unmistakable allegory for the anti-communist “witch hunts” being led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. By using a historical setting, Miller was able to critique the present in a way that was both subversive and undeniable. He forced his audience to see the paranoia and hysteria of their own time reflected in the past. That’s a powerful lever. Poetry, too, has often been the language of revolution—from the protest poems of the Civil Rights era to the works of dissent smuggled out of authoritarian regimes. It’s concise, memorable, and emotionally charged, capable of capturing a complex idea in a single, powerful image.

Another critical dimension is the concept of “dangerous” literature—the very reason authoritarian regimes are so often the first to burn books. When a book is banned, it’s a backhanded compliment. It’s an admission by those in power that the ideas contained within those pages are a genuine threat to their control. The list of banned books throughout history is a veritable honor roll of world-changing literature. The efforts to suppress a book often amplify its message, turning it from a mere story into a symbol of resistance. Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses is a complex modern example. The fatwa issued against him turned the book into a global flashpoint for debates on free speech, religion, and artistic expression. The danger wasn’t just in the text, but in the world’s reaction to it.