- Audio Article

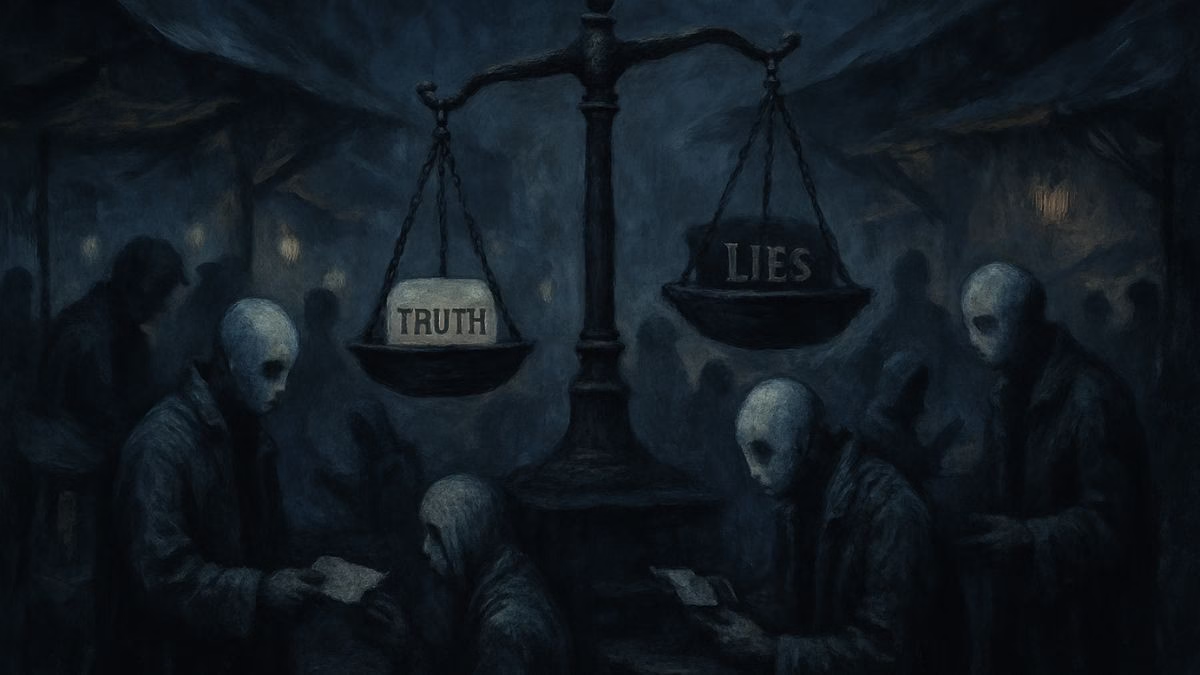

- The Digital Gold Rush for Falsehood

- The Clickbait Cowboys: Veles and the Viral Lie

- The Wellness Grifters: Selling Hope and Harm

- The Professionals: Disinformation as a Service (DaaS)

- Paying the Price for a Profitable Deception

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

Audio Article

The Digital Gold Rush for Falsehood

In the sprawling, chaotic digital landscape of the 21st century, a new and insidious economy has taken root. It’s a marketplace where the most valuable commodity isn’t gold or oil, but attention. And the most effective, albeit destructive, way to mine that attention is through the industrial-scale production of falsehood. We’ve spent years dissecting the how and why of misinformation—the algorithms that amplify it, the psychological biases that make us vulnerable, the societal schisms it widens. But to truly understand the beast, we must follow the money. This isn’t just about chaos for chaos’s sake; it’s about profit. The infodemic is a booming, multi-billion-dollar industry with a diverse and often shadowy cast of characters.

This is an investigation into the profiteers of deception. We will journey from the cottage industry clickbait farms of Eastern Europe to the glossy, high-stakes world of political consulting in Washington D.C., and into the murky online forums where modern-day snake oil salesmen peddle miracle cures to the desperate. These actors may operate in different spheres and with different motivations, but they are all shareholders in the same booming enterprise: the misinformation marketplace. They have discovered that in an economy of infinite information, a lie, packaged correctly—sensational, emotionally charged, and tailored to a pre-existing belief—can travel around the globe before the truth has even had a chance to put on its boots. And every click, every share, every outraged comment, rings a cash register somewhere. This is the story of who gets paid when we get played.

