- The Great Ego Inflation of the Twentieth Century

- The Cart Before the Horse: Correlation vs. Causation

- The Dark Side of Feeling Great: Narcissism and Aggression

- The Participation Trophy Generation and the Anxiety of “Specialness”

- The Trap of Contingent Self-Esteem

- The Better Alternatives: Self-Compassion and Self-Efficacy

- Breaking the Mirror

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis

- Let’s Discuss

- Let’s Play & Learn

The Great Ego Inflation of the Twentieth Century

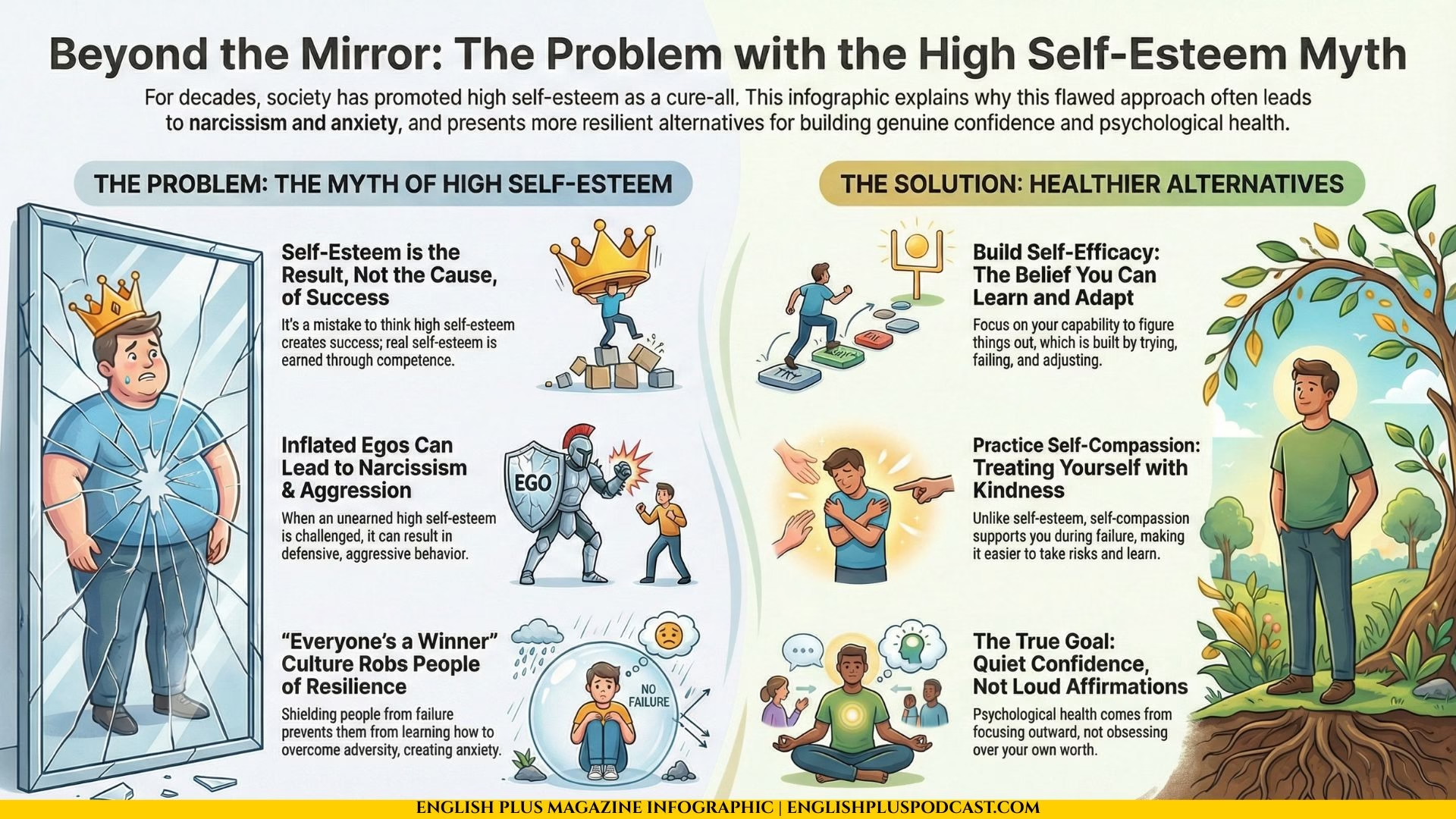

We have been sold a bill of goods. For decades, the cultural narrative in the West, particularly in the United States, has been singing a monotonous, hypnotic tune: if you want to fix society, if you want to fix your kids, and if you want to fix yourself, you just need to love yourself more. We treat self-esteem like it is some kind of psychological Windex—just spray it on everything from bad grades to criminal behavior, and suddenly, the world will sparkle. We have bought into the idea that high self-esteem is the golden ticket to happiness, success, and moral fortitude.

But here is the uncomfortable truth that might make you rethink that “Employee of the Month” plaque or the participation trophies gathering dust in your attic: self-esteem is not the panacea we were promised. In fact, when it is unearned or disconnected from reality, it can be downright dangerous. We are drowning in a culture of “I’m special because I exist,” and frankly, it is making us miserable, anxious, and arguably more narcissistic.

Let’s rewind a bit. This obsession didn’t just appear out of thin air. It was engineered. In the late 1980s, a task force in California actually signed legislation based on the premise that raising self-esteem would solve major social problems like teen pregnancy, drug abuse, and crime. The logic seemed sound on the surface: people who feel good about themselves don’t do bad things, right? Wrong. It turns out that some of the most dangerous people in history felt fantastic about themselves. But we will get to the dark side in a moment.

The Cart Before the Horse: Correlation vs. Causation

The fundamental error in the self-esteem movement is a classic mix-up of cause and effect. We look at successful people—CEOs, top athletes, brilliant artists—and we see that they have high self-esteem. We think, “Aha! They are successful because they have high self-esteem.” So, we try to inject that confidence into children or employees, hoping success will follow.

