- The Chasm of Feeling: Closing the Empathy Gap in the Exam Room

- The Monster Under the Bed: How the Availability Heuristic Shapes Our Health Fears

- The Wellness Fad Feedback Loop: How Confirmation Bias Makes Us Suckers

- The Magic Within: The Placebo Effect and the Power of Belief

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

Of all the decisions we make, those concerning our health feel the most sacred. When faced with a diagnosis, a treatment plan, or a new wellness regimen, we strive to be our most rational selves. We gather information, we weigh pros and cons, and we place our trust in the objective, data-driven world of medical science. We imagine a clean, clear line between the facts of our biology and the choices we make to preserve it.

But this sterile image of healthcare decision-making is a fantasy. The reality is that the path to wellness is a minefield of cognitive biases, for both patients and practitioners. Our ancient, evolved brains, with their glitches and shortcuts, don’t suddenly power down when we walk into a doctor’s office or a vitamin shop. In fact, in the emotionally charged atmosphere of health and medicine, these biases can become even more potent, distorting our fears, warping our beliefs, and creating a chasm of misunderstanding between those who give care and those who receive it.

This is not a cynical indictment of modern medicine or a dismissal of personal responsibility. It is an exploration of the invisible psychological forces that shape our most critical choices. By understanding how our minds process—and often misprocess—information about our own bodies, we can become better patients, more empathetic practitioners, and more discerning consumers of wellness. It’s time to diagnose the biases that influence our health, not to eliminate them, but to manage their symptoms.

The Chasm of Feeling: Closing the Empathy Gap in the Exam Room

Imagine this scene: A patient sits on an exam table, shivering in a paper gown, their mind racing with anxiety. Their back pain is a searing, 10-out-of-10 reality that eclipses everything else. They are in a “hot state”—a visceral, emotional condition dominated by immediate feelings like pain, fear, or hunger.

Across from them sits a doctor. The doctor is calm, analytical, and has seen twenty other patients with back pain this month. They are working through a diagnostic checklist, considering probabilities, and thinking about treatment protocols. They are in a “cold state”—a rational, detached condition where logic and planning take precedence.

This disconnect is known as the Empathy Gap. It’s our profound inability, when in one emotional state, to accurately appreciate or predict how we would feel or behave in another. When we are in a “cold” state, we consistently underestimate the influence of “hot” states on our own and others’ behavior.

The doctor, in their cold state, may struggle to fully grasp the all-consuming nature of the patient’s pain. They might logically conclude that the pain is manageable with over-the-counter medication and rest, underestimating the patient’s desperation for immediate, powerful relief. The patient, in their hot state, may perceive the doctor’s calm demeanor not as professionalism, but as a lack of concern or belief in their suffering. This gap can lead to tragic misunderstandings, with patients feeling dismissed and doctors feeling frustrated by what they perceive as patient non-compliance or exaggeration.

How to Bridge the Empathy Gap

- For Patients: Translate Your “Hot State” into “Cold” Data: Your feeling is real, but a feeling is hard for a clinician to measure. Try to translate your subjective experience into objective information. Instead of just saying “it hurts a lot,” say, “The pain prevents me from sleeping more than two hours at a time,” or “I am unable to bend down to tie my shoes.” This frames the problem in terms of functional impact, which is a language the “cold state” brain can more easily process and act upon. Keep a simple journal of your symptoms to present concrete patterns.

- For Doctors: Use “Affective Forecasting”: Before dismissing a patient’s anxiety or pain level, practitioners can consciously ask themselves: “If I were in this person’s shoes—uncertain about my health, in constant pain, and navigating this confusing system—what would my primary emotional needs be right now?” This act of prospective empathy can prompt small but crucial actions, like making more eye contact, using validating language (“I can see this has been incredibly difficult for you”), and explaining the why behind a treatment plan to address the fear of the unknown.

- Shared Decision-Making: This model reframes the doctor-patient relationship from a monologue to a dialogue. The doctor brings their clinical expertise, and the patient brings their life expertise—their values, fears, and priorities. By making the decision together, both parties are forced to cross the empathy gap and appreciate the other’s perspective.

