- The First Rule of Bias Club: You Are a Member of Bias Club

- The Detective’s Field Journal: Tracking Your Thoughts

- The Art of the Pause: Mindfulness as a Magnifying Glass

- The Most Wanted List: Spotting Common Culprits

- The Verdict: A Lifelong Investigation

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

We fancy ourselves rational creatures. We imagine our minds as pristine, well-oiled machines, processing data from the world and spitting out logical conclusions. We make decisions, form opinions, and navigate our lives based on what we believe to be an objective reality. It’s a comforting thought, a cornerstone of our self-perception. It’s also, for the most part, a complete and utter fantasy.

The human brain, for all its marvels, is not a supercomputer. It’s more like a fantastically clever, but profoundly lazy, personal assistant. Its primary job isn’t to find the absolute truth; it’s to help you survive long enough to pass on your genes. To do this, it has developed an arsenal of mental shortcuts, or heuristics. These shortcuts allow us to make snap judgments and quick decisions, which was incredibly useful when deciding if that rustling in the bushes was a saber-toothed tiger or just the wind. In our complex modern world, however, these same shortcuts often lead us astray. They become cognitive biases: systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. They are the invisible architects of our thoughts, quietly constructing our reality without our consent.

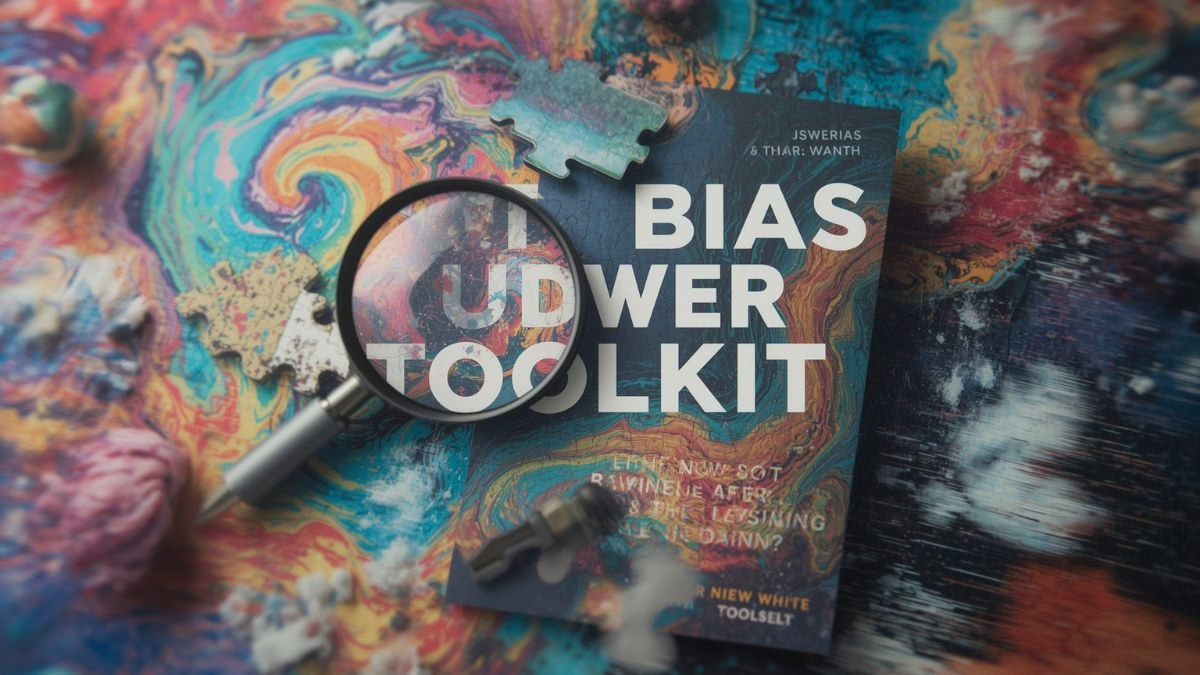

This isn’t an article about how to eliminate bias. That’s an impossible, and perhaps even undesirable, goal. This is an article about becoming a bias detective. It’s about learning to spot the fingerprints of flawed thinking on the crime scene of your own mind. The primary tool for this investigation is something called metacognition—the skill of thinking about your own thinking. It’s about turning your attention inward, not with judgment, but with curiosity. It’s time to open your toolkit.