It is completely backward. Most of the time, self-esteem is the result of competence, not the cause of it. You feel good about your math skills because you actually studied, practiced, and aced the test. You didn’t ace the test just because you stood in front of a mirror reciting affirmations about how you are a math genius. When we artificially inflate self-esteem without the scaffolding of actual achievement or skill, we create a hollow shell. We create people who feel they deserve success without putting in the work, and when the world inevitably pushes back—because the world doesn’t care about your affirmations—that hollow shell cracks.

The Dark Side of Feeling Great: Narcissism and Aggression

Here is where it gets really interesting, and slightly terrifying. If the “Self-Esteem is Always Good” myth were true, then bullies would universally suffer from low self-esteem. That is the story we tell children, isn’t it? “Don’t worry about the bully; he is just insecure inside.”

Research suggests otherwise. Many bullies actually have blindingly high self-esteem. They think they are superior, and their aggression comes out when that superiority is threatened. This brings us to the concept of “threatened egotism.” There is a specific type of high self-esteem that is fragile and defensive. When a person with this mindset faces criticism or failure, they don’t reflect; they attack. They lash out to protect their inflated self-image.

Think about the most difficult people you have ever worked with. Are they the quiet, humble ones who maybe doubt themselves a little? Or are they the ones who are absolutely convinced of their own brilliance and view any constructive feedback as a personal declaration of war? High self-esteem, when it borders on narcissism, prevents learning. If you already think you are perfect, why would you ever try to improve? It kills growth. It kills curiosity. And it kills relationships because, let’s face it, nobody wants to be friends with someone who is in love with their own reflection.

The Participation Trophy Generation and the Anxiety of “Specialness”

We have to talk about the kids. We raised an entire generation on the philosophy that everyone is a winner. We removed the sting of failure from childhood. We thought we were protecting them, shielding their fragile egos from the harsh realities of competition. But what did we actually do? We robbed them of resilience.

Resilience is built through exposure to difficulty. It is like an immune system for your psyche. If you live in a bubble, your immune system never learns to fight. If you are never allowed to lose, you never learn that losing isn’t fatal. You never learn how to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and try again. Instead, you grow up terrified of failure because it is this unknown, monstrous thing.

