There is a distinct, almost masochistic pleasure in reading about the bitter cold while one is comfortably warm. It is a specific genre of satisfaction—curling up under a weighted blanket, a mug of something steaming in hand, and opening a book where the characters are actively freezing to death. We watch them trudge through snowdrifts, their eyelashes frosting over, their fingers turning blue, and we subconsciously snuggle deeper into our cushions. It feels like getting away with something. But beyond the creature comforts of the reader, the season of winter has served as one of literature’s most potent, enduring, and versatile symbols. It is rarely just a backdrop; it is a character, a catalyst, and a philosophy.

Winter in literature is the great clarifier. Summer is messy; it is teeming with life, insects, sweat, and distraction. But winter strips the world down to its bones. It kills off the superfluous and leaves only the essential structure of the landscape—and the essential nature of the characters. When the snow falls, it covers the world in a blank page, inviting the author to write something new, or to reveal what was hidden beneath the noise of the rest of the year.

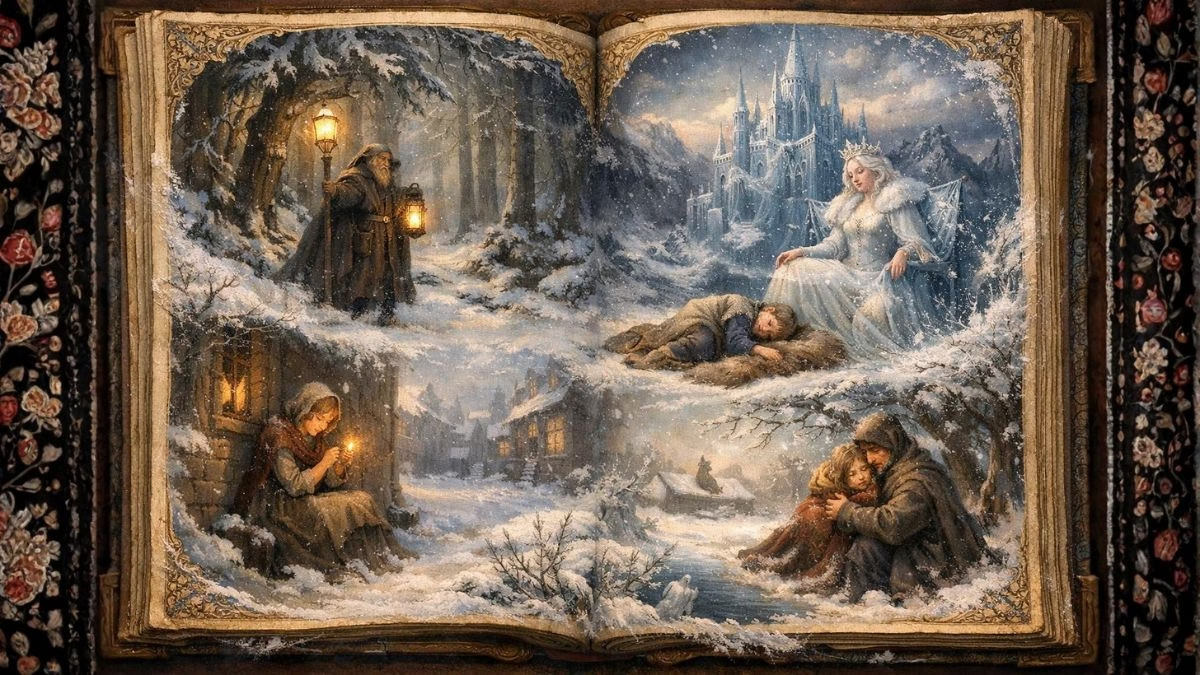

We are going to take a walk through some of the snowiest pages in the canon. We are going to look at how Dickens used the fog to talk about the soul, how C.S. Lewis used ice to talk about politics and theology, and how Hans Christian Andersen used the cold to break our hearts. We will explore the paradox that the warmth of the hearth—that symbol of safety and community—is entirely meaningless without the threat of the storm outside.

Dickens and the Moral Temperature

You cannot talk about winter in literature without bowing at the altar of Charles Dickens. The man essentially invented our modern, secular conception of the “Christmas spirit,” but he did it by dragging us through the slush first. In A Christmas Carol, the weather is not merely atmospheric; it is a manifestation of Ebenezer Scrooge’s internal state.

