Vocabulary Preview

- Apocryphal: (of a story or statement) of doubtful authenticity, although widely circulated as being true.

- Anachronism: A thing belonging or appropriate to a period other than that in which it exists, especially a thing that is conspicuously old-fashioned.

- Malign: To speak about (someone) in a spitefully critical manner.

- Exacerbate: To make (a problem, bad situation, or negative feeling) worse.

- Veracity: Conformity to facts; accuracy.

- Ostentatious: Characterized by vulgar or pretentious display; designed to impress or attract notice.

- Tumultuous: Excited, confused, or disorderly.

- Callous: Showing or having an insensitive and cruel disregard for others.

- Corroborate: To confirm or give support to (a statement, theory, or finding).

- Scapegoat: A person who is blamed for the wrongdoings, mistakes, or faults of others, especially for reasons of expediency.

Listen

Or Read

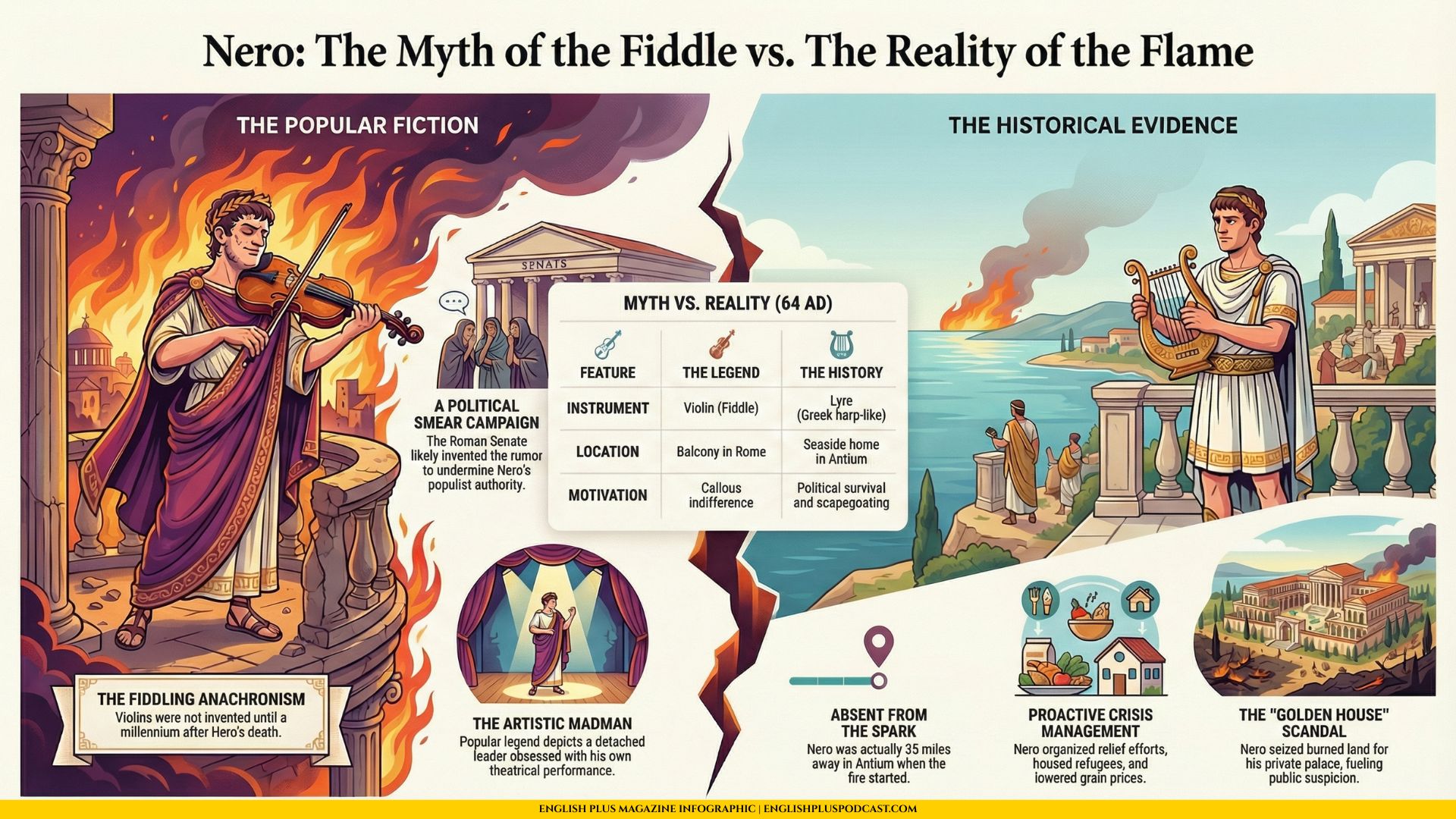

Nero fiddled while Rome Burned.