The First Rule of Bias Club: You Are a Member of Bias Club

The biggest hurdle to becoming a bias detective is, ironically, a bias itself. It’s called the bias blind spot. This is the pervasive tendency for people to see the existence and impact of biases in others, while failing to see them in themselves. You can read a list of twenty common cognitive biases and nod along, thinking, “Oh yeah, my uncle does that all the time,” or “That perfectly describes my boss.” But when the spotlight turns on you? Suddenly, you’re the exception. Your beliefs are the product of careful analysis and hard-earned experience. Theirs are the result of sloppy, biased thinking.

This isn’t just arrogance; it’s a feature of how our brains protect our self-esteem. Admitting that our thinking is flawed can feel like a personal failing. It’s much more comfortable to believe we have a privileged, unvarnished view of the world. But to begin our detective work, we must first suspend this illusion. We must cultivate a dose of intellectual humility.

Intellectual humility isn’t about thinking you’re unintelligent. It’s the recognition that the knowledge you possess is finite and fallible. It’s the understanding that, no matter how smart or well-informed you are, you are operating with incomplete information and a brain that is hardwired for shortcuts. It’s the simple, yet profound, admission: “I might be wrong.” Embracing this mindset is the entry ticket. It’s what allows you to start looking for clues instead of just defending your initial conclusions.

How to Cultivate Intellectual Humility

- Embrace the phrase “I don’t know.” It’s not a sign of weakness; it’s a sign of strength. It opens the door to learning rather than slamming it shut with a premature conclusion.

- Actively seek out dissenting opinions. Don’t just tolerate them; hunt for them. Read books, articles, and follow commentators who challenge your worldview. The goal isn’t necessarily to change your mind, but to understand the rationales of those who think differently. This stretches your cognitive flexibility and highlights the assumptions underpinning your own beliefs.

- Argue against yourself. Before settling on a strong opinion, take a moment to genuinely try to build the best possible case for the opposite view. This practice, known as steel-manning (the opposite of straw-manning), forces you to engage with the strongest points of the opposition and can reveal weaknesses in your own logic.

The Detective’s Field Journal: Tracking Your Thoughts

A detective without a notebook is just a person with suspicions. To move from vague feelings to concrete patterns, you need to document your thinking. The most powerful tool for this is a decision journal. This isn’t a “Dear Diary” where you pour out your emotions (though that has its own benefits). A decision journal is a logbook of your thought processes during significant choices.

The goal is to create a record of what you were thinking before the outcome is known. Our memories are notoriously unreliable, constantly being revised by a pesky phenomenon called hindsight bias, the “I-knew-it-all-along” effect. After an investment pays off, we remember being supremely confident. After a project fails, we recall seeing the warning signs from the start. A journal cuts through this fog, preserving the scene as it actually happened.

How to Keep a Decision Journal

Your journal doesn’t need to be a leather-bound tome. A simple notebook or a digital document will do. For any non-trivial decision (e.g., taking a new job, making a significant purchase, having a difficult conversation), record the following:

- The Situation: What is the decision I need to make? What is the context?

- The Options: What are the main paths I am considering?

- The Mental State: How am I feeling right now? (e.g., rushed, anxious, excited, tired). Our emotional state has a colossal impact on our decisions, often in ways we don’t appreciate.

- The Variables: What are the key factors I believe will influence the outcome? What are my assumptions?

- The Prediction: What do I expect to happen? What is my level of confidence in this prediction (on a scale of 1-10)?

- The Review: Set a calendar reminder for a future date (a week, a month, a year later) to review the entry. Compare the actual outcome to your prediction.

Reviewing your journal is where the magic happens. You’ll start to see patterns. Maybe you consistently overestimate your ability to finish projects on time (Planning Fallacy). Perhaps you give too much weight to a single, vivid piece of information, like a friend’s dramatic story, while ignoring broader statistics (Availability Heuristic). Maybe you notice a tendency to stick with your initial plan even when new evidence suggests it’s failing (Sunk Cost Fallacy). You’re not just guessing anymore; you have data. You have clues.

