- MagTalk Audio Podcast

- The Illusion of Connection

- The Evolutionary Imperative

- The Cognitive vs. The Emotional

- The Architecture of the Echo Chamber

- The Cost of Disconnection

- The Radical Act of Listening

- Empathy for the Unlikable

- Reclaiming Our Humanity

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis

- Let’s Discuss

- Let’s Play & Learn

MagTalk Audio Podcast

The Illusion of Connection

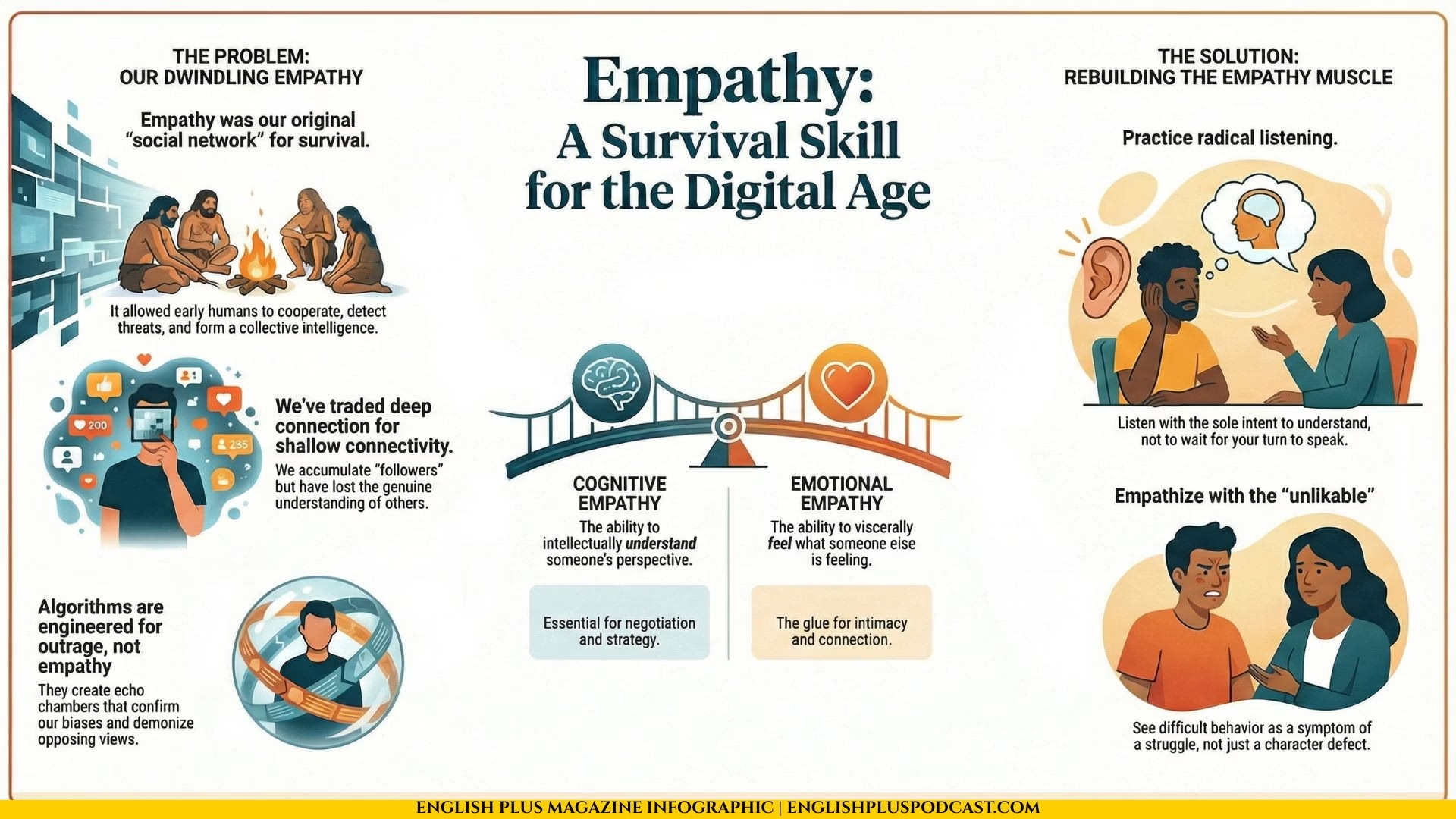

We live in an era where we are technically more connected than any civilization in human history. You can pull a device from your pocket and instantly video chat with someone in Timbuktu, scroll through the minute-by-minute thoughts of a stranger in Tokyo, or read an op-ed written ten minutes ago in London. Theoretically, this hyper-connectivity should have ushered in a golden age of understanding. We have a front-row seat to the lives, struggles, and joys of billions. Yet, looking around, it feels like we are drifting further apart, locked in sleek, glass-walled silos of our own making. We are shouting into the digital void, hearing only the echoes of our own opinions bouncing back at us.

