- Audio Article

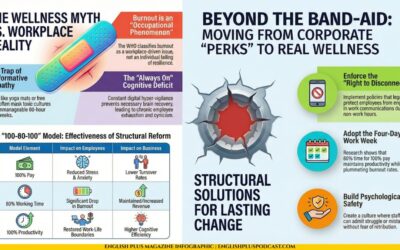

- The Tyranny of the Present: Scarcity and the Tunnel-Vision Mind

- The Brain Under Siege: Chronic Stress and Its Neurological Fallout

- The Science Behind “Bad Decisions”

- Breaking the Cycle: Designing for Bandwidth

- A New Conversation About Poverty

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Let’s Think Critically

- Let’s Play & Learn

Audio Article

We have a deep-seated, almost mythical belief about escaping poverty. It’s the story of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” The narrative is simple: with enough grit, hard work, and a string of good decisions, anyone can climb the ladder of success. It’s a powerful and appealing story. And for some, it’s even true. But it leaves out a crucial, invisible character in the drama of a person’s life: the brain.

We like to think of our decision-making as a pure reflection of our character, our intelligence, our willpower. But what if it isn’t? What if the very organ we use to make those “good decisions” is being fundamentally altered by the environment it’s forced to operate in? What if poverty isn’t just a lack of resources out in the world, but a constant, grinding force that reshapes the neural pathways inside our heads?

This is not a metaphor. A growing body of research from neuroscience, psychology, and economics is revealing a startling truth: the chronic stress and persistent scarcity of poverty impose a staggering cognitive load on the human brain. This isn’t about intelligence or character. It’s about bandwidth. Living in poverty is like running a dozen complex applications on a computer with not enough RAM. The system slows down, freezes, and is forced to make trade-offs just to keep functioning. This hidden burden rewires the brain, impacting everything from memory and focus to long-term planning and impulse control. To ignore this biological reality is to fundamentally misunderstand the poverty trap and to blame people for succumbing to a force that is actively hijacking their cognitive machinery.

The Tyranny of the Present: Scarcity and the Tunnel-Vision Mind

To understand how poverty affects the brain, we first have to understand the psychology of scarcity. Scarcity isn’t just the objective state of not having enough; it’s a mindset that captures our attention and changes how we think. Researchers Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir, in their groundbreaking book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, lay out a powerful argument. They contend that scarcity of any kind—whether it’s a scarcity of money, time, or even food—forces our brain to adopt a specific kind of tunnel vision.

The Focusing Dividend

When you are desperately trying to figure out how to pay rent by Friday, your mind becomes incredibly focused on that problem. You become a brilliant, short-term crisis manager. You can remember the exact due dates of every bill, you know which creditor is the most aggressive, and you can perform complex mental calculations about which needs can be put off for another week. This is what Mullainathan and Shafir call the “focusing dividend.” Scarcity makes you a temporary expert at juggling the immediate threats.

This is a powerful survival mechanism. When a lion is chasing you on the savanna, you don’t have time to contemplate your five-year plan. Your brain funnels all its resources into one thing: don’t get eaten. The problem is that modern poverty isn’t a lion that you can escape from in a few minutes. It’s a lion that lives in your house. The state of acute crisis is not temporary; it is chronic.

The Bandwidth Tax

While you are hyper-focused on the immediate crisis, what happens to everything else? This is where the “bandwidth tax” comes in. Cognitive bandwidth refers to our capacity for all the high-level thinking that makes us effective humans: our executive function (which we’ll get to), our self-control, our long-term planning, our fluid intelligence. Scarcity eats this bandwidth for lunch.

Think about it. While your brain is consumed with the rent-money calculation, you have less mental capacity left over to remember to give your child their medication, to fill out a complicated financial aid form, or to plan a healthy meal for the week. You are more likely to be irritable with your kids, not because you’re a bad parent, but because your brain’s ability to regulate emotion is depleted.

This has been demonstrated in stunning experiments. In one study, shoppers at a New Jersey mall were asked to solve a series of cognitive tests. Before the tests, they were presented with a hypothetical scenario: their car needed a repair. For half the participants, the repair was cheap ($150). For the other half, it was expensive ($1,500). The results were fascinating. For the wealthy shoppers, the cost of the repair made no difference to their performance on the tests. But for the low-income shoppers, simply thinking about the expensive repair caused their scores to plummet by an amount equivalent to losing 13 IQ points. To put that in perspective, that’s the cognitive difference between being a normal adult and a chronic alcoholic, or the drop you’d experience after losing an entire night of sleep. The mere thought of a financial threat was enough to temporarily cripple their cognitive function.

