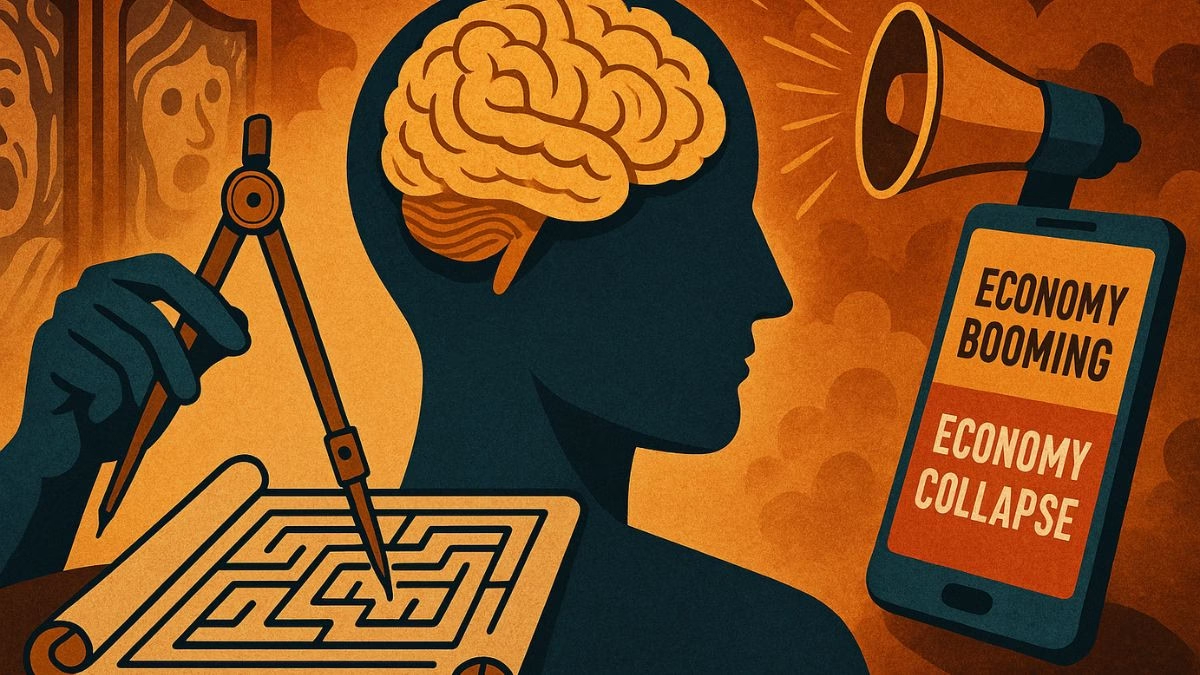

Have you ever found yourself in the middle of a digital rabbit hole at one in the morning? You started by searching for a simple recipe, and now, somehow, you’re watching a video explaining why everything you thought you knew about ancient history is a lie, presented by a guy with a very confident voice and some questionable graphics. Do you ever scroll through your newsfeed and feel a kind of mental whiplash? One post, from a source you trust, says a new health trend is a miracle. The very next post, from another source you also trust, calls it dangerous nonsense. One headline screams that the economy is booming; another warns of an imminent collapse.

It feels a little like being lost in a massive, digital funhouse, doesn’t it? One with a million shouting voices, distorting mirrors, and hidden trapdoors. It can be overwhelming. It can be exhausting. And it can make you want to just tune it all out.

But what if I told you there’s a way to navigate this funhouse? What if there was a skill, a kind of internal compass, that could help you find the true path, spot the illusions, and walk out with your sanity intact? What if the most important skill for success, and frankly, for survival in the 21st century isn’t learning to code, or mastering a new language, but simply learning how to think with clarity, discipline, and purpose?

That skill is called critical thinking. And I know, I know, the name itself sounds a bit… critical. It sounds negative, like the whole point is to just poke holes in things and be cynical. But that’s one of the first and biggest misconceptions we need to clear up. This isn’t about becoming a professional critic or that person at a party who constantly says, “Well, actually…” to ruin everyone’s good time. This is about something much deeper, much more powerful. It’s about building a toolkit for your own mind. It’s about an intellectual renaissance, a personal reawakening of our ability to reason in an age that often seems to reward the opposite.

In this episode, we’re going to answer those big questions. We’re going to pull back the curtain and discover what critical thinking really is—beyond the buzzwords and the misconceptions. We’ll explore its fundamental components, the very pillars that hold up a thoughtful mind. And most importantly, we’re going to make the case for why right now, in this age of rampant misinformation, social media echo chambers, and the dawn of powerful artificial intelligence, this skill has transformed from a ‘nice-to-have’ academic exercise into an essential guide for navigating our wild, modern world.

