- The Myth of the 50/50 Split

- Emotional Labor: The Invisible Glue

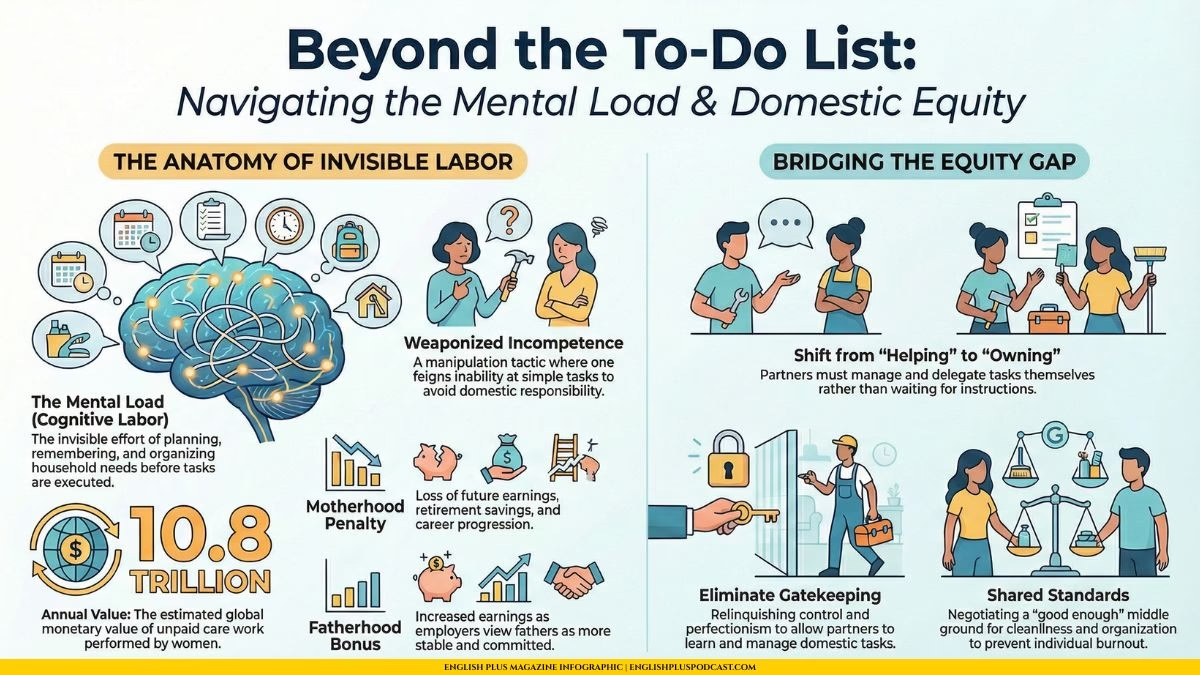

- Weaponized Incompetence: A Strategic Defense

- Social Equity: The “Boys Will Be Boys” Trap

- The Economic Impact of Unpaid Care Work

- Closing the Door on Inequality

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis: Playing Devil’s Advocate

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Modernist

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

We spend an inordinate amount of time dissecting the glass ceiling. We count the number of female CEOs in the Fortune 500, we analyze the gender pay gap down to the cent, and we write endless think pieces about “leaning in” or “girlbossing” our way to the top. And don’t get me wrong, that stuff matters. It matters a lot. But while we are busy storming the boardroom, there is a much quieter, much more persistent inequality happening right in our living rooms, kitchens, and the recesses of our exhausted brains.

It is the inequality of the “Second Shift.” It is the reason why, statistically speaking, women are more likely to be burnt out by 8:00 PM than their male counterparts, even if they both worked the exact same number of hours at the office. We need to stop pretending that gender equality ends when we clock out. In fact, for many people, that is exactly where the real work begins.

We are going to take a hard, honest, and occasionally uncomfortable look at domestic and social equity. We are going to talk about who remembers to buy the toilet paper, who manages the family social calendar, and why “helping out” is the most dangerous phrase in the English language.

