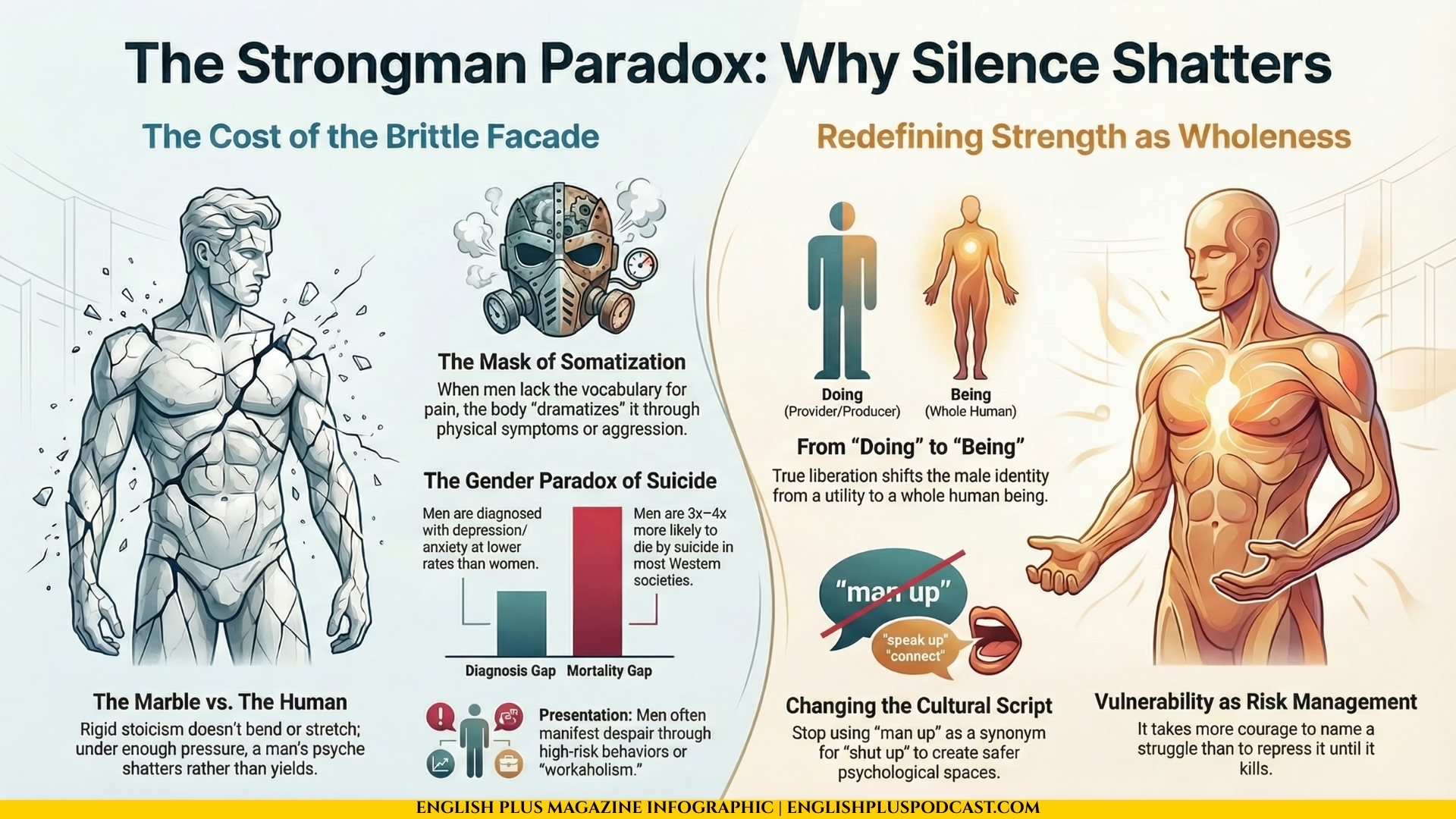

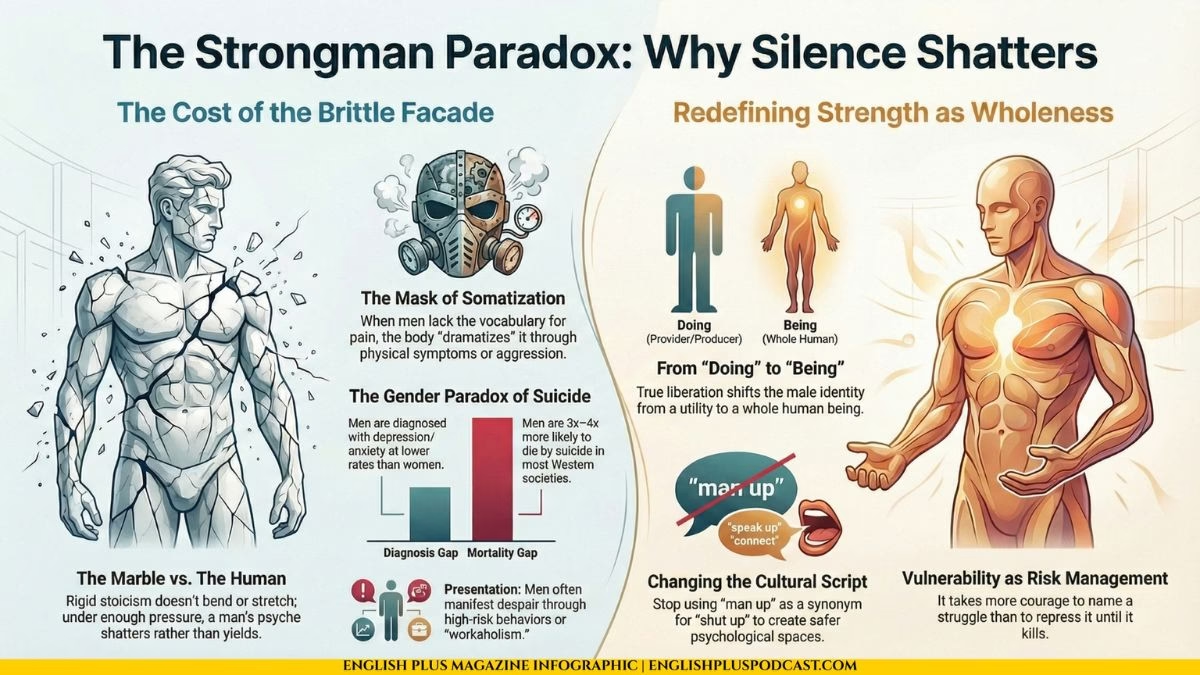

There is a specific kind of silence that fills a room when a man enters it, carrying the weight of the world but refusing to acknowledge that his shoulders are tired. We have all seen it. We have all felt it. It is the silence of the father who stares out the window while the dinner gets cold, the brother who laughs too loud at a joke that isn’t funny, or the friend who disappears for weeks only to return as if nothing happened. We call this strength. We look at the marble statue of the stoic man—unflinching, unfeeling, unbreaking—and we applaud his resilience. But if you look closely at marble, you realize something terrifying: it doesn’t bend. It doesn’t stretch. When enough pressure is applied to marble, it doesn’t yield; it shatters.

This is the Strongman Paradox. We have socially engineered a definition of masculinity so rigid that it has become brittle, a psychological architecture where silence is equated with stability. But what happens when the silence becomes a scream that no one can hear? We need to dissect this cultural script, not to attack men, but to understand why the very armor designed to protect them is often the thing that suffocates them.

The Cultural Scripts of Stoicism

The Archetype of the Stone Face

We inherit our scripts early. Before a boy can even tie his own shoes, he is often taught how to tie up his emotions. It starts on the playground. A scraped knee results in tears, and the immediate, almost reflex response from the world is, “Big boys don’t cry.” It seems innocent enough, a way to encourage resilience. But language is a virus. That phrase mutates over time. It transforms from “don’t cry over a scraped knee” to “don’t show pain when your heart is broken,” “don’t show fear when you are lost,” and “don’t ask for help when you are drowning.”