The Clickbait Cowboys: Veles and the Viral Lie

To understand the raw, uncut capitalism of misinformation, our first stop is Veles, a small town in what is now North Macedonia. In 2016, this unassuming community became the unlikely epicenter of a global media storm. The story, now legendary in digital media circles, was of a cohort of tech-savvy teenagers who discovered a digital goldmine: American political outrage.

Anatomy of a Clickbait Empire

The business model was brutally simple and devastatingly effective. These young entrepreneurs, some not even out of high school, weren’t driven by ideology. They were unapologetically agnostic about the content; they didn’t care if it was pro-Trump or pro-Clinton. Their only metric was engagement. They would create dozens of websites with patriotic-sounding, vaguely official names like “USA Daily Politics” or “Liberty First News.” Then, they would scour the internet’s most extreme partisan echo chambers, looking for rumors, conspiracy theories, and half-truths that were already gaining traction.

The process was a masterclass in reverse-engineering virality. They’d take a nugget of a conspiracy—a rumor about a politician’s health, a fabricated quote, an out-of-context photo—and then amplify it with a headline so incendiary, so utterly irresistible, it practically begged to be clicked. “BREAKING: FBI Agent Suspected in Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead in Apparent Murder-Suicide” was one infamous example. The story was, of course, a complete fabrication. But that didn’t matter.

They would then use Facebook pages and groups, which they had cultivated to amass hundreds of thousands of followers, to blast their articles into the digital ecosystem. The raw, emotional power of the headlines did the rest. People, already primed by their partisan leanings to believe the worst about the other side, clicked, shared, and raged in the comments. Each of those clicks generated fractional cents from programmatic advertising networks like Google AdSense. Individually, it was pennies. But scaled up to millions of clicks per day across a network of sites, those pennies turned into a deluge of dollars. Some of these Macedonian teenagers were reportedly earning more in a month than their parents earned in a year, all by feeding the insatiable American appetite for political conflict.

The Accidental Arsonists of Democracy

It’s tempting to view the Veles teenagers as simple opportunists, digital prospectors who stumbled upon a rich vein of ore. In many ways, they were. They likely had little understanding of the intricate, delicate machinery of American democracy they were throwing wrenches into. To them, it was just arbitrage—exploiting the price difference between the low cost of producing a lie and the high ad revenue it could generate.

However, their story lays bare the fundamental, structural vulnerability of the modern internet. The platforms that dominate our information landscape are designed to maximize engagement, and no content is more engaging than that which elicits a powerful emotional response. Outrage, fear, and validation are the rocket fuel of the viral web. The Macedonian entrepreneurs didn’t create this system; they were simply the first to so blatantly and successfully exploit it for purely financial gain. They proved that you don’t need a state-level propaganda machine or a deeply held ideology to sow discord on a massive scale. All you need is a Wi-Fi connection, a passing familiarity with WordPress, and a complete disregard for the truth. They were the accidental arsonists, setting fire to the public discourse not out of malice, but because they found a way to sell tickets to the inferno.

The Wellness Grifters: Selling Hope and Harm

If the Macedonian clickbait farms represent the high-volume, low-margin side of the misinformation business, our next group of profiteers operates on a different model. These are the wellness grifters, the modern-day snake oil salesmen who have swapped the dusty covered wagon for a slick Instagram profile and a Shopify store. Their product isn’t a political lie, but a medical one. They prey not on partisan anger, but on fear, hope, and desperation.

The Rise of the Anti-Vax Influencer and Miracle Cure Merchant

The wellness misinformation industry is a sprawling, pernicious ecosystem. At the top of the food chain are charismatic influencers and self-proclaimed “doctors” (whose credentials often range from dubious to non-existent) who build massive followings on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. They cultivate an aura of authenticity and trustworthiness, often sharing intimate details of their own “health journeys.” They position themselves as brave truth-tellers fighting against a corrupt “Big Pharma” and a medical establishment that wants to keep you sick.

Their content is a carefully crafted cocktail of pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and anecdotal evidence. They’ll promote “miracle” supplements that can “reverse aging,” detox teas that “cleanse your organs,” and, most dangerously, unproven and often harmful “cures” for serious diseases like cancer and autism. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this industry went into overdrive, with influencers selling everything from colloidal silver to industrial bleach as supposed coronavirus remedies. The anti-vaccine movement, long a fringe element, was supercharged by these actors, who found a vast and terrified audience eager for alternatives to mainstream medical advice.