The Myth of the 50/50 Split

If you ask most modern couples, they will tell you they aim for equality. They will say, “We split everything down the middle.” And they probably believe it. He does the dishes; she cooks. He takes out the trash; she does the laundry. It feels fair. But if you scratch the surface of that arrangement, you often find a glaring disparity in the type of work being done.

There is a distinction between execution and management. In the corporate world, managers—the ones who plan, delegate, and oversee—are paid more than the people who simply execute the tasks. Yet in the domestic sphere, the management role is almost exclusively unpaid, invisible, and defaulted to women.

The Weight of the “Mental Load”

This brings us to the concept of the “Mental Load,” or cognitive labor. Doing the laundry is execution. It involves physical labor: putting clothes in the machine, pressing a button, folding them. That is the easy part.

The Mental Load is noticing that the laundry basket is full. It is knowing which clothes can go in the dryer and which ones need to be hung up so they don’t shrink. It is realizing that your kid has soccer practice tomorrow and needs their uniform clean tonight. It is monitoring the supply of detergent and adding it to the grocery list before it runs out.

When one partner has to ask, “What can I do to help?” they have already failed the equity test. By asking for instructions, they are positioning themselves as the subordinate and their partner as the manager. The manager now has to expend mental energy to delegate the task, explain how to do it, and follow up to make sure it was done. Often, it feels easier to just do it yourself. This creates a cycle where one person carries the entire cognitive map of the household while the other person gets to live in a house that magically stocks itself with toothpaste.

Emotional Labor: The Invisible Glue

If cognitive labor is the brain of the household, emotional labor is the heart—and it is just as exhausting. Emotional labor is the act of managing feelings and relationships to keep everything running smoothly. It is the invisible glue that holds families and social circles together, and it is rarely recognized as “work.”

The Social Secretary and the Peacekeeper

Who remembers his mother’s birthday? Who buys the card, signs it from “us,” and mails it? Who notices when a friend is having a bad week and sends a check-in text? Who soothes the toddler’s tantrum in the middle of the supermarket while the other parent looks at their phone?

This is emotional labor. It involves a constant, low-level scanning of the emotional environment. It is anticipating needs before they become problems. In many relationships, women are the designated “worriers.” They worry about the kids’ social development, the aging parents’ health, and whether the dinner guests are having a good time.

This isn’t because women are biologically better at caring; it is because they are socially conditioned from childhood to prioritize the comfort of others. Men, conversely, are often conditioned to prioritize their own autonomy. When we treat emotional labor as a hobby rather than a job, we devalue the person doing it. We call it “nagging” when a woman reminds her partner to call his dad, rather than recognizing it as her managing his social capital for him.

Weaponized Incompetence: A Strategic Defense

Now, we have to talk about something that might make a few people squirm. It is a phenomenon called “Weaponized Incompetence.” This is when a person feigns inability to do a simple task so poorly that their partner eventually takes over and never asks them to do it again.

We’ve all seen the sitcom trope: the bumbling husband who tries to change a diaper and ends up duct-taping it to the baby’s leg, or who tries to go grocery shopping and comes back with three bags of chips and no milk. The audience laughs, the wife rolls her eyes and says, “Move over, I’ll do it,” and the status quo is preserved.

But in real life, this isn’t funny; it’s a manipulation tactic. It is a way of opting out of domestic responsibility by leveraging the low expectations society places on men. If a man says, “I’m just not good at cleaning the bathroom,” he is essentially saying, “My time is too valuable to learn how to scrub a toilet, so I will let you do it.”

The Standard of “Good Enough”

This ties into the standards we accept. Often, the partner doing the domestic labor has a higher standard of cleanliness or organization. The other partner might argue, “You’re just too picky. The house looks fine.”

This is a convenient argument. It frames the person who wants a clean house as neurotic or controlling, rather than framing the person who tolerates filth as lazy. But equity requires a shared standard. It requires negotiation. If one person is comfortable living in squalor and the other needs order to function, simply defaulting to the lower standard isn’t fair—it forces the organized person to live in constant stress or do all the work. True equity means meeting in the middle, where both partners take ownership of the shared space.