This is the architecture of modern stoicism. Unlike the philosophical Stoicism of Marcus Aurelius—which was about emotional regulation and logic—modern performative stoicism is about emotional suppression. It is the belief that vulnerability is a defect in the manufacturing process of a man. We see this reinforced in every piece of media we consume. The hero is the one who endures torture without speaking, the one who solves the crime while bleeding out, the one who saves the world but cannot save his own marriage because he can’t say “I’m sad.” We treat men as utilities, valued for what they can provide, protect, or produce. When a utility malfunctions, we fix it or replace it; we don’t ask it how it feels. Consequently, men learn to hide their “malfunctions” to avoid obsolescence.

The Cost of the Stiff Upper Lip

This repression creates a bifurcation in the male psyche. There is the public self, the Strongman who has the answers, and the private self, often strictly guarded, where the anxiety lives. The energy required to maintain the wall between these two selves is exhausting. It is a metabolic tax on the soul. When you spend your life holding up a shield, you eventually forget how to put it down, even when you are safe in your own home.

The tragedy is that this silence is often misinterpreted by loved ones as indifference. A partner might think, “He doesn’t care,” when in reality, he cares so much that he is paralyzed by the fear of showing weakness. He doesn’t have the vocabulary for his own interiority because he was never given the dictionary. We expect men to write poetry about their feelings when they were only taught the alphabet of grunt and nod.