The Art of the Pause: Mindfulness as a Magnifying Glass

Cognitive biases thrive in the space between a stimulus and your reaction. They are the engine of automatic, impulsive thought. An email from your boss with the subject line “URGENT” triggers an immediate stress response. A news headline that confirms your political beliefs triggers a satisfying rush of validation. An investment tip from a confident friend triggers an immediate urge to buy. The key to interrupting this process is to create a moment of space. This is the core practice of mindfulness.

Mindfulness, in this context, isn’t about emptying your mind or achieving a state of perpetual bliss. It’s about paying attention to the present moment, on purpose, without judgment. It’s the practice of observing your thoughts and feelings as they arise, rather than being swept away by them. This creates a crucial pause, a mental buffer zone. In that buffer zone, the bias detective can get to work.

When you feel a strong emotional reaction or a powerful urge to jump to a conclusion, that’s your signal. That’s the moment to pause. Instead of immediately reacting, you can ask a few simple questions:

- “What am I feeling right now?”

- “What thought just went through my head?”

- “What story am I telling myself about this situation?”

This simple act of observation short-circuits the automatic pilot. It gives your slower, more deliberate, and more rational thinking system—what psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls “System 2″—a chance to come online and review the work of the fast, intuitive “System 1.”

A Practical Mindfulness Exercise: The S.T.O.P. Technique

You can use this simple technique anytime you feel yourself getting hooked by a strong opinion or emotion.

- S – Stop: Whatever you’re doing, just pause for a moment.

- T – Take a Breath: Take one or two slow, deep breaths. This simple physiological act can help calm your nervous system and interrupt the fight-or-flight response.

- O – Observe: Notice what’s happening. What are the thoughts racing through your mind? What emotions are present in your body (e.g., tightness in the chest, heat in the face)? What is the impulse you feel (e.g., to send an angry email, to agree without thinking)? Just observe it all as you would watch clouds passing in the sky.

- P – Proceed: Having taken this brief pause to gather yourself and your data, you can now choose how to proceed more intentionally. You might still send the email, but perhaps with a more measured tone. You might still agree, but with a better understanding of why.

The Most Wanted List: Spotting Common Culprits

While there are hundreds of documented cognitive biases, a few usual suspects are responsible for the majority of our flawed thinking. Learning to recognize their signatures is a core skill for any bias detective.

Suspect #1: Confirmation Bias

This is the kingpin, the alpha bias. Confirmation Bias is our tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms or supports our preexisting beliefs. It’s why we tend to consume media that aligns with our political views and socialize with people who think like us. It feels good to have our beliefs validated. The algorithm-driven nature of social media and news feeds has supercharged this bias, creating personalized echo chambers where our own views are reflected back at us ad infinitum.

- Detective’s Question: “Am I genuinely trying to understand this, or am I just looking for evidence to support what I already believe? Have I made an equal effort to find disconfirming evidence?”

Suspect #2: The Anchoring Effect

This bias describes our heavy reliance on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions. Once an anchor is set, other judgments are made by adjusting away from that anchor, and there is a bias toward interpreting other information around it. This is a staple of negotiation. The first price thrown out, no matter how outlandish, sets the anchor for the rest of the conversation. It’s also why a “suggested retail price” next to a sale price makes the deal look so much better.

- Detective’s Question: “Is my judgment being overly influenced by the first number or fact I heard? What if that initial information was completely different? How would my thinking change?”

Suspect #3: The Dunning-Kruger Effect

This is a particularly tricky one. The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias whereby people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. Essentially, they are too incompetent to recognize their own incompetence. Conversely, experts often underestimate their own competence, assuming that tasks easy for them are also easy for others. This is why you sometimes see utter novices speaking with supreme, unshakeable confidence on complex topics. It’s a dangerous combination of a little knowledge and a lack of metacognitive awareness.

- Detective’s Question: “On a scale of 1 to 10, how much do I really know about this topic? What are the limits of my knowledge here? Could my confidence be outpacing my expertise?” This loops back directly to the principle of intellectual humility.