The Monster Under the Bed: How the Availability Heuristic Shapes Our Health Fears

Which are you more afraid of: dying in a shark attack or dying from a bee sting? For most people, the answer is the shark. Yet, you are orders of magnitude more likely to die from a bee sting. Why the disconnect? The Availability Heuristic.

This is our mental shortcut of judging the likelihood of an event by how easily examples of it come to mind. Events that are dramatic, recent, emotionally charged, and heavily covered by the media are highly “available.” Shark attacks make for spectacular news stories. The quiet, common death from a bee sting (often due to anaphylactic shock) does not.

In health, this bias dictates our anxieties. We worry obsessively about rare brain tumors, Ebola outbreaks, or exotic diseases we saw in a movie, all of which are highly available in our minds. Meanwhile, we neglect the far greater, but less “available,” threats of heart disease, diabetes, and stroke—the silent, lifestyle-driven killers that are responsible for the vast majority of premature deaths. The media’s relentless focus on dramatic medical crises rather than preventative public health creates a distorted map of risk in our heads. We end up misallocating our most precious resources—our worry and our attention—to the wrong threats.

How to Correct Your Mental Map of Risk

- Consult Statistics, Not Stories: When you feel a surge of anxiety about a particular disease or health risk, stop. Before you fall down a rabbit hole of terrifying anecdotes online, actively seek out the base rates. Go to reliable sources like the World Health Organization (WHO) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ask: “How common is this, really? What is my actual statistical risk?” Replacing vivid stories with boring data is a powerful antidote.

- Notice the Media’s Influence: Practice media literacy. When you see a health story, ask yourself why it’s being covered. Is it because it represents a widespread, significant threat, or because it’s novel, scary, and generates clicks? Recognizing that the news is a curated selection of the most dramatic events, not a reflection of everyday reality, helps you discount its emotional impact.

- Focus on the “Boring” Risks: Make a conscious effort to shift your attention. Spend less time worrying about the “shark” and more time managing the “bees.” Focus your energy on the things that statistics show have the biggest impact on longevity and healthspan: diet, exercise, sleep, stress management, and not smoking. These preventative measures are less exciting, but they are the most powerful medicine we have against the most probable dangers.

The Wellness Fad Feedback Loop: How Confirmation Bias Makes Us Suckers

Have you ever decided a new diet or supplement is the answer to your prayers, and then suddenly, everywhere you look, you see evidence that you’re right? Testimonials on social media, articles from wellness bloggers, and success stories from friends all seem to validate your choice. This isn’t serendipity; it’s Confirmation Bias at work.

This is the mother of all biases, our potent tendency to seek out, favor, and recall information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs, while simultaneously ignoring or discrediting information that contradicts them. Once we believe that, say, the “celery juice cleanse” is the key to good health, our brain goes to work like a biased detective, gathering only the evidence that supports our theory.

The wellness industry, with its deluge of conflicting information and charismatic gurus, is a perfect petri dish for this bias to flourish. We find a theory that appeals to our intuition or offers a simple solution to a complex problem, and we commit. Then, we curate our information feeds to create an echo chamber, following influencers who promote our chosen path and unfollowing those who critique it. We dismiss rigorous scientific studies that show no effect as “funded by big pharma,” while elevating a single, compelling anecdote to the status of gospel truth. Confirmation bias doesn’t just lead us to a bad decision; it locks us into it.

How to Escape the Wellness Echo Chamber

- Actively Seek Disconfirming Evidence: This is the core discipline. Before you fully commit to any new wellness trend, make it a rule to spend an equal amount of time actively searching for the counter-argument. Use search terms like “[Wellness Trend] criticism,” “[Supplement Name] debunked,” or “[Diet Name] scientific evidence.” Forcing yourself to engage with the strongest arguments against your belief is the only way to test its true strength.

- Distrust Your Gut (Especially When It Feels Great): That satisfying “aha!” feeling you get when you find information that supports your belief? That’s the feeling of confirmation bias. Learn to be skeptical of that feeling. Treat it as a warning sign that your critical thinking might be shutting down. The path to truth often feels uncertain and complicated, not simple and satisfying.