The Statistical Nightmare

The Gender Paradox in Suicide

If we move from the philosophical to the empirical, the picture gets darker. When we look at mental health statistics, we encounter a jarring discrepancy often called the “gender paradox of suicide.” Generally speaking, women are diagnosed with depression and anxiety at significantly higher rates than men. They are also more likely to attempt suicide. However, men are between three to four times more likely to die by suicide than women across most Western societies.

Why is this? Why is the diagnosis rate lower but the mortality rate higher? It comes down to the lethality of intent and the reluctance to seek intervention. Men, conditioned to be decisive and effective, often apply these same traits to the act of self-destruction. They choose more violent, irreversible methods. But the more insidious factor is the diagnosis gap. The lower rate of depression diagnosis in men doesn’t necessarily mean men are less depressed; it means they are less likely to walk into a doctor’s office and say, “I am hurting.”

The Mask of Somatization

Instead of verbalizing pain, the male body often dramatizes it. This is called somatization. A man might not say he is anxious, but he will complain of chronic back pain, digestive issues, or insomnia. He will treat the symptom because treating the symptom is masculine—it’s fixing a mechanical problem. Treating the root cause—the emotion—feels like a surrender.

Furthermore, men often “treat” their depression through external behaviors rather than internal reflection. We see higher rates of substance abuse, high-risk behaviors, and aggression. A man driving his car at 120 miles per hour down a highway at 2 AM might not look depressed to the casual observer; he looks reckless. But that recklessness is often a desperate attempt to feel something other than numbness, or to silence the noise in his head with the roar of an engine. We are mislabeling male despair as male bad behavior.

The Mid-Life Crisis: A Misdiagnosis?

The Red Sports Car Fallacy

We have all cracked jokes about the mid-life crisis. The balding man who suddenly buys a leather jacket, gets a divorce, and buys a Porsche. We treat it as a punchline, a pathetic attempt to recapture youth. But if we peel back the layers of this cliché, we often find untreated clinical depression.

Mid-life is a precarious time. The scripts of youth—”work hard, get the girl, buy the house, be the provider”—have been played out. The man reaches the top of the mountain he was told to climb, only to find the air is thin and he is incredibly lonely. He realizes that the identity he built was purely performative. He spent forty years being a Human Doing rather than a Human Being.

Dismantling the Facade

The erratic behavior associated with the mid-life crisis is often a frantic attempt to escape the crushing weight of this realization. It is not necessarily about wanting to be young; it is about wanting to be alive. When a man hasn’t developed the emotional tools to process regret, aging, or shifting identity, he defaults to the only tools he knows: action and acquisition. He buys the car because he can’t buy peace of mind. He changes his partner because he can’t change himself.

If we stopped mocking the mid-life crisis and started treating it as a legitimate psychological breaking point, a manifestation of accumulated silent trauma, we might save families. We might save lives. It is not a joke; it is a symptom of a soul that has been starving for authenticity for decades.

Redefining Strength

Vulnerability as the New Armor

The conversation is shifting, albeit slowly. We are beginning to see a new definition of masculinity emerge, one that does not view emotionality as the antithesis of strength. We are starting to understand that true courage is not the absence of fear, but the willingness to face it, name it, and share it.

Vulnerability is not weakness; it is the ultimate risk management. It takes more guts to look a friend in the eye and say, “I am struggling,” than it does to repress that struggle until it kills you. This isn’t about men becoming “soft.” It’s about men becoming whole. A soldier who can admit he is traumatized is not a worse soldier; he is a man beginning the process of healing so he can continue to function. A father who cries in front of his son is not teaching the boy to be weak; he is teaching the boy that he is human.

Changing the Narrative

To change the statistics, we have to change the stories. We need to stop congratulating men for suffering in silence. We need to stop using phrases like “man up” as a synonym for “shut up.” We need to create spaces where men can speak without the fear of judgment, where the brotherhood is built on shared reality rather than shared bravado.

The “Strongman” is a myth, and it is a dangerous one. It is a statue that cannot move, cannot breathe, and cannot love. It is time to smash the marble. Beneath the rubble, we might just find flesh and blood—messy, complicated, scared, and wonderfully real. And that, paradoxically, is where the real strength lies.

Focus on Language

Let’s dive right into the language we used because words are the tools we use to build our reality and if we don’t understand the tools we can’t build anything sturdy. I want to look at the word Paradox. We used this right in the title. A paradox is a situation or statement that seems to contradict itself but might actually be true. We talked about the “Strongman Paradox”—the idea that acting strong actually makes men fragile. You can use this in real life all the time. You might say, “It’s a paradox that I have to drink coffee to sleep because it calms my ADHD,” or “The paradox of technology is that it connects us to people far away but distances us from people in the same room.” It’s a great word to use when life gets messy and illogical.