This creates a paradox: by trying to make kids feel good all the time, we have made them incredibly anxious. The pressure to be “special” and “extraordinary” is crushing. Average is treated like an insult. But statistically, most of us are average in most things, and that is perfectly fine. The relentless pursuit of high self-esteem turns life into a constant performance review where you are terrified that one slip-up will expose you as a fraud.

The Trap of Contingent Self-Esteem

The problem isn’t just high self-esteem; it is contingent self-esteem. This is when your self-worth is tethered to external outcomes. “I am a good person if I get the promotion.” “I am worthy if I get X number of likes on this photo.” “I am valuable if my partner loves me.”

This is a rollercoaster existence. You are on top of the world one minute and in the depths of despair the next, all depending on things you cannot control. It is an exhausting way to live. You become a slave to validation. You stop doing things because you enjoy them or because they are meaningful, and you start doing them solely for the hit of dopamine that comes from approval. You become a puppet, and the world holds the strings.

True psychological health isn’t about thinking you are amazing. It is about not thinking about yourself so much in the first place. It is about having a self-worth that is non-contingent. You exist; therefore, you have value. Period. Whether you win the gold medal or trip over your own shoelaces at the starting line, your fundamental worth as a human being remains unchanged. That is a stability that high self-esteem can never provide.

The Better Alternatives: Self-Compassion and Self-Efficacy

So, if we toss out the self-esteem myth, what do we replace it with? We shouldn’t swing to the other extreme of self-loathing. The answer lies in two concepts: Self-Compassion and Self-Efficacy.

Self-efficacy is the belief in your ability to figure things out. It is different from self-esteem. Self-esteem says, “I am great.” Self-efficacy says, “I can learn this.” It is focused on action and capability, not inherent status. It is built through doing, trying, failing, and adjusting. It is robust because it is based on evidence, not feelings.

Then there is self-compassion, a concept championed by researchers like Dr. Kristin Neff. Unlike self-esteem, which requires you to be better than others to feel good, self-compassion just requires you to be human. It is the ability to treat yourself with the same kindness you would offer a friend when things go wrong.

When you fail—and you will fail—self-esteem abandons you. It says, “You failed? You must be a loser. I’m out of here.” Self-compassion steps in and says, “Ouch, that hurt. But it is okay. Everyone messes up. What can we learn from this?” It provides a safety net that allows you to take risks without the paralyzing fear of shame. It de-couples your performance from your identity.

The Freedom of Being Ordinary

There is a profound liberation in letting go of the need to be special. When you accept that you are a flawed, messy, average human being just like everyone else, the pressure lifts. You don’t have to prove your worth every time you walk into a room. You can just be.

You can admit when you are wrong because being wrong doesn’t destroy your identity. You can admire other people’s success without feeling threatened because life isn’t a zero-sum game of who is the “best.” You can connect with people more deeply because you are presenting your authentic self, cracks and all, rather than a polished, curated image designed to garner applause.

Breaking the Mirror

The mythology of self-esteem was a well-intentioned experiment, but the results are in, and they are lackluster at best and destructive at worst. We need to smash the mirror. We need to stop gazing at our own reflections, obsessing over whether we are good enough, smart enough, or pretty enough.

Real confidence is quiet. It doesn’t need to shout affirmations. It is the quiet knowing that you can handle what life throws at you. It is the understanding that you are not the center of the universe, and that is a good thing. The world is vast, complex, and fascinating. When we stop obsessing over our own self-esteem, we finally free up the mental energy to look outward, to engage with the world, to help others, and to do work that actually matters. And ironically, that is usually when we start feeling pretty good about ourselves—not because we tried to, but because we forgot to try.

Reading Comprehension Quiz

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Let’s dive right into the language we used to deconstruct this myth, because talking about psychology and human behavior requires nuance. If you use the wrong word, you end up sounding like a pop-psychology paperback from the checkout aisle. We want to sound like we know what we are talking about.

