Have you ever stuck with a decision—even when it was clearly not working out—just because you’d already invested time, money, or effort into it? If so, you’ve experienced the sunk cost fallacy, a common psychological bias that keeps people committed to choices based on past investments rather than future benefits. Let’s explore what the sunk cost fallacy is, why it happens, and how you can recognize and overcome it in your own life.

What Is the Sunk Cost Fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency to continue a behavior or endeavor because of previously invested resources—time, money, or effort—even when continuing is no longer the best option. The term “sunk cost” refers to resources that have already been spent and cannot be recovered. Logically, these costs should not influence future decisions, but emotionally, they often do.

For example, imagine you’ve bought an expensive ticket to a concert, but on the day of the event, you feel sick. Even though you won’t enjoy the concert, you might feel compelled to go because you’ve already spent the money. This is the sunk cost fallacy in action.

Why Does the Sunk Cost Fallacy Happen?

Several psychological factors contribute to the sunk cost fallacy:

1. Loss Aversion

Humans are wired to dislike losses more than we enjoy gains. The idea of “wasting” resources we’ve already invested feels painful, so we try to justify those investments by sticking with the decision.

2. Commitment and Consistency

Once we’ve committed to something, we want to appear consistent. Changing course can feel like admitting we were wrong, which many of us find uncomfortable.

3. Emotional Attachment

When we invest in something, we often develop an emotional connection to it. This attachment can cloud our judgment and make it harder to walk away.

4. Fear of Regret

We worry that abandoning a decision will lead to regret. Ironically, continuing with a bad choice often creates even more regret down the line.

Common Examples of the Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy appears in many areas of life, often without us realizing it. Here are a few common examples:

- Relationships: Staying in an unhappy relationship because of the years you’ve spent together.

- Careers: Sticking with a job you dislike because you’ve invested time and effort climbing the corporate ladder.

- Hobbies and Projects: Continuing a project you no longer enjoy because you’ve already spent money on materials or equipment.

- Entertainment: Finishing a boring movie or book simply because you’ve already started it.

- Financial Investments: Holding onto a failing investment because selling would mean realizing a loss.

How to Overcome the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Breaking free from the sunk cost fallacy requires a shift in mindset. Here are some strategies to help you make more rational decisions:

1. Focus on Future Outcomes

Instead of dwelling on past investments, ask yourself: “What will benefit me most going forward?” Future gains, not past costs, should drive your decisions.

2. Reframe “Wasted” Costs

Recognize that sunk costs are a part of life and don’t define you. Treat them as learning experiences rather than failures.

3. Seek Objective Perspectives

Consult with someone who isn’t emotionally invested in the situation. A fresh perspective can help you see the bigger picture.

4. Practice Decision-Making Awareness

When faced with a tough decision, pause and ask: “Am I continuing this because it’s the best choice, or because I’ve already invested in it?”

5. Embrace Change

Remember that changing direction isn’t a failure—it’s a sign of growth and adaptability.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy in Everyday Life

Once you start recognizing the sunk cost fallacy, you’ll see it everywhere. Have you ever finished a meal you didn’t enjoy just because you paid for it? Or kept wearing uncomfortable shoes because they were expensive? These small examples show how deeply ingrained this bias can be.

Understanding the sunk cost fallacy can help you make better decisions, not just in major life choices but in everyday situations. It’s a tool for freeing yourself from unproductive commitments and focusing on what truly matters.