Then we talked about Stoicism. Now, I mentioned this isn’t just about the Greek philosophy; in modern context, it usually refers to the endurance of pain or hardship without the display of feelings and without complaint. When you say someone is stoic, you’re saying they are like a rock. But remember how we used it? We talked about performative stoicism. That means faking it. You can use this when you see someone clearly hurting but refusing to admit it. “He’s maintaining this air of stoicism, but I know he’s terrified.” It helps you describe that specific kind of emotional wall.

Speaking of walls, let’s look at the word Facade. It literally means the face of a building, usually the deceptive front that looks nicer than the rest of the structure. In a social context, it’s a deceptive outward appearance. We talked about dismantling the facade. We all have one. You might have a “professional facade” at work where you act like you know exactly what you’re doing even when you’re panicked. You can say, “I kept up the facade of being happy until I got home and collapsed.” It’s a powerful word because implies that there is something real hiding behind the fake front.

We also used the word Visceral. This comes from “viscera,” which means your internal organs, your guts. So when something is visceral, it is felt in the gut. It’s deep, instinctual, and emotional rather than intellectual. When I said the silence becomes a scream, that is a visceral image. You use this when a feeling is physical. “I had a visceral reaction to that horror movie,” or “His hatred for injustice is visceral.” It’s not just in his head; it’s in his body.

Let’s touch on Bifurcation. That’s a fancy word that simply means splitting into two branches or parts. I used it to describe the split in the male psyche—the public self and the private self. You can use this whenever things split. “There was a bifurcation in the road,” or “The bifurcation of the political party caused chaos.” It’s a very precise word that makes you sound incredibly sharp when you use it to describe a complex split in opinion or identity.

Then there is Somatization. This is a psychological term where mental struggles show up as physical symptoms. This is crucial for understanding why we get sick when we are stressed. You can use this when your friend says they have a headache before a big exam. “That might be somatization; your anxiety is turning into pain.” It helps us link the mind and the body.

We talked about the Archetype. An archetype is a very typical example of a certain person or thing, like a recurring motif in literature or life. The “Strongman” is an archetype. The “Damsel in Distress” is an archetype. We use this to describe roles people fall into. “He is fitting into the rebel archetype perfectly.” It helps you analyze behavior not just as individual choices, but as patterns we learn from stories.

I also used the word precarious. I used it to describe mid-life. Precarious means not securely held or in position; dangerously likely to fall or collapse. If you are standing on a wobbly ladder, your position is precarious. If you are living paycheck to paycheck, your financial situation is precarious. It adds a sense of danger and instability to your description.

Let’s look at Interiority. This refers to inner character or nature, or the quality of being inward. When I said men don’t have the vocabulary for their interiority, I meant they can’t describe their inner world. You can use this to talk about depth. “That novel has a lot of interiority; we really hear the character’s thoughts.” It’s a great word for discussing art, psychology, or deep relationships.

Finally, let’s talk about Catharsis. I didn’t use this explicitly in the text, but the whole article is driving toward it. Catharsis is the process of releasing, and thereby providing relief from, strong or repressed emotions. Breaking the marble statue is a form of catharsis. Crying is catharsis. You can use this when you finally let something out. “Writing that angry email was such a catharsis, even though I didn’t send it.”

Now, for the speaking section. I want to challenge you to use the concept of the Facade. We all wear masks. In your speaking practice, I want you to describe a time when you had to maintain a facade. Maybe you were the leader of a team and things were going wrong, but you had to look confident. Maybe you were a parent terrified for your child but you had to look calm. Describe that moment. Use the word visceral to describe how you felt inside, and stoic to describe how you looked outside. Record yourself telling this story for two minutes. Listen to it. Did you sound authentic? This is how we practice not just English, but emotional intelligence in English.

Critical Analysis

Now, I want to pivot. We have spent a lot of time deconstructing the “Strongman” and looking at the dangers of silence. And while everything we discussed is backed by sociology and psychology, it is my job—and your job as a critical thinker—to stop and ask: “Wait a minute. Is it really that simple?” Let’s play the devil’s advocate. Let’s poke some holes in the argument, not to destroy it, but to see if it holds water from every angle.

One major perspective we might have missed is the evolutionary argument. We talked about stoicism as a “cultural script,” implying it is entirely learned and therefore can be entirely unlearned. But is that entirely true? Evolutionary psychology might suggest that there is a biological imperative for risk-taking and emotional suppression in males. Throughout human history, the hunters and protectors couldn’t afford to be paralyzed by fear or overcome with weeping while a predator was attacking the tribe. In those moments, stoicism wasn’t toxic; it was a survival mechanism. By labeling all male silence as “dysfunctional,” are we pathologizing a trait that actually kept the human species alive for thousands of years? We need to be careful not to swing the pendulum so far that we classify natural, testosterone-driven competitive or protective instincts as purely negative.

