- The Great Deception of the Fingertips

- The Traffic Jam of Energy: Understanding Heat Transfer

- The Highway vs. The Dirt Road: Thermal Conductivity

- The Molecular Dance Party

- The Sauna Paradox: When the Tables Turn

- The Biological Thermometer: Why We Are Flawed

- Specific Heat Capacity: The Other Suspect

- Density and Texture: The Minor Players

- Conclusion: The World is Not As It Feels

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis

- Let’s Discuss

- Let’s Play & Learn

The Great Deception of the Fingertips

You wake up on a frigid winter morning. The heating has been off all night, and your house has settled into a uniform, bone-chilling temperature. You roll out of bed, and your bare feet hit the hardwood floor. It’s unpleasant, certainly. It wakes you up. But then, you stumble into the bathroom and step onto the tile, or perhaps you reach out to grab the metal door handle.

The recoil is instant. The metal feels like it is actively biting you. It feels degrees, perhaps decades, colder than the wooden floor you were just standing on. If you were to trust your senses—which we are biologically programmed to do—you would swear in a court of law that the metal handle is freezing, while the wood is merely cool.

But here is the kicker, the scientific punchline that makes a mockery of your intuition: they are exactly the same temperature.

If you took a laser thermometer and pointed it at the wood, the metal, the tile, and the plastic light switch, they would all read the exact same number (assuming they have been sitting in the same room all night). This is the state of thermal equilibrium. Yet, your hand tells you a completely different story. This discrepancy between physical reality and sensory perception is not just a quirk; it is a fundamental lesson in physics and biology. It teaches us that we are terrible thermometers. We are, however, excellent heat-flow detectors.

The Traffic Jam of Energy: Understanding Heat Transfer

To understand why your senses are lying to you, we have to look at what “feeling” temperature actually means. You might think you feel the temperature of an object, but you don’t. You feel the rate at which heat is leaving or entering your body.

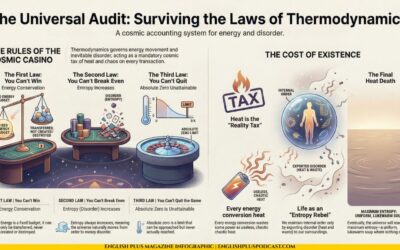

Heat is a social butterfly. It hates being alone and concentrated; it wants to spread out. The Second Law of Thermodynamics essentially tells us that heat will always flow from a hotter object to a colder object until they reach a balance. When you touch the door handle, your hand is roughly 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 Fahrenheit), and the metal is likely around 20 degrees Celsius (68 Fahrenheit).

Because you are the hotter object, heat energy rushes out of your hand and into the metal. Your nerves don’t register “20 degrees Celsius.” They register “Heat is leaving the ship! Abandon ship!” The faster the heat leaves your hand, the “colder” your brain interprets the object to be.

The Highway vs. The Dirt Road: Thermal Conductivity

This brings us to the hero—or the villain—of our story: Thermal Conductivity. This is a measure of how easily heat can move through a material.

Imagine you have a crowd of people (heat energy) trying to leave a stadium. The metal door handle is a massive, twelve-lane superhighway. The moment the crowd steps onto it, they can zoom away at breakneck speeds. The wood, on the other hand, is a bumpy, narrow dirt road full of potholes. The crowd can still leave, but they move slowly. They get stuck.

Metal is a conductor. It has free-moving electrons that act like courier bikes, zipping energy away from the point of contact and distributing it throughout the rest of the metal bar instantly. When you touch the metal, it sucks the heat out of your fingertip and rapidly hands it off to the metal atoms further down the line, making room for more heat to be sucked out of you. It is a highly efficient heat vampire.

Wood is an insulator. Its structure is cellular, filled with air pockets and complex molecules that don’t share energy easily. When you touch the wood, the surface sucks a little bit of heat from your hand, but that heat has nowhere to go. It just sits there, creating a tiny warm buffer zone right under your finger. The wood cannot whisk the energy away, so the rate of heat loss slows down drastically. Your brain feels this slow trickle and thinks, “Eh, not so bad.”

The Molecular Dance Party

Let’s zoom in. If you could shrink yourself down to the size of an atom, the difference between the metal and the wood would look like the difference between a mosh pit and a library.

In the metal, the atoms are arranged in a rigid lattice, but they are swimming in a sea of delocalized electrons. These electrons are the party animals. When heat energy (which is really just vibration) hits them, they go wild. They crash into their neighbors, transferring that kinetic energy with incredible speed. This is why metals are good at conducting both electricity and heat—those free electrons are the universal couriers of the atomic world.

Wood, however, is composed of cellulose, lignin, and air. It’s a complex organic structure. There are no free electrons zipping around. To transfer heat, one molecule has to vibrate and physically nudge its neighbor, who then has to nudge its neighbor. It is a game of “telephone” played by lazy molecules. The message (heat) eventually gets through, but it takes forever.

This explains the sensation. The metal is shouting “Cold!” because it is stripping your thermal energy away at high speed. The wood is whispering “Cold” because it is gently accepting your thermal energy at a leisurely pace.