This is the modern paradox. We have traded depth for breadth. We accumulate “friends” and “followers” like currency, yet we find ourselves bankrupt when it comes to genuine, visceral understanding of what it means to be someone else. We are suffering from an empathy deficit. And before you roll your eyes and think this is just another soft-hearted plea for everyone to “be nice,” let’s clarify something immediately: Empathy is not about being nice. It is not about agreeing with everyone. It is not about holding hands and singing songs around a campfire while the world burns.

Empathy is a cognitive and emotional mechanism that allowed our ancestors to organize, hunt, and survive in hostile environments. It is a strategic advantage. It is the ability to run a simulation in your brain of another person’s internal state. When we lose that ability, or when we voluntarily surrender it for the comfort of tribalism, we aren’t just becoming jerkier versions of ourselves; we are dismantling the very evolutionary scaffolding that keeps society from collapsing into chaos.

The Evolutionary Imperative

Let’s rewind the clock a few hundred thousand years. You are a hominid on the Savannah. You are not the strongest creature there. You don’t have the claws of a lion, the speed of a cheetah, or the thick skin of a rhino. What you have is a brain capable of complex social processing. If you cannot look at a fellow tribe member and intuitively understand that their grimace means “danger is approaching from the tall grass,” you die. If you cannot empathize with your offspring’s cry of hunger, your lineage ends.

Empathy was the original internet. It was the network that connected individual minds to form a collective intelligence. It allowed us to cooperate, to share resources, and to protect the vulnerable. It wasn’t a luxury; it was a survival skill. Those who lacked it were ostracized, and in the prehistoric world, solitude meant death.

Fast forward to today. The sabre-toothed tigers are gone, replaced by corporate mergers, political polarization, and algorithmic rage bait. The physical threat of immediate death from solitude is lower, but the social threat is higher than ever. Yet, we seem to have convinced ourselves that empathy is a weakness. We mistake hardness for strength. We view the ability to detach and remain unaffected as a badge of honor. We look at the “other”—the person across the political aisle, the neighbor with the loud dog, the driver who cut us off—not as a complex human with a history and a nervous system, but as an obstacle. A non-player character in the video game of our life.

This dehumanization is dangerous. When we shut down our empathy centers, we revert to binary thinking: Good vs. Evil, Us vs. Them. It feels safe because it’s simple. Nuance is exhausting. Understanding why someone holds a view you find abhorrent takes cognitive caloric energy. Hating them is efficient. It burns cheap fuel. But that cheap fuel produces toxic fumes that are slowly suffocating our collective culture.

The Cognitive vs. The Emotional

It is important to distinguish between the types of empathy because they are not created equal, and they serve different functions. Psychologists generally divide empathy into two main buckets: cognitive empathy and emotional (or affective) empathy.

Cognitive empathy is the ability to intellectually understand someone else’s perspective. It’s perspective-taking. It’s the Sherlock Holmes ability to look at a situation and deduce, “Ah, this person is angry because they feel disrespected.” You don’t necessarily feel their anger, but you understand the mechanics of it. This is a crucial skill for negotiation, debate, and strategy. It allows you to anticipate moves.

Emotional empathy is the visceral reaction. It’s when you see someone slam their finger in a car door and you physically cringe, clutching your own hand. It’s the mirroring of emotion. This is the glue of intimacy. It’s what makes us rush to help a crying child or comfort a grieving friend.

The problem we face today is a mismatch. We have people who are high in cognitive empathy but use it for manipulation—understanding exactly what makes people tick so they can exploit it. Think of the quintessential cold-blooded corporate climber or the political demagogue. On the other hand, we have people so overwhelmed by emotional empathy—so flooded by the suffering of the world presented to them on 24-hour news cycles—that they burn out. They shut down completely to preserve their sanity. This is “compassion fatigue.”

The sweet spot—the survival skill zone—is a balance. It is the ability to engage cognitive empathy to understand the context of someone’s behavior, while allowing enough emotional empathy to care about the outcome, without being swept away by the tide of their feelings. It is a disciplined engagement.