Furthermore, we need to critique the “talk therapy” solution. The article implies that the solution to male depression is for men to open up and talk like women do. But does that actually work for everyone? There is research suggesting that men often process emotion through action rather than conversation. This is sometimes called “instrumental grieving.” A man might mourn a lost friend by building a bench in his honor, not by sitting in a circle and crying about it. If we force men into a therapeutic model designed primarily around verbal processing, we might be setting them up for failure. Perhaps the issue isn’t that men don’t process emotion, but that we don’t value the way they process it. Maybe fixing the car is the therapy. By dismissing these activities as “distractions” or “facades,” we might be invalidating a legitimate form of male healing.

We also have to look at the concept of “Toxic Masculinity.” While the article avoided using that buzzword explicitly, it danced around the concept. We need to be critical of how this term is applied. It can become a catch-all bin where we throw anything about men that makes society uncomfortable. If a man is assertive, is he toxic? If he is competitive, is he toxic? If he wants to be a provider and takes pride in that, is he reinforcing a damaging script? There is a danger that in trying to liberate men from the “Strongman” box, we are just shoving them into a new box called the “Sensitive Man,” which is just as restrictive if it doesn’t align with who they naturally are. True liberation shouldn’t be about forcing men to cry; it should be about giving them the option to cry without losing their status.

And finally, let’s look at the “diagnosis gap.” We assumed that men are depressed but undiagnosed. But could it be that the diagnostic criteria for depression are biased toward female presentation? The standard symptoms often include weeping, sadness, and withdrawal. If men manifest depression through anger, risk-taking, and workaholism, perhaps the medical community isn’t just “missing” them; perhaps the medical community is using the wrong ruler to measure the problem. We need to question the very definitions of mental health we are using.

So, while the “Strongman Paradox” is a real and dangerous phenomenon, the solution isn’t just “men need to talk more.” It’s likely far more complex, involving biology, alternative coping mechanisms, and a medical system that needs to update its definitions. Critical thinking demands we look at the gray areas, not just the black and white.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to get you thinking and talking. When you discuss these in the comments or with friends, try to move past the easy answers.

1. Is stoicism ever necessary?

Don’t just say “no.” Think about professions like surgeons, pilots, or firefighters. If your surgeon starts crying about the tragedy of life in the middle of your heart surgery, is that good? Discuss the difference between functional compartmentalization and emotional repression. Where is the line?

2. How do partners and spouses reinforce the “Strongman” script?

We often blame “society” or “other men,” but what happens in relationships? Have you ever seen a woman tell a man to “man up”? Or a partner who says they want vulnerability but then pulls away when the man actually cries? Discuss the subtle ways intimate partners police masculinity.

3. Is the “Mid-Life Crisis” a luxury?

We talked about the mid-life crisis as an emotional breaking point. But does everyone get one? Or is this something only people with a certain amount of money and time can afford to have? Does a man working three jobs to survive have time to question his identity? How does class intersect with this psychological crisis?

4. Can video games and sports be genuine therapy for men?

Challenge the idea that “talking” is the only cure. Can the camaraderie of a sports team or an online gaming squad provide a safe space for emotional regulation that looks different from traditional support groups? Or are these just escapism?

5. If you could redesign the “Man” of the future, what would he look like?

Try to build a new archetype. If the “Strongman” is out, what is in? Is it the “Soft Man”? The “Balanced Man”? What traits would he keep from the past, and what traits would he adopt from the present? Be specific.

Fantastic Guest: An Interview with Ernest Hemingway

Danny: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to a very special segment of the show. We’ve spent some time dissecting the “Strongman Paradox”—the idea that the pressure to be unshakeable, silent, and stoic is actually what shatters us. We’ve looked at the sociology, the psychology, and the statistics. But theory only gets you so far. Sometimes, to understand the weight of a mask, you have to talk to the man who sculpted the face.

My guest today is a giant of literature, a Nobel Prize winner, an ambulance driver, a hunter, a fisherman, and perhaps the undisputed architect of 20th-century masculinity. He taught generations of men that courage is “grace under pressure” and that the best way to handle emotion is to leave it out of the sentence entirely. Please welcome the ghost, the myth, the legend… Ernest Hemingway. Papa, welcome to the show.

Hemingway: You talk too much. The introduction was longer than some of my short stories. And you didn’t offer me a drink.

Danny: I’m sorry, Ernest. It’s a dry studio. Insurance policies, you know? Plus, it’s 10:00 AM.

Hemingway: The time of day is a construct for people who have jobs they hate. And a dry studio is a construct for people who are afraid of the truth. But fine. I’ll take coffee. Black. As bitter as a critique from Gertrude Stein.

