Audio Primer

Introduction

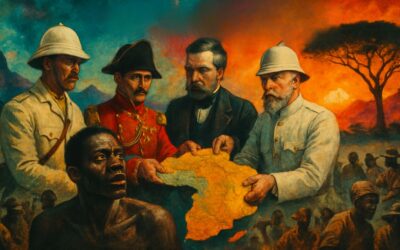

When we talk about global art and historical artifacts, the conversation can often get stuck in the past, focusing on blame and ownership disputes. But a new, more productive conversation is emerging. This new dialogue isn’t about blame; it’s about understanding. It’s not just about what happened, but about what we can and should do now.

How do we ethically care for our shared history? How can technology make heritage accessible to everyone? What does it mean to return an object to its home?

To participate in this vital, forward-looking discussion, we need the right vocabulary. This quiz is designed as a learning tool to teach you the constructive language of cultural exchange. By understanding terms like repatriation, provenance, and conservation, you’ll be empowered to move beyond the old arguments and help build a future where our collective heritage can be celebrated, preserved, and shared with respect for all. This isn’t just a test; it’s your first step into a more hopeful and collaborative way of thinking about art.

Learning Quiz

This is a learning quiz from English Plus Podcast, in which, you will be able to learn from your mistakes as much as you will learn from the answers you get right because we have added feedback for every single option in the quiz, and to help you choose the right answer if you’re not sure, there are also hints for every single option for every question. So, there’s learning all around this quiz, you can hardly call it quiz anymore! It’s a learning quiz from English Plus Podcast.

Quiz Takeaways | Building Bridges, Not Walls

Hello, and welcome! If you’ve just finished the quiz, congratulations. You’ve just taken a huge step toward understanding one of the most important and exciting conversations happening in the world of art and history today.

For a long time, the discussion around cultural artifacts, especially those that have traveled far from their homes, was all about conflict. It was about who owned what, who took what, and who was to blame. Honestly, that kind of conversation doesn’t get us very far. It builds walls.

What we’ve explored today is a new vocabulary. It’s the language of a more positive, productive, and forward-looking discussion. This isn’t about ignoring the past; it’s about understanding it honestly so we can build a better future. It’s a vocabulary built on concepts like respect, care, and collaboration. This is the language of bridge-building.

So, let’s break down what we’ve learned.

The most important, all-encompassing idea is cultural heritage. This is a beautiful term because it’s so much bigger than just “art.” It includes everything that makes a culture unique. We learned to divide it into two categories. First, there’s tangible heritage—the physical stuff. This is what you typically see in a museum: a statue, a temple, an ancient book, a painting. You can touch it. But just as important, and often more fragile, is intangible heritage. This is the “living” culture: the traditions, the music, the dances, the languages, the oral stories, and the craft-making skills that are passed down from one generation to the next. You can’t put a language in a display case, but if it disappears, we’ve lost a piece of human heritage forever.

So, once we agree that all this heritage is valuable, the next question is: How do we interact with it? This starts with understanding an object’s life story. In the museum world, this is called provenance. Think of it as an object’s biography or its resume. Where was it born? Who made it? Who owned it first? Where did it go next? Was it sold? Was it given as a gift? Was it stolen?

This is where provenance research and due diligence come in. These are the tools of the modern, ethical museum. Before acquiring any new object, a museum must do its homework. It must conduct due diligence to trace that provenance, ensuring the object wasn’t looted during a war or illegally excavated and smuggled out of its home country. This guarantees the object’s authenticity—that it’s the real deal—and that the museum is acquiring it ethically.

Now, let’s say a museum is the ethical guardian of an object. What is its core responsibility? That responsibility is summed up in one word: stewardship. This is the philosophy that a museum doesn’t “own” its collection in the way you or I own a T-shirt. Instead, it holds these objects in the public trust, with a profound ethical duty to care for them for all future generations.

This “care” part is a science. And here, we learned a crucial distinction: conservation versus restoration. For centuries, the goal was restoration: to make an old object look brand new. A restorer might repaint a faded fresco or replace a statue’s missing arm. The problem is, this can erase the object’s true history. The modern, more ethical approach is conservation. A conservator’s job is not to make it look new, but to make it last. They scientifically stabilize the object—stopping paint from flaking, preventing a manuscript from crumbling—to preserve its current, authentic state.

Of course, in the 21st century, we have a powerful new tool for this: digital preservation. By using high-resolution 3D scanning and photography, we can create a perfect digital “replica” of an object. This is a game-changer. It means that if the original—like a historic site—is ever damaged by war or natural disaster, we still have a perfect record. But even more importantly, it makes heritage accessible to everyone on Earth. A student in another country can now virtually hold and study an artifact that they would never have been able to see in person.

This brings us to the topic that is at the very center of the modern debate: the journey of objects. We learned the term repatriation, which comes from “patria,” or homeland. This is the act of returning a cultural artifact to its country or community of origin. It is not about blame. It is about acknowledging that some objects have a cultural, spiritual, and historical significance that is most powerful in their original context. Closely related is restitution, which carries the stronger moral weight of returning something that was confirmed to have been looted or stolen. This is not about emptying all museums; it’s about having open, respectful dialogues to correct historical wrongs.

And this is where we find the way forward. The future isn’t about every country holding onto its own stuff and never sharing. The future is about cultural exchange. This is the positive, collaborative process where institutions loan artifacts and, just as importantly, knowledge to one another. It’s a two-way street. A museum in Paris can share its collection with an audience in Lagos, and the museum in Lagos can share its heritage with the audience in Paris. This is how we use art to build those bridges of mutual understanding.

Finally, we learned some of the “business” terms that make all this work. We learned about curation—the storyteller’s job of researching, selecting, and interpreting objects for an exhibit. We learned about the formal processes of accession (adding an object to the collection) and deaccession (formally removing one).

When you put all these words together—provenance, stewardship, conservation, digital preservation, repatriation, and cultural exchange—you get the framework for museum ethics. This is the moral code that guides modern institutions.

You now have the vocabulary to be partt of this new, constructive, and essential conversation. You can see how these ideas all fit together to create a future where our shared human heritage isn’t a source of conflict, but a tool for connection. Thank you for learning.

0 Comments