The Architecture of the Echo Chamber

We cannot talk about the empathy deficit without addressing the elephant in the server room: the algorithm. Social media platforms are engineered to maximize engagement, and it turns out that outrage is the most engaging emotion of all. Empathy is slow; outrage is fast. Empathy requires pause; outrage demands reaction.

When you are fed a steady diet of content that confirms your existing biases and demonizes those who think differently, your empathy muscles atrophy. You are never forced to do the heavy lifting of understanding a counter-argument. You are told, explicitly and implicitly, that the “other side” is not just wrong, but morally bankrupt. And you cannot empathize with moral bankruptcy. You shouldn’t, right?

This is where the trap snaps shut. Once you decide a group of people is beneath empathy, you give yourself permission to treat them with cruelty. You see this in comment sections every day. People who would hold a door open for a stranger in real life will type the most vitriolic, hateful things to a stranger online. The screen acts as an empathy blocker. It strips away the non-verbal cues—the tone of voice, the facial expression, the hesitation—that usually trigger our empathetic response. We are left with cold text, and we project our worst assumptions onto it.

We are becoming insular. We retreat into digital enclaves where everyone agrees with us, creating a feedback loop of validation. It feels good. It feels like belonging. But it is a fragile, hollow belonging because it is based on shared hatred rather than shared understanding.

The Cost of Disconnection

The societal cost of this deficit is obvious: polarization, gridlock, conflict. But the personal cost is just as high. A life without empathy is a lonely life. When you cannot connect with the experiences of others, you are trapped inside your own head. You become the protagonist of a story where everyone else is just a supporting character or a villain. That is a small, claustrophobic world to live in.

Furthermore, a lack of empathy makes us terrible problem solvers. Most real-world problems—in business, in relationships, in politics—are people problems. They are messy, illogical, and emotional. If you try to solve them with pure logic, ignoring the human element, you will fail. You cannot optimize a marriage with a spreadsheet. You cannot manage a team solely with KPIs. You need to understand the fears, motivations, and insecurities driving the people involved.

There is also a physical toll. Loneliness and social isolation, which are byproducts of low empathy, are linked to a host of health issues, from cardiovascular disease to a weakened immune system. We are social animals. When we are disconnected, our bodies react as if we are under threat. Our cortisol levels spike. We stay in fight-or-flight mode. Empathy is the soothing signal that tells our nervous system, “We are safe. We are connected.”

The Radical Act of Listening

So, how do we rebuild this skill? It starts with the most underrated communication skill in existence: listening. And I don’t mean listening while waiting for your turn to speak. I don’t mean listening to find a flaw in the argument so you can destroy it. I mean listening with the sole intent of understanding.

This is harder than it sounds. It requires you to suspend your judgment. It requires you to bench your ego. You have to accept that you might be wrong, or at least, that your truth is not the only truth. When someone shares an experience that contradicts your worldview, the instinct is to defend. “But that’s not true because…” or “Yeah, but what about…”

Suppress that instinct. Ask questions instead. “What did that feel like?” “How did you come to that conclusion?” “Tell me more about that.” These are the tools of the empathy archaeologist. You are digging for the logic and emotion beneath the surface.

This doesn’t mean you have to agree. You can perfectly understand why someone believes the earth is flat—you can understand their distrust of authority, their need for special knowledge, their community validation—without accepting their geography. But once you understand the why, you are no longer yelling facts at a wall. You are engaging with a human being.

Empathy for the Unlikable

The ultimate test of empathy is not empathizing with the innocent victim or the cute puppy. It is empathizing with the person you find difficult, abrasive, or wrong. It is easy to love the lovable. It is a survival skill to understand the unlovable.

Think of the person at work who makes your life miserable. The micromanager. The gossip. Your narrative is likely: “They are a bad person.” Try to flip the script. What kind of fear drives micromanagement? Usually, it’s a deep-seated insecurity about competence or a loss of control. What drives gossip? A desperate need for connection or status. When you see the behavior as a symptom of a struggle rather than a character defect, your anger often shifts to pity or at least, a detached understanding. You don’t have to invite them to dinner, but you stop letting them rent space in your head. You regain your power.

Reclaiming Our Humanity

We are standing at a crossroads. We can continue down the path of fragmentation, retreating further into our silos, dehumanizing anyone who doesn’t fit our mold. Or, we can choose the harder path. We can choose to be curious. We can choose to be vulnerable. We can choose to see the humanity in the person screaming at us on Twitter.