- Create an “Intellectual Out”: Before you start, define what would convince you that you’re wrong. What specific results do you expect to see, and by when? If after three months of the new regimen, your objective health markers (like blood pressure or cholesterol, not just subjective feelings) haven’t improved, would you be willing to abandon it? Setting a clear “off-ramp” beforehand makes it easier to quit a failing strategy without feeling like a personal failure.

The Magic Within: The Placebo Effect and the Power of Belief

No discussion of bias in health would be complete without touching on the most enigmatic and powerful phenomenon of all: the Placebo Effect. A placebo is a substance or procedure with no therapeutic value—like a sugar pill or a sham surgery—that can nonetheless produce a real, measurable physiological response in a patient simply because they believe it will work.

Patients given a placebo have been shown to experience genuine pain relief, reduced inflammation, and even improved motor function in conditions like Parkinson’s disease. The placebo effect is not “all in your head” in the sense of being imaginary; it is a stunning demonstration that our beliefs, expectations, and the rituals of medicine can create tangible changes in our body’s chemistry. It is the ultimate belief-based bias, where the mind’s prediction literally becomes the body’s reality.

While often discussed in the context of clinical trials (as something to be controlled for), the placebo effect is a constant, powerful force in all healthcare interactions. The doctor’s confident demeanor, the pristine white coat, the fancy medical equipment—all of these are part of the therapeutic ritual and contribute to the patient’s expectation of getting better. This is the “good” side of bias, the one we can potentially harness.

How to Harness the Placebo Effect (Ethically)

- Optimize the Healing Context: As a patient, you can enhance the placebo effect by creating positive expectations. Choose practitioners you trust and with whom you have a good rapport. Before a procedure, visualize a positive outcome. Engage in the rituals of care—taking your (real) medication at the same time each day, for example—with intention and a belief in its efficacy.

- Focus on Meaning and Narrative: For both patients and doctors, understanding that the story matters is key. A doctor who frames a treatment not just as a chemical intervention but as a way to help a patient “get back to gardening” or “be able to play with their grandkids” is tapping into the meaning-making part of the brain, which can amplify the healing response.

- Recognize Its Role in Alternative Medicine: Many alternative and complementary therapies may have limited scientific evidence for their specific proposed mechanism, but they are often masters at maximizing the placebo effect. They provide long consultations, empathetic listening, elaborate rituals, and a powerful narrative of healing. Recognizing this doesn’t necessarily invalidate the patient’s experience of feeling better, but it does provide a scientific framework for understanding why it might be working, separate from the therapy’s specific claims.

Our health is the most complex system we will ever manage. Navigating it requires not just good science, but good psychology. It requires us to be humble about the certainty of our beliefs, curious about the source of our fears, and deeply empathetic to the emotional reality of others. By becoming aware of the biases that operate within us, we can make healthier choices, build stronger therapeutic alliances, and better navigate the profound and mysterious connection between our minds and our bodies.

MagTalk Discussion

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Let’s dive into some of the language we chose for that article. The goal is to use words that are not just descriptive but also carry a specific nuance and power. Getting comfortable with these words can really elevate the way you express your ideas. We’re going to walk through about ten of them, talking about them like we’re just having a conversation.

First off, let’s look at the word sacred. We said that decisions about our health feel the most “sacred.” Sacred means connected with God or dedicated to a religious purpose and so deserving veneration. But we also use it in a secular way to mean something that is regarded with great respect and reverence, something too valuable or important to be interfered with. The bond between a parent and child can be described as sacred. The principle of free speech is sacred to a democracy. By calling health decisions sacred, we’re immediately establishing their immense personal importance, setting the stage for why it’s so critical to get them right.

Next, we have the word chasm. We used it to describe the “chasm of misunderstanding” between doctors and patients. A chasm is a deep fissure or crack in the earth, rock, or another surface. It’s a canyon, a gorge. Metaphorically, it refers to a profound difference between people, viewpoints, or feelings. You might talk about the chasm between the rich and the poor, or the chasm between two generations. It’s a much more dramatic and powerful word than “gap” or “difference.” It paints a picture of a vast, deep, and difficult-to-cross divide, which perfectly captures the essence of the Empathy Gap.