Social Equity: The “Boys Will Be Boys” Trap

Gender inequality doesn’t stay inside the house; it spills out into the street. Social equity is about how we navigate public spaces and how we are perceived by the world. It is about the subtle, daily calculations that women have to make that men often don’t even realize exist.

The Safety Tax

Consider the simple act of walking home at night. For a man, the calculation might be: “Is it raining? Is it a long walk?” For a woman, the calculation is a complex risk assessment: “Is that street light out? Are there people around? Are my headphones too loud? Are my keys in my hand? Is that guy following me?”

This is the “Safety Tax.” It is the mental energy consumed by the constant threat of violence or harassment. It limits where women go, when they go there, and how they act. It is a restriction on freedom that has nothing to do with laws and everything to do with culture.

And it starts young. We tell girls to “be careful,” “cover up,” and “don’t walk alone.” We tell boys to “be bold” and “take risks.” We excuse aggressive behavior in boys with the phrase “boys will be boys,” implying that their biology makes them uncontrollable. This absolves them of responsibility while placing the burden of safety entirely on girls. Until we teach boys that they are responsible for their actions and teach girls that they have a right to occupy space without fear, social equity will remain a fantasy.

The Economic Impact of Unpaid Care Work

Let’s pivot to the hard numbers, because money talks. If we were to put a price tag on all the unpaid cooking, cleaning, and caregiving done primarily by women around the world, it would amount to trillions of dollars. In fact, Oxfam estimates that the monetary value of unpaid care work globally for women aged 15 and over is at least $10.8 trillion annually. That is three times the size of the world’s tech industry.

This labor is the backbone of the economy. It produces the workforce (by raising children) and sustains the workforce (by feeding and caring for adults). Yet, because no money changes hands, economists essentially pretend it doesn’t exist. It doesn’t count toward GDP.

The Motherhood Penalty vs. The Fatherhood Bonus

This invisibility has real-world consequences for women’s bank accounts. When women take time out of the workforce to care for children or aging parents, they don’t just lose their current salary; they lose future earning potential, retirement savings, and career progression. This is the “Motherhood Penalty.”

Conversely, men often experience a “Fatherhood Bonus.” Studies have shown that after having children, men’s earnings often increase, as employers view them as more stable and committed providers. Women, meanwhile, are viewed as distracted or less committed. This double standard perpetuates the wage gap far more effectively than any overt discrimination.

Closing the Door on Inequality

So, how do we fix this? It isn’t easy. You can pass a law to mandate equal pay, but you can’t pass a law to make your partner remember to buy milk. Domestic and social equity requires a cultural shift. It requires uncomfortable conversations at the dinner table.

It requires men to step up—not just to “help,” but to own. To take on the mental load. To worry about the birthday cards. To scrub the toilet without being asked. To call out their friends for sexist behavior.

And it requires women to let go. To stop gatekeeping domestic tasks because “he won’t do it right.” To tolerate the learning curve. To demand more than just a paycheck partner.

True equality isn’t just about who sits in the corner office. It’s about who sits at the kitchen table planning the grocery list. It’s about creating a world where care is valued as much as commerce, and where partnership truly means sharing the load—every single ounce of it.

Focus on Language

Let’s dive into the language we used in this article. We are dealing with sociology and psychology here, so the vocabulary is specific, nuanced, and incredibly useful for describing the dynamics of modern life. I want to highlight ten key phrases, break them down, and show you how to use them to sound more articulate and precise.

First up is “Cognitive Labor.” We used this interchangeably with “Mental Load.” Cognitive relates to the process of thinking. Cognitive labor is the invisible work of planning, remembering, and organizing. In real life, you might use this at work too. If your boss expects you to organize all the office parties on top of your actual job, you could say, “I am happy to help, but this is adding a lot of cognitive labor to my plate that isn’t in my job description.” It sounds much more professional than saying “I’m stressed out thinking about this.”

Next, let’s look at “Weaponized Incompetence.” This is a powerful phrase. It describes pretending to be bad at something so someone else does it. You can use this with friends or roommates. If your roommate leaves the dishes because they claim they “don’t know how to load the dishwasher correctly,” you can jokingly (or seriously) accuse them of weaponized incompetence. It calls out the behavior for what it is: a strategy, not a lack of skill.