The Verdict: A Lifelong Investigation

Becoming a bias detective is not a one-time project; it’s a lifelong practice. There is no graduation day where you are declared “unbiased.” The goal is not perfection but continuous improvement. It’s about being a little less wrong today than you were yesterday.

By embracing intellectual humility, you accept that you’re part of the club. By keeping a decision journal, you gather the evidence needed to see your own patterns. By practicing mindfulness, you create the space to question your automatic reactions. And by learning the signatures of common biases, you know what clues to look for.

This process can be unsettling. It requires you to challenge your own sense of certainty and to admit that your perception of reality is just that—a perception, not a perfect photograph. But the reward is immense. It leads to better decisions, more productive disagreements, deeper self-awareness, and a more profound understanding of the wonderfully flawed, endlessly fascinating machine that is the human mind. The investigation is afoot. Grab your notebook and your magnifying glass. Your first and most interesting case is you.

MagTalk Discussion

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Alright, let’s talk about some of the language we used in that article. The goal was to use rich, descriptive words that are not only powerful but also incredibly useful in everyday conversation and writing. Think of this as pulling back the curtain on the writer’s choices. Let’s dive into about ten of them.

We’ll start with a great word from the very first paragraph: pristine. We said we imagine our minds as “pristine, well-oiled machines.” Pristine means in its original condition; unspoiled. It suggests something clean, fresh, and untouched. When you buy a collector’s item “in pristine condition,” it means it’s perfect, as if it just came out of the factory. In the article, it creates this image of a mind that is pure and perfectly logical, which we then immediately contrast with reality. You can use this in so many ways. You might talk about a pristine beach that hasn’t been spoiled by tourism, or a classic car that’s in pristine shape. It’s a much more elegant way of saying “perfectly clean” or “brand new.” It carries a sense of purity.

Next up, arsenal. We described the brain as having an “arsenal of mental shortcuts.” An arsenal is a collection of weapons and military equipment. Of course, the brain doesn’t have literal weapons. Here, we’re using it metaphorically to mean a large collection of resources or tools available for a specific purpose. It’s a powerful, slightly dramatic word. You could say a skilled debater has an arsenal of arguments, or a chef has an arsenal of spices. It implies not just a collection, but a powerful, well-stocked collection ready for use. It adds a bit of flair and intensity compared to just saying “a lot of tools.”

Let’s look at the phrase lead us astray. We said that our mental shortcuts “often lead us astray.” This is a wonderful idiom. To lead someone astray means to cause them to act in a wrong or foolish way; to misguide them. It’s not just about giving wrong directions; it has a moral or judgmental undertone. A charismatic but dishonest leader can lead his followers astray. In our context, our own brains are misguiding us, tricking us into making errors in judgment. It’s a versatile phrase. You could warn a friend, “Be careful, his smooth-talking could lead you astray from your original goals.”

Then we have pervasive. We called the bias blind spot a “pervasive tendency.” Pervasive means spreading widely throughout an area or a group of people. It’s often used to describe something unwelcome or unpleasant, like a pervasive smell or a pervasive sense of gloom. By calling the bias blind spot pervasive, we’re highlighting that it’s everywhere, affecting almost everyone, and it’s hard to escape. It’s a more sophisticated word than “common” or “widespread.” You could talk about the pervasive influence of social media on modern life, for example.

Moving on, we used the word fallible. We said intellectual humility is the recognition that your knowledge is “finite and fallible.” Fallible simply means capable of making mistakes or being erroneous. Humans are fallible. Memory is fallible. It’s the opposite of infallible, which is a word often associated with popes or divine beings. Acknowledging that you are fallible is the core of intellectual humility. It’s a fantastic word for formal discussions or writing. Instead of saying, “Hey, I can be wrong,” you could say, “Of course, my analysis is based on my own fallible judgment.” It sounds more thoughtful and self-aware.

Now for a verb: underpinning. We suggested seeking out dissenting opinions to highlight the “assumptions underpinning your own beliefs.” To underpin something literally means to support it from below, like putting supports under a weak wall. Metaphorically, it means to provide the basis or foundation for an argument, claim, or belief system. It’s the core structure holding it up. What are the facts underpinning your theory? What principles underpin this company’s culture? It’s a great, analytical word that forces you to think about the foundations of an idea.