Let’s talk about eclipses. The article said a patient’s pain “eclipses everything else.” An eclipse is, of course, an astronomical event where one celestial body blocks the light from another. As a verb, to eclipse something means to obscure or block it out, or, more powerfully, to make it seem insignificant by comparison. A stunning performance by one actor can eclipse all the others in a play. A major world event can eclipse all other news stories. It’s a beautiful, visual verb that conveys total dominance. The pain doesn’t just distract; it completely overshadows every other thought and feeling.

Then there is the adjective visceral. We described a “hot state” as a “visceral, emotional condition.” Visceral relates to deep inward feelings rather than to the intellect. It’s a gut feeling. It comes from the viscera—the internal organs in the main cavities of the body. A visceral reaction is one you feel in your gut; it’s instinctual, not logical. You might have a visceral hatred of a certain food or a visceral fear of heights. It’s a fantastic word to describe a powerful, physical, and non-rational response.

How about orders of magnitude? We said you are “orders of magnitude more likely to die from a bee sting” than a shark attack. This is a great phrase from science and mathematics. An order of magnitude is a factor of ten. So if something is one order of magnitude larger, it’s 10 times larger. Two orders of magnitude means 100 times larger. Three means 1,000 times larger, and so on. It’s a very precise and impactful way to say “much, much more” or “vastly.” It signals that the difference isn’t just large, it’s exponentially large.

Let’s look at serendipity. When discussing Confirmation Bias, we said finding evidence for a new diet isn’t “serendipity.” Serendipity is the occurrence of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way. It’s a happy accident. Finding a $20 bill on the street is serendipity. Bumping into an old friend in a foreign city is serendipity. It’s a beautiful word for fortunate chance. By contrasting it with Confirmation Bias, we highlight that what feels like a lucky discovery is actually a predictable result of our own biased searching.

Next, a great word: deluge. We mentioned the “deluge of conflicting information” in the wellness industry. A deluge is a severe flood. Like chasm, it’s a powerful natural metaphor. In common usage, it means a great quantity of something arriving at the same time. You might receive a deluge of emails after a vacation or face a deluge of questions after a presentation. It conveys a sense of being overwhelmed by a massive, rushing inflow of something, which perfectly captures the modern information environment.

Then we have gospel truth. We said we can elevate an anecdote to the status of “gospel truth.” The Gospel, in a religious sense, refers to the teachings of Jesus Christ. To take something as gospel truth means to believe it is absolutely and unquestionably true. It’s a strong idiom for complete and utter belief. If your grandmother is a great cook, you might take her recipes as gospel truth. It implies a level of faith that goes beyond normal evidence.

Let’s talk about enigmatic. We called the placebo effect the most “enigmatic and powerful phenomenon.” Enigmatic means difficult to interpret or understand; mysterious. It comes from the word enigma, which is a puzzle or a riddle. An enigmatic smile is one you can’t quite read. An enigmatic character in a novel is one whose motivations are unclear. It’s a wonderful word for something that is fascinating precisely because it’s hard to fully figure out.

Finally, we used the word rapport. We said you should choose practitioners with whom you have a good “rapport.” Rapport is a close and harmonious relationship in which the people or groups concerned understand each other’s feelings or ideas and communicate well. It’s that feeling of being “in sync” with someone. A good teacher has a great rapport with her students. Two musicians who play well together have a strong rapport. It’s a key ingredient for any successful therapeutic or collaborative relationship.

So there you go: sacred, chasm, eclipses, visceral, orders of magnitude, serendipity, deluge, gospel truth, enigmatic, and rapport. Ten words that can add precision, imagery, and sophistication to your communication.

Now for our speaking skill. Today, let’s focus on acknowledging and validating someone’s feelings before presenting a different perspective. This is a cornerstone of empathetic communication, and it’s directly related to bridging the Empathy Gap. When someone is in a “hot state” (anxious, in pain, angry), you cannot reach them with logic until you have acknowledged their emotional reality. Instead of starting with “Actually, you’re wrong,” you start with “I hear you,” or “That sounds incredibly frustrating.”

Look at how the advice for patients was framed in the article: “Your feeling is real, but…” Or how the advice to doctors started with validating language. This “Yes, and…” or “I understand, but…” structure is incredibly powerful. It lowers defenses and makes the other person receptive to what you have to say next.