Deconstructing the Definition: More Than Just Being Critical

So, let’s start by tearing down that old, rickety definition of critical thinking. For a lot of people, the word “critical” is synonymous with “negative.” A film critic points out a movie’s flaws. Your boss gives you critical feedback on a project. It’s all about finding what’s wrong. But in the context of critical thinking, that’s only a tiny, tiny fraction of the picture. True critical thinking isn’t inherently negative or positive; it is inherently constructive. It’s the process of building a reliable understanding of the world.

Think of yourself as a master watchmaker. A bad watchmaker might just smash a broken watch with a hammer and say, “Yep, it’s broken.” That’s cynicism. A slightly better one might point out a scratch on the glass. That’s simple criticism. But a master watchmaker—a critical thinker—doesn’t just criticize. They carefully, methodically, take the watch apart piece by piece. They examine each tiny gear, each spring, each cog. They look at how they all fit together. They assess the quality of each component. Then, with a full understanding of the system, they can identify the precise point of failure, fix it, and put the watch back together so it works better than before. That is the essence of critical thinking.

It is the disciplined art of three key actions: analysis, evaluation, and inference. Let’s break those down.

First, there’s Analysis. This is the “taking the watch apart” phase. When you’re presented with a piece of information—a news article, a political argument, an advertisement—analysis is the skill of deconstructing it into its core components. It means asking questions like: What is the main point being made here? What are the key arguments used to support that point? What evidence is being presented? Are there any assumptions being made that aren’t explicitly stated? You’re not judging anything yet; you’re just laying out all the pieces on the table so you can see them clearly. You’re creating a map of the argument.

Let’s take a simple, common example. You see a flashy online ad for a new “super-concentrated energy drink.” The ad shows vibrant, happy people acing their exams and winning sports games. The text promises “all-day energy with no crash, thanks to our proprietary blend of exotic herbs.” Analysis means you mentally pause and break it down. The main point is “buy our drink.” The supporting arguments are “it will give you energy” and “it has no crash.” The evidence presented is the imagery of successful people and the mention of a “proprietary blend.” The unstated assumption is that these happy people are happy because of the drink, and that “proprietary” and “exotic” automatically mean effective and safe.

See? No judgment yet. We’ve just taken the ad apart and looked at its guts.

Next comes Evaluation. Now that all the pieces are on the table, we start acting like a quality control inspector. This is where we judge the worth of each component. Is the evidence strong or weak? Is the source credible? Is the reasoning logical or flawed?

Back to our energy drink. Let’s evaluate the pieces. The evidence of happy people is an emotional appeal, not factual data. It’s a classic marketing trick called an “association fallacy.” The claim of “no crash” is a big one; where’s the proof? Are there studies? Or is it just a slogan? And that phrase, “proprietary blend of exotic herbs”—that sounds impressive, but it’s actually a way to avoid telling you what’s in it or how much. It’s a red flag, not a selling point. The source is a company trying to sell you something, so their bias is clear: they have a financial incentive to make their product sound amazing. Evaluation is the process of assigning a value of “strong” or “weak,” “reliable” or “unreliable” to each piece you’ve laid out.Finally, we have Inference. This is the grand finale. It’s the act of reassembling all those evaluated pieces into a reasoned judgment or conclusion. Based on your analysis and your evaluation, what is the most logical thing to believe?

So, with our energy drink ad: we’ve analyzed its claims and evaluated its evidence. Our inference would be something like this: “The advertisement relies on emotional appeals rather than scientific evidence. Its claims are unsubstantiated, and it uses vague language to hide a lack of transparency. Therefore, I cannot conclude that this drink is effective or safe based on this ad alone. I should be skeptical.”

And there it is. Analysis, Evaluation, Inference. You’ve just performed a full critical thinking workout. You didn’t just passively consume the information; you actively engaged with it. You didn’t just criticize it by saying “that’s dumb.” You constructed a reasoned, defensible conclusion. That’s the difference. And it’s a difference that can save you time, money, and from believing a lot of nonsense.

The Pillars of a Thinking Mind

If analysis, evaluation, and inference are the actions of critical thinking, then what are the core mindsets or principles that allow us to perform those actions effectively? I like to think of them as the three pillars that hold up the entire structure of a critical mind. Without them, the whole thing collapses. These pillars are Logic, Humility, and Skepticism.

Let’s start with the first pillar: Logic and Reasoning. This is the architectural blueprint of a strong argument. Logic is the set of rules that governs how we get from A to B in our thinking. It’s what allows us to say, “If this is true, and that is true, then this third thing must also be true.” It’s about cause and effect, about coherent structure. When an argument is “illogical,” it means the pieces don’t fit together correctly. The conclusions don’t follow from the evidence.