Empathy is a muscle. If you don’t use it, it withers. But if you exercise it—if you consciously try to see the world through a different set of eyes once a day—it gets stronger. It expands your world. It makes you a better writer, a better partner, a better leader, and yes, a better survivor.

In a world obsessed with artificial intelligence, human empathy is the one thing that cannot be automated. It is our competitive advantage. It is the survival skill of the future. Let’s not lose it.

Reading Comprehension Quiz

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Let’s dive right into the mechanics of the language we used because, frankly, having a survival skill is useless if you can’t articulate it, right? We tossed around some heavy hitters in the article, words that carry a lot of weight and texture. Take the word visceral, for example. We talked about a “visceral understanding” or a “visceral reaction.” This isn’t just about understanding something with your brain; it’s about feeling it in your guts. It comes from “viscera,” referring to your internal organs. So when you use this in real life, you’re describing an emotion so strong it feels physical. If you watch a horror movie and jump, that’s a visceral reaction. If you hear a song that makes you cry immediately, that’s visceral. It’s a great word to use when “strong” or “deep” just doesn’t cut it.

Then we have the concept of being insular. We mentioned retreating into “insular” digital enclaves. Think of an island. To be insular is to be isolated, but usually in a way where you’re ignorant of or uninterested in cultures, ideas, or peoples outside your own little bubble. In a professional context, you might say a company failed because its management was too insular—they weren’t looking at market trends, they were just talking to each other. It’s a sophisticated way of calling someone narrow-minded but pointing to their isolation as the cause.

We also discussed the scaffolding of society. Now, scaffolding is literally those temporary structures you see on the side of buildings under construction. But metaphorically, and how we used it, it refers to the underlying support structures that hold something up. Education, empathy, the justice system—these are the scaffolding of civilization. You can use this when talking about learning, too. Teachers provide scaffolding for students—support that is gradually removed as the student becomes more independent. It implies structure, support, and necessity.

Let’s look at atrophy. We said empathy muscles atrophy. This is a medical term originally—muscles wasting away from lack of use. Borrowing medical terms for social commentary is always punchy. Your skills can atrophy. Your patience can atrophy. It paints a vivid picture of decay and neglect. It suggests that the thing was once strong and healthy but has withered because you got lazy.

We mentioned vitriolic. This is a fantastic word for the internet age. Vitriol is an old name for sulfuric acid. So, vitriolic language is language that burns and corrodes. It’s not just mean; it’s caustic. It’s filled with malice. If you get into an argument and someone gets really nasty, you can describe their response as vitriolic. It sounds much more serious than just saying they were “mean” or “angry.”

Then there’s cognitive. We distinguished between cognitive and emotional empathy. Cognitive relates to the process of thinking, knowing, and remembering. It’s the brain work. You might have a cognitive understanding of why you shouldn’t eat that donut (it’s unhealthy), but an emotional desire to eat it anyway. Using “cognitive” elevates your speech because it specifies where the action is happening—in the intellect, not the heart.

We talked about nuance. Nuance is the subtle difference in or shade of meaning, expression, or sound. It’s the gray area. We live in a black-and-white world, so calling for nuance is asking for detail and complexity. If someone gives you a very simple explanation for a complex problem, you might say, “I think you’re missing some nuance here.” It’s a polite but intellectual way to say, “It’s more complicated than that.”

How about ostracized? We said those without empathy were ostracized. This means to be excluded from a society or group. It comes from ancient Greece where they would literally vote to banish people. In modern life, you can be ostracized from a friend group, a professional community, or a family. It’s a strong word for rejection. It implies a collective decision to push someone out.

We used the term demagogue. A political demagogue. This is a leader who seeks support by appealing to the desires and prejudices of ordinary people rather than by using rational argument. It’s a specific type of manipulator. If you see a leader riling up a crowd by blaming a scapegoat, you are watching a demagogue at work. It’s a powerful political science term that fits perfectly into discussions about empathy deficits.

Finally, let’s look at altruism, or the lack thereof implicit in the article. Altruism is the disinterested and selfless concern for the well-being of others. It’s doing good when no one is watching and you get nothing out of it. It’s the opposite of the “me-first” attitude. You can ask, “Is true altruism possible?” which is a great philosophical debate starter.

Now, let’s shift gears to speaking. Knowing these words is one thing; using them to sound empathetic is another. A huge part of the speaking skill related to empathy is active listening markers. When we speak, we often focus on our output, but in a conversation, your “listening noises” are just as important.