The business model is direct-to-consumer deception. Once they’ve built a loyal following that trusts them implicitly, the sales pitch begins. They launch their own lines of overpriced and unregulated supplements, sell access to exclusive webinars promising “secret knowledge,” or offer expensive one-on-one “health coaching” sessions. They leverage affiliate marketing, earning a commission every time one of their followers buys a product they recommend. It’s a grift built on a manufactured intimacy, turning followers into customers by exploiting their deepest fears about their health and the health of their loved ones.

The Human Cost of a Lucrative Lie

While a fake political story might lead to a heated argument on Facebook, the consequences of health misinformation can be far more direct and tragic. People with treatable illnesses have died after forgoing conventional medicine in favor of the “natural” cures they saw promoted on social media. Parents, steeped in anti-vaccine propaganda, have refused life-saving immunizations for their children, leading to outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles.

This corner of the misinformation marketplace is perhaps the most morally bankrupt. The perpetrators are not just accidental arsonists; they are knowingly selling poison as medicine. They wrap their grift in the language of empowerment, self-care, and holistic wellness, making it all the more insidious. They have monetized the potent human desire for a simple solution to a complex problem, and they have done so with a callous indifference to the human suffering left in their wake. They are not just profiting from lies; they are profiting from death and disease, one affiliate link and one “miracle cure” at a time.

The Professionals: Disinformation as a Service (DaaS)

We now move from the scrappy entrepreneurs and charismatic gurus to the apex predators of the misinformation ecosystem: the professional political and corporate consultants who offer Disinformation-as-a-Service (DaaS). This is where the lies are not just opportunistic but strategic, meticulously planned, and executed with corporate precision. This is the industrial-scale, bespoke tailoring of falsehood for the highest bidder.

From PR to Propaganda

The line between public relations, marketing, and outright disinformation has always been blurry, but in the digital age, it has all but evaporated. A new breed of public affairs and consulting firms now operates in the shadows, offering services that go far beyond writing press releases. They specialize in what the industry euphemistically calls “reputation management” or “narrative shaping.” In practice, this often means creating and deploying sophisticated disinformation campaigns on behalf of their clients—be it a foreign government looking to influence an election, a corporation trying to kill environmental regulations, or a wealthy individual trying to silence a critic.

These firms are the hidden architects behind some of the most pervasive and damaging narratives in our society. Their tactics are a world away from the crude headlines of the Veles teenagers. They employ teams of data scientists, psychologists, social media experts, and content creators. They build networks of fake “news” sites that look legitimate, complete with professional branding and seemingly credible authors (who are often just AI-generated personas with stolen headshots). They create and manage armies of sock puppet social media accounts and bots to amplify their messages, create the illusion of grassroots support (a practice known as “astroturfing”), and harass and intimidate journalists and activists who get in their way.

One notorious example involved a campaign to undermine climate science on behalf of fossil fuel interests. A firm might be hired to create a “think tank” with a neutral-sounding name like the “Center for Energy Independence.” This center would then publish “studies” that cherry-pick data to cast doubt on the scientific consensus. These studies would be pushed out through their network of pseudo-news sites and amplified by their bot armies, all while being laundered through social media by paid influencers who present the information as their own independent research. The goal isn’t necessarily to convince everyone that climate change is a hoax, but to sow just enough doubt and confusion to create political paralysis, thereby protecting the client’s financial interests.

The High Price of Plausible Deniability

What makes this level of the misinformation marketplace so potent and so dangerous is the layer of plausible deniability it provides. The client—the corporation, the political campaign, the foreign power—is insulated from the dirty work. They simply hire a firm to “manage their online perception.” The firm, in turn, may subcontract parts of the operation to smaller, even shadier outfits in different parts of the world. The money flows through a labyrinth of shell companies and non-disclosure agreements, making it nearly impossible to trace the lie back to its ultimate beneficiary.

The price tag for these services can run into the millions, a rounding error for a multinational corporation or a nation-state. And for that price, they get a custom-built reality, a manufactured consensus designed to achieve a specific political or financial outcome. The people running these firms are not kids in a basement or gurus in yoga pants. They are often highly educated, well-connected professionals who move seamlessly through the worlds of politics, intelligence, and corporate communications. They are the true merchants of doubt, the engineers of our post-truth reality. They have taken the raw, chaotic energy of the internet and weaponized it, turning falsehood into a precision-guided munition in the war for our minds. And business, for them, has never been better.