We all know the image, don’t we? It is perhaps one of the most enduring scenes in Western history: the mad emperor Nero, draped in purple silk, standing on a balcony with a manic glint in his eye. Below him, the greatest city on earth is being consumed by an inferno, screaming citizens fleeing for their lives, while he calmly tucks a violin under his chin and plays a little tune. It is the ultimate picture of a callous leader, a man so detached from reality and so obsessed with his own artistic pretensions that he turns a tragedy into a recital. It’s a powerful story. It tells us everything we need to know about absolute power corrupting absolutely. There is just one tiny, nagging problem with this cinematic masterpiece of a scene: it is almost certainly complete nonsense.

Let’s start with the most obvious blooper in this historical screenplay. The idea of Nero playing a “fiddle” or a violin is a glaring anachronism. Violins wouldn’t be invented for another thousand years or so. If Nero played anything, it would have been a lyre, a harp-like instrument popular in ancient Greece and Rome. But focusing on the instrument misses the bigger point because the veracity of the entire event is shaky at best. According to the most reliable Roman historian of the time, Tacitus, Nero wasn’t even in the city when the first spark ignited in the Circus Maximus in 64 AD. He was roughly 35 miles away in Antium, his seaside hometown, probably enjoying the cool breeze while Rome began to smoke.

So, if he wasn’t there to serenade the flames, what did he actually do? Contrary to the popular belief that he celebrated the destruction, historical records suggest Nero acted surprisingly responsibly. Upon hearing the news, he rushed back to the capital to organize relief efforts. He opened his private gardens to house the homeless refugees and lowered the price of grain to prevent famine. These aren’t the actions of a lunatic arsonist; they are the actions of a leader trying to manage a tumultuous crisis. However, doing a good job doesn’t always make for a good story, especially when you have enemies who are determined to malign your character for eternity.

And boy, did Nero have enemies. The Roman Senate despised him. To them, he was a populist demagogue who bypassed their authority to appeal directly to the common people. The image of the “fiddling Nero” likely started as a rumor spread by these political rivals to undermine his authority. They whispered that while the people suffered, the Emperor was singing “The Sack of Ilium” in his private stage costume, comparing Rome’s fall to Troy’s. It was the ancient equivalent of a smear campaign or a viral fake news tweet. These rumors were apocryphal, born from hatred rather than fact, but they stuck because they confirmed what the elite already felt about him: that he was a dangerous, theatrical weirdo.

Now, we can’t let Nero off the hook entirely. While he might not have started the fire or played music during it, his actions after the blaze certainly helped exacerbate the public’s suspicion. Once the rubble was cleared, Nero didn’t just rebuild the homes of the poor; he seized a massive chunk of prime real estate in the city center to build his Domus Aurea, or “Golden House.” This wasn’t just a house; it was an ostentatious palace complex with an artificial lake, spinning dining rooms, and a colossal 100-foot bronze statue of himself. It was a bit tone-deaf, to say the least. Imagine a modern president seizing a disaster zone to build a private golf course. It didn’t look good. The people, seeing this lavish construction rise from the ashes of their homes, began to wonder if maybe, just maybe, the Emperor did want the city to burn so he could have a blank canvas for his architectural ego.

Realizing that public opinion was turning against him and that the rumors of arson were becoming dangerous, Nero did something truly horrific that no amount of myth-busting can absolve him of. He needed a scapegoat. He found one in a small, misunderstood religious sect that was already viewed with suspicion by the Romans: the Christians. Nero accused them of starting the fire to deflect the blame from himself. This led to a brutal wave of persecution where Christians were rounded up and executed in grisly ways. This part of the history is not a myth; it is a tragedy born from a leader’s desperate need to control the narrative.