Then we have “Social Conditioning.” This refers to the process of training individuals in a society to act or respond in a manner generally approved by the society in general and peer groups within society. We mentioned that women are conditioned to be caregivers. You can use this to explain why you feel pressure to act a certain way. “I feel like I have to say yes to everyone because of my social conditioning, but I’m trying to set better boundaries.”

Let’s talk about the “Second Shift.” This is a classic sociological term coined by Arlie Hochschild. It refers to the workload of people (usually women) who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. If you work all day and come home to cook and clean, you are working the second shift.

We used the term “Gatekeeping.” In the conclusion, we said women need to stop gatekeeping domestic tasks. Gatekeeping is the activity of controlling, and usually limiting, general access to something. In a domestic context, it means criticizing how your partner does a task so much that they stop doing it, effectively keeping control of that task for yourself. “I realized I was gatekeeping the laundry because I didn’t like how he folded the towels.”

Another great phrase is “Invisible Labor.” This is work that goes unnoticed and unacknowledged but is essential. Emotional labor is a form of invisible labor. You can use this to appreciate someone. “Thank you for planning the itinerary; I know that’s a lot of invisible labor that made the trip run smoothly.”

We mentioned the “Glass Ceiling.” This is the unacknowledged barrier to advancement in a profession, especially affecting women and members of minorities. While the article focused on the home, this term is essential for gender discussions. “She broke the glass ceiling by becoming the first female Vice President.”

Let’s look at “Default Parent.” This is the parent the school calls when a kid is sick, the one the kids ask for juice, the one who knows the schedule. Even if both parents are present, one is usually the default. “I love my husband, but I’m definitely the default parent; the school doesn’t even have his number on file.”

We used the word “Disparity.” This means a great difference. We talked about the disparity in the type of work being done. It’s a formal, academic word for “inequality” or “gap.” “There is a huge economic disparity between the two neighborhoods.”

Finally, “Autonomy.” We said men are conditioned to prioritize their autonomy. Autonomy is the right or condition of self-government; freedom from external control. In relationships, balancing togetherness and autonomy is key. “I value my autonomy, so I need some time alone on weekends.”

Speaking Section: The “I Statement” Challenge

Now, let’s put this into practice. When discussing domestic equity, things can get heated. The most important speaking skill here is the “I Statement.” Instead of accusing (“You never do the dishes”), you describe your experience (“I feel overwhelmed when I come home to a sink full of dishes”).

I want you to try a challenge. Think of a task—at home or at work—where you feel you are carrying the Mental Load. I want you to articulate it using the vocabulary we just learned.

Structure:

“I feel like I am carrying the cognitive labor for [Task] because [Reason]. It creates a disparity in our free time. Can we discuss how to share this invisible labor?”

Example:

“I feel like I am carrying the cognitive labor for the grocery shopping because I’m the only one tracking what we run out of. It creates a disparity because I have to spend my Saturday morning planning. Can we discuss how to share this invisible labor?”

Try saying this out loud. Notice how using the specific vocabulary makes the problem sound objective and solvable, rather than just an emotional complaint. It elevates the conversation.

Critical Analysis: Playing Devil’s Advocate

We have painted a fairly condemning picture of the current state of domestic affairs. We’ve labeled men as weaponized incompetents and women as overburdened martyrs. But is it really that simple? To be rigorous thinkers, we must challenge our own premises. Let’s play devil’s advocate and look at the “traditional” division of labor through a different lens: Efficiency and Choice.

First, let’s look at the Specialization of Labor. This is an economic theory championed by Nobel laureate Gary Becker. He argued that a household is most efficient when partners specialize. If one person focuses entirely on the market (earning money) and the other focuses entirely on the home (domestic labor), the “firm” (the family) maximizes its total output.

From this perspective, the 50/50 split is actually inefficient. It requires both people to be mediocre at everything, switching contexts constantly, rather than mastering one domain. Is it possible that the “Second Shift” feels so heavy not because of inequality, but because modern couples are trying to do everything instead of specializing? Maybe the problem isn’t that men aren’t doing enough laundry; maybe the problem is that we have devalued the role of the homemaker so much that we force everyone into the workforce, leaving no one to manage the home efficiently.