Let’s talk about colossal. We said our emotional state has a “colossal impact on our decisions.” Colossal just means extremely large or great. It’s a step up from “huge” or “massive.” It comes from the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Using it adds a sense of scale and importance. A mistake could be a colossal waste of time. A new discovery could have a colossal impact on science. It’s a word you use when you want to emphasize immense size or significance.

Here’s another great one: supercharged. We mentioned that social media has “supercharged this bias [Confirmation Bias].” A supercharger is a device on an engine that boosts its power and performance. So, to supercharge something is to make it faster, more powerful, or more effective, often dramatically so. The new software update supercharged my computer’s performance. The star player’s return supercharged the team’s morale. In the article, it paints a vivid picture of social media acting as a powerful amplifier for our natural tendencies.

Then there’s the phrase ad infinitum. Speaking of echo chambers, we said our own views are “reflected back at us ad infinitum.” This is a Latin phrase that has been fully adopted into English. It means again and again in the same way; forever. It suggests a process that is endless and often tedious or annoying. The committee debated the minor point ad infinitum without reaching a decision. It’s a more formal and forceful way of saying “endlessly” or “on and on.”

Finally, let’s look at unsettling. We concluded that this process of self-investigation can be “unsettling.” Unsettling means causing nervousness, anxiety, or disturbance. It’s that feeling you get when something is not quite right, when your sense of stability is shaken. An unsettling silence, an unsettling dream, an unsettling piece of news. It perfectly captures the feeling of questioning your own long-held beliefs. It’s not devastating, but it makes you uncomfortable. It’s a very precise emotional word that’s great for describing psychological states.

So there you have it. Ten words and phrases—pristine, arsenal, lead us astray, pervasive, fallible, underpinning, colossal, supercharged, ad infinitum, and unsettling—that add depth, precision, and a bit of style to your communication. Try to find opportunities to weave them into your own speaking and writing.

Now for our speaking section. Today’s speaking skill is about using metaphors and analogies to explain complex ideas. The article did this constantly—comparing the brain to a lazy personal assistant, bias to fingerprints at a crime scene, or social media to a supercharger. Why? Because complex, abstract ideas like “cognitive bias” can be hard to grasp. A good metaphor connects that abstract idea to something concrete and familiar, making it instantly understandable and memorable. Explaining the Dunning-Kruger Effect is tough. But saying it’s when someone is “too incompetent to recognize their own incompetence” and is standing on “Mount Stupid” (a popular visual metaphor for it) makes it stick.

Your challenge is this: Pick one cognitive bias—it could be one from the article like Confirmation Bias or the Anchoring Effect, or you can look up another one like the Bandwagon Effect or Negativity Bias. Your task is not just to define it. Your task is to explain it to someone using an original metaphor or analogy. Record yourself doing it. You could start with, “So, I was learning about this thing called [Bias Name], and the best way I can describe it is…” Try to make your metaphor visual and relatable. For example, for Confirmation Bias, you could say, “It’s like you’re a detective who already decided who the culprit is, and now you’re just walking around the crime scene only picking up the clues that prove you’re right, and ignoring everything else.” See? It creates a mini-story. This exercise will not only test your understanding of the concept but will dramatically improve your ability to communicate complex topics in an engaging and persuasive way. It forces you to be creative and clear, which is the heart of great speaking. Give it a shot.

Grammar and Writing

Welcome to the part of our journey where we shift from understanding ideas to crafting them on the page. Good writing is clear thinking made visible, and nowhere is that more true than when writing about our own internal worlds. Today, we’re going to tackle a writing challenge that asks you to be a true bias detective and report your findings.

The Writing Challenge:

Write a short personal narrative or reflective essay (around 500-750 words) about a time when you realized you were acting under the influence of a specific cognitive bias. The goal is not to judge yourself, but to explore the situation with the curiosity of a detective. Your narrative should:

- Set the Scene: Describe the situation and the decision you had to make.

- Detail Your Initial Thought Process: Reconstruct what you were thinking and feeling at the time. What seemed logical or obvious to you then?

- The “Aha!” Moment: Describe the moment of realization. What happened or what information came to light that made you question your initial thinking and spot the bias at play?