This is the hidden burden. It’s not that people in poverty are less intelligent. It’s that poverty itself is actively, constantly, and relentlessly taxing their intelligence.

The Brain Under Siege: Chronic Stress and Its Neurological Fallout

The mindset of scarcity is intimately linked with another powerful biological force: chronic stress. The human stress response system is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. When faced with a threat, your adrenal glands flood your body with hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. Your heart rate increases, your senses sharpen, and energy is diverted to your muscles. It’s the “fight-or-flight” response, and it’s designed to save your life from short-term dangers.

But what happens when the threat never goes away? The constant worry about food, safety, bills, and housing means the stress-response system is permanently switched on. The cortisol never subsides. This is chronic stress, and it is profoundly toxic to the brain.

The Hijacking of the Prefrontal Cortex

One of the brain regions most vulnerable to the effects of chronic stress is the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC is effectively the CEO of your brain. It’s located right behind your forehead and is responsible for all the sophisticated thinking we call “executive function.” This includes:

- Working Memory: The ability to hold and manipulate information in your head (e.g., remembering a phone number while you dial it).

- Cognitive Flexibility: The ability to switch between tasks and adapt your thinking to new information.

- Inhibitory Control: The ability to resist impulses and temptations in favor of a better long-term outcome (e.g., saying no to an impulse buy).

Chronic exposure to cortisol damages neural connections in the PFC. It literally weakens the CEO. At the same time, it strengthens the connections in the amygdala, the brain’s primitive fear and emotion center. The result is a neurological coup. The emotional, reactive, fear-driven part of the brain gains more control, while the thoughtful, deliberative, long-term planning part gets weaker.

This isn’t a personality flaw; it’s a physiological adaptation to a threatening environment. The brain is rewiring itself for survival in a world that feels permanently dangerous. The problem is that the very adaptations that help you survive the crisis of today are the ones that make it so much harder to plan your way into a better tomorrow.

The Science Behind “Bad Decisions”

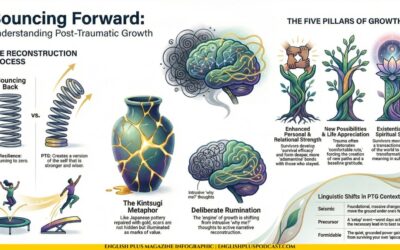

When we understand this cognitive and neurological fallout, many of the behaviors that are often stereotyped as “bad decisions” or “character flaws” of the poor start to look like predictable, even rational, outcomes of a system under siege.

Why Long-Term Planning Is So Hard

Let’s say you’re offered a “payday loan.” It’s a small amount of cash to get you through the week, but with an astronomical interest rate. From a long-term financial perspective, taking this loan is a terrible decision. It will dig you into a deeper hole.

But if your cognitive bandwidth is completely consumed by the immediate crisis of feeding your kids tonight, the “long-term” is a luxury you can’t afford to think about. Your brain, rewired by scarcity and stress, is screaming for a solution now. The weakened PFC struggles to assert the long-term consequences over the amygdala’s demand for immediate relief. Taking the loan isn’t an act of foolishness; it’s a desperate attempt to solve the most pressing problem in the tunnel.

The Logic of Impulse Buys

Similarly, consider the person who receives a small windfall—a tax refund, perhaps—and spends it on something that seems frivolous, like a new TV, instead of paying down debt. From the outside, this looks like poor financial management.

But from the inside, it can be understood through the lens of cognitive depletion. The mental effort required to constantly say “no,” to deny yourself and your family any small pleasure, is immense. This is the concept of decision fatigue. Our capacity for self-control is a finite resource. After a day—or a lifetime—of making high-stakes trade-offs about which necessity to sacrifice, the well of willpower runs dry. The TV isn’t just a TV; it’s a moment of relief, a release from the relentless grind of deprivation. It’s a purchase driven by an exhausted brain seeking a sliver of normalcy and joy in a world defined by “no.”

The Impact on Health and Parenting

This cognitive burden spills into every other area of life. A parent with depleted bandwidth is more likely to be inconsistent with discipline, not because they don’t love their children, but because the mental energy required for patient, consistent parenting has been spent elsewhere. They are less likely to engage in the kind of enriching conversation that builds a child’s vocabulary because their mind is occupied by a thousand other worries.