There are two main types of reasoning you use all the time, probably without thinking about it. The first is deductive reasoning. This is the classic Sherlock Holmes approach. You start with a general rule or premise that you know to be true, and you apply it to a specific situation to reach a guaranteed conclusion. The famous example is: The general premise is “All men are mortal.” The specific case is “Socrates is a man.” The deductive conclusion is “Therefore, Socrates is mortal.” If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. It’s a top-down process.

The second type is inductive reasoning. This is the engine of scientific discovery. It’s the opposite of deduction; it’s a bottom-up process. You start with specific observations and you try to form a general principle or theory. For example, you see a thousand swans, and every single one is white. You might form an inductive conclusion: “All swans are white.” Now, is this conclusion guaranteed to be true like the Socrates example? No. It’s based on probability. It’s strong, but it’s not foolproof. The moment someone finds a black swan in Australia—which they did—your theory is proven incomplete. Most of what we “know” about the world, from gravity to medicine, is built on powerful inductive reasoning—countless observations all pointing to the same general conclusion. A good critical thinker understands which type of reasoning is being used and how certain the conclusion can be.

The second pillar is, in my opinion, the most difficult and the most important: Objectivity and Intellectual Humility. This is the pillar that forces us to turn the spotlight on ourselves. Being objective means striving to see things as they are, without being clouded by our own personal feelings, biases, or preconceived notions. It’s about separating fact from feeling. But let’s be honest, perfect objectivity is probably impossible. We are all walking bundles of biases and experiences.

That’s where intellectual humility comes in. If objectivity is the goal, intellectual humility is the path. It is the single most powerful trait a thinker can possess. It is the profound, gut-level acceptance that you might be wrong. It’s the understanding that your knowledge is finite and that your current beliefs are subject to change in the face of better evidence. It’s the opposite of that dogmatic, unshakable certainty we see so often. The person screaming the loudest on social media is often the least intellectually humble. They’ve confused confidence with correctness.

A truly critical thinker embraces the phrase, “I don’t know.” They are more interested in what is true than in being right. This is a superpower. It allows you to update your beliefs, to learn from your mistakes, and to actually grow as a person. Without it, you’re just stuck in a loop, endlessly reinforcing what you already think you know.

The third and final pillar is a dynamic duo: Curiosity and Skepticism. These two work together like a brilliant detective team. Curiosity is the engine; it’s the insatiable desire to know more. It’s the part of you that asks, “Why?” and “What if?” and “How does that work?” A curious person doesn’t just accept a headline at face value; they want to know the story behind the story. Curiosity is what drives you to click the link, to find the original source, to learn about the topic. Without curiosity, thinking is just a chore.

But curiosity alone can be gullible. It can lead you down any and every rabbit hole. That’s why it needs a partner: skepticism. Healthy skepticism is not the same as cynicism. A cynic believes nothing and assumes everyone has bad intentions. A skeptic, on the other hand, just wants to see the evidence. The skeptic’s motto is, “That’s interesting. Show me the proof.” It’s a methodical, evidence-based doubt. It’s the part of you that asks, “How do you know that?” and “Is that source reliable?” and “Are there other possible explanations?”

Think of it this way: Curiosity is the detective who says, “I have a new lead in the case!” Skepticism is the partner who says, “Great. Let’s verify it before we go breaking down any doors.” You need both to solve the mystery. Curiosity provides the energy and the leads; skepticism provides the discipline and the rigor.

So there you have it. The three pillars: Logic and Reasoning as your blueprint, Intellectual Humility as your foundation, and the team of Curiosity and Skepticism as your investigators. With these in place, your ability to analyze, evaluate, and infer becomes rock solid.

Why Now? The Urgency of a Critical Thinking Renaissance

Okay, so we’ve established what critical thinking is. It’s a structured process, a set of principles. It’s been valuable for centuries, from Socrates to the Enlightenment. But why am I calling this a “renaissance”? Why the sense of urgency right now, on October 5th, 2025? Because our modern world has produced a perfect storm of challenges that specifically target and exploit our weaknesses in thinking. I see three great tsunamis of our time, and critical thinking is the high ground we need to reach to survive them.

The first is the Tsunami of Misinformation. We no longer live in an age of information scarcity; we live in an age of information overload. We are drowning in it. There is more content uploaded to the internet in a single day than you could consume in a hundred lifetimes. And within that deluge is a deliberate and ever-growing flood of misinformation, disinformation, and simple, low-quality junk.

The platforms we use every day, like social media, are not designed to prioritize truth. They are designed to prioritize engagement. Their algorithms learn what you like, what you fear, what makes you angry, and then they feed you more of it, because that’s what keeps you scrolling. This creates personalized realities for each of us, known as filter bubbles and echo chambers. Your reality starts to look different from your neighbor’s reality, not because the world is different, but because your information feeds are.