We started with the word panacea. We said self-esteem is not the panacea we were promised. This is a beautiful word that comes from Greek, meaning “cure-all.” In the old days, alchemists looked for a panacea to cure every disease. In modern life, we use it to describe a solution that people think will fix everything, but usually won’t. You might say, “Technology is useful, but it’s not a panacea for the education system’s problems.” It implies skepticism. It says, “Don’t be naive; this problem is complex.”

Then we talked about scaffolding. We mentioned “artificially inflating self-esteem without the scaffolding of actual achievement.” Scaffolding is literally the temporary structure used to support a building while it is being constructed. In a metaphorical sense, especially in education or psychology, it refers to the support systems necessary to build a skill or a trait. You can’t just have the roof (the high self-esteem) without the beams and pillars (the hard work). You could use this at work: “We need to provide more scaffolding for the new interns before we give them a major project.”

We used the phrase contingent. This is a powerhouse word in this context. We talked about contingent self-esteem. If something is contingent, it depends on something else. It is conditional. “Our picnic is contingent on the weather.” When we talk about self-worth, if it is contingent, it is unstable. It means you are only okay if x, y, or z happens. Using this word shows you understand the relationship between variables.

We discussed the scarcity of resilience in a bubble. But let’s look at the word resilience itself. It’s overused, but we defined it as an “immune system for your psyche.” Resilience isn’t just toughness; it is the ability to bounce back. Elasticity. Think of a rubber band versus a piece of glass. Both are solid, but only one is resilient. Glass is hard, but it shatters. The rubber band yields and returns. In your life, you want to be the rubber band.

We mentioned narcissism. Now, be careful with this one. We often throw it around to mean “selfish.” But in our text, we used it to describe a pathological inflation of self-importance. We linked it to threatened egotism. This is a great phrase to keep in your pocket. It explains why some arrogant people explode when criticized. Their ego is under threat. If you are in a meeting and your boss snaps because you corrected a typo, you can think to yourself, “Ah, threatened egotism.” (But maybe don’t say it out loud).

We used the term zero-sum game. We said life isn’t a zero-sum game of who is best. In game theory, a zero-sum game is one where for me to win, you must lose. Poker is a zero-sum game. The pot is fixed. But happiness, success, and self-worth are generally non-zero-sum. My success doesn’t have to subtract from yours. Using this phrase makes you sound analytical and logical.

We talked about validation. We said people become slaves to validation. Validation is the recognition or affirmation that a person or their feelings are valid or worthwhile. It is that stamp of approval. We all need it a little, but the text warns against needing it to survive. “He is seeking validation” is a polite way of saying someone is fishing for compliments or acting out of insecurity.

We discussed introspection. We implied that people with high, fragile self-esteem lack it. Introspection is the examination of one’s own mental and emotional processes. It is looking inward. It is the opposite of looking in the mirror to admire yourself; it is looking inside to understand yourself. “She has a lot of introspection” is a high compliment for someone who is self-aware.

We used the word fortitude. We mentioned “moral fortitude.” Fortitude is courage in pain or adversity. It’s an old-school word. It sounds stronger than just “bravery.” Bravery is running into a burning building. Fortitude is enduring a chronic illness with grace, or sticking to your principles when everyone is mocking you. It implies endurance.

Finally, let’s look at nuance. We mentioned that the truth requires nuance. Nuance is a subtle difference in or shade of meaning, expression, or sound. It is the grey area. The myth of self-esteem lacks nuance because it says “All self-esteem is good.” The reality is nuanced: “Some is good, some is bad, it depends on the source.” People who can appreciate nuance are generally smarter and more reasonable than those who see everything in black and white.

Now, let’s move to the speaking part. How do we sound authoritative without sounding like the narcissists we just warned against? The key is Epistemic Humility. That is a fancy term for admitting what you don’t know.

Ironically, saying “I don’t know” or “I could be wrong, but…” can make you sound more confident than someone who blusters. However, there is a trap. We often use “I think,” “I feel,” or “In my opinion” as filler words that weaken our points.

“I think this plan is dangerous.” -> Weak.

“This plan presents several significant risks.” -> Strong.