Danny: I can do that. So, Ernest—can I call you Ernest? Or do you prefer Papa?

Hemingway: Call me Papa if you want me to pay the bill. Call me Ernest if you want to fight. Since there’s no bill and you look like you’ve never thrown a punch in your life, stick to Hemingway.

Danny: Fair enough. Hemingway it is. Look, I brought you here because we’re talking about the “Strongman.” And in many ways, you are the blueprint. The boxing, the bullfighting, the wars, the hunting safaris. You created this archetype of the man who acts rather than feels. Looking back at it now, from the… other side… was it exhausting?

Hemingway: Exhausting? No. Carrying a wounded Italian soldier on your back while your leg is full of Austrian shrapnel is exhausting. Writing is exhausting. Being a man? Being a man was just the job. You don’t complain about the job. That’s the first rule.

Danny: But that’s exactly what I want to dig into. “You don’t complain.” You famously coined the “Iceberg Theory” regarding your writing—the idea that you leave seven-eighths of the story underwater, unwritten, just implied. It made for brilliant fiction. But it seems like you applied that to your emotional life, too. You kept seven-eighths of the pain underwater.

Hemingway: If you show everything, it’s cheap. It’s melodrama. You write about the action. You write “Nick sat against the wall.” You don’t write “Nick was sad and terrified and missed his mother.” The reader feels it more if you don’t say it.

Danny: In fiction, yes. I agree. You changed literature forever. But in life? We’re seeing that when men leave seven-eighths of their emotions underwater, they drown. We discussed the suicide rates, the depression… the silence. You lived that silence.

Hemingway: I didn’t live silence. I lived loud. I laughed loud, I fought loud.

Danny: But did you hurt loud? Or did you hurt quietly while cleaning a shotgun?

Hemingway: You have a sharp tongue for a man sitting in a padded chair. Listen. You think we didn’t know we were hurting? You think because we didn’t have therapists and podcasts and “mental health days” that we were stupid? We knew. But the world was different. The world was trying to kill us, most of the time. I saw two world wars. I saw the Spanish Civil War. When the sky is falling, you don’t sit around discussing your inner child. You hold up the roof.

Danny: I get that. Survival requires suppression. We talked about that—the evolutionary argument. But the war ended, Hemingway. The sky stopped falling. But you—and the men who idolized you—kept holding up the roof even when the house was empty. Why couldn’t you put it down?

Hemingway: Because once your muscles set that way, they don’t unset. You become the thing you practice. We practiced hardness. We practiced it until we turned into stone. And you’re right about the brittle part. I read your article. You said marble doesn’t bend, it shatters. I shattered. I know that better than anyone. Ketchum, Idaho. 1961. That wasn’t a victory lap. That was the statue crumbling.

Danny: It’s profound to hear you say that. Really. Because so many men look at your end and they censor it. They remember the bulls of Pamplona, but they forget the electroshock therapy at the Mayo Clinic. They forget the paranoia. Do you think that paranoia—that feeling that the Feds were watching you, that you were losing your mind—was the result of decades of not speaking?

Hemingway: It wasn’t paranoia if they were actually watching me, Danny. The FBI had a file on me thick enough to stop a bullet. But… the darkness. The “Black Dog,” as Churchill called it. Yes. It feeds on silence. It’s a fungus. It grows in the dark. If you expose it to sunlight—to talk, to vulnerability—maybe it shrinks. But I didn’t know how to do that. I knew how to write a sentence that was true. “The river was cold.” That is true. “I am scared.” That felt… false. It felt like a betrayal of the character I had created.

Danny: “The character I had created.” That’s the key, isn’t it? You weren’t just Ernest. You were Hemingway. You were a brand before brands existed. Did you feel trapped by the beard and the sweater and the shotgun?

Hemingway: Everyone is a character, Danny. You’re a character right now. “The Insightful Host.” You’re performing. The difference is, my audience was the whole world. And they wanted Papa. They wanted the guy who could drink a quart of whiskey and shoot a lion. If I had come out and said, “Actually, I’d really like to just sit in a garden and weep about how much I miss my first wife, Hadley,” they wouldn’t have bought the books.

Danny: So it was a commercial transaction? You sold them masculinity, and they bought it?

Hemingway: I sold them certainty. That’s what men want. That’s what the “Strongman” is. It’s not about muscles. It’s about certainty. The Strongman knows what to do. The Strongman doesn’t doubt. Modern men—your generation—you are plagued by doubt. You doubt your jobs, your relationships, your gender roles, your diet. It’s paralyzing. I offered a world where a man knew exactly what he was: He was the one who fished the marlin. End of story. It was seductive. Even to me.

Danny: It is seductive. I feel it. I think every man feels that pull to just simplify, to shut up and build something. But we talked about the “Mid-Life Crisis” in the article. You had… what? Four wives?