The effects on health are just as stark. The constant stress contributes to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders. And the cognitive tax makes it harder to manage chronic physical illnesses like diabetes, which require consistent monitoring, planning, and adherence to a strict regimen. Missing a dose of medication isn’t a sign of carelessness; it’s a symptom of a brain that is simply overloaded.

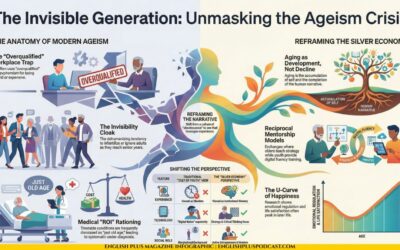

Breaking the Cycle: Designing for Bandwidth

If poverty imposes a massive tax on our mental resources, then what is the solution? The answer isn’t to just tell people to “try harder” or “make better decisions.” That’s like telling the person running from the lion to think more about their retirement savings. The solution is to change the environment. It’s to design systems and policies that actively reduce the cognitive load on people living in poverty.

This is a paradigm shift in how we think about aid and social programs. Instead of just providing resources, we need to think about how to provide them in a way that is simple, predictable, and frees up mental bandwidth.

For example, traditional welfare programs are often a nightmare of complexity. They require mountains of paperwork, frequent recertification appointments, and confusing eligibility rules. This complexity imposes a huge bandwidth tax on the very people the programs are meant to help. A redesigned system would be streamlined and automated. Forms would be simpler. Eligibility would be easier to maintain. The goal would be to make accessing help as cognitively easy as possible.

Predictability is another key. A worker in the gig economy whose income fluctuates wildly from week to week is living under a constant cognitive burden of uncertainty. Policies that create more stable and predictable incomes—like a higher minimum wage or a form of basic income—don’t just provide more money; they provide more peace of mind. They free up the mental space that was once consumed by the frantic weekly scramble, allowing it to be used for planning, learning, and parenting.

Even small interventions can have a big impact. One experiment sent simple text message reminders to parents to encourage them to read to their children. This simple nudge helped cut through the cognitive clutter and led to significant gains in the children’s literacy skills. The intervention didn’t teach the parents anything new; it simply helped them execute on an intention they already had by making it easier to remember in a moment of mental overload.

A New Conversation About Poverty

Understanding the neuroscience of poverty is not about making excuses. It’s about providing a more accurate explanation. It’s about replacing the damaging and scientifically baseless myths of character flaws with a modern understanding of how the brain responds to its environment.

It forces us to ask a different set of questions. Instead of asking, “Why do they make such bad decisions?” we should be asking, “What is it about their environment that is draining their cognitive resources and making good decisions so incredibly hard?” Instead of blaming individuals for a lack of willpower, we should be examining the systems that deplete that willpower day after day.

This hidden burden is perhaps the cruelest aspect of the poverty trap. It not only robs people of their resources, but also of the very cognitive tools they need to escape. It makes the climb out of the hole not just a physical struggle, but a profound mental one. Recognizing this doesn’t absolve anyone of personal responsibility, but it does demand a new level of empathy, humility, and, most importantly, a smarter, more compassionate design for our social policies. The first step in helping someone carry a heavy load is to see just how much it truly weighs.

MagTalk Discussion

MagTalk Discussion Transcript

Is making a truly critical decision, say, choosing between paying down debt or fixing a leaky roof, is that purely a matter of willpower, you know, person character? Or is something far deeper, maybe something biological, actively undermining that whole decision-making process? What if we told you that the simple grinding act of just worrying about money could temporarily drop your measurable IQ score by the equivalent of pulling a 24-hour sleepless shift? We’re diving into the staggering, yet often hidden, burden of scarcity and chronic stress. We’re exploring how poverty doesn’t just limit external resources like cash or housing. It actively, physiologically hijacks the very organ we rely on to plan for a better future, the brain itself.

This is really about the biological poverty trap. Yeah, usually when we talk about poverty, we quantify it in dollars, maybe euros, pounds, whatever, dollars and cents. But today we’re looking at it in terms of cognitive capacity, in neural connections, in sheer mental bandwidth.

And that completely shifts the focus, doesn’t it, from some kind of moral failing to, well, a biological tax. Welcome to a new MagTalk from English Plus podcast. Okay, so we’re jumping right into a conversation that, honestly, it fundamentally challenges one of the most ingrained narratives we have.