Second, we must address Biology and Hormones. We touched on social conditioning, but evolutionary psychologists would argue that we cannot ignore biology completely. Women, generally speaking, have higher levels of oxytocin and estrogen, hormones linked to bonding and nurturing. Men generally have higher testosterone, linked to risk-taking and competition.

Could it be that the “Emotional Labor” gap isn’t just oppression, but a reflection of biological predisposition? If women are naturally more attuned to social cues and emotional needs due to evolutionary selection pressures (raising vulnerable infants), is it “unfair” that they do more of it? Or is it simply them playing to a biological strength? Ignoring biology completely in favor of a purely social constructionist view might be blinding us to why these patterns are so incredibly persistent across cultures and history.

Third, let’s talk about Choice Feminism. If a woman chooses to take on the mental load—if she genuinely enjoys planning the parties and managing the house—is it still oppression? There is a danger in the modern discourse of pathologizing women’s choices. By labeling all domestic work as “burden” or “unpaid drudgery,” are we insulting the women who find fulfillment in it? Are we suggesting that the only “real” work is corporate work?

Perhaps the ultimate goal shouldn’t be a mathematical 50/50 split of chores, but a 50/50 split of valued leisure time. If one partner earns $500k a year and works 80 hours a week, and the other partner manages the home, is it “inequity” if the earner doesn’t scrub the toilet? Or is that a fair division of labor based on contribution?

Finally, we must critique the concept of the “Mental Load” discourse itself. Does it infantilize men? By constantly repeating that men are incapable of seeing a dirty sock or remembering a birthday, do we create a self-fulfilling prophecy? Maybe the “Gatekeeping” we mentioned is a bigger factor than we admit. If women constantly correct men’s domestic attempts, men eventually withdraw. Is the “Mental Load” sometimes a self-imposed burden of perfectionism?

These are uncomfortable questions. They don’t have easy answers. But if we want to talk about true equity, we have to look at the messy reality of economics, biology, and individual choice, not just the idealized version of equality.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to spark a debate. There are no right answers, only different perspectives.

Is “Weaponized Incompetence” real, or are we just bad at teaching?

Think about a time you tried to learn a new skill. Did you fail on purpose? Or were you just bad at it? Is it fair to attribute malice to a partner’s clumsiness? How do we distinguish between laziness and a genuine lack of aptitude?

Should the government pay stay-at-home parents a salary?

We know unpaid care work is worth trillions. If we value it, should we pay for it? Would this liberate women by giving them financial independence, or would it trap them in the home by incentivizing them to leave the workforce?

If you earn significantly more than your partner, should you do fewer chores?

Does money buy you out of domestic labor? If you pay for the house, the cleaner, and the vacations, is it fair to expect your partner to manage the household? Or does “partnership” mean equal chores regardless of income?

Are we raising our sons differently than our daughters regarding chores?

Look at the kids in your life. Do we ask girls to “help mommy” in the kitchen while boys are asked to “help daddy” with the heavy lifting? Or are boys just allowed to go play? How does this shape the “Default Parent” of the future?

Is the “Mental Load” actually a control issue?

If you are stressed because the towels are folded “wrong,” is that your partner’s fault, or yours? Can we reduce the mental load by simply caring less about perfection? Is “good enough” actually good enough?

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Modernist

Danny: Welcome back. We’ve been talking about the “Second Shift,” the “Mental Load,” and the exhausting reality of trying to have it all while doing it all. It’s a modern conversation, but the roots go back centuries. To help us untangle this mess, I wanted to talk to a woman who didn’t just write about gender inequality; she dissected it with a scalpel. She famously said that a woman needs money and a room of her own to be free. She is the author of Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, and the slayer of the “Angel in the House.” Please welcome the incomparable Virginia Woolf. Virginia, thank you for joining us in the 21st century.

Virginia: Thank you, Danny. It is… louder here than I expected. And brighter. Do you really need all these lights? It feels like an interrogation room, though I suppose for a woman, the world has always been a bit of an interrogation room. “Who are you? Who do you belong to? Why aren’t you smiling?”