The Sauna Paradox: When the Tables Turn

Now, you might be thinking, “Okay, so metal is cold and wood is warm.” Not quite. Metal is just an amplifier of reality. It feels colder than it is when it’s cold, but it also feels hotter than it is when it’s hot.

Let’s take a trip to a sauna. The air in there might be 85 or 90 degrees Celsius. The wooden benches are the same temperature. The metal nails holding the benches together are also the same temperature.

You can sit on the wooden bench comfortably. It’s hot, sure, but it doesn’t burn you. But if you accidentally brush your thigh against the metal nailhead? Yikes. You will jump up with a burn mark.

Why? It’s the same mechanism, just in reverse. Now, the object is hotter than you. Heat is trying to flow into your body. The wood, being an insulator, tries to push heat into your skin, but it can only do it slowly. It’s like being hit with a slow stream of water. The metal, however, dumps its heat load into your skin all at once. It conducts that 90-degree energy instantly into your tissues.

This is why chefs use wooden spoons to stir boiling soup. If they used a metal spoon, the heat from the soup would race up the handle and burn their hand. The wooden spoon stays cool at the handle because the heat takes twenty minutes to travel three inches.

The Biological Thermometer: Why We Are Flawed

We have to give a little credit—or blame—to our biology. Our skin is not equipped with a digital readout. We have thermoreceptors, which are specialized nerve endings. Some detect cold, some detect heat.

These receptors are surprisingly adaptive. Have you ever jumped into a swimming pool and felt like you were freezing, but five minutes later the water felt fine? The water didn’t warm up. Your receptors adapted. They stopped firing the “alarm” signal once the rate of heat loss stabilized.

This subjectivity is why we need objective tools like thermometers. A thermometer doesn’t care about rate of flow; it cares about the average kinetic energy of the molecules (which is what temperature actually is).

Specific Heat Capacity: The Other Suspect

While conductivity is the main culprit, we shouldn’t ignore his accomplice: Specific Heat Capacity. This is a measure of how much energy is required to change the temperature of a substance.

Water has a huge specific heat capacity. It takes a lot of energy to heat up water (which is why a watched pot never boils). Metals generally have a lower specific heat capacity. This means they change temperature easily.

When you touch the wood, because it is an insulator, the surface actually warms up slightly to meet your hand’s temperature. You create a local equilibrium. The metal, because it conducts heat away so fast and has a lower capacity to “hold” that local warmth, stays stubbornly at the room temperature, refusing to warm up for you. It remains a cold, unyielding partner in this thermal handshake.

Density and Texture: The Minor Players

There are other factors at play, though they are minor compared to conductivity. Density matters. Metal is denser than wood. There is more “stuff” per square inch in contact with your skin, meaning more avenues for heat to escape.

Texture matters too. Smooth metal makes perfect contact with the ridges of your fingerprints. Rough wood only touches your skin at the high points, leaving tiny gaps of air in between. Air is a fantastic insulator (think of a down jacket or double-glazed windows). Those tiny air gaps between your skin and the wood act as a shield, further slowing down the heat transfer.

Conclusion: The World is Not As It Feels

So, the next time you wince when you touch a cold steering wheel or a metal railing, remember that you are experiencing an illusion. You are not feeling the temperature of the object; you are feeling the exodus of your own energy.

It is a humbling realization. It reminds us that our perception of reality is filtered through the limitations of our biology. We navigate the world based on “feels like,” not “is.” The metal isn’t attacking you; it’s just overly enthusiastic about taking your heat. The wood isn’t protecting you; it’s just too lazy to steal your energy quickly.

In the end, this simple phenomenon—the cold handle versus the warm door—is a window into the atomic structure of the universe. It reveals the invisible dance of electrons and the laws of thermodynamics that govern everything from your morning coffee to the burning of stars. It’s a lot of physics to process before you’ve even brushed your teeth, but that’s the beauty of the world we live in.

Focus on Language

Let’s pause the physics lesson for a moment and look at the words we used to construct it. We didn’t just use scientific jargon; we used a specific blend of descriptive and analytical language to make the invisible visible. Understanding these words doesn’t just help you pass a physics test; it helps you articulate complex sensations and ideas in daily life.

We started with the word counterintuitive. We didn’t explicitly use it in the text above, but the entire concept is counterintuitive. It means something that goes against your gut feeling or common sense. It is counterintuitive that a heavy metal ship can float. It is counterintuitive that the metal and wood are the same temperature. You can use this in business or relationships too: “It seems counterintuitive to raise prices during a recession, but it might save the brand.”

We talked about conductivity. This is a powerhouse word. In our context, it’s about heat. But you can be a conductor of electricity, or even a conductor of information. A person who connects many social groups has high “social conductivity.” If you say, “This meeting has zero conductivity,” you are creatively saying that no ideas are moving; everyone is stuck.

We used the term equilibrium. We spoke of “thermal equilibrium.” This is a state of balance where no change is occurring. In life, we are often searching for work-life equilibrium. Politics is often about finding an equilibrium between freedom and security. It implies a settling down, a stillness after chaos.