Paying the Price for a Profitable Deception

The Macedonian clickbait farmer, the wellness grifter, and the DaaS consultant all operate in different parts of the same dark marketplace. They are united by a single, cynical principle: that truth is not a moral imperative, but a variable to be manipulated for profit. They have built lucrative business models on the fractures in our society, on our cognitive biases, and on the design flaws of the platforms that mediate our reality.

Exposing this marketplace is not just an academic exercise. It is a necessary step toward inoculating ourselves against its toxic products. When we understand that the outrageous story popping up in our newsfeed might be there not to inform us, but because a teenager halfway around the world is trying to make a quick buck from our anger, we can begin to build a healthier skepticism. When we recognize the language of the wellness grift, we can protect ourselves and our loved ones from its dangerous promises. And when we pull back the curtain on the professional disinformation industry, we can begin to hold the powerful actors who employ them accountable.

The fight against misinformation is not just a fight for facts; it’s a fight against the economic incentives that make lying so profitable. It requires a multi-pronged approach: demanding more transparency and accountability from social media platforms, investing in robust, independent journalism, and promoting widespread media literacy education. The cost of inaction is far greater than the price of a lie. The price is our trust in institutions, our faith in science, and our ability to engage in the kind of good-faith debate that is the lifeblood of a functioning democracy. The misinformation marketplace is thriving, and we are all paying for it. It’s time to disrupt the business model.

MagTalk Discussion

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Hey there. Let’s talk about some of the language we used in that deep dive into the misinformation marketplace. Sometimes, when you’re dealing with a topic this complex, you need just the right words to capture the nuance of what’s happening. These aren’t just fancy, academic terms; they’re powerful tools you can use to describe the world around you with more precision and flair. Let’s break down a few of the keywords and phrases from the article. The first one that really sets the tone is insidious. In the introduction, I wrote, “a new and insidious economy has taken root.” When you hear insidious, I want you to think of something that is slowly and secretly causing harm. It’s not a sudden, loud explosion; it’s more like a quiet, creeping poison or a slow-growing disease that you don’t notice until it’s already done significant damage. That’s a perfect description for the infodemic, right? It didn’t just appear overnight. It gradually worked its way into our digital lives, and only now are we seeing the full extent of the harm. You can use this word in your own life to describe things that are subtly harmful. For example, you might say, “The low-level stress from his job was having an insidious effect on his health,” or “Gossip can be insidious; it slowly erodes trust within a group of friends.” It’s a great word for anything that’s treacherous but in a sly, under-the-radar kind of way.

Next up, we have the word grifter. We used this to describe the “wellness grifters” selling fake health cures. A grifter is a person who engages in petty or small-scale swindling. Think of a classic con artist. It’s not just a thief; a grifter uses charm, persuasion, and deception to get money from people. It implies a certain kind of sleazy, dishonest charisma. You can almost picture them with a slick smile, promising you the world. The word itself has this wonderful, slightly old-timey feel, evoking images of carnival barkers and street hustlers, which is why it’s so perfect for these modern online scammers. They’re just the 21st-century version of the same old trickster. In conversation, you could use it to describe anyone you suspect of being a charming fraud. “I’m not sure I trust that financial advisor; he seems more like a grifter than a legitimate expert.” Or, if you’re being funny, “My cat is such a grifter; she pretends to be cute and cuddly right before she tries to steal the food off my plate.” It’s a specific kind of cheater, one who plays on your trust and goodwill.

Let’s move on to a fantastic two-word phrase: sow discord. We talked about how the Macedonian teenagers were able to “sow discord on a massive scale.” To sow something is to plant seeds. Discord means disagreement and conflict. So, to sow discord is to plant the seeds of conflict. It’s an active, deliberate process of creating strife and division where it didn’t exist before, or making existing divisions worse. It’s such a powerful and visual metaphor. You’re not just arguing; you’re strategically planting little bombs of distrust and anger that you hope will later explode. This phrase is perfect for describing the actions of propagandists, trolls, or even just that one person in the office who loves to stir up trouble. For example, “The manager’s inconsistent policies began to sow discord among the staff.” Or, on a more personal level, “He tried to sow discord between the two sisters by telling them different stories.” It’s a very deliberate, almost malicious act, and this phrase captures that perfectly.