Dickens writes, “The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shriveled his cheek, stiffened his gait… No wind that blew was bitterer than he.”

Here, the external winter is irrelevant compared to the internal permafrost. Scrooge carries his own low temperature with him; he creates a microclimate of misery. But Dickens also uses the external winter—the London fog, the biting wind—as a social critique. The cold is the great equalizer of the poor. It does not care if you are virtuous; if you have no coal, you will freeze.

The brilliance of Dickens is his use of light against this backdrop. The scenes of the Cratchit family or Fezziwig’s party are not just happy scenes; they are defying the elements. The warmth of their gatherings feels earned because we know exactly how cold it is outside the door. The “hearth” in Dickens is a fortress against a hostile universe. It suggests that human connection is a form of combustion—we generate heat by rubbing our lives against one another. Without the freezing London streets, the Cratchit’s meager goose and small fire would just be poverty. Set against the winter, they become a triumph of the spirit.

Narnia and the Politics of Ice

If Dickens used winter to talk about the heart, C.S. Lewis used it to talk about the state. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the White Witch’s curse on Narnia is arguably one of the most terrifying concepts in children’s literature: “Always winter but never Christmas.”

This is not just a meteorological problem; it is a theological and political nightmare. Winter, in the natural cycle, is a time of rest and death that precedes rebirth. It is a pause. But a winter that never ends? That is stagnation. That is a tyranny of preservation. The White Witch wants a world that is frozen in place, obedient, static, and unchanging.

Lewis understands that the beauty of winter lies in its impermanence. We can admire the snow because we know the crocuses are coming. Remove the hope of spring, and winter becomes a prison. The “thaw” in Narnia is not just ice melting; it is the noise of life returning. It is messy, dripping, and loud. It represents the return of agency and chaos, which totalitarian regimes (represented by the Witch) despise. Lewis teaches us that the cold is only beautiful if it is temporary. Eternal ice is just a tomb.

Andersen and the Indifference of Nature

If we want to strip away the cozy feelings and look at the brutal reality of winter, we must turn to the Danes. Hans Christian Andersen did not view winter with the jolly nostalgia of Dickens. In The Little Match Girl, winter is an executioner.

This story is a masterclass in the contrast between the “illuminated” inside and the desolate outside. The little girl strikes her matches, and in their fleeting light, she sees visions of warmth, food, and love. The flame is the symbol of life and hope, but it is agonizingly small against the vast, freezing night.

Andersen forces the reader to confront the fact that nature is entirely indifferent to human suffering. The snow falls on the just and the unjust alike. But he also introduces the “splinter of ice.” In The Snow Queen, the young boy Kay gets a splinter of a cursed mirror in his eye and his heart. His heart turns to a lump of ice. He ceases to see beauty in organic, messy things (like roses) and only finds beauty in the mathematical perfection of snowflakes.

This is a profound psychological observation. Depression, cynicism, and isolation often feel like a “wintering” of the soul. The cold makes Kay numb. He stops feeling pain, but he also stops feeling love. Andersen posits that pain—the “heat” of emotion—is better than the painless perfection of the ice. To be warm is to be vulnerable; to be frozen is to be safe, but dead.

The Modern Winter: Isolation and Clarity

Moving into more modern territory, literature has often used winter to explore isolation. Think of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining. The snow there is a wall. It cuts the characters off from civilization, forcing them to confront the demons (literal and figurative) trapped inside with them.

Or consider Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton. The winter in Starkfield, Massachusetts, is a physical weight. It presses down on the characters, narrowing their lives, limiting their options, and preserving their misery like a fly in amber. Wharton uses winter to describe a poverty of the spirit, a life stripped of possibility.

But there is a flip side. Writers like Katherine May (in her non-fiction work Wintering, which reads like a novel) argue for the necessity of the fallow period. We live in a society that demands eternal summer—constant productivity, constant growth, constant happiness. Literature reminds us that this is unnatural. Trees do not bloom all year. Bears do not hunt all year.

Winter in literature grants us permission to retreat. It validates the need for dormancy. It tells us that it is okay to close the curtains, light a candle, and just exist for a while. It reframes “doing nothing” as “repairing.”