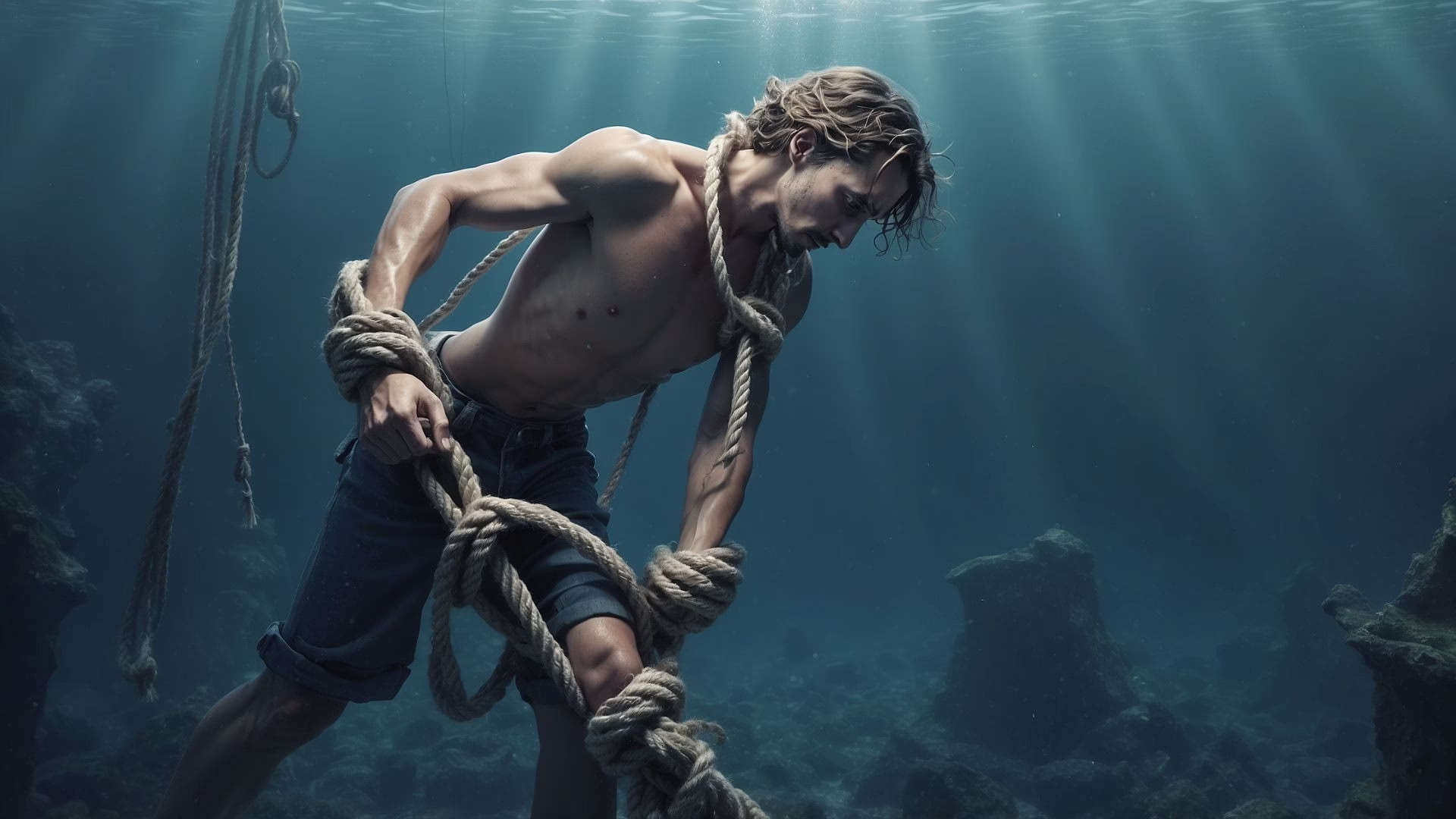

The sunk cost fallacy is a powerful psychological trap that keeps us tethered to bad decisions, but it’s not unbreakable. By shifting your focus from past investments to future possibilities, you can make choices that serve your best interests. Recognizing the sunk cost fallacy in your life is the first step toward breaking free from its grip and living with greater clarity and purpose.

So, the next time you’re tempted to stick with something just because you’ve already invested in it, ask yourself: “Is this decision about the past—or the future?”

Let’s Talk

The sunk cost fallacy—it’s something we’ve all fallen into at some point, haven’t we? It’s so sneaky, too, because it doesn’t announce itself as a bias. Instead, it wraps itself up in feelings of responsibility, persistence, and loyalty. Have you ever caught yourself thinking, “I can’t stop now; I’ve already spent so much time on this”? It could be a hobby that’s no longer fun, a job you’ve outgrown, or even watching a terrible movie you refuse to turn off because, well, you’re halfway through. That’s the sunk cost fallacy, quietly steering your decisions.