You know the one, the bootstraps idea. The pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstrap story. Exactly.

It’s a compelling story, powerful even. Suggests that escaping poverty is all down to individual grit, unwavering effort, and crucially making just a relentless string of undeniably good rational decisions. It is a satisfying narrative.

Yeah. Because it provides clear accountability, right? Yeah. If you succeed, well, it proves your worthiness, your intelligence, your willpower.

And if you fail… Then the blame falls on you. The system says, well, you must have lacked grit, must have made bad decisions. It puts the burden entirely on the individual’s internal machinery, you know.

Yeah. Their choices. But the core question our material today raises is, what if that machinery, that engine of willpower and strategic choice, what if it’s running on fumes because the environment has fundamentally altered it? We really need to introduce this missing character in the whole social mobility drama, the brain under siege.

Precisely. We have to confront the reality that poverty isn’t just an external condition, a lack of cash or stable housing. It’s a constant grinding internal force.

And it actively reshapes our neural pathways, our cognitive capacity. Yeah. This isn’t just theory.

This is, it’s measurable. Okay. So this brings us to these core concepts.

They’re coming out of behavioral economics, neuroscience, cognitive load and bandwidth. Can you walk us through that framework? Because it really feels like the key here. Right.

Think of your mind, your capacity for complex thought, memory, planning, self-control. Think of it like a computer system. Okay.

It has a finite amount of processing power, RAM, you know. Yeah. The short-term memory it uses to run programs.

And what the research calls bandwidth is basically that finite capacity for high level thinking. Got it. And when someone’s living in chronic financial stress, that computer isn’t just running simple stuff like checking email.

Oh, definitely not. It’s simultaneously running incredibly complex high resource software. Like calculating weekly transport costs for maybe three different part-time jobs.

Yeah. Navigating really complicated government aid forms, juggling calls from aggressive creditors, worrying about where dinner for the kids is coming from tonight. That system, no matter how good the basic hardware is, it just slows down.

It freezes up sometimes. It’s forced to ruthlessly prioritize only the immediate survival functions. And that constant drain, that unavoidable depletion of mental resources, that’s the cognitive tax we’re talking about.

That’s exactly it. The cognitive tax. So the real mission of this deep dive then is to move past that simplistic moral judgment.

We need to understand this biological reality so we can stop blaming people for succumbing to these environmental forces that are quite literally hijacking the sophisticated cognitive machinery they need to plan for a better tomorrow. It’s a necessary shift, really. If the actual capacity for good decision-making is depleted by scarcity itself, well then the solution can’t just be try harder.

Right. It must involve alleviating the scarcity, reducing that cognitive load. Okay, let’s dive into part one then.

The tyranny of the present. Scarcity and this bandwidth tax. Let’s start with the immediate psychological environment.

What researchers call the psychology of scarcity. And you mentioned this isn’t just lacking money. Right.

That’s the crucial distinction. Scarcity isn’t just the objective state of lacking something, money, time, food, whatever. It’s a specific mindset that it imposes on you.

A mindset. How so? Well, scarcity acts like a psychological magnet. It captures and redirects all your available attention.

It funnels it relentlessly toward the immediate pressing lack. So the constant awareness of that deficit, it just dominates your mental landscape. But ironically, there’s a short-term benefit to this focus, right? The focusing dividend.

Yes, that’s the interesting part. The brain is fundamentally an efficiency engine, always prioritizing survival. So when you’re faced with an immediate threat, like say an unexpected car repair bill, that means you might lose your job if you can’t get to work.

Okay. Your cognitive machinery becomes hyper-focused on solving that immediate problem. All available resources are marshaled right there.

So you temporarily become a genius at triage. You know exactly when the electric bill is due, the penalties, which creditor you can maybe ignore for another day or two. And you’re doing complex mental math about trade-offs.

If I pay the gas bill now, can I push the grocery shopping to Friday? That kind of thing. Exactly that. It’s highly effective acute crisis management.

And there’s a deep evolutionary route to this. Think about early humans. If you’re being chased by a lion, your brain instantly funneled every calorie, every neuron into the don’t-get-eaten protocol.

You wouldn’t stop to think about your long-term retirement plan. Makes sense. But that’s where the analogy breaks down with modern poverty, doesn’t it? The lion, eventually, it either catches you or it goes away.

Or you escape. But in chronic scarcity, the lion never leaves. That state of acute life-or-death crisis becomes permanent.