So, why does the “fiddling” story persist two thousand years later? Why do we ignore the relief efforts and focus on the lyre? Perhaps it’s because history is rarely written by the neutral; it is written by the victors and the survivors. The historians who chronicled Nero’s life—Suetonius and Cassius Dio—wrote decades after his death and relied heavily on the biased accounts of the Senate. They didn’t have video evidence or neutral journalists to corroborate their claims. They were storytellers crafting a moral lesson about the dangers of tyranny. The fiddling Nero is a caricature, a useful monster that serves as a warning.

But as critical thinkers, we have to look past the caricature. We have to understand that truth is often messier than fiction. Nero wasn’t a cartoon villain; he was a complex, flawed, and likely paranoid ruler who did some terrible things, but “fiddling while Rome burned” wasn’t one of them. Unraveling this myth reminds us to question the sensational headlines we see today. It teaches us that just because a story confirms our biases about a “bad person,” it doesn’t make it true. It forces us to ask: Who is telling the story? What is their agenda? And are we buying into a narrative just because it’s entertaining?

So, here is a question for you to chew on: In our modern world of 24-hour news cycles and social media, who are the “Neros” we are quick to believe the worst about without checking the facts? And what “fiddles” do we imagine they are playing while we aren’t looking? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below!

Word Power

Alright, let’s take a closer look at the linguistic toolkit we just used to dismantle that ancient rumor. These are powerful words that can really sharpen how you talk about news, history, or even office gossip.

First up is Apocryphal. This is a fantastic word for a story that everyone tells, everyone believes, but likely never happened. The story of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree? Apocryphal. It implies that the story has a mythical quality to it. You might hear someone say, “That story about the CEO firing someone for wearing the wrong color tie is totally apocryphal.”

Then we have Anachronism. This refers to something that is out of place in time. A movie about the 1800s where an actor is wearing a digital watch is an anachronism. We used it to point out that a fiddle in Ancient Rome is historically impossible. You can also use it metaphorically to describe a person who seems old-fashioned, like, “His views on technology are a total anachronism in this modern startup.”

We talked about how Nero’s enemies wanted to Malign him. To malign is to trash-talk someone with the intent of ruining their reputation. It’s stronger than just “criticize.” If your coworker spreads lies that you’re stealing lunches just to get you fired, they are maligning you.

Exacerbate is a word you need for when things go from bad to worse. It means to aggravate a situation. Scratching a mosquito bite will only exacerbate the itch. In our story, Nero’s fancy palace exacerbated the public’s anger.

We discussed the Veracity of the rumors. Veracity just means truthfulness or accuracy. In the age of fake news, checking the veracity of a headline is a crucial skill. You might ask, “I doubt the veracity of his excuse for being late.”

Nero’s palace was described as Ostentatious. This is for when someone is showing off their wealth or status in a loud, tacky way. A gold-plated car is ostentatious. It’s not just rich; it’s screaming, “Look at me, I’m rich!”

The crisis in Rome was Tumultuous. This describes a situation that is chaotic, noisy, and full of upheaval. A tumultuous relationship is one with lots of fighting and drama. A tumultuous storm is violent and destructive.

We called the image of the fiddling Nero Callous. If someone is callous, they have developed a thick skin to the suffering of others; they just don’t care. Walking past someone who fell down without helping them is callous.

We noted that historians couldn’t Corroborate the rumors. To corroborate is to provide evidence to support a claim. If you tell the police you were at the movies during the crime, they will check your ticket stub to corroborate your alibi. It’s a key word for critical thinking.

Finally, the classic Scapegoat. This is the person or group that gets blamed for everything when things go wrong, usually unfairly. When a football team loses, the coach often becomes the scapegoat, even if the players played badly. Nero used the Christians as a scapegoat for the fire.

Speaking Tips & Challenge

Now, how do we weave these into your daily conversation without sounding like a history textbook?

- Veracity is great for skepticism. Instead of saying “Is that true?”, try “I’m not sure about the veracity of that claim.”

- Exacerbate is perfect for problem-solving. “Let’s not exacerbate the problem by panicking.”

- Corroborate works well in professional settings. ” Can anyone corroborate these figures before we present them?”

Your Speaking Challenge:

I want you to think of a movie you saw recently, or a book you read. Was there a villain? Was there a misunderstanding?

Try to describe the plot to yourself or a friend using at least three of our new words.

Example: “The villain was totally callous; he tried to malign the hero with apocryphal stories so he could take over the kingdom.”

Give it a try! It’s a fun way to make your storytelling more precise and engaging.

0 Comments