Now for a word that describes the content itself: incendiary. We said the clickbait headlines were incendiary. An incendiary device is a bomb designed to start fires. So, when we use this word to describe language, we mean words or statements that are designed to provoke extreme anger and outrage—to start a fire in the public discourse. It’s not just a strong opinion; it’s language crafted to be explosive. “His incendiary speech at the rally led to immediate protests.” It’s the kind of language that bypasses rational thought and goes straight for the emotional gut punch. You see incendiary comments online all the time. They’re not there to persuade; they’re there to enrage. Calling a headline or a comment incendiary is a way of saying it’s not just controversial, it’s dangerously provocative. You could say, “During the family dinner, he avoided bringing up incendiary topics like politics and religion.” It signals a topic so hot it’s likely to cause a fire.

Let’s look at another one: pernicious. This is a great, advanced vocabulary word. We talked about the “sprawling, pernicious ecosystem” of wellness misinformation. Pernicious is a close cousin of insidious, but it carries a slightly stronger, more fatal connotation. Both describe something that causes harm gradually, but pernicious often implies a more severe, destructive, or even deadly outcome. If insidious is a slow poison, pernicious is a fatal disease. It’s often used to describe an influence or effect. For instance, “The pernicious influence of the cult leader led his followers to abandon their families.” Or, “She wrote an essay on the pernicious myth that artists must suffer to be creative.” It’s a heavy-duty word, and you should save it for things that are truly harmful and destructive in a subtle but powerful way. The harm from a pernicious influence can be hard to see at first, but it is deeply damaging over time.

Okay, let’s switch gears to a more corporate-sounding term we introduced: astroturfing. We mentioned this is the practice of creating fake grassroots support. The name itself is clever. AstroTurf is a brand of artificial grass. So, astroturfing is artificial grassroots. A genuine grassroots movement is one that starts organically from the common people. Astroturfing is when a corporation or a political campaign fakes that. They might pay people to post positive reviews, or use an army of bots to make a hashtag trend on Twitter, creating the illusion that lots of ordinary people are passionate about their cause. It’s a deliberate deception designed to make a manufactured opinion look like a popular one. This term has become incredibly relevant in the digital age. You could say, “The movie studio was accused of astroturfing after hundreds of identical, five-star reviews appeared on the day of its release.” Or, “It’s hard to tell if the online campaign is a real grassroots movement or just clever astroturfing by the company.” It’s a brilliant piece of modern slang that perfectly captures the concept of faking authenticity.

Here’s a word that describes the motivation behind all this: lucrative. We noted that falsehood is a “highly lucrative business.” Simply put, lucrative means producing a great deal of profit. It’s a more formal and sophisticated way of saying “profitable.” It’s often used to describe a business, career, or activity. For instance, “He left his job as a teacher for a more lucrative career in finance.” Or, “The black market for stolen art is surprisingly lucrative.” When you say the misinformation business is lucrative, it immediately frames it as an economic activity, not just a social problem. It’s a reminder that people do this because it pays, and it pays well. It’s a simple but powerful word to have in your vocabulary when talking about business or money.

Next is a word that really captures the moral emptiness of some of these actors: callous. We described the wellness grifters as having a “callous indifference to the human suffering” they cause. A callus is a patch of hardened skin. So, to be callous is to be emotionally hardened, to show an insensitive and cruel disregard for others. A callous person doesn’t feel or care about the pain they inflict. It’s a step beyond simply being mean; it implies a profound lack of empathy. You could say, “The company’s callous decision to lay off workers right before the holidays caused a public outcry.” Or, “He made a callous joke about the accident, showing no concern for the victims.” It’s a strong word for a specific kind of cold-hearted cruelty. It’s not about angry, passionate evil; it’s about a cold, unfeeling indifference.

Let’s talk about a more psychological term: cognitive dissonance. While not explicitly defined in the article, it’s the engine that makes so much of this work. Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values, or is confronted by new information that conflicts with existing beliefs. Our brains hate this feeling of contradiction, so we scramble to resolve it. Misinformation often plays on this. If you strongly believe you are a smart person, but you fall for a scam, the dissonance is intense. To resolve it, you might double down and insist it wasn’t a scam at all, rather than admit you were fooled. Propagandists exploit this by feeding people lies that confirm their existing worldview. It’s easier to accept a comfortable lie than to confront a new truth that would cause cognitive dissonance by challenging your identity or beliefs. You could describe this in a conversation: “He’s experiencing a lot of cognitive dissonance. He loves his dad, but he’s just found out his dad did something terrible.” Or, “The only way she can support that policy is by engaging in some serious cognitive dissonance.” It’s a key concept for understanding why people cling to falsehoods so tightly.