And if your brain is constantly running this don’t-get-eaten survival software, you never have the mental luxury, the bandwidth, to divert cognitive resources to the long-term strategic planning that requires a calmer, more reflective state of mind. And this constant mental deployment, running that survival software all the time, leads directly to the bandwidth tax. We know bandwidth is that capacity for high-level thinking, executive function, planning, fluid intelligence.

How exactly does scarcity consume this bandwidth for everything else? Well, it’s basically a zero-sum game, isn’t it? The processing power being used to stress about how to make, say, $100 appear by Tuesday morning. That’s processing power that’s not available for other complex tasks. And these are often vital non-financial tasks that get pushed aside simply because they don’t feel like an immediate survival threat.

Can you give some concrete examples what kind of tasks suffer? Oh, it could be something seemingly small, like failing to remember a child’s complex medication schedule or forgetting an important dentist appointment. It could be the inability to focus deeply enough to accurately fill out, you know, a 10-page financial aid form. Or a housing assistance application, which often means the application gets rejected and the whole stressful cycle starts over again.

Wow. Or even just the cognitive effort required to plan three days’ worth of genuinely healthy, affordable meals. These aren’t huge moral failings.

They’re small cognitive failures that accumulate rapidly under load. And this depletion, it spills over into emotional regulation too, right? Like the irritability or short temper we sometimes associate with high-stress situations. It’s not necessarily a character flaw.

Absolutely not. It’s fundamentally a resource depletion issue. Managing your emotions, exercising patience, resisting the urge to snap.

These are all functions heavily reliant on the prefrontal cortex, which we’ll talk more about. When your cognitive battery is flashing red at 1%, the ability to perform that high-cost task of self-control is just gone. The person isn’t inherently unkind.

They’re mentally exhausted. They’ve already spent all their regulatory energy managing the financial crisis. This connection between financial pressure and actual measurable intelligence, that’s what takes this from interesting theory to something really profound socially.

Let’s really dig into that New Jersey mall study. Because it seems to perfectly isolate the effect of just thinking about scarcity. Yes.

It was a truly brilliant piece of behavioral research. The setup involved two main groups of shoppers in a mall. Those identified as relatively wealthy, high-income, and those identified as low-income.

Both groups were asked to perform standard cognitive tests. These tests measure core mental abilities like fluid intelligence and executive function, basically. Problem solving and mental control.

But the key manipulation, the twist, happened right before they took the test. Exactly. Before the cognitive test, the researchers presented both groups with a hypothetical scenario.

They were asked to think about their car needing a repair, and then they varied the cost of this hypothetical repair. Okay, so half the shoppers got a minor financial threat. Yes.

A relatively low-cost repair. Maybe $150. Something inconvenient, but not catastrophic for most.

But for the other half, the cost was significant. A major high-stakes financial threat. Like $1,500.

And the critical point here is they just had to think about it. No actual money changed hands. They were just priming them with a financial worry.

So what happened with the wealthy shoppers? Did thinking about the big $1,500 repair hit their scores? Almost not at all. For the high-income group, the hypothetical cost, whether it was $150 or $1,500, made virtually no measurable difference in their cognitive performance on the tests that followed. For them, you know, $1,500 might be annoying, but it wasn’t a bandwidth-consuming crisis.

It was just background noise. Okay, but for the low-income shoppers, who were already living under real financial strain day-to-day, the result was starkly different, just based on which number they were shown. Profoundly different.

When the low-income group was prompted to think about the minor $150 repair, their scores were relatively high. They performed pretty well, reflecting their baseline intelligence. But when they were simply prompted to think about the expensive $1,500 repair, their cognitive test scores plummeted.

Dramatically. And we really need to stress the size of that drop. This isn’t some subtle effect, right? It’s a huge shift in mental capacity.

The decline was quantified as being equivalent to losing around 13 IQ points. 13 points. Yeah.

And to really grasp the magnitude of that, that kind of cognitive deficit, is comparable to the impairment you see after pulling an all-nighter, going entirely without sleep. Or it’s similar to the level of cognitive decline observed in individuals suffering from chronic alcoholism. It’s the difference between functioning at a highly capable level and functioning under a severe acute impairment.

So poverty isn’t just about lacking money. The worry itself, the cognitive load imposed by just managing scarcity, it temporarily reduces your effective intellectual capacity by an amount equivalent to a major physiological stressor like sleep deprivation. That’s the core takeaway here, isn’t it? That is the biological reality.