The Necessity of Contrast

Ultimately, the reason these stories resonate is the principle of contrast. A candle in a sunlit field is invisible. A candle in a pitch-black forest is a beacon of hope.

Literature teaches us that we define things by their opposites. We only understand the concept of “sanctuary” because we understand the concept of “exposure.” The coziness of a Hobbit hole, the camaraderie of the Great Hall in Hogwarts during Christmas, the safety of 221B Baker Street while the London rain lashes the windows—these spaces are defined by what they are keeping out.

This is the lesson of the illuminated page. The light shines brighter when the background is dark. We need the cold winds of literature to remind us why we built the fire in the first place. We need the reminder of the harsh, indifferent universe to understand why human kindness is such a miraculous rebellion.

So, as you read this, perhaps you are warm. Perhaps you are safe. Do not take it for granted. The literature of winter is a ghost story that whispers: It is cold out there. Keep the fire burning.

Focus on Language

Let’s step into the mechanics of the text we just read. When we discuss literature, especially atmospheric literature like winter tales, we have to use words that carry weight. We aren’t just describing temperature; we are describing mood, emotion, and philosophy.

We started by using the word masochistic. This is a strong word. Technically, it refers to deriving sexual gratification from one’s own pain, but in everyday, conversational English, we use it to describe doing something we know will be unpleasant or difficult, yet enjoying it anyway. Reading about freezing people while you are warm is a “masochistic pleasure.” You might say, “I’m going for a run in this freezing rain; I’m feeling a bit masochistic today.” It implies a voluntary hardship.

Then we talked about winter being a catalyst. In chemistry, a catalyst is something that speeds up a reaction without being consumed by it. In storytelling (and real life), a catalyst is an event or person that causes a change. Winter is a catalyst because it forces characters to act. It forces Scrooge to confront his loneliness; it forces the Pevensie children to fight the Witch. You can use this at work: “The new manager was a catalyst for changing the company culture.”

We used the word superfluous. This means unnecessary, especially through being more than enough. We said winter kills off the superfluous. It strips the leaves off the trees; it hides the garden furniture. It removes the clutter. If you are editing an email, you might say, “I deleted the second paragraph because it felt superfluous.” It’s a sophisticated way of saying “extra” or “needed.”

We described the Narnian winter as stagnation. This is a fantastic word. It comes from “stagnant,” like a pond of water that doesn’t flow and starts to smell. Stagnation is a state of not moving, not growing, and not developing. A winter that never ends is stagnation. A career can be in stagnation. An economy can be in stagnation. It is the opposite of flow and growth.

We mentioned the impermanence of winter. This is the quality of not lasting forever. The beauty of snow is its impermanence; it will melt. We often suffer because we forget the impermanence of our problems. Using this word adds a philosophical touch to your speech. “The impermanence of this difficult project is the only thing keeping me going.”

We talked about the indifferent nature of the cold. To be indifferent is to have no particular interest or sympathy; unconcerned. We often think the universe is against us, but literature teaches us the universe is usually just indifferent. The snow doesn’t hate the Match Girl; it just is. If someone doesn’t care about your opinion, they are indifferent to it.

We used the term manifestation. This is an event, action, or object that clearly shows or embodies something abstract or theoretical. We said the weather was a manifestation of Scrooge’s soul. His internal coldness became real, visible weather. If you are stressed, a headache might be a physical manifestation of that stress.

We discussed camaraderie. This is mutual trust and friendship among people who spend a lot of time together. We see this in the feasts in Harry Potter or the Cratchit family dinner. It’s a specific kind of friendship born from shared experience. Soldiers have camaraderie; teammates have camaraderie.

We used the word dormancy. This relates to “dormant,” which means having normal physical functions suspended or slowed down for a period of time; in or as if in a deep sleep. Plants go into dormancy in winter. We argued that humans need dormancy too—a rest period. You can say, “My hobby of painting has been in dormancy for a few years, but I’m picking it up again.”

Finally, we talked about rebellion. We usually think of this as fighting the government, but we used it poetically: “human kindness is a miraculous rebellion.” In a cold, cruel world, being kind is an act of defying the status quo. It’s a soft rebellion.

Now, let’s move to the speaking section.

The vocabulary of winter is often about sensory juxtaposition. That’s a fancy way of saying we place two opposite things next to each other to make them both stand out. Hot and cold. Dark and light. Quiet and loud.