Think about it this way: a few decades ago, if a man stood on a street corner shouting conspiracy theories, most people would just walk by. He had no credibility and no reach. Today, that same man can create a slick YouTube video. The algorithm, noticing that his video is provocative and gets a lot of angry comments and shares, can push it to millions of people. It can place his video right next to one from a respected university professor, and on the screen, they both look equally legitimate. The old gatekeepers of information—librarians, editors, journalists—have been replaced by algorithms that value clicks over credibility. In this environment, the responsibility to sort fact from fiction has been outsourced from the institution to the individual. That’s you. Without critical thinking, you’re navigating this tsunami on a pool noodle.

The second great wave is the Rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Tools like ChatGPT and others have exploded into our lives, and they are miraculous. They can write code, compose poetry, explain complex topics, and draft emails. They are incredibly powerful assistants. But they have a dark side. These AIs are designed to generate plausible-sounding text. They are not designed to tell the truth. They do not know things; they are pattern-recognition machines that predict the next most likely word in a sentence.This leads to a phenomenon called “AI hallucination,” where the AI will state something with complete, unwavering confidence that is entirely, demonstrably false. It will invent historical events, make up scientific studies, and create fake quotes. And because it sounds so authoritative, it’s incredibly easy to believe.

This changes the game. We are rapidly moving from a world where our primary intellectual task was creating information to a world where our primary task will be curating and validating information generated by machines. Your job is no longer just to write the report; it’s to critically evaluate the report the AI wrote for you. Is it accurate? Is it biased? Did it invent its sources? The skill of the future isn’t just knowing how to ask the AI a question; it’s having the critical thinking skills to judge the quality of its answer. AI can be a phenomenal partner for a critical thinker, but it can be a devastating crutch for a passive one.

The third and final tsunami is the Overwhelming Complexity of Modern Problems. Think about the major issues we face as a global community: climate change, economic inequality, political polarization, public health crises. These are not simple, straightforward problems. They are “wicked problems”—intricate systems with countless interconnected variables. They don’t have easy answers, and anyone who tells you they do is either a fool or a liar.

To even begin to understand these issues, you have to be able to hold multiple, often contradictory, ideas in your head at the same time. You have to be able to analyze complex data, evaluate the arguments of different experts, and infer potential consequences of various actions. The temptation, when faced with such overwhelming complexity, is to retreat into simplistic, black-and-white thinking. To pick a side, join a tribe, and just parrot their talking points. It’s easier. It’s more comfortable. But it solves nothing.

Critical thinking is the antidote to this intellectual laziness. It gives you the mental scaffolding to grapple with complexity. It allows you to break down a massive, intimidating problem into smaller, more manageable parts. It helps you appreciate nuance, weigh trade-offs, and resist the siren song of the easy answer. It is the tool we need to have any hope of collaboratively and intelligently solving the great challenges of our time.

The Path Forward

So, we stand at a crossroads. We’re faced with these three great waves: a tsunami of misinformation designed to confuse us, the rise of a powerful AI designed to assist but capable of misleading us, and a world of complex problems that demand our sharpest thinking. It sounds daunting, I know.

But it’s also an opportunity. It’s an invitation to engage in a personal renaissance of the mind. It’s a call to move beyond being passive consumers of information and to become active, discerning, and conscious participants in our own understanding. Critical thinking isn’t some esoteric academic subject. It is a fundamental life skill. It is our best defense against manipulation, our most powerful tool for self-improvement, and our most reliable compass for navigating the future. It’s how we take back control. It’s how we learn to own our own minds.

Outro

We’ve covered a lot of ground today. We’ve redefined critical thinking as a constructive process of analysis, evaluation, and inference. We’ve explored the pillars of logic, humility, and skepticism that support it. And we’ve laid out the urgent case for why this renaissance is needed now more than ever.

This is the ‘what’ and the ‘why’. But this is just the beginning of our journey. Now that we understand the landscape, we need to learn how to spot the traps. How do advertisers, politicians, and influencers use the very nature of language to bypass our critical thinking defenses? What are the dark arts of persuasion, the sneaky tricks of rhetoric that are used against you in every medium, every single day?

In our next episode, we’re going on the offensive. We’re going to arm you with knowledge. We’re diving deep into the fascinating world of logical fallacies—the common errors in reasoning that make bad arguments sound good. We’re going to learn how to spot a straw man, an ad hominem, and a slippery slope from a mile away. You are going to learn the language of logic, so you can start to see the code, the matrix, behind the messages that bombard you every day. It’s going to be your first lesson in intellectual self-defense. You won’t want to miss it.

0 Comments