Yeah. It’s not that people experiencing poverty are inherently less intelligent. It’s that the state of poverty is actively, constantly, and relentlessly taxing that intelligence.

It’s consuming the very bandwidth they need to make the strategic long-term decisions that could potentially help them escape. And this leads to that idea of cognitive tunneling, right? If all your mental energy is focused laser-like on the immediate crisis-like, the light at the end of the tunnel is just this week’s rent payment. You lose the peripheral vision needed to see other opportunities, or maybe dangers, lying just outside that immediate path.

Exactly. The tunnel vision is, in a way, a survival mechanism. It creates hyper-efficiency for dealing with the immediate threat.

But while you’re solely focused on those critical few tasks inside the tunnel, you become effectively blind to essential secondary tasks. Things like preventative health care, maybe signing up for a job training program that could pay off later. They just don’t register.

They don’t register because all cognitive resources are allocated elsewhere. And that’s the cruel irony, isn’t it? The very adaptations that help you survive today actively impair your ability to plan and thrive tomorrow. Okay, so that covers the functional costs, the bandwidth tax.

Let’s move into part two, the brain under siege. The actual physiological mechanism. If the scarcity mindset is the psychological strain, then the biological result is chronic stress.

And that stress, as the research shows, is basically toxic to the brain over time. That’s right. The brain’s stress response system, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis or HPA axis, it’s designed for short-term acute threats.

You know, the classic fight or flight response. It floods the body with adrenaline and cortisol stress hormones. Your heart rate goes up.

Energy is diverted from digestion to your muscles. Your brain prioritizes immediate danger assessment. All good things if a lion is actually chasing you.

Absolutely. Yeah. It saves your life from that immediate short-term danger.

But in the context of persistent modern scarcity, that threat never really gets resolved, does it? The landlord is always potentially looming. The gas tank is always near empty. The bills just keep coming.

Exactly. The system gets stuck in the on position. And cortisol, which is incredibly useful for short bursts of stress, becomes toxic when it’s chronically elevated.

These high persistent levels of stress hormones begin to fundamentally alter the physical structure of the brain. They don’t just deplete your temporary bandwidth. They actually start to degrade the hardware itself.

And the region that seems to take the biggest hit, the most significant measurable damage, is the brain strategic command center. The CEO, as you called it earlier, the prefrontal cortex, the PFC. That’s right.

The PFC is the area right behind your forehead. It’s the seat of all our sophisticated executive functions. It’s what allows us humans to think abstractly, plan for the future, make complex decisions, and override our basic instincts.

And chronic cortisol exposure damages this critical region in, well, at least three crucial ways affecting its core functions. OK, let’s break down those three core functions of the PFC that get degraded, starting with working memory. Right.

Working memory is essentially your mental scratch pad. It’s the capacity to hold and actively manipulate information in your head right now. Think of it like a juggler.

If you’re trying to juggle three important items, maybe a phone number you just heard, a short grocery list, and your child’s school schedule, and then someone throws a new, complex instruction at you. If your working memory is already impaired or overloaded, you’re likely to drop everything. For someone constantly dealing with scarcity, that working memory is already dedicated to high-stakes calculations.

What’s the absolute maximum I can spend on lunch today if I need enough left for the bus ticket home tomorrow? That constant high-stakes mental math just exhausts the system. And if your working memory is hijacked like that, even simple daily tasks must become a monumental effort, like following complex instructions at a new job, or maybe completing a multi-step chore at home. Exactly.

It makes everything harder. The next key function that suffers is cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility.

What exactly is that? It’s the ability to adapt your thinking, to pivot, to switch between different thought processes or tasks when the situation changes or demands it. Why is that flexibility so important, and how does chronic stress mess with it? Well, flexibility is absolutely essential for effective problem solving. If plan A suddenly fails, can you quickly generate a plan B, and maybe even a plan C? Chronic stress tends to make our thinking more rigid, more reactive.

If the PFC is damaged or overloaded, the ability to shift perspective, maybe adapt to a sudden change in welfare policy rules, or even learn a new, more efficient way of doing something. That ability is severely curtailed. People tend to stick to the immediate familiar path, even if it’s inefficient, because the cognitive energy required to innovate or adapt feels just too high.

Okay, and the final core PFC function, the one that maybe gets the most public judgment, is inhibitory control. Basically, self-control. Yes, and this is really the linchpin for any kind of strategic long-term behavior.