Hemingway: Four. Magnificent women. All of them. Better than I deserved.

Danny: Was the jumping from marriage to marriage a form of that crisis? A way to reset the story because the emotional plot got too complicated?

Hemingway: You’re acting like a psychiatrist now. It’s annoying. But… maybe. When a marriage gets deep, really deep, you have to show yourself. You have to be naked, and I don’t mean physically. I mean you have to show the rot. You have to show the fear. And when that started happening, when the woman started seeing the terrified boy inside the Great Hemingway… I’d leave. I’d find a new one who only knew the legend. It’s easier to be a legend to a stranger than a human to a wife.

Danny: “It’s easier to be a legend to a stranger than a human to a wife.” That might be the most heartbreaking thing I’ve ever heard. That’s the Strongman Paradox in one sentence. You trade intimacy for admiration.

Hemingway: Admiration is a drug, Danny. Intimacy is work. And I was lazy about the things that mattered, and diligent about the things that didn’t. I spent hours perfecting a paragraph about a fish, and minutes working on my marriage.

Danny: Let’s talk about the “Bifurcation” we mentioned. The public vs. the private self. You were known for this sparse, masculine, journalistic prose. But I’ve read your letters. Especially the ones to people you really trusted. They’re different. They’re softer. They’re playful. You used nicknames. You were… tender.

Hemingway: A man can be tender with a cat. Or a good friend. Or a lover, in the dark. But you don’t put that in the newspaper. You don’t put that on the dust jacket.

Danny: But why not? Why is tenderness the enemy of the Strongman?

Hemingway: Because tenderness looks like an opening. In boxing, if you drop your guard to hug your opponent, you get knocked out. We were raised to believe life is a fight. Always. If life is a fight, tenderness is a tactical error.

Danny: And do you still believe life is a fight? Now that you’ve been… out of the ring for a while?

Hemingway: I think life is a fight, yes. But I think I was fighting the wrong opponent. I was fighting the critics. I was fighting the other writers—trying to beat Faulkner, trying to beat Tolstoy. I was fighting my own reputation. I should have been fighting the despair. And you don’t fight despair with fists. You fight it with… connection. Which is something I was terrible at. I had entourages, not connections.

Danny: That connects to what we discussed about “Instrumental Grieving” or “Action as Therapy.” You were a man of action. When you were sad, you went fishing. When you were angry, you boxed. Do you think that worked for you? Or was it just distraction?

Hemingway: It worked for a long time. The sea heals. The woods heal. There is a purity in physical exhaustion that silences the mind. When you are tracking a kudu in the green hills of Africa, you cannot worry about your bank account or your critics. You are present. It is… mindfulness, I think you call it now?

Danny: We do.

Hemingway: We called it hunting. But yes, it worked. The problem is, eventually, your body fails. You get old. You get injured. You survive two plane crashes in Africa in two days—which I did, by the way. And when the body breaks, and you can’t hunt, and you can’t box, and you can’t drink… then what? All you have left is the silence. And if you haven’t learned how to fill that silence with anything but action, you are empty. That’s what happened to me. The container broke.

Danny: So, for the modern man who loves the gym, or loves video games, or loves fixing cars—your advice isn’t “stop doing that and go to therapy.” It’s “don’t let that be your only coping mechanism.”

Hemingway: Exactly. Build the bench. Catch the fish. But know how to talk, too. Have two weapons. I only had one. I had the sword. I didn’t have the shield.

Danny: I want to ask you about the “man up” culture. You are often quoted by the “manosphere” types today—guys who think society has become too feminine, too soft. They look at your photo—the turtle-neck, the beard—and they post it with captions like “Reject Modernity, Embrace Tradition.” What do you think when you see men using your image to tell other men not to have feelings?

Hemingway: I think they are misreading the books. Have they read The Sun Also Rises? Jake Barnes is impotent. He is physically incapable of “being a man” in the sexual sense. He is broken. The whole book is about people wandering around, lost, drinking to forget that they are shattered. It’s not a celebration of strength; it’s a tragedy about broken people trying to find dignity.

Have they read A Farewell to Arms? The hero deserts the army! He walks away from the war to be with the woman he loves. He chooses love over duty. That is the ultimate rejection of the “Strongman” military code.

People cherry-pick the bullfights and forget the tears. If you think I was just about being tough, you’re reading the dust jacket, not the book.

Danny: That is a brilliant correction. You were writing about the cost of masculinity, not just the glory of it.

Hemingway: I was writing about the struggle to be a decent human being in a world that wants to grind you down. Sometimes that looks like shooting a lion. Sometimes it looks like ordering another bottle of wine because you’re afraid to go to sleep in the dark.