- Reflection: Conclude by reflecting on the experience. What did you learn about your own mind? How has this awareness changed how you approach similar situations now?

This is a powerful exercise in self-awareness, but it can be tricky to write well. Let’s break down the grammar and writing techniques that will make your story compelling and clear.

Grammar Spotlight: Mastering the Past Tense and Temporal Clauses

Since you’re writing a narrative about a past event, your primary tool will be the past tense. But to make your story dynamic, you need to show the relationship between different moments in time. This is where temporal clauses and a variety of past tenses come in.

- Simple Past: This is your workhorse. It describes completed actions in the past. “I accepted the job offer. I believed it was the right choice.“

- Past Continuous: This sets the scene and describes ongoing actions in the past that were interrupted. It’s great for building context. “I was scrolling through my news feed when I saw the article that changed my mind.” The scrolling was ongoing; seeing the article was a single event.

- Past Perfect: This is your “time machine” tense. It describes an action that happened before another past action. It’s crucial for showing the sequence of events and thoughts. “By the time my friend presented the counter-evidence, I had already convinced myself I was right.” The convincing happened before the presentation of evidence.

- Past Perfect Continuous: This is for describing an ongoing action that was happening before another past event. It emphasizes duration. “I had been ignoring the warning signs for weeks before the project finally collapsed.“

Temporal clauses are phrases that tell us when something is happening, using words like when, while, before, after, as soon as, until, by the time. Mixing these with different tenses creates a sophisticated narrative flow.

Example:

- Simple: I bought the stock. My friend advised against it. (A bit choppy)

- Better, with temporal clauses and varied tenses: Even though my friend had warned me about the risks, I bought the stock anyway. While I was clicking ‘confirm purchase,’ I felt a rush of excitement, completely ignoring the sunk cost fallacy that had been clouding my judgment.

Notice how the tenses and clauses create a rich timeline of events and mental states.

Writing Technique: “Show, Don’t Tell” with Internal Monologue

The prompt asks you to reconstruct your thought process. The least effective way to do this is to “tell” the reader what you were thinking.

- Telling: “I was exhibiting confirmation bias. I only wanted to see evidence that supported my initial decision to buy the expensive camera.”

- Showing: “This new camera was the one. ‘The reviews are amazing,’ I muttered to myself, quickly scrolling past a forum thread titled ‘Serious Overheating Issues.’ That was probably just a faulty batch. I clicked on another glowing video review. See? This guy loves it. He’s a professional. He knows what he’s talking about. The negative voices were just outliers, bitter amateurs who didn’t know how to use it properly.”

The “showing” example puts the reader directly inside your head. It uses internal monologue (your direct thoughts, often in quotes or italics) and action to reveal the bias without explicitly naming it until the reflection part of the essay. This is far more engaging and allows the reader to play detective alongside you.

Structuring Your Narrative for Impact

A good story needs a clear arc. For this challenge, consider this structure:

- The Hook (The Setup): Start in the middle of the action or with a statement that establishes the stakes.

- Example: “The ‘Buy Now’ button seemed to pulse with a light of its own. All that stood between me and a professional-grade podcasting setup was a single click and a colossal dent in my savings.”

- The Rising Action (The Justification): This is where you build the case for your biased decision. Use the “showing” technique and internal monologue to detail your flawed reasoning. This is where you describe how you fell for the anchoring effect based on the initial high price, or how you looked for information that confirmed your desire to buy it.

- The Climax (The “Aha!” Moment): This is the turning point. It could be a conversation, a piece of data you can no longer ignore, or a moment of quiet reflection triggered by something unexpected. Make this moment clear and impactful.

- Example: “It wasn’t until my credit card statement arrived a month later, and I saw the charge sitting there next to my rent payment, that the fog began to clear. I hadn’t used the camera once. I looked over at it, collecting dust, and the reviewer’s excited voice in my memory was replaced by a quiet, unsettling question: ‘Did you buy the camera you needed, or the camera you wanted everyone to think you owned?'”

- The Falling Action & Resolution (The Reflection): Now you can explicitly name the bias. Connect the dots for your reader. What did you learn? How has this experience equipped you to be a better thinker? This is where you “tell” what you’ve “shown.” Conclude with a powerful takeaway about self-awareness or intellectual humility.

