Become a “Bias Hacker” 🛠️

You’ve learned to spot cognitive biases in the wild, but are you ready for the next level? Welcome to the “Bias Hacker” quiz, where we move from theory to practical application. Knowing what a bias is is one thing; knowing how to use that knowledge is a superpower.

In this quiz, you won’t be just defining terms. You’ll be put in the driver’s seat—as a marketer, a manager, a friend, or even as your own life coach. For each scenario, your mission is to choose the strategy that correctly applies a specific psychological principle to achieve a goal. The benefit? You’ll develop a powerful toolkit for designing more persuasive messages, making better decisions, and even improving your own productivity. This is where psychology gets practical. Let’s start hacking!

Learning Quiz

This is a learning quiz from English Plus Podcast, in which, you will be able to learn from your mistakes as much as you will learn from the answers you get right because we have added feedback for every single option in the quiz, and to help you choose the right answer if you’re not sure, there are also hints for every single option for every question. So, there’s learning all around this quiz, you can hardly call it quiz anymore! It’s a learning quiz from English Plus Podcast.

Quiz Takeaways | The Choice Architect’s Handbook: Using Psychology for Good

Congratulations on finishing the quiz! You’ve just stepped into the role of a “choice architect”—someone who organizes the context in which people make decisions. What you’ve seen is that the way a choice is presented can have a massive impact on the final outcome. This isn’t magic; it’s applied psychology. By understanding these deep-seated biases, we can design better experiences, create more persuasive messages, and even nudge ourselves toward our own goals. Let’s break down what we’ve learned.

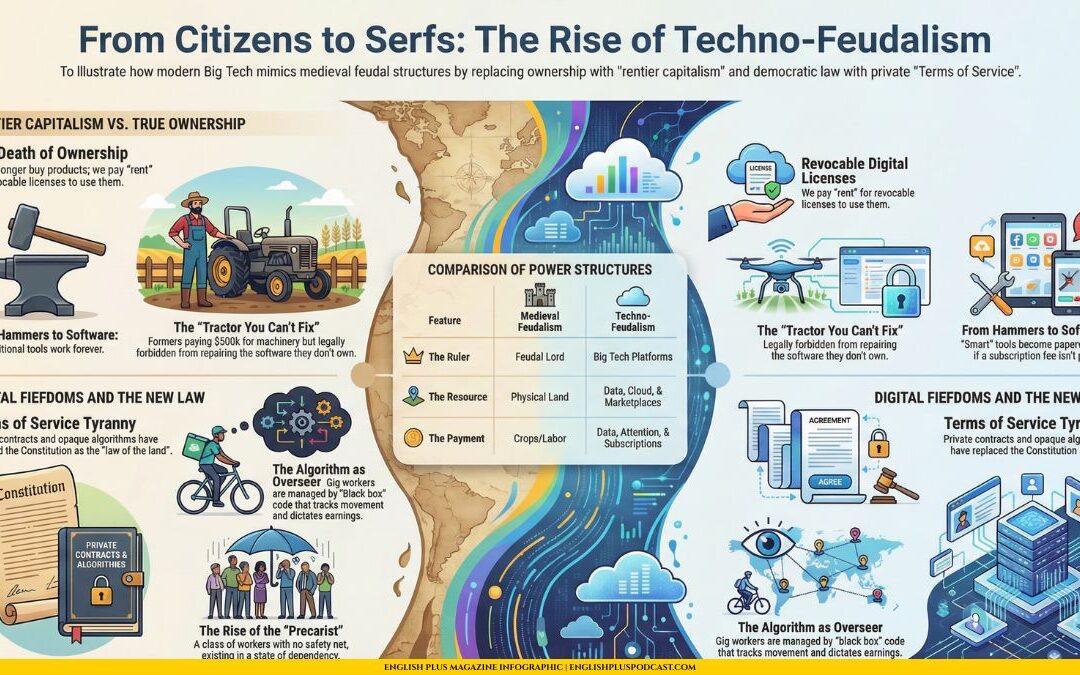

A huge part of choice architecture is about persuasion in business and marketing. This is where some of the most famous biases are put to work. We saw how Anchoring can influence how much people are willing to donate or pay by setting a high initial reference point. We saw how the Decoy Effect can make a “target” product seem like an obvious bargain by introducing a slightly inferior third option. These tactics work because our brains don’t evaluate things in a vacuum; we are constantly making comparisons. Businesses also powerfully leverage our fear of losing things. Loss Aversion, the principle that the pain of a loss is stronger than the pleasure of an equal gain, is why “Don’t lose your benefits!” is more persuasive than “Get new benefits!” Similarly, creating Scarcity with “limited editions” or “limited time offers” makes a product seem more valuable because we fear the loss of the opportunity to get it.

But it’s not all about selling things. These principles are woven into the fabric of our social lives. The principle of Reciprocity, for instance, is the invisible engine of social cooperation. Doing a small favor for a friend, like buying them a pizza, creates a powerful, non-transactional desire for them to help you in return. We also saw how you can manage perceptions. The Halo Effect shows us the immense power of a positive first impression, creating a “halo” that makes people view your subsequent actions more favorably. You can even increase your likability by making a small mistake—the Pratfall Effect—which humanizes you and makes you seem more relatable. And if you just want to build a sense of trust and familiarity, whether for a new brand or a new friendship, the Mere-Exposure Effect shows that simple, repeated exposure is a surprisingly powerful tool.

Perhaps the most empowering part of this toolkit is the ability to use these biases on yourself to achieve your own goals. This is self-hacking at its best. To overcome procrastination on a big project, you can use the Zeigarnik Effect: just starting the task creates an “open loop” in your mind that nags you to finish it. To build commitment to a new habit, you can use the IKEA Effect: by investing your own labor in designing your workout or diet plan, you’ll value it more and be more likely to stick with it. To learn a new skill or remember someone’s name, you can use the Spacing Effect, which proves that learning spaced out over time is far more effective than cramming. By understanding the glitches in our own programming, we can write better code for our lives.

Finally, this knowledge comes with a crucial ethical responsibility. There is a fine line between a “nudge” and a “sludge.” A nudge, like the Framing Effect example of setting the default to “opt-out” for organ donation, helps people make better choices that they would likely want to make anyway. It’s using choice architecture for good. A “sludge,” on the other hand, is using these same principles to make it incredibly difficult to cancel a subscription or to trick people into buying something they don’t want. The goal of a true “bias hacker” isn’t to manipulate people against their own interests. It’s to understand the forces that shape our decisions so we can design systems—for our customers, our colleagues, and ourselves—that make it easier to do the right thing. You now have the toolkit. Use it wisely.

0 Comments