The second sentence is still an opinion, but it is stated as an observation of reality. It invites the listener to look at the risks, rather than just agreeing with your feelings.

Speaking Challenge:

I want you to record yourself for 60 seconds. Pick a topic you disagree with popularly—maybe you hate coffee, or you think superhero movies are boring. I want you to make your case without using the phrases “I think,” “I believe,” “I feel,” or “In my opinion.”

Instead of saying “I think coffee tastes like burnt dirt,” say “The flavor profile of coffee is remarkably similar to burnt dirt.” See the difference? You are shifting from subjective validation to objective description. It forces you to use better vocabulary and stronger arguments. Try it. It is harder than it sounds, but it will instantly elevate your speaking presence.

Vocabulary and Speaking Quiz

Grammar and Writing

We are shifting gears to the written word. Writing about yourself is one of the hardest things to do because we are trapped in our own heads. We either brag too much (the self-esteem trap) or we whine too much (the victim trap). We need to find the balance, and that balance is found in honesty and structural precision.

The Writing Challenge: The Failure Resume

In the spirit of debunking the self-esteem myth, we are not going to write about your greatest triumph. We are going to write a Failure Resume.

A normal resume lists your degrees, your awards, and your successful projects. A Failure Resume lists the schools that rejected you, the jobs you didn’t get, the projects that crashed and burned, and the relationships you messed up.

I want you to write a 300-500 word narrative piece focusing on one specific failure from your past. But here is the catch: you cannot write it to garner pity (“poor me”), and you cannot write it to show how great you are for overcoming it (“I’m a hero”). You must write it clinically and analytically. What happened? What mistake did you make? What was the specific lesson learned?

Grammar Focus: The “But-Therefore” Transition

Bad writing is often just a list of “And then… and then… and then.” This is boring. Good writing involves causality and conflict. The creators of South Park (who are surprisingly good storytellers) use the rule of “Therefore and But.”

Instead of: “I studied hard and I took the test and I failed.”

Try: “I studied hard, but I focused on the wrong material; therefore, I failed the test.”

The “But” introduces conflict/failure. The “Therefore” introduces the consequence/result.

In your Failure Resume, I want to see this structure.

“I wanted the promotion badly, but I was too arrogant to ask for feedback on my presentation; therefore, the client walked away.”

Grammar Focus: Concessive Clauses for Nuance

To write about failure without sounding bitter, you need Concessive Clauses. These are clauses that start with Although, Even though, Despite, or In spite of. They allow you to hold two opposing thoughts in your head at the same time.

- “Although I was qualified for the job, I completely misread the room during the interview.”

- “Despite my best efforts to prepare, the project failed due to a lack of communication.”

This grammar structure signals maturity. It shows you can acknowledge the good (I was qualified) while accepting the bad (I misread the room). It prevents the writing from being black-and-white.

Grammar Focus: Modals of Deduction for Retrospective

When analyzing the past, we need to use Modals of Deduction (Past Form). These are: should have, could have, might have, would have.

- “I should have listened to my mentor.” (Regret/Advice)

- “I could have prepared more thoroughly.” (Possibility/Ability)

- “The outcome might have been different if I had been more humble.” (Uncertainty/Speculation)

Be careful not to overuse “would have” to rewrite history fantastically. Use “should have” to identify the specific error in judgment. This is the grammar of accountability.

Writing Tips for Vulnerability

- Kill the Adverbs: When we are insecure, we use adverbs to prop up our emotions. “I was incredibly sad.” “It was totally unfair.” Cut them. “I was sad.” “It was unfair.” The bluntness hits harder.

- Specifics over Generalities: Don’t say “I messed up at work.” Say “I sent the email to the wrong ‘David’ and leaked the budget to a competitor.” The specific detail makes it real and, frankly, a bit funny. Humor is a great way to diffuse the tension of failure.

- The Pivot: End the piece with the pivot. Don’t end on the failure. End on the change in behavior. “Now, I double-check the recipient field three times before I hit send.”