Here’s your speaking challenge: Find a friend or family member and have a conversation about a topic you mildly disagree on. It could be about a movie, a recent news event, or a local issue. Your mission is to practice the “A-V-P” technique: Acknowledge, Validate, then present your Perspective. Before you state your own opinion, you must first verbally acknowledge their point and validate the feeling or logic behind it. For example: “I can see why you feel that way about the ending; it was definitely surprising and left a lot of questions unanswered. For me, I kind of liked that ambiguity because…” Record yourself if you can, or just reflect on it afterward. How did it change the dynamic of the conversation? Did the other person seem more open to your idea? This skill will transform your ability to have productive disagreements.

Grammar and Writing

Welcome to the writing lab. Today’s challenge is about navigating one of the most delicate communication tasks there is: talking to someone about a questionable health choice. This requires a masterful blend of clarity, empathy, and persuasion.

The Writing Challenge:

Write a compassionate and persuasive letter or email (around 500-750 words) to a close friend who has enthusiastically embraced a new, unproven wellness fad. Imagine this fad involves a restrictive diet and expensive, proprietary supplements they found online. They are convinced it’s curing a range of non-specific ailments, but you are concerned about the lack of scientific evidence and the potential harm.

Your letter must:

- Open with Connection and Support: Start by affirming your friendship and acknowledging their positive intentions and the improvements they feel they’re experiencing.

- Gently Introduce Doubt (without Accusation): Using your knowledge of Confirmation Bias and the Placebo Effect, gently question the source of the benefits without questioning your friend’s actual experience.

- Provide an Alternative Framework: Explain the concepts of Confirmation Bias and the Placebo Effect in simple, relatable terms. Frame them as normal human psychology, not as a sign of your friend’s foolishness.

- Express Your Core Concern: Clearly and lovingly state your specific worry (e.g., about the diet’s restrictiveness, the cost, the lack of medical oversight).

- Suggest a Collaborative “Next Step”: Propose a low-stakes, collaborative action, such as researching it together, looking at scientific sources, or suggesting they discuss the supplements with their doctor.

This is a tightrope walk. You need to be a good friend first and a critical thinker second. Let’s look at the grammar and writing techniques that will help you keep your balance.

Grammar Spotlight: I-Statements and Question-Posing

When you want to express concern without sounding accusatory, the grammatical structure of your sentences is paramount. Two powerful tools are I-Statements and strategic question-posing.

- I-Statements: An “I-Statement” focuses on the speaker’s feelings, beliefs, and concerns rather than on the listener’s actions. It takes the form of “I feel [emotion] when [behavior] because [reason].” This structure avoids the accusatory “You-Statement” (“You are being foolish”).

- Instead of (You-Statement): “You are falling for a scam and ignoring all the evidence.”

- Try (I-Statement): “I get worried when I see how much money you’re spending on this, because I want to make sure you’re safe and not being taken advantage of.”

- Instead of: “You’re not being scientific about this.”

- Try: “I feel a bit uneasy about the lack of scientific studies, because I know how much you value making informed decisions.”

I-Statements are non-confrontational. They don’t assign blame; they express personal feeling, which is impossible to argue with. The other person can’t say, “No, you don’t feel worried.” It shifts the conversation from a debate about their actions to a discussion about your relationship and concern.

- Strategic Question-Posing: Questions are less threatening than statements. They invite reflection rather than demanding agreement. Well-posed questions can gently lead your friend to the conclusions you want them to reach on their own.

- Instead of (Statement): “This diet is not sustainable.”

- Try (Question): “I’m curious, what does the long-term plan for this diet look like?”

- Instead of: “The ‘evidence’ you sent me is just testimonials.”

- Try: “That’s a really powerful story. I wonder, have we been able to find any clinical trials or studies that back up these kinds of results? What would be the best way to look for that?”

Use open-ended questions (starting with What, How, Why, I wonder…) to encourage thought, not yes/no answers.

Writing Technique: The “Praise-Question-Pivot” Sandwich

This is a classic structure for giving difficult feedback or expressing concern in a way that can be heard.

- Praise (The Top Slice of Bread): Start with genuine praise and validation. This is where you affirm their experience and your friendship.

