The heat in Buenos Aires on Christmas Eve was a physical weight. It pressed against the windows of the Casa de los Abuelos, turning the nursing home into a greenhouse of stale air and the scent of floor wax.

Valeria sat in her wheelchair by the window, watching the heat shimmer off the pavement outside. Her hands, gnarled like the roots of an old ombú tree, rested on her lap. Once, these hands had been elegant, draped over the shoulders of the finest leads in San Telmo. Once, her feet, now swollen in orthopedic slippers, had moved with the precision of a switchblade, carving shapes into the wooden floors of the milongas.

Now, she was eighty-two. She was a number on a chart. She was “Grandma” to nurses who didn’t know she had never had children, who didn’t know she had birthed only art.

The common room was decorated with limp tinsel and a plastic tree that listed to the left. The television was blaring a commercial for Pan Dulce.

Valeria closed her eyes. Silence, she prayed. Just a moment of silence.

“Do you need water, Doña Valeria?”

It was Lucas, the night orderly. He was young, barely twenty, with messy hair and a uniform that was always untucked. He was mopping the linoleum floor, moving the bucket with a rhythmic slosh-clack, slosh-clack.

“I need a new pair of legs,” Valeria snapped, though without heat. “But water will do.”

Lucas smiled. He liked her sharpness. It was better than the vacancy he saw in the other residents. He poured her a glass of water.

As he turned back to his mop, he began to hum.

It wasn’t a conscious sound. It was a low, vibrating melody, barely audible over the television. But Valeria heard it. Her head snapped up.

He wasn’t humming “Jingle Bells.” He wasn’t humming a pop song.

He was humming the opening bars of El día que me quieras—”The Day You Love Me.” Carlos Gardel. The anthem of longing.

Valeria stared at him. “Stop.”

Lucas froze, the mop hovering. “I’m sorry. Is it annoying?”

“Where did you learn that?” she demanded. “That is not music for boys who wear sneakers.”

Lucas shrugged, looking a little embarrassed. “My grandfather. He plays the bandoneón. He plays it every Christmas Eve.”

Valeria looked at the boy. Really looked at him. She saw the way he held his posture, even while mopping.

“The bandoneón breathes,” Valeria whispered, her eyes unfocusing, seeing a room from fifty years ago, thick with cigarette smoke and perfume. “It sighs like a lover.”

“Yes,” Lucas said softly. “That’s what he says.”

He looked at the radio on the counter. He walked over and turned the volume of the pop music down. He took his phone out of his pocket, tapped the screen, and set it on the table.

The opening notes of the tango swelled into the room. The strings, the piano, and then the heavy, weeping gasp of the bandoneón.

The air in the room changed. The smell of floor wax faded, replaced by the phantom scent of rose water and sweat.

Lucas walked back to her. He didn’t pick up the mop. He wiped his hands on his trousers. He stood tall, his chest lifting, his chin tilting down. He extended a hand.

“Mademoiselle?” he said, his voice dropping an octave, imitating the old codes of the dance hall.

Valeria looked at his hand. Then she looked at her legs, useless and heavy under the blanket.

“Don’t mock me, boy,” she said, her voice trembling. “I cannot stand.”

“You don’t need to stand to dance tango,” Lucas said. “Tango is not in the feet. It is in the chest.”

He stepped closer. He didn’t try to pull her up. Instead, he took her right hand in his left. He placed his right hand gently on her shoulder. He leaned in, creating the abrazo—the embrace—closing the space between them until their foreheads almost touched.

He began to move.

He didn’t move her chair. He moved around her. He pivoted, his feet sliding across the linoleum in slow, deliberate ochos. He guided her upper body, swaying her gently left, then right, in perfect sync with the sobbing rhythm of the music.

Valeria closed her eyes. She felt the tension in his frame, the lead and the follow. She pressed her hand against his palm, offering resistance, creating the tension that made the dance alive.

For three minutes, she wasn’t crippled. She was floating. She felt the ghost of the pivot, the snap of the head turn. She felt the passion of the music traveling from his hand to hers, bypassing her broken body completely.

Lucas spun, dipping her slightly in the chair, his eyes locked on hers with the intensity of a partner, not a nurse. He treated her not as fragile glass, but as a woman who knew the steps.

When the song ended, he held the final pose, his breath steady, his eyes shining.

He slowly released her hand. He stepped back and bowed, a sharp, respectful inclination of the head.

Valeria opened her eyes. Her heart was racing, a feeling she hadn’t felt in a decade. A tear leaked from the corner of her eye, tracing a path through the powder on her cheek.

“You lead well,” she whispered. “For a boy in sneakers.”