Inhibitory control is what allows you to resist that immediate, tempting impulse. Like the quick, easy purchase, the angry outburst, the incredibly high-interest loan in favor of a better, larger reward that’s further down the road. And here’s the really stark biological finding.

Chronic cortisol literally causes something called dendritic retraction in the prefrontal cortex. Dendritic retraction, what does that mean in plain terms? It means the connections, the little branches between neurons that allow the CEO of the PFC to communicate effectively, to weigh options, make complex plans. Those connections are literally shrinking, they’re weakening.

So the PFC’s ability to exert top-down control is physiologically reduced. Wow. And while the CEO, the PFC, is being weakened, something else is happening simultaneously.

That’s right. At the same time, connections are actually being strengthened in the amygdala. The amygdala.

That’s the more primitive part. Yes, it’s the brain’s primitive fear and emotion center. Kind of like the smoke detector.

In an environment that feels dangerous and uncertain, which is exactly what chronic poverty simulates for the brain, it makes perfect, albeit damaging, evolutionary sense for the fear center to become more dominant, more reactive. So the net result is effectively a neurological coup d’etat. You could frame it that way.

The emotional, reactive, fear-driven part of the brain, the amygdala gains control, while the thoughtful, long-term planning part, the PFC, gets weaker. And crucially, this isn’t a conscious choice someone makes. It’s a physiological adaptation designed for survival in what the brain perceives as a state of permanent danger.

And that is the truly insidious nature of the poverty trap, isn’t it? The brain has rewired itself to be brilliant at short-term survival, at managing the crisis of today. But in doing so, it has systematically undermined the very cognitive tools, the self-control, the planning capacity required to make the strategic investments needed to escape the crisis of tomorrow. It creates this vicious, self-reinforcing biological cycle.

The system designed purely to survive is also the system that prevents thriving. Okay, part three. Let’s use this framework now to reinterpret some common behaviors often labeled as bad decisions.

When we look through this neurological lens, depleted bandwidth, hijacked PFC, many decisions that society often judges as foolish or lazy or just poor management, they suddenly start to look predictable, maybe even rational given the constraints of the operating system they’re running on. Exactly. It helps us reframe some really catastrophic financial decisions.

Let’s start with one of the most destructive traps out there, the payday loan. Right. From a purely cold calculating financial viewpoint, taking out a short-term loan with an APR annual percentage rate that can hit 400%, 500%, it’s almost guaranteed long-term economic disaster.

So why would any rational adult make that choice? Because the very concept of long-term is a luxury that scarcity has effectively stolen from their mental landscape. When you are deep inside that cognitive tunnel we talked about, the only reality that truly matters is the immediate, often excruciating pain of the present moment. The primary pain point isn’t the 400% interest rate due a month from now.

The primary pain point is the electricity getting shut off tonight or the child having no dinner tonight. So the brain is just screaming for immediate pain relief and the payday loan offers that instant fix, however costly, later. Precisely.

The weakened PFC, already struggling with depleted inhibitory control, is completely outmatched by the powerful emotional drive coming from the amygdala, demanding immediate security, immediate relief. Taking that loan isn’t usually an act of ignorance about financial math. It’s often a desperate, exhausted attempt to solve the single most pressing problem imaginable right now.

It’s a triage action, accepting future damage in exchange for immediate survival. That framework of exhaustion and seeking immediate relief, it also sheds light on one of the most frequently judged behaviors, the windfall dilemma. This is when someone receives a sudden chunk of money, maybe a tax refund, a small insurance payout, and instead of, you know, diligently paying down debt or building savings, they spend it on something that seems frivolous from the outside, like a big screen TV or a fancy gaming system.

Oh, yes. And the immediate reaction from people outside that scarcity tunnel is often quite harsh judgment, isn’t it? Why are they so terrible at managing money? How irresponsible. But this judgment completely ignored the lifetime cumulative effect of something called decision fatigue.

Decision fatigue. Explain how that impacts this specific moment when a windfall arrives. Remember, self-control is a finite mental resource.

Like a muscle, it gets tired. People living in poverty spend virtually every waking moment engaged in high-stakes trade-off calculations. Which bill absolutely has to be paid this week? Which necessity gets sacrificed? Do I take the slightly more expensive bus route to save 15 minutes of precious sleep? Or do I walk the extra mile? That is a constant mental marathon.