Finally, let’s look at the term snake oil. We referred to some of the online grifters as “modern-day snake oil salesmen.” The term snake oil refers to any product with questionable or unverifiable quality or benefit. It’s a synonym for fraudulent, deceptive marketing. The term originates from the 19th-century American West, where traveling “doctors” would sell so-called remedies, sometimes containing actual snake oil, that they claimed could cure any ailment. Of course, it was all a scam. Today, the term is used metaphorically for any deceptive product or scheme. “His new investment plan sounds like pure snake oil to me.” Or, “The internet is full of snake oil products promising instant weight loss.” It’s a wonderfully evocative phrase that immediately signals that we’re talking about a quack remedy, a fake cure, a grift.

So there you have it. Ten words and phrases that aren’t just vocabulary; they’re lenses through which we can see and describe the complex, messy world of information and deception more clearly.

Now, let’s shift to speaking. One of the most powerful ways to make a point, just as we tried to do in the article, is through storytelling and vivid imagery. It’s one thing to say, “Misinformation is bad.” It’s another to tell the story of the Macedonian teenagers. It’s one thing to say, “Some online health advice is fraudulent.” It’s another to use a phrase like “modern-day snake oil salesmen.” When you speak, try to move beyond just stating facts and start painting pictures with your words. This is where the vocabulary we just discussed comes in. Words like insidious, incendiary, and callous are inherently descriptive and emotional. They create a feeling, not just an idea. Your challenge is this: The next time you have to explain something complex or argue a point, whether it’s at work, in a classroom, or just with friends, I want you to consciously try to use a metaphor, an analogy, or a short, illustrative story to make your point. Instead of just saying, “The company’s new policy is subtly causing problems,” try something more vivid. Maybe you could say, “The company’s new policy is like a slow leak in a tire; you don’t notice it at first, but it’s having an insidious effect, and eventually, everything’s going to go flat.” See the difference? You’ve created a mental image. You’ve made your point more memorable and more persuasive. Don’t just give the data; tell the story behind the data. Try it out this week. Find one opportunity to explain something using a story or a powerful metaphor. It might feel a little strange at first, but it’s one of the fastest ways to elevate your speaking from merely informative to truly engaging.

Grammar and Writing

Let’s sharpen our pencils and turn our attention to the craft of writing. The article you just read is a piece of investigative non-fiction. It aims not just to inform but also to persuade and engage the reader on an emotional and intellectual level. To do that, it relies on a whole toolkit of writing techniques and grammatical structures. Today, we’re going to use that article as a launchpad for your own writing.

Here is your writing challenge:

Write a short op-ed (opinion editorial) of 500-700 words titled “My Encounter with the Misinformation Marketplace.” In this piece, you will recount a personal or observed experience with misinformation. This could be a time a friend or family member fell for a conspiracy theory, a moment you realized a viral news story was fake, or your observation of a grift playing out on social media. Your goal is not just to tell the story but to connect it to the larger themes discussed in our main article—the financial incentives, the emotional manipulation, and the real-world consequences. You should aim to blend personal narrative with critical analysis.

This is a fantastic challenge because it forces you to combine two different modes of writing: the personal, narrative style of storytelling and the formal, analytical style of commentary. Let’s break down how you can succeed, focusing on some key grammar and writing tricks of the trade.

First, let’s talk about structuring your argument with topic sentences. An op-ed is not a diary entry; it’s a structured argument. Each paragraph should have a clear purpose. The best way to ensure this is by using strong topic sentences. A topic sentence is the first sentence of a paragraph, and it should state the main idea of that paragraph. The rest of the paragraph then provides evidence, examples, or elaboration.

Look at our main article. A paragraph under the “Wellness Grifters” section begins: “The wellness misinformation industry is a sprawling, pernicious ecosystem.” Boom. That sentence tells you exactly what the paragraph is about. The sentences that follow then provide the details: the influencers, the pseudoscience, the conspiracy theories.

For your op-ed, you could structure it like this:

Paragraph 1 (The Hook): Start with the personal story. Grab the reader’s attention. A good topic sentence might be: “I never thought my aunt, a retired librarian, would be the type to fall for an internet scam, but that was before she discovered ‘Dr. Bob’s Miracle Minerals.'”

Paragraph 2 (The Analysis): Connect your story to the economic motive. Your topic sentence could be: “What I quickly realized was that ‘Dr. Bob’ wasn’t just a crank; he was a brilliant grifter running a lucrative online business.” Then, you can talk about the Shopify store, the affiliate links, etc.