Lucas grinned, the spell breaking, returning to being a twenty-year-old orderly. “Merry Christmas, Valeria.”

He picked up his mop.

Valeria turned her face to the window. The heat was still there, the city was still loud, and she was still old. But inside her chest, the music was still playing. She tapped her finger on the armrest, one-two-three-four, and waited for the night to come.

A Prayer for the Fire That Remains

Let us speak now to the rhythm that outlives the body. Let us speak to the feet that are still, but which remember every step of the dance.

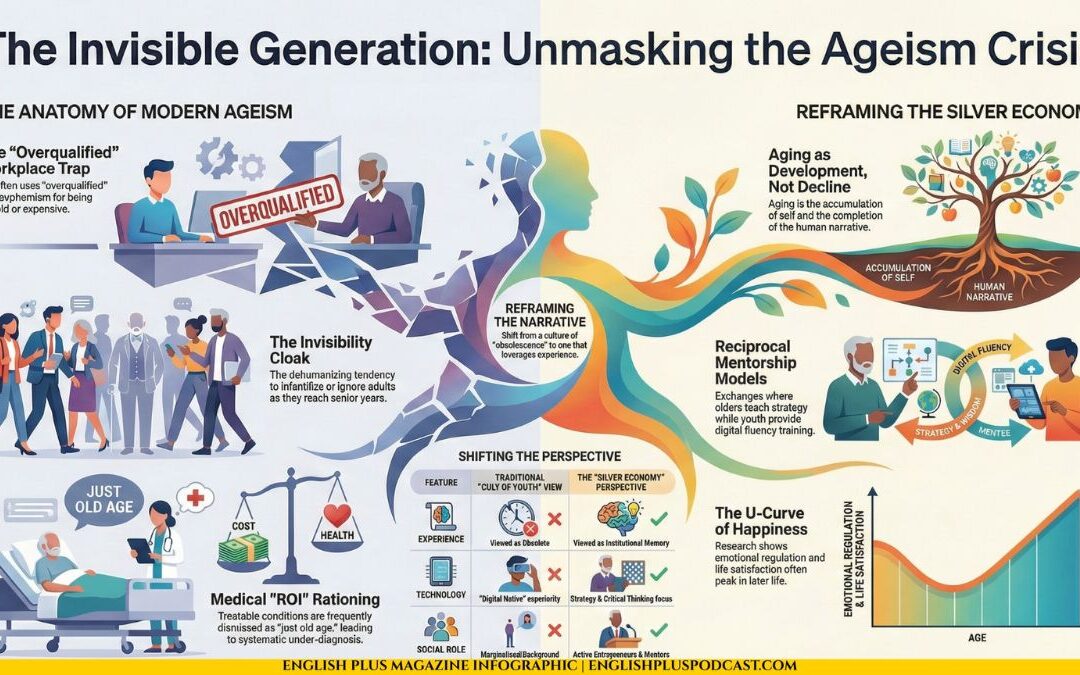

To the hands that are weathered like old roots, yet still crave the touch of another. To the hearts that beat inside chests grown frail, beating not just for survival, but for passion, for art, for the memory of a night when the air was thick with perfume and possibility. We are a world that worships the new, the strong, the straight spine. We look at the wheelchair and see an ending. We look at the wrinkled skin and assume the fire has gone out.

Let us confess the cruel truth to one another: We dismiss the elderly as history books on a shelf. We dust them, we preserve them, we keep them safe, but we do not open them. We forget that they were once the leads in the drama of life. We forget that the woman staring out the window was once the queen of the floor, that the man in the corner once broke hearts with a glance. We rob them of their present by refusing to honor their past.

Let us ask for the vision to see the dancer inside the patient. To look past the swollen joints and the slow drift of age, and see the sharp, terrifying precision of the soul. To realize that desire does not age, that the need to be held, to be led, to be spun, does not wither just because the muscles have failed.

May we have the grace to offer the hand. Not the hand of the nurse checking a pulse, but the hand of the partner offering an embrace. The hand that says: I know who you are. I know what you can do.

Let us learn the lesson of the midnight tango: The music does not stop just because the orchestra has gone home. It plays in the memory. It plays in the blood. And sometimes, all it takes is one person willing to listen, one person willing to set aside the mop and take up the frame, to turn a sterile room into a ballroom.

So, let us change the station. Let us play the song that hurts. Let us bow to the masters who are sitting in our midst, disguised as the frail. Let us glide across the linoleum as if it were the finest wood, honoring the dignity of a spirit that refuses to sit still.

May we find that when we hold the past in our arms, we are not holding a burden; we are holding a flame.

The body may forget. The heart remembers the step. Let us dance.

0 Comments