Danny: I’ll try to keep the interrogation friendly. I brought you here because I feel like you predicted everything we’re struggling with today. We have a term now called the “Mental Load”—the invisible work of managing a household. The planning, the worrying, the anticipating. Does that sound familiar to you?

Virginia: It sounds like the very air I breathed. You call it the “Mental Load.” I called it the “cotton wool” of daily life. It is the stuff that wraps around you, soft and suffocating, preventing you from seeing the sharp edges of reality. It is the dinner that must be ordered. The stockings that must be mended. The mood of the husband that must be managed. It is a thousand tiny threads that bind Gulliver to the ground. You cannot write a symphony if you are wondering if the butcher sent the right cut of lamb. The mind cannot be in two places at once, and for women, the mind has always been leased to the domestic.

Danny: “Leased to the domestic.” That’s a perfect way to put it. We talked about how even when women work full-time jobs, they come home and start a second job.

Virginia: Ah, yes. The professional woman. I wrote about her. I wondered what would happen when women finally entered the professions. I see now that you have entered them, but you have not left the drawing room. You are straddling two horses, and I imagine it is quite uncomfortable. You see, Danny, in my time, the enemy was clear. We called her “The Angel in the House.”

Danny: The Angel in the House. Can you explain her? Because I think she’s still haunting us.

Virginia: She is immortal, I fear. She was the phantom who lived in every house. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught, she sat in it—in short, she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. And above all—she was pure.

Danny: That sounds… exhausting.

Virginia: It is death. It is the death of the self. When I tried to write, she would slip behind me and whisper, “My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anyone guess that you have a mind of your own.”

Danny: So what did you do?

Virginia: I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defense. Had I not killed her, she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. But, Danny, hearing you speak of this “Mental Load,” I fear I may have only stunned her. She seems to have woken up in your century, put on a blazer, and bought a smartphone.

Danny: She definitely has a smartphone. And now she whispers, “Did you sign the permission slip? Did you freeze the breast milk? Did you answer that email at 11 PM?”

Virginia: Precisely. The Angel has modernized. She no longer demands you sit in the draught; she demands you “have it all.” Which is, of course, a trap. To have it all is to do it all. And to do it all is to have no time to be.

Danny: You famously said a woman needs 500 pounds a year and a room of her own. In today’s money, that’s financial independence and personal space. We talked about the economic impact of unpaid labor—trillions of dollars. Do you think money is the key to solving this?

Virginia: Money is the key to everything, Danny. I was considered quite vulgar for saying so. People prefer to talk about “rights” and “suffrage” and “justice.” Those are noble words. But intellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women, then, have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry. That is why I have laid so much stress on money and a room of one’s own.

Danny: Because if you have money, you can buy your way out of the drudgery?

Virginia: Exactly. If you have 500 pounds a year, you can hire a cook. You can hire a cleaner. You can buy solitude. Solitude is expensive, Danny. Silence is a luxury good. In a poor house, there are no walls between you and the noise of the family. The stew pot is always boiling in the same room where you are trying to think. If women are to be equal, they must first be wealthy enough to purchase their own time back from the world.

Danny: But isn’t that just passing the oppression down? If I hire a cleaner, I’m just paying another woman to do the drudgery so I can go be a CEO. It doesn’t solve the issue that the work itself is devalued.

Virginia: A sharp point. You are passing the bucket to a woman with less than 500 pounds a year. It is an imperfect solution. But until men—and society—value the scrubbing of the floor as much as they value the writing of the brief, someone must scrub. And as long as it is the woman of the house who scrubs, she will never write the brief. Or if she does, it will be a tired, distracted brief.

Danny: Let’s talk about men. In the article, we discussed “Weaponized Incompetence.” The idea that men pretend to be bad at domestic tasks so they don’t have to do them.

Virginia: Oh, I know this well. The “great men” of history. The Carlyles, the Miltons. They were geniuses, you see. They could comprehend the movements of the stars, or the history of the Roman Empire, but the operation of a teapot? The location of their own socks? Impossible! It was beneath their great minds.