Simple phrases like “It sounds like…” or “What I’m hearing is…” are powerful. They are check-ins. If you say, “It sounds like you felt really ostracized in that meeting,” you are doing two things: you are using a rich vocabulary word (ostracized) and you are validating their feeling. You aren’t saying they were ostracized; you are validating that they felt it. That is a massive distinction.

Another technique is tentative language. Instead of saying “You are wrong,” or “That is bad,” use phrases like “I wonder if…” or “Could it be that…” or “My impression was…” This lowers the defense of the person you are talking to. It signals that you are exploring the truth together, not delivering a verdict.

Here is your challenge, and it’s going to be tougher than you think. I want you to have a conversation today—it can be with a cashier, a friend, or a family member—where you ask three follow-up questions before you share your own opinion or story. Three. Someone says, “I had a terrible day.” You don’t say, “Me too.” You say, “I’m sorry to hear that. What happened?” (Question 1). They tell you. You say, “That sounds incredibly frustration. How did you handle it?” (Question 2). They answer. You say, “Is there anything you can do to fix it tomorrow?” (Question 3). Only then can you talk about yourself. This forces you to engage that cognitive empathy and suppresses the urge to make the conversation about you. It’s a speaking exercise that is actually a listening exercise.

Vocabulary and Speaking Quiz

Grammar and Writing

For this section, we are going to tackle a writing challenge that requires you to be vulnerable, which is the engine of empathy. I want you to write a 300 to 500-word personal essay or op-ed piece about a time you experienced a failure of empathy. Not a time someone was mean to you, but a time you failed to understand someone else, or dismissed them, or judged them too quickly, and realized it later.

This is a powerful prompt because it forces you to embrace the “Unreliable Narrator” concept in non-fiction. You are critiquing your past self. To make this writing successful, we need to look at some specific grammar structures and writing techniques that allow for this kind of reflection.

First, let’s talk about the Subjunctive Mood and Hypotheticals. When you are writing about regret or analyzing past actions, you need to talk about what didn’t happen.

- Structure: “If I had [past participle], I would have [past participle].”

- Example: “If I had taken a moment to look at her face, I would have seen the tears welling up.”

This is the Third Conditional. It is essential for reflective writing. It signals to the reader that you are aware of alternative outcomes. It creates a parallel universe in your writing where you were a better person, contrasting it with the reality where you weren’t.

Next, let’s look at Modal Verbs of Deduction. You are looking back at a situation and trying to understand what the other person was thinking. Since you aren’t a mind reader, you have to guess.

- Keywords: Must have, might have, could have, can’t have.

- Example: “She must have been terrified, but I only saw her silence as arrogance.”

- Example: “He might have been trying to protect me, but I interpreted it as control.”

Using “must have” implies you are almost certain. “Might have” implies possibility. This adds the nuance we talked about earlier. It shows the reader you are actively trying to piece together the puzzle of the other person’s mind.

A critical writing technique for this piece is Show, Don’t Tell applied to internal states.

- Telling: “I was annoyed and didn’t care about his problems.” (Boring, flat).

- Showing: “I checked my watch while he was speaking. I nodded at the right intervals, but my mind was already drafting the email I needed to send.”

The second version shows the lack of empathy through physical action (checking the watch) and internal monologue (drafting the email). It is much more relatable and damning. It allows the reader to judge you, which is what good writing does—it engages the reader’s judgment.

Let’s also discuss Concessive Clauses. These are clauses that start with “Although,” “Even though,” “Despite,” or “While.” They are vital for holding two opposing thoughts in your head at the same time—the definition of cognitive empathy.

- Example: “Even though I knew he was grieving, I couldn’t help but feel irritated by his outburst.”

- Example: “Despite his clear cry for help, I chose to walk away.”

These structures create tension. They admit the conflict between what you knew was right and what you actually did. This honesty is what makes the writing “rich and deep.”

Finally, be careful with your Passive Voice. In reflective writing, passive voice can sometimes sound like you are dodging responsibility.

- Passive: “Mistakes were made in how I treated him.” (Who made them? The empathy fairy?)

- Active: “I made a mistake in how I treated him.”

However, you can use passive voice effectively to describe the feeling of being overwhelmed or controlled by emotion. - Effective Passive: “I was blinded by my own ambition.” (Here, ambition is the actor, rendering you the victim of your own flaw—a nice stylistic touch).

Tips for the Challenge:

- Start in Media Res: Don’t give a long introduction. Drop us right into the moment of the empathy failure. “The coffee was cold, and so was my stare.”