But here’s the tricky part: it feels logical in the moment. The idea of “wasting” something—whether it’s money, time, or effort—is emotionally uncomfortable. It’s like we’re trying to protect the value of what we’ve already spent. But think about it: that investment is already gone. It’s like trying to drink from an empty cup—there’s nothing left to salvage.

Here’s an example I’ve seen often: holding onto a subscription or service you don’t use anymore. You think, “I’ve already paid for this; I should get my money’s worth.” But if it’s not adding value to your life anymore, isn’t keeping it around just doubling the loss? This happens in relationships too. How many times have we heard someone say, “I can’t leave—we’ve been together for years”? But time alone doesn’t make something worth continuing.

And then there’s the career angle. Maybe you’ve spent years in a job that doesn’t excite you anymore, but you think, “I’ve come so far; I can’t throw it all away.” But is staying worth sacrificing your future happiness and growth? Shifting gears doesn’t erase what you’ve accomplished—it builds on it.

The sunk cost fallacy doesn’t just play on our emotions; it can also trick us into believing we’re being rational. We think, “If I just stick it out a little longer, it might turn around.” But how often does that actually happen? And more importantly, is the potential upside worth the energy you’re continuing to pour into it?

Maybe the real question is: how do we reframe the way we see those past investments? What if we looked at them not as losses but as experiences? After all, isn’t it better to learn and pivot than to stay stuck because of an imaginary scoreboard? And here’s something else to think about: do you believe that letting go of something is always a loss, or can it sometimes be the most freeing choice you make?

Let’s Learn Vocabulary in Context

Let’s start with “sunk cost.” This term refers to any investment of time, money, or effort that can’t be recovered. Think about that gym membership you paid for but never use—those fees are a sunk cost. It’s a practical term, but it pops up in casual conversations too, like when someone says, “I don’t want to waste my sunk costs on this.”

Next, there’s “fallacy.” A fallacy is a mistaken belief or error in reasoning. The sunk cost fallacy is just one example, but you might use this word in broader contexts, like “It’s a fallacy to think working harder always leads to success.”

Let’s talk about “bias.” A bias is a tendency to think or act in a certain way, often subconsciously. The sunk cost fallacy is a type of cognitive bias that affects decision-making. In daily life, you might say, “I’m trying to overcome my bias against trying new foods.”

Then there’s “investment.” This word typically refers to putting resources—like money or time—into something with the hope of a return. But investments don’t always pay off, and understanding that can help you make smarter decisions.

Consider “attachment.” This is the emotional connection we form with things, people, or ideas. Attachment is one reason the sunk cost fallacy is so powerful—it’s hard to let go of what we’re emotionally invested in.

How about “commitment”? Commitment means dedicating yourself to something, and it’s usually a good thing. But in the context of the sunk cost fallacy, overcommitment can lead to poor choices.

Let’s look at “rational.” Being rational means making decisions based on logic rather than emotions. Avoiding the sunk cost fallacy often requires taking a rational approach.

Next is “value.” Value refers to the worth or importance of something. One way to avoid the sunk cost fallacy is to focus on the future value of your choices rather than the past.

Another useful word is “regret.” Regret is the feeling of wishing you’d made a different choice. The fear of regret often keeps people stuck in the sunk cost fallacy, but recognizing that regret is part of life can help you move forward.

Finally, there’s “growth.” Growth is about learning and improving, even when it means changing direction. Letting go of a sunk cost is often a step toward personal growth.

Here’s something to think about: which of these terms resonates with you the most? And have you ever experienced a moment where recognizing a sunk cost helped you make a better decision?

Let’s Discuss & Write

Discussion Questions

- Can you think of a time when the sunk cost fallacy influenced one of your decisions? How did it impact the outcome?

- Why do you think humans have such a hard time letting go of past investments?

- How can recognizing the sunk cost fallacy help us make better choices in relationships or careers?

- Are there situations where sticking with a decision despite sunk costs might still be the right call?

- How does reframing sunk costs as learning experiences rather than losses change the way we view them?

Writing Prompt

Write about a moment in your life when you realized you were caught in the sunk cost fallacy. Describe the situation, what made you recognize the bias, and how you ultimately decided to move forward. Reflect on what you learned from the experience and how it changed your approach to decision-making. Aim for 250–300 words, focusing on emotions and lessons learned.

0 Comments