- Example: “I’m so glad we caught up the other day, and I’m genuinely happy to hear you’ve been feeling more energetic lately. It’s awesome that you’re taking such an active role in your own health and trying to find things that work for you.”

- Question (The “Meat” of the Message): This is where you introduce your concerns, using your I-Statements and strategic questions. You gently reframe their experience through the lens of psychology.

- Example: “As I was thinking about it more, I got a little curious. You know how the mind is such a powerful thing? I was reading about the Placebo Effect, where just the belief in a treatment can create real change. I wonder if some of the benefits could be coming from that powerful mind-body connection? Also, I get a little concerned when I think about the diet part, because I’d hate for you to be missing out on any important nutrients.”

- Pivot (The Bottom Slice of Bread): Pivot back to collaboration and a positive, forward-looking action. Reaffirm your role as a supportive friend.

- Example: “You know I’m always on your team. What if we spent an hour this weekend just looking into some of the science behind it together? Maybe we could even find some articles to print out and show your doctor at your next check-up, just to get their take. Whatever you decide, I’m here for you.”

This “sandwich” approach makes the difficult message more palatable. You start and end with connection, which makes the recipient far more likely to engage with the challenging ideas in the middle. By mastering these grammatical and structural techniques, you can write a letter that is both deeply loving and powerfully persuasive.

Vocabulary Quiz

Let’s Discuss

These questions are designed to help you connect the abstract concepts of bias to your real-life experiences with health and wellness. Use them to spark a conversation or for personal reflection.

- Bridging the Empathy Gap: Think about a time you felt a doctor or other healthcare provider didn’t fully understand your pain, anxiety, or concerns. What could they have said or done differently to bridge that “empathy gap”?

- Dive Deeper: Now flip it. Have you ever been in a “cold state” and struggled to understand someone else’s “hot state” (e.g., a friend having a panic attack, a child having a tantrum)? What did that experience teach you about the difficulty of empathy? How could you apply the lessons from the article to better support them?

- Your “Availability Heuristic” Fears: What health concern do you worry about more than the statistics might warrant? Where does that fear come from? Is it from a news story, a movie, or a personal anecdote from a friend?

- Dive Deeper: Now consider the “boring” risks. What is one small, concrete change you could make to your daily routine to address a more statistically probable health risk (like heart disease or diabetes) that you currently don’t spend much time thinking about?

- Myths and Fads: What’s the most compelling wellness fad you’ve ever encountered or even tried? What made it so appealing?

- Dive Deeper: Looking back, can you see Confirmation Bias at work? How did you find information that supported it? Did you ever actively seek out disconfirming evidence? What would it take for a believer in a wellness trend (whether it’s you or someone you know) to change their mind?

- Harnessing Your Placebo Effect: The placebo effect demonstrates the incredible power of the mind. Think about your own life. What “rituals” or “contexts” make you feel healthier or more positive, even if they have no direct medical effect?

- Dive Deeper: This could be anything from having a cup of herbal tea when you feel a cold coming on, to the calming atmosphere of a yoga studio, to the confidence a particular doctor inspires in you. How can you consciously and ethically use this mind-body connection to support your overall well-being?

- Navigating Information Overload: The wellness world is a “deluge” of conflicting information. What’s your personal strategy for deciding who and what to trust when it comes to health advice?

- Dive Deeper: How do you differentiate between a charismatic influencer and a credible expert? What are your go-to sources for reliable health information? How do you handle it when a friend or family member enthusiastically shares health advice that you know is scientifically baseless?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