Danny: Do you think it was a conscious strategy?

Virginia: I think it is the privilege of the conqueror. The conqueror does not need to know how the tent is erected; he only needs to know how to command the army. For centuries, men have been the conquerors in the drawing room. They have been trained to believe that their time is “gold” and women’s time is “lead.” If a man burns the toast, it is a charming eccentricity. If a woman burns the toast, it is a failure of her primary function. Why would a man learn to make toast properly if his incompetence buys him an hour of leisure? He is acting quite rationally. Selfishly, but rationally.

Danny: You had a very unique marriage with Leonard Woolf. He was incredibly supportive. He printed your books. He cared for you when you were ill. Was he the exception?

Virginia: Leonard was… a miracle. But he was also a man who understood the value of work. We ran the Hogarth Press together. We were partners in ink. But even then, Danny, the domestic shadows lurked. The servants had to be managed. The meals had to be planned. Even with a Leonard, the weight of the “house” sits differently on a woman’s shoulders. A man enters a house to rest; a woman enters a house to work. Even if she sits in a chair, her eyes are scanning for dust. It is an ocular affliction.

Danny: “An ocular affliction.” I love that. It’s like the Safety Tax we talked about—the constant scanning for danger outside, and the constant scanning for dirt inside.

Virginia: Yes. We are always scanning. We are the sentinels of the trivial. And the trivial is the enemy of the sublime. You cannot write Hamlet if you are worried about the dust on the mantelpiece.

Danny: I want to ask about “Emotional Labor.” The birthday cards, the soothing of egos. You wrote a lot about how women serve as “looking-glasses” for men.

Virginia: Ah, yes. Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size. That is our prime function in society. To make men feel big.

Danny: That’s a devastating quote.

Virginia: It is the truth. Why do you think men are so angry when women criticize them? Or when women stop doing this emotional labor? Because if the woman stops serving as the mirror, the man shrinks. He sees himself as he truly is—perhaps a bit small, perhaps a bit incompetent at finding his socks. It is terrifying for him. He needs the mirror. He needs the Angel to tell him, “You are strong, you are brilliant, the house runs by magic because you are the king.”

Danny: So when we ask men to do 50% of the emotional labor, we aren’t just asking them to do work; we’re asking them to smash the mirror?

Virginia: We are asking them to be ordinary. And no one who has been treated as a king wants to be ordinary. To remember your own mother’s birthday is not heroic; it is mundane. To soothe your own child’s tantrum is not a special occasion; it is Tuesday. You are asking men to descend from the pedestal of the “Provider” into the mud of the “Carer.” It is a demotion, in their eyes.

Danny: That explains why there’s so much resistance. It’s an identity crisis.

Virginia: Precisely. And it is an identity crisis for women too. Because if we are not the Angels—if we are not the benevolent managers of everyone’s happiness—then who are we? We have been told for centuries that our value lies in our utility to others. If I am not useful, am I still lovable? That is the question every woman asks herself at 3 AM.

Danny: You talk about this with such clarity, but you lived a hundred years ago. It’s depressing that we haven’t solved it. We have the vote. We have the jobs. We have the credit cards. What are we missing?

Virginia: You are missing indifference.

Danny: Indifference?

Virginia: Yes. You care too much. You care about being the perfect mother. You care about being the perfect employee. You care about the opinion of the other mothers at the school gate. You have taken the Angel in the House and merged her with the Captain of Industry. You are trying to be both. You need to learn to be indifferent. To let the dust settle. To let the toast burn. To let the man shrink.

Danny: That sounds impossible. The guilt would eat us alive.

Virginia: The guilt is the Angel speaking! “My dear, the children will suffer! My dear, the house is a mess!” You must strangle her. It is a violent act, Danny. To create a self, you must destroy the servant. You must be willing to be called “selfish.” “Selfishness” is the most important virtue a woman can possess. Because without a self, you have nothing to give but a reflection.

Danny: “Selfishness is a virtue.” That’s going to be a hard sell for the mommy bloggers.

Virginia: Let them blog. I will be in my room, writing, with the door locked.