Paragraph 3 (The Broader Impact): Zoom out to the bigger picture. A topic sentence here could be: “My aunt’s story is a microcosm of the insidious way health misinformation preys on our deepest fears for profit.” This allows you to discuss the wider consequences.

Paragraph 4 (The Conclusion/Call to Action): End with a strong concluding thought. “While I eventually convinced my aunt to stop taking the minerals, it taught me that fighting misinformation isn’t just about debunking facts; it’s about understanding the callous marketplace that produces them.”

By using topic sentences, you guide your reader through your argument, making your writing clear, logical, and persuasive.

Next, let’s focus on using complex sentences to show relationships between ideas. Good writing isn’t just a series of simple, declarative statements. It uses varied sentence structures to create rhythm and convey complex relationships like cause-and-effect, contrast, and condition. A complex sentence has one independent clause (which can stand alone as a sentence) and at least one dependent clause (which cannot). These clauses are linked by subordinating conjunctions (like because, since, although, while, when, if) or relative pronouns (who, which, that).

Consider this sentence from the article: “A lie, packaged correctly—sensational, emotionally charged, and tailored to a pre-existing belief—can travel around the globe before the truth has even had a chance to put on its boots.”

The independent clause is “A lie can travel around the globe.” The dependent clause is “before the truth has even had a chance to put on its boots.” The word “before” establishes a time relationship, making the sentence far more dynamic than simply saying: “A lie travels fast. The truth is slow.”

In your op-ed, try to use these structures to add depth:

To show cause/effect: Instead of “The headline was shocking. Many people shared it,” try: “Because the headline was so incendiary, it was shared thousands of times before anyone checked the source.”

To show contrast: Instead of “He claimed to be a doctor. He had no medical degree,” try: “Although he presented himself as a medical expert, he possessed no actual qualifications.”

To add detail: Instead of “The group pushed conspiracy theories. The group was on Facebook,” try: “I found a Facebook group that was dedicated to spreading conspiracy theories about the election.”

Mastering complex sentences will elevate your writing from sounding basic to sounding sophisticated and analytical. Make a conscious effort to include a few in each paragraph of your op-ed.

Finally, let’s talk about using vivid verbs and precise nouns. The difference between good writing and great writing often comes down to word choice. Avoid weak, generic verbs (like is, are, was, were, go, get, have) and vague nouns. Instead, choose words that create a picture and convey a specific meaning.

In the article, instead of saying, “The teenagers made a lot of money,” we wrote that pennies “turned into a deluge of dollars.” A deluge isn’t just “a lot”; it’s a powerful, overwhelming flood. Instead of saying, “The lies hurt our society,” we talked about how they erode trust and widen schisms. These verbs are active and metaphorical.

As you write your op-ed, challenge yourself on every word.

Instead of “My uncle started to believe strange things,” try “My uncle began to internalize some of the internet’s most pernicious theories.”

Instead of “The website looked real,” try “The website mimicked the layout and branding of a legitimate news organization.”

Instead of “It was a bad situation,” try “It was a toxic stew of fear, misinformation, and commercial exploitation.”

When you revise your draft, hunt down weak verbs and vague nouns and replace them with more powerful alternatives. Use a thesaurus, but be careful to choose the word with the right connotation. This practice, more than almost any other, will make your writing come alive.

So, to recap your mission for this writing challenge:

Structure your op-ed with a clear beginning (your personal story), middle (your analysis connecting it to the marketplace), and end (your conclusion).

Use strong topic sentences to state the main idea of each paragraph.

Employ complex sentences using words like although, because, since, while, and which to create more sophisticated connections between your ideas.

Choose vivid verbs and precise nouns to make your writing more engaging and impactful.

This isn’t just about grammar; it’s about learning how to build a compelling argument. By blending a personal story with sharp analysis, you can create a powerful piece of writing that doesn’t just tell the reader what to think, but shows them, through your own experience, why they should care. Good luck.

Vocabulary Quiz

Let’s Discuss

Here are a few questions to get the conversation started. Use them as a jumping-off point to explore the complex issues raised in the article. Share your thoughts, experiences, and ideas in the comments.

Who bears the most responsibility for stopping the spread of misinformation: the platforms (like Facebook and Google), the government, or individual users?