Danny: Let’s talk about the “Gender Paradox of Suicide.” Women seek help; men die. You died. Your father died by suicide. Your brother. It’s a generational curse in your family. Do you think it was biological? Or was it this script—this refusal to bend?

Hemingway: It was both. The blood is the blood. Chemistry is real. You can’t write your way out of a chemical imbalance, any more than you can box your way out of diabetes. But the script… the script made it impossible to ask for a life raft. When my father did it, I was angry at him. I called him a coward. I wrote that he “died in a trap.”

Danny: And then?

Hemingway: And then I found myself in the same trap. The trap isn’t life. The trap is the refusal to admit that the trap exists. If I had said, “I am sick. I am not Papa. I am Ernest, and I am sick,” maybe I would have lived. But Papa couldn’t be sick. Papa could only be dead. The legend had to remain intact.

Danny: That’s the “Facade” we talked about. The mask eats the face.

Hemingway: The mask eats the face. That’s a good line. Did you write that?

Danny: I think I just came up with it.

Hemingway: Not bad. A bit flowery. Cut the “the.” “Mask eats face.” Stronger.

Danny: Still editing. I love it. Okay, let’s pivot a bit. I want to ask about women. You had a reputation for being… difficult. Misogynistic, some critics say. But you also wrote some incredibly complex female characters, like Brett Ashley. How do you view the role of women in the “Strongman” paradox? Do they reinforce it?

Hemingway: Women are the mirrors. We look at them to see if we are men. If she looks at you with admiration, you exist. If she looks at you with pity, you dissolve. That puts a terrible burden on the woman. She has to be the audience for your one-man show.

Brett Ashley… she was stronger than any of the men in that book. She was the one who drove the action. She was the one who refused to be pinned down. Maybe I was jealous of her. Men often hate the freedom in women that they deny themselves.

Danny: “Men hate the freedom in women that they deny themselves.” That explains so much of the anger we see online today. Men see women being emotional, supportive, vocal, and flexible, and instead of joining them, they attack them.

Hemingway: It’s envy dressed up as superiority. “Look at those emotional women,” the man says, while his own heart is rotting from isolation.

Danny: So, Ernest, imagine you are standing in front of a classroom of young men today. 18, 20 years old. They are confused. They hear “masculinity is toxic” on one side, and “be an Alpha male” on the other. They are scared to speak. They are scared to fail. What do you tell them?

Hemingway: I’d tell them that the only true nobility is in being superior to your former self, not to other men. I’d tell them that courage is not the absence of fear. Courage is being terrified and doing the right thing anyway. And sometimes, the “right thing” is looking your friend in the eye and saying, “I am hurting.”

I’d tell them to write. Not for publication. But for themselves. Get the poison out. Put it on paper so you don’t have to carry it in your chest.

And I’d tell them that being strong includes being strong enough to be gentle. A rock can break a window. But water can shape the rock. Be the water.

Danny: “Be the water.” That sounds very Bruce Lee of you, Ernest.

Hemingway: Bruce Lee? Who is that? Another writer?

Danny: A fighter. You’d like him. He had a lot to say about fluidity.

Hemingway: Sounds like a smart man.

Danny: Before we wrap up, I have to ask a question for the writers listening. We talked about how your style influenced the “Strongman” voice. Do you regret stripping the language down so much? Do you think English lost something when we stopped writing like Dickens and started writing like you?

Hemingway: Dickens was paid by the word. I was paid by the impact. I don’t regret the style. It was necessary. We needed to clear the throat of literature. It was choked with adjectives and adverbs and nonsense. We needed to get to the bone.

But… maybe we stayed at the bone too long. A skeleton is strong, but it’s not warm to hug. Maybe it’s time to put some meat back on the language. It’s okay to use a word like “magnificent” or “sorrow” once in a while. Just don’t overdo it.

Danny: I’ll try to keep my adverbs in check.

Hemingway: You used “incredibly” earlier. I let it slide.

Danny: I noticed. Thank you for your restraint.

Hemingway: Grace under pressure, Danny.

Danny: Ernest, this has been… honestly, it’s been a highlight of my career. To hear you deconstruct your own myth is a gift.

Hemingway: Don’t get sentimental on me.

Danny: I won’t. I’ll just say thank you.

Hemingway: You’re welcome. Now, about this “dry studio.” You know the interview is over. The recording light is off?

Danny: Technically, yes.

Hemingway: Good. There’s a bar down the street. It’s called “The Library.” Terrible name, but they serve a decent daiquiri. I’m buying.

Danny: I thought you said you didn’t have any money?

Hemingway: I’m a ghost, Danny. I don’t pay. You pay. But I’m “buying” in spirit.

Danny: That sounds like a paradox I can live with. Let’s go.

Hemingway: After you.

0 Comments