- The Pivot: Halfway through, you need a realization point. What changed your perspective? Was it hours later? Years later? This transition often requires time markers: “It wasn’t until years later that I realized…”

- The Takeaway: End with what this failure taught you about the “survival skill” of empathy. Connect your small story to the bigger picture.

By using the Third Conditional to explore what could have been, Modals of Deduction to analyze the other person, and active verbs to own your actions, you will create a piece of writing that is not just a confession, but a compelling study of human nature.

Grammar and Writing Quiz

Critical Analysis

Look, the article paints a compelling picture. Empathy is the glue, the survival skill, the magic sauce. But if I put on my skeptic’s hat—or my “expert analysis” monocle—I have to point out that we might be romanticizing the concept a bit too much.

First off, we glossed over the Empathy Trap. There is a very real danger in over-identifying with others. When you have high emotional empathy without strong boundaries, you don’t just understand someone’s pain; you drown in it. This isn’t just “fatigue”; it’s enmeshment. It makes you ineffective. A surgeon cannot burst into tears when they make an incision. A lawyer cannot fall apart because their client is sad. We need to talk more about “Professional Detachment” as a form of empathy—caring enough to do your job well, but detached enough to keep your hand steady. The article hinted at this, but it’s a crucial distinction.

Secondly, we focused heavily on the individual’s responsibility to be more empathetic. “You need to listen better,” “You need to be curious.” That’s all true. But what about the structural design that kills empathy? We mentioned algorithms, sure. But look at our urban planning. We build suburbs where we never see our neighbors. We build cars with tinted windows. We build economic systems that pit workers against each other. Asking individuals to “be more empathetic” in a system designed for isolation is like asking someone to swim upstream in a river of concrete. We missed the systemic critique. Maybe we don’t just need better listening skills; maybe we need better cities and workplaces that force interaction.

Also, let’s challenge the idea that “understanding” always leads to “peace.” Sometimes, understanding someone’s point of view makes you realize that your values are fundamentally incompatible. You can have perfect cognitive empathy for a dictator and realize that they genuinely believe they are doing the right thing—and that realization doesn’t solve the conflict; it clarifies that the conflict is inevitable. Empathy isn’t always the bridge to peace; sometimes it’s just the reconnaissance for the necessary battle.

Finally, there’s the labor of empathy. Who is usually expected to do the empathizing? Historically, it’s marginalized groups who have to empathize with the dominant group to survive. Women are often expected to do the emotional labor of “understanding” men. Employees have to “read” their bosses. We need to ask: Is the empathy deficit distributed equally? or are some people doing all the empathizing while others just take?

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions designed to provoke deep thought and debate. These aren’t just “comprehension” questions; they are meant to challenge the premises of the article and your own worldview.

1. Is “Compassion Fatigue” a valid excuse for checking out, or is it a privilege?

We talk about protecting our mental health by tuning out the news. But who gets to tune out? Usually, those who aren’t directly affected by the crisis. Is managing your empathy budget an act of self-care, or is it an act of abandonment toward those who don’t have the luxury of turning off their reality? Where is the line between self-preservation and negligence?

2. Can true empathy exist without shared experience?

The article suggests we can simulate another’s state. But can a billionaire truly empathize with someone living in poverty? Can a man truly empathize with the fear of walking alone at night that many women feel? Or is “cognitive empathy” just an intellectual approximation that will always fall short? Does it matter if it falls short, as long as the effort is made?

3. Is empathy actually biased and dangerous?

Some psychologists (like Paul Bloom) argue that empathy is a spotlight that focuses on one person (usually someone who looks like us) at the expense of the many. We might donate to one cute kid in a viral video while ignoring a famine affecting millions. Does relying on empathy actually distort our moral compass and lead to unfair outcomes? Should we rely on cold, hard rationalism instead?

4. If empathy is a survival skill, why does evolution seem to be rewarding narcissism right now?

The article claims empathy is for survival. Yet, look at the most successful people in modern society—CEOs, influencers, politicians. Many display traits of narcissism and low empathy. If the “system” rewards ruthlessness, is empathy actually a disadvantage in the modern “survival of the fittest”? Are we evolving away from empathy?

5. Should we empathize with “monsters”?

This is the hardest one. When someone commits a heinous act, society demands punishment, not understanding. Is attempting to understand the perpetrator an insult to the victim? Or is understanding the only way to prevent future monsters? Is there a limit to who deserves our cognitive empathy?

0 Comments