By combining precise grammatical control over time, the narrative technique of showing over telling, and a clear story structure, you can turn a simple reflection into a compelling and insightful piece of writing. Good luck, detective.

Vocabulary Quiz

Let’s Discuss

These questions are designed to get you thinking more deeply about the role of bias in your own life and in the world around you. There are no right or wrong answers, only opportunities for reflection and discussion. Share your thoughts in the comments!

- The Bias You See Most Often: Which cognitive bias from the article (or one you know of) do you notice most frequently in others—in conversations, on social media, or in the news?

Dive Deeper: Don’t just name it. Give a recent, specific (but anonymous!) example. Why do you think that particular bias is so common in today’s world? Is it amplified by technology, politics, or our culture? Now, turn the lens on yourself: can you think of a time when you might have done the exact same thing? - The “Intellectual Humility” Challenge: The article suggests that admitting “I might be wrong” is a superpower. When was the last time you changed your mind about something important? What did it take to make you switch your view?

Dive Deeper: What was the feeling associated with that change? Was it liberating? Unsettling? Difficult? Do you think our society rewards people for changing their minds, or does it often view it as a sign of weakness or “flip-flopping”? How could we create a culture that better encourages intellectual humility? - Journaling Your Decisions: Have you ever kept a decision journal or something similar? If so, what was the most surprising pattern you discovered about yourself? If you haven’t, what is one major decision from your past that you would want to analyze with this method?

Dive Deeper: Reconstruct the decision now. What were you thinking and feeling? What were the variables you considered important then? What do you now realize you missed? What bias (Hindsight Bias, Planning Fallacy, etc.) might be coloring your memory of that event right now? - The Toughest Bias to Admit: For many, the Dunning-Kruger effect is a tough pill to swallow—no one wants to think they are overestimating their own abilities. If you had to honestly assess yourself, in what area of your life might you be most susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect? (e.g., driving ability, knowledge of politics, your professional skills).

Dive Deeper: Why is this particular bias so hard to spot in ourselves? It requires us to know the limits of our own knowledge. What steps could someone take to get a more accurate assessment of their skills in a particular area, moving from “unskilled and unaware” to “skilled and aware”? - Bias in the “Real World”: How can an understanding of cognitive biases help us in our professional lives or personal relationships? Share an example of how recognizing a bias (in yourself or someone else) could de-escalate a conflict, lead to a better team decision, or improve communication with a loved one.

Dive Deeper: Consider a typical workplace disagreement or a family argument. How might biases like Confirmation Bias (only hearing what supports your side) or the Fundamental Attribution Error (attributing others’ actions to their character, but your own to the situation) make things worse? How would a “bias detective” approach that conversation differently?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

Hello there. It’s great that we’ve spent so much time digging into the personal toolkit for spotting our own biases. That internal work is absolutely foundational. But if we stop there, we miss half the picture. I want to shed some light on how these individual glitches in our thinking scale up and create massive, society-level effects, and introduce a concept we didn’t touch on much: Systemic Bias.