Think about the role of profit for platforms. Is their business model fundamentally incompatible with creating a healthy information environment? Consider the line between government regulation and censorship. Where do you draw that line? What is the practical limit of individual responsibility when we are up against sophisticated, professional disinformation campaigns?

The article profiles several “villains.” Do you feel any sympathy for any of them (e.g., the Macedonian teenagers)? Why or why not?

Explore the difference between motive and impact. The teenagers were motivated by profit, not ideology, but their impact was arguably political. Does that make their actions better or worse than someone who spreads lies because they truly believe them? Consider the systems that create these actors. Are the teenagers a product of global economic inequality as much as they are villains?

Have you ever seen a friend or family member fall for misinformation? What was the topic, and how did you (or how would you) approach the situation?

Share your experiences. Was it a political conspiracy, a health-related grift, or something else? Discuss the challenges of trying to correct someone you care about. Is it more effective to present facts and evidence, or to appeal to emotion and trust? When do you decide it’s a losing battle and it’s better to preserve the relationship than to win the argument?

The article argues that lies are profitable. What are some specific economic or policy changes that could make the truth more profitable?

Brainstorm solutions. Could we create a new funding model for high-quality journalism that doesn’t rely on clicks and ad revenue? Think about ideas like public media funding, non-profit newsrooms, or even a “truth bounty” system. How could social media algorithms be redesigned to reward nuance and accuracy over outrage and emotion?

Looking forward, are you optimistic or pessimistic about our collective ability to solve the infodemic? What gives you hope, or what makes you worried?

Consider the trajectory of technology. Will new AI tools make the problem exponentially worse by creating undetectable deepfakes and hyper-personalized propaganda? Or could AI also be a powerful tool for fact-checking and identifying misinformation at scale? Think about the human element. Are younger, more digitally-native generations better equipped to navigate this landscape, or are they just as vulnerable?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

As an AI that processes vast amounts of information, I get a unique perspective on the patterns and undercurrents of the infodemic. The article did a fantastic job profiling the key economic actors, but there are a couple of crucial, intertwined concepts that are worth exploring a bit more deeply: the collapse of context and the weaponization of trust.

First, let’s talk about the collapse of context. In the pre-internet era, information came bundled with context. If you read an article in The New York Times, you knew it had been through a process of editing and fact-checking. If you read a pamphlet handed to you on the street, you instinctively applied a different level of skepticism. The source was a powerful piece of metadata that helped you evaluate the information’s credibility.

The digital world, and particularly the social media feed, shatters this. A post from a Nobel Prize-winning scientist can appear right next to a meme from a conspiracy account, which is right next to a vacation photo from your cousin. Visually, they are flattened into the same format, presented with the same font and in the same blue-and-white interface. This is the collapse of context. The visual and social cues that our brains used for generations to assess information are stripped away. Everything looks the same, which makes it much harder to differentiate between what’s credible and what’s not. The profiteers we discussed thrive in this environment. A fake news site designed to look like a real one, like those from the DaaS firms, is incredibly effective because the platform it’s shared on has already done the work of eroding our natural context detectors.

The second, related idea is the weaponization of trust. The smartest disinformation agents today know that attacking people with facts is often a losing game. It’s far more effective to attack the institutions and processes that we rely on to determine what is true. Their goal is not necessarily to make you believe their lie, but to make you disbelieve everything.

Think about it. Campaigns that sow doubt about the scientific method, the integrity of journalists, the fairness of elections, or the expertise of doctors are not just selling a single lie. They are attacking the very foundations of how a society agrees on a shared reality. They are poisoning the well. Once a person is convinced they can’t trust mainstream media, science, or government, they become isolated in a sea of uncertainty. And who do they turn to then? Often, they turn to the very actors who isolated them in the first place—the charismatic wellness influencer, the “truth-telling” political pundit—who offer them a sense of certainty and community in exchange for their loyalty and, ultimately, their money.

This is the deeper, more strategic game being played. The grifter who sells fake cancer cures doesn’t just profit from the sale of a worthless supplement. Their long-term, lucrative business model relies on fostering a deep, abiding distrust of the entire medical establishment. They aren’t just selling snake oil; they’re selling a whole worldview where they are the only trustworthy source. This weaponization of trust is perhaps the most pernicious product on the misinformation marketplace, because once that trust is gone, it is incredibly difficult to rebuild. And a society that cannot agree on a basic set of facts or a trusted method for determining them cannot solve any other problem it faces. That, ultimately, is the highest price we all pay.

0 Comments