This challenge is uncomfortable. That is the point. High self-esteem runs away from discomfort. Self-efficacy leans into it. By writing this down, you are taking the power away from the failure. You are turning a skeleton in your closet into a specimen in a museum—something to be studied, not feared.

Grammar and Writing Quiz

Critical Analysis

Now, let’s take a step back and critique our own article. I’m putting on my “Expert/Skeptic” hat. While we made a compelling case against the “Self-Esteem Movement,” we might have swung the pendulum too far in the other direction.

First, we completely glossed over the role of Socioeconomic Status and Trauma. It is very easy for a comfortable, middle-class person to say, “You don’t need self-esteem; just work hard!” But for marginalized communities or children growing up in abusive environments, a basic sense of self-worth (self-esteem) might be the only thing keeping them alive. For someone who is told by society daily that they are worthless, “high self-esteem” isn’t narcissism; it is a radical act of survival. We missed that nuance. We treated self-esteem as a luxury item for the privileged, rather than a psychological necessity for the oppressed.

Secondly, we focused heavily on Western, individualistic culture. The whole concept of “Self-Esteem” is incredibly weird to many Eastern or collectivist cultures. In Japan, for example, self-criticism (hansei) is often valued more than self-promotion. The goal is to fit in and improve the group, not to stand out and feel “special.” By framing the entire debate around whether the individual feels good or bad, we are still trapped in a very Western paradigm. Maybe the problem isn’t how we value the self, but that we are obsessed with the self at all.

Third, we attacked “participation trophies,” which is a bit of a cliché. Is the trophy really the problem? Or is it the Parental Anxiety behind the trophy? We blamed the movement for making kids anxious, but maybe the kids are anxious because the world is actually more competitive and expensive than it was in the 1970s. Blaming “too much self-esteem” might be a convenient way to ignore structural economic issues that make young people feel insecure.

Finally, we proposed “Self-Compassion” as the solution. But can self-compassion become an excuse for mediocrity? “Oh, I didn’t finish the report, but I’m being compassionate to myself.” There is a danger there, too. Any psychological tool can be weaponized by the ego to avoid work. We need to be careful not to just swap one feel-good buzzword for another without demanding the discipline that actually builds character.

Let’s Discuss

Here are some questions to spark a fire in the comments section (or at your dinner table). These aren’t safe questions. They are meant to poke at your assumptions.

Is “Imposter Syndrome” actually a good sign?

We usually treat Imposter Syndrome as a disorder to be cured. But what if it’s just a realistic assessment of the gap between your skills and your goals? Does feeling like a “fraud” keep you humble and working hard? When does it cross the line from motivating to paralyzing?

Should we bring back public ranking in schools?

Many schools stopped posting class rankings to protect students’ feelings. But the real world ranks us constantly (salaries, promotions, sports). Are we doing children a disservice by hiding their relative standing? Or does public shaming kill potential before it can grow?

Is “Fake it ’til you make it” valid advice, or is it lying?

This advice basically tells you to project high self-esteem before you have the competence to back it up. Is this a necessary strategy for career advancement, or is it the root cause of incompetent leadership and fraud (think Theranos)?

Can you love others if you hate yourself?

The old saying goes “You can’t love anyone until you love yourself.” Is that true? Or is it just pop-psychology nonsense? Can’t a person be self-loathing but still be an incredibly devoted, loving parent or partner? Maybe focusing on loving others is the cure for self-hatred.

Is Social Media the cause of the narcissism epidemic, or just the mirror?

We blame Instagram and TikTok for making us vain. But maybe we were always this vain, and the technology just gave us a platform? If we took away the “Like” button tomorrow, would our self-esteem issues vanish, or would they just manifest differently?

Is “Self-Care” becoming a toxic form of selfishness?

The concept of self-care (bubble baths, cutting out “toxic” friends) is huge right now. But at what point does “protecting my peace” become “avoiding accountability and abandoning people who need me”? Where is the line between self-preservation and narcissism?

If you could permanently delete your “ego,” would you?

Imagine a pill that removes your sense of self-importance. You no longer care if you are respected or admired, but you also might lose the drive to achieve great things. Would you take it? Is ambition tied inextricably to the ego?

0 Comments