We described the metal as an efficient heat vampire. Efficiency is doing the maximum amount of work with the minimum amount of waste. We usually praise efficiency. But here, the metal is too efficient at stealing heat. You can use this to describe people: “He is ruthlessly efficient.” It suggests capability, but perhaps a lack of warmth (pun intended).

We mentioned insulator. An insulator protects and separates. Wood insulates against heat loss. Rubber insulates against electricity. In a social context, money can be an insulator against hardship. Being famous can insulate you from the consequences of your actions. It means to create a buffer.

We used the word discrepancy. We noted the “discrepancy between physical reality and sensory perception.” A discrepancy is a lack of compatibility or similarity between two or more facts. If your bank account says one thing and your receipt says another, there is a discrepancy. It is a polite, formal way of saying “something is wrong here.”

We discussed subjectivity. Our feeling of cold is subjective. Subjective means based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions. Art is subjective. Pain is subjective. The opposite is objective, which means not influenced by personal feelings; factual. The thermometer is objective; your finger is subjective. This is a crucial distinction in any debate.

We used the phrase dissipate. The metal helps heat dissipate. To dissipate is to disperse or scatter. The fog dissipated when the sun came out. His anger dissipated after he ate lunch. It’s a lovely, soft word for fading away or spreading out until gone.

We talked about kinetic energy. Kinetic relates to motion. We live in a kinetic world. You might hear about “kinetic art” (sculptures that move). In military terms, “kinetic action” is a euphemism for active warfare (shooting/moving) as opposed to diplomacy. It implies energy and movement.

Finally, we used the word perceptible. The difference is perceptible. This means able to be seen or noticed. A “barely perceptible nod.” A “perceptible drop in temperature.” It connects the physical world to your senses.

Now, let’s move to the speaking aspect. It is not enough to know these words; you must own them.

Speaking Challenge: The Analogy Architect

I want you to explain a completely different concept—it could be why you are tired, why traffic is bad, or why a relationship failed—using three of the words above: Equilibrium, Insulator, and Dissipate.

Example: “I felt like our relationship lost its equilibrium. We were fighting too much. I tried to use my work as an insulator to protect myself from the stress, but eventually, the love just dissipated.”

Record yourself doing this. Don’t script it perfectly. Just try to weave the words in naturally. This exercise forces your brain to map the definition to a new context, which is the secret to fluency.

Critical Analysis

Now, let’s put on our lab coats and critique our own work. I played the role of the engaging explainer, but did I simplify things too much? Absolutely. In science communication, there is always a trade-off between clarity and absolute precision.

First, we glossed over Surface Roughness. I mentioned texture briefly at the end, but it plays a massive role. Even if you have two metals, a polished chrome bar will feel colder than a rough, sandblasted piece of iron. The contact area is key. By focusing so heavily on atomic conductivity, we might have led you to believe that material type is the only factor, ignoring the macro-structure.

Secondly, we didn’t talk about Moisture Content. Wood isn’t just “wood.” Dry wood is a great insulator. Wet wood? Not so much. Water is a better conductor than air. If the wood floor is damp, it will feel significantly colder than dry wood. We presented “wood” as a monolithic entity, which is scientifically lazy.

Third, we ignored the Body’s Active Response. I mentioned thermoreceptors, but I didn’t mention vasoconstriction. When you touch something cold, your body doesn’t just sit there. It actively constricts blood vessels in your fingers to preserve core body heat. This reduces the heat flow from your core to your skin, making your skin temperature drop faster. The sensation of cold is a mix of the heat loss to the object and your body’s physiological reaction to cut off blood flow. We treated the hand as a passive bag of heat, but it is an active biological machine.

Finally, we used the term “Heat Vampire.” While a fun metaphor, it risks reinforcing a misconception. Vampires suck blood in. Metal doesn’t “suck” cold in; energy flows out. In physics, “cold” does not exist. There is only heat and less heat. We avoided saying “cold flows into your hand” (which is the common wrong idea), but the vampire metaphor walks a fine line.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to spark a fire in the comments (or just in your own brain).

If humans had metal skin, would we perceive temperature differently?

Think about thermal equilibrium. If our skin conducted heat instantly to our core, would we be more sensitive to temperature changes, or would we die of hypothermia instantly? How would “touch” feel?

Is “Cold” real?

Physics says cold is just the absence of heat. But our biology has specific receptors for cold. Does biological reality trump physical reality? If you feel it, is it real?

Why do we design homes with materials that feel uncomfortable?

We love tile and stone floors, yet we hate walking on them in winter. Why do we prioritize aesthetics (how it looks) over haptics (how it feels)? Is this a failure of architecture?

Could we invent a material that feels warm like wood but is strong like steel?

This is a materials science question. Can we decouple conductivity from strength? (Hint: Composites and Aerogels). What would that change for construction or clothing?

How much of our “reality” is just a sensory illusion?

If we can’t trust our sense of hot and cold, what about color? (Colors are just wavelengths). What about solidity? (Atoms are mostly empty space). Where do you draw the line between illusion and useful perception?

0 Comments