Danny: Let’s pivot to the public sphere. We talked about “Social Equity” and the “Safety Tax.” You famously were denied entry to a library at a university because you were a woman. You had to be accompanied by a man.

Virginia: Yes. The beadle shooed me away like a stray cat. It was a physical reminder that the world of the mind was a gated community. You talk about “safety” on the streets—fear of violence. But there is also the safety of belonging. To walk into a room and feel you have a right to be there. Women still walk into boardrooms, or parliaments, or even public debates, and feel they are trespassing. We lower our voices. We apologize for speaking. We say, “I think,” instead of “I know.” We are still waiting for the beadle to throw us out.

Danny: How do we stop apologizing?

Virginia: By taking up space. By buying the alcohol and the tobacco and the room of one’s own. By writing sentences that are too long and too opinionated. By refusing to be charming. Charm is the chain. Break it.

Danny: You know, there’s a debate today about “Choice Feminism.” The idea that if a woman chooses to be a housewife, that’s a feminist choice because she made it. What would you say to the woman who says, “But I like being the Angel in the House”?

Virginia: I would say… beware. I would say that a choice made in a cage is not the same as a choice made in a meadow. If you have been told from birth that your glory is in the kitchen, and you choose the kitchen, is that a free choice? Perhaps. But I would ask: Do you have the money? Do you have the room? If your husband left you tomorrow, would you be destitute? If the answer is yes, then you are not a housewife; you are a dependent. And dependence is never a state of freedom.

Danny: That’s the “Rentier Capitalism” of relationships. You don’t own your life; you’re renting it from your husband.

Virginia: A brutal way to put it, but yes. And the rent is your smile. The rent is your silence. The rent is your constant, exhausting sympathy.

Danny: I want to ask you about the future. If you could look at 2026, are you hopeful?

Virginia: I am… intrigued. You have inventions that I could not have dreamed of. Machines that wash the dishes! Machines that wash the clothes! By all logic, women should have hours and hours of free time.

Danny: You’d think so. But we just filled that time with more work.

Virginia: Because you did not change the mind; you only changed the machinery. You used the extra time to raise the standard of cleanliness, or to parent the children more intensely. This is the tragedy of the “Mental Load.” It expands to fill the time available. You need to stop optimizing the housework and start abolishing it.

Danny: Abolishing it? How?

Virginia: By deciding it does not matter. By deciding that a book is more important than a clean floor. By deciding that a conversation is more important than a perfect dinner. We are obsessed with the material maintenance of life. We should be obsessed with life itself.

Danny: You make it sound so radical. To just… not do it.

Virginia: It is the only revolution that matters. The strike. The domestic strike. If every woman in the world sat down tomorrow and refused to soothe a temper or find a sock, the world would end in twenty minutes. Men would have to build a new world. And perhaps, in that new world, they would learn where the socks are kept.

Danny: I love that image. The Apocalypse of the Unfound Sock.

Virginia: It would be chaotic, but it would be the beginning of civilization.

Danny: Before we go, I have to ask. You wrote Orlando, a book about a character who changes from a man to a woman and lives for centuries. You were playing with gender fluidity way before it was cool. What do you think about our modern conversations on gender?

Virginia: I think it is marvelous. I always felt that the mind is androgynous. It is man-womanly or woman-manly. The purely masculine mind is too hard; the purely feminine mind is too soft. We must be both. To see you deconstructing these boxes—”man,” “woman,” “provider,” “carer”—it gives me hope. Perhaps if we stop being “men” and “women” and start being “people,” the laundry will finally get done by whoever is standing closest to the machine.

Danny: That is the dream. A gender-neutral laundry utopia.

Virginia: We can hope, Danny. We can hope.

Danny: Virginia Woolf, you have been absolutely illuminating. Thank you for dissecting our modern mess with your modernist mind.

Virginia: Thank you. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go find a room with a lock on the door. This studio has far too many people in it.

Danny: Fair enough. And for our audience, remember: Kill the Angel. Buy the room. And for the love of literature, let the toast burn.

Virginia: And let him buy his own milk!

Danny: You heard her.

0 Comments