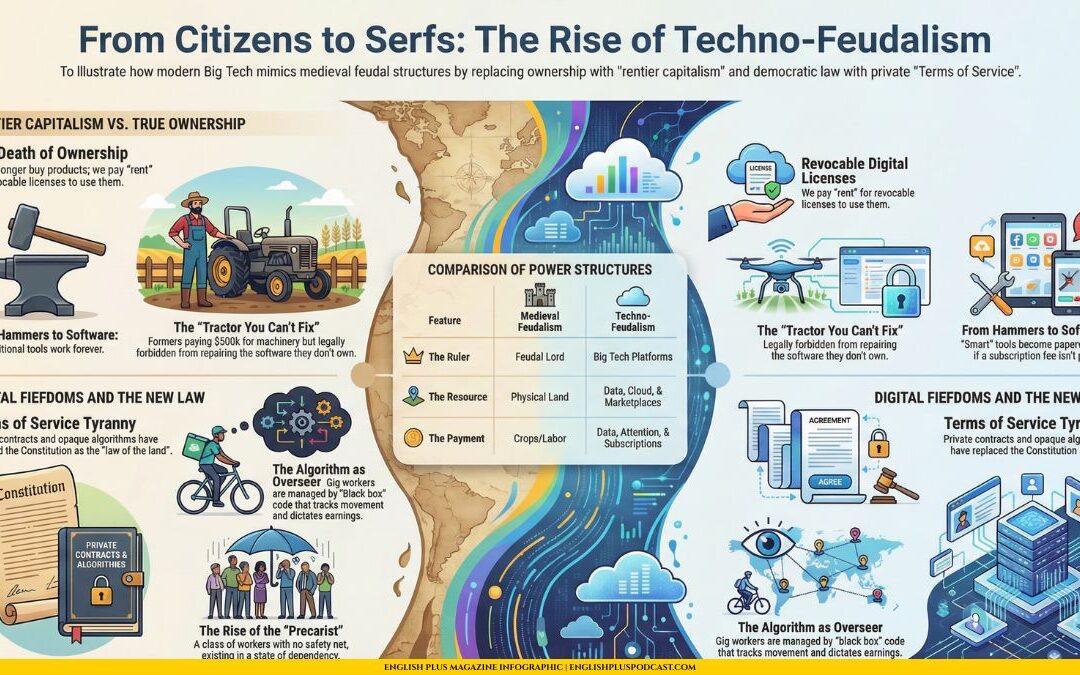

The article focused on you, the individual, becoming a detective of your own mind. That’s metacognition. But what happens when millions of individual, biased minds come together to build institutions, laws, and cultures? The biases don’t just add up; they multiply. They become embedded in the very structure of our world. This is systemic bias. It’s the cognitive bias of the group, baked into the system itself.

Let’s take a bias we discussed: the Availability Heuristic. That’s our tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events that are more easily recalled in memory, which are often recent, frequent, or emotionally charged. On an individual level, this might mean you’re more afraid of flying than driving because plane crashes are vivid, dramatic news stories, even though driving is statistically far more dangerous.

Now, how does this scale up? Media outlets, knowing that dramatic and scary stories get more clicks and views (playing on our availability heuristic), will disproportionately cover certain types of crime over others. For example, stories about stranger abductions are emotionally potent and get tons of coverage. This makes the event “available” in our collective consciousness. As a result, society might pour immense resources into preventing this statistically rare event, while perhaps underfunding responses to more common but less “available” dangers like domestic violence or malnutrition. The bias is no longer just in your head; it has shaped public policy and resource allocation. It’s become systemic.

Another example is Implicit Association. This is a close cousin of many biases we know, referring to the unconscious attributions we make about certain social groups. An individual might unconsciously associate certain ethnicities with certain traits, or men with “career” and women with “family.” They might be a good person who consciously rejects stereotypes. But their “System 1” thinking, shaped by decades of cultural exposure, still makes those lightning-fast, biased connections.

Now, let’s scale that up. Imagine a company full of hiring managers who all have a slight implicit bias associating men with leadership qualities. No single manager is a blatant sexist. They all believe they are hiring based on merit. But when faced with two equally qualified candidates, that tiny, unconscious nudge makes them feel the male candidate is just a “better fit” or has more “leadership potential.” Over hundreds of hiring decisions, this results in a company whose leadership is overwhelmingly male. No single person intended for this to happen. It’s a systemic outcome of a widely distributed, subtle, individual bias. The problem is now in the company’s DNA.

So, the perspective I want to add is this: becoming a bias detective for your own mind is crucial. But the “expert level” of this work is to become a systemic bias detective. It’s to learn to see how these patterns are reflected in our institutions. When you look at disparities in healthcare, criminal justice, or corporate boardrooms, don’t just look for a single “bad apple.” Ask yourself: “What collection of common human biases could, over time, create a system that produces this outcome?”

This shifts the focus from blame to diagnosis. It’s less about finding villains and more about understanding the architecture of error. And it suggests that the solutions aren’t just about telling individuals to “think better,” but about redesigning the systems themselves to be more bias-resistant—for example, by using blind resume reviews in hiring or establishing clear, objective criteria for medical diagnoses.

So, as you continue your investigation, expand your jurisdiction. Look for the clues not just in your own head, but in the blueprints of the world around you.

0 Comments