When you are telling a story or describing a scene, if you want to sound advanced, don’t just describe the thing itself. Describe it by what it is not.

Instead of saying: “It was very cold outside, but my house was warm.”

Try using the contrast: “The wind was howling against the glass, which made the silence of the living room feel even deeper.”

See what happened there? We used the sound of the wind to emphasize the silence of the room. We used the violence of the outside to emphasize the peace of the inside.

Here is your challenge. I want you to look out your window (or imagine a scene). I want you to describe the temperature without using the words “hot,” “cold,” “warm,” “freezing,” or “degrees.”

You have to use the environment.

Bad example: “It is freezing today.”

Good example: “The puddles on the sidewalk have turned into jagged mirrors, and I can see my own breath hanging in the air like smoke.”

Try to write or record three sentences describing the weather right now using only environmental clues and juxtaposition. If it’s hot, describe the shimmering air or the seeking of shade. If it’s cold, describe the stiffness of your fingers or the steam from a cup. This forces you to use “visceral” language—language felt in the body.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to spark some deep thinking. I want you to take these not just as questions to answer, but as starting points for a debate with yourself or others in the comments.

1. Is the romanticization of winter a privilege of the wealthy?

We love reading about snow when we have central heating. For the homeless or those in energy poverty, winter is a threat, not an aesthetic. Does literature that beautifies the cold ignore the reality of suffering? Is the concept of “cozy” (hygge) inherently classist?

2. If Narnia’s “always winter” is a dystopia, is a world of “always summer” a utopia?

Think about the genre of “Solarpunk” or tropical paradises. If we never had winter, would we become culturally or spiritually “stagnant” in a different way? Does constant ease and warmth lead to laziness or a lack of character development, as some Victorian philosophers believed?

3. Does suffering actually ennoble us, or is that just a story we tell ourselves?

Dickens suggests that the Cratchits are noble because they struggle against the cold and poverty. Andersen suggests the cold just kills you. Is the idea that “hardship builds character” a toxic myth we use to justify not helping people, or is there truth to the idea that the “cold” makes us better people?

4. Why is the genre of Horror so frequently set in snow?

Think of The Shining, The Thing, Misery. What is it about snow that scares us? Is it the isolation? The silence? The fact that snow hides things? Or is it the “white page” effect—that anything can happen on it?

5. Has the “digital hearth” replaced the physical one?

We talked about the hearth (fireplace) as the center of the home and storytelling. Today, we gather around glowing screens. Does the “blue light” of a phone serve the same social function as the fire, or does it isolate us? Are we “freezing” socially because we no longer huddle together for warmth?

Critical Analysis

We have spent a lot of time praising the literary use of winter, but let’s take a step back and look at the blind spots in this analysis. We are looking at this through a very specific, very Western lens.

The article focuses heavily on the “Northern” experience—Dickens (UK), Andersen (Denmark), Lewis (UK/Ireland). In these cultures, winter is the death of the year. But what about literature from the equator? What about the Southern Hemisphere? In Australian literature, “Christmas” is scorching heat and bushfires. In Indian literature, the monsoon might be the “great clarifier” rather than the snow. By defining “winter” as this universal symbol of death and reflection, we are excluding a massive part of the human experience where heat is the deadly force and the “cold” is actually the relief.

Furthermore, we need to be careful about the “Contrast Theory”—the idea that we need pain (cold) to appreciate joy (warmth). This is a very convenient philosophy. It borders on justifying suffering. It suggests that the Little Match Girl had to die so that we could appreciate our fireplaces. That is a morally dangerous path. Do we really need the threat of death to appreciate life? Can’t we just appreciate a warm meal without someone else freezing outside? Literature often romanticizes this duality, but in reality, misery is often just misery, not a poetic teaching moment.

Lastly, there is a heavy dose of nostalgia in our appreciation of these stories. We read Dickens and think of chestnuts roasting, but we forget the tuberculosis, the soot-choked air, and the child labor that powered those “cozy” Victorian winters. We are sanitizing the past. We are enjoying the aesthetic of the “hearth” while forgetting that the hearth was the only source of heat and if it went out, you died. Our modern reading is a luxury product, detached from the visceral reality the authors were actually describing.

0 Comments