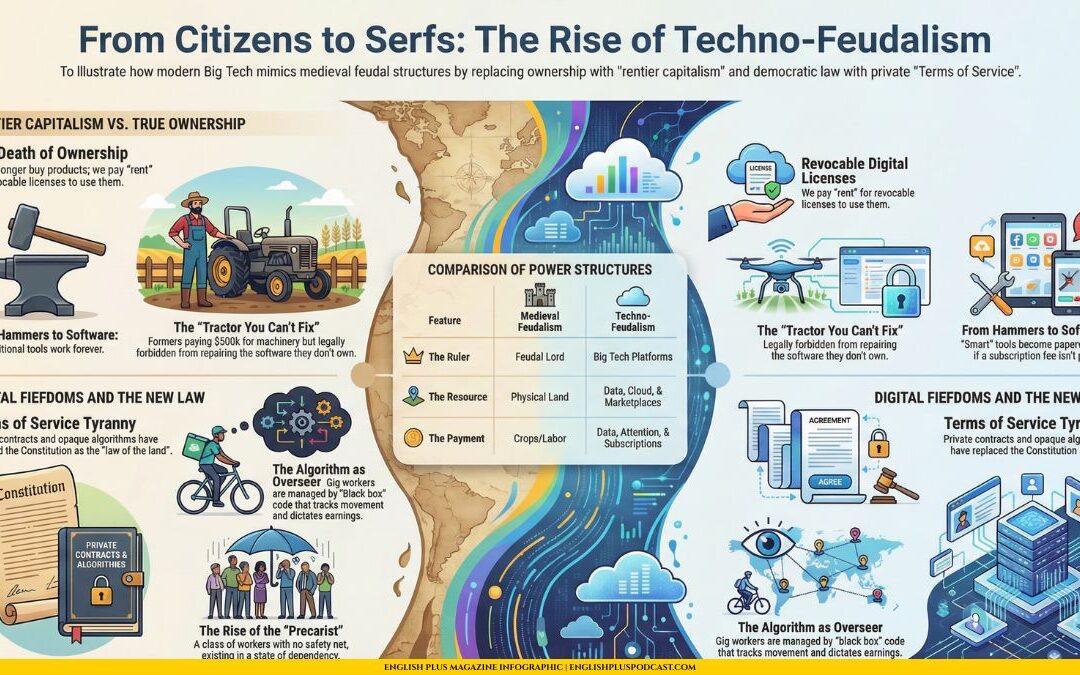

It’s been a great journey through some of the most prominent biases in healthcare. We’ve talked about the patient-doctor relationship, our fears, and our fads. But there’s a subtle, systemic bias that underpins many of these issues, one that affects both patients and doctors profoundly. I’m talking about Action Bias.

Action Bias is the powerful, instinctual impulse to do something rather than nothing, even when inaction is the more rational course. In a situation of ambiguity or high stakes—like a health crisis—our brains scream at us to act. Sitting and waiting feels like helplessness; taking action, any action, feels like taking control.

This bias is a huge driver of over-treatment in modern medicine. A patient comes in with a viral infection for which antibiotics are useless. The doctor knows this. But the patient is anxious and expects a prescription. The doctor, feeling the pressure to “do something” and alleviate the patient’s distress (and perhaps to hurry the appointment along), gives in and writes the script. This single act, multiplied millions of times, contributes to the global crisis of antibiotic resistance. Both patient and doctor have succumbed to Action Bias.

We also see it in end-of-life care, where families might push for aggressive, invasive, and painful treatments for a terminally ill loved one, even when those treatments have no realistic chance of success and will only diminish the patient’s quality of life. The inability to “do nothing”—to accept the inevitable and shift the focus to palliative care—is a painful manifestation of Action Bias. It feels better to fight a losing battle than to not fight at all.

For patients, Action Bias fuels a constant search for the next supplement, the next diet, the next “biohack.” It’s the feeling that we should always be optimizing, intervening, and acting upon our bodies. This can lead to a frantic cycle of trying and abandoning wellness fads, never giving our bodies the simple, boring, and slow gifts of rest and homeostasis. Sometimes, the healthiest choice is to stop acting and just let the system be.

So, a debiasing technique we didn’t cover is the conscious embrace of “watchful waiting” or “masterly inactivity.” This is the practice of deliberately choosing inaction as a strategic choice. It requires reframing “doing nothing” not as a sign of passivity or failure, but as a valid and often superior therapeutic option.

To do this, we need to learn to ask a different set of questions. For doctors, it’s: “What is the harm of acting versus the harm of not acting?” For patients, it’s: “Is my desire for this pill/supplement/diet driven by a genuine, evidence-based need, or by an emotional intolerance for uncertainty and a desire to feel in control?”

Learning to be comfortable with inaction is one of the most advanced, and most difficult, skills in navigating modern medicine and wellness.

0 Comments