And it is utterly, profoundly exhausting. So when that unexpected windfall arrives, it’s not just about the money itself. It’s also about the temporary, maybe illusory feeling of escaping that constant constraint.

It’s the ultimate mental break. A release valve. The purchase of the TV or the other seemingly frivolous item, it’s often not an act of poor financial planning in that moment.

It’s the action of a brain that has been deprived, exhausted and chronically stressed for so long, seeking just a momentary release from that relentless grind. It’s a desperate grasp for a tiny sliver of normalcy, maybe dignity or just simple joy. It’s a way to finally say yes after a lifetime of cognitive deprivation, forcing you to say no to almost everything.

It provides immediate, tangible emotional relief, which the stress-hijacked brain is practically programmed to crave. And this cognitive burden, this tax, it spills over into areas far beyond just personal finance, right? It deeply impacts the family unit health outcomes. Let’s talk about parenting inconsistency.

Yes, this is vital to understand. A parent who has cognitively overloaded their bandwidth, completely consumed by financial stress, is far more likely to be inconsistent in their discipline. And this isn’t because of a lack of love or devotion to their children.

It’s because the sheer mental energy required for patient, consistent, measured parenting is simply unavailable. It’s already been spent elsewhere. Consistent parenting demands immense executive function, the ability to stay calm under pressure, process the child’s perspective, remember the house rules, enforce them evenly time after time.

So if the parent’s working memory and inhibitory control are already burnt out just managing the daily financial crisis, they default to reacting emotionally rather than providing that measured response. That’s often what happens. They might snap or give in easily or swing between being overly strict and overly lenient because the cognitive resources for consistency just aren’t there.

And the impact on the child’s own cognitive development can be immediate and direct. If a parent’s mind is constantly consumed by external worries, rent, food, safety, they have less mental space available for those enriching spontaneous conversations. You know, the critical back and forth interactions that are so important for building a child’s vocabulary, their understanding of the world, their early cognitive foundations.

The parent might be physically present, but their mental bandwidth is tied up elsewhere, effectively reducing the quality and quantity of that crucial interaction. And finally, let’s touch on health management, especially managing chronic illnesses that must become exponentially harder under this kind of cognitive load. Absolutely.

Consider a complex condition like type 1 diabetes. Managing it effectively requires constant planning, strict adherence to a detailed regimen, careful meal calculation, remembering precise medication schedules and dosages. All of these demands fall squarely under the umbrella of executive function.

Working memory, planning, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, they’re all essential. So missing a crucial dose of insulin or forgetting an important dietary restriction. From the outside, it might look like carelessness or noncompliance.

But it’s really a symptom. It’s often a symptom of an overloaded brain operating on severely taxed working memory and planning abilities. For someone who’s effectively operating with that 13 IQ point cognitive deficit every single day due to scarcity, the sheer logistics of immediate survival, finding food, paying bills, literally take precedence over the complex logistics of long-term health management.

This leads directly to poorer health outcomes across the board for people experiencing poverty. The system in many ways is set up to fail the individual on multiple interconnected levels. OK, so the evidence seems overwhelming.

Poverty imposes this massive, invisible yet measurable cognitive tax. If we accept that, then the solution cannot logically be the old moralistic approach of just telling people to try harder or make better choices. We’re essentially blaming the individual for the depletion of resources that their environment is actively draining from them.

The paradigm shift has to be total. We need to move the focus entirely away from blaming individual character towards redesigning the systems themselves. The solution isn’t trying to fix the person.

It’s to actively redesign the environment to reduce the cognitive load imposed by things like bureaucratic complexity and constant grinding uncertainty. Which is a pretty radical departure from how many social assistance or welfare programs currently function, isn’t it? Sometimes they seem almost designed to impose complexity. They often are, perhaps inadvertently, bureaucratic nightmares.

And they impose a massive bandwidth tax on the very people they are intended to help. Think about all the friction points. Traditional welfare programs often require incredibly frequent recertification, sometimes monthly, involving confusing, multi-page paperwork.

Eligibility rules can be convoluted, hard to understand, and they might change without clear notice. And just accessing these systems often requires resources, time, transport, internet access, a printer that scarcity itself has already limited. Precisely.

If you’re asked to provide, say, three months of detailed bank statements, multiple proofs of address, signed documentation from various sources, and the deadline is next Tuesday, you need significant cognitive bandwidth just to organize that. You need reliable internet, maybe access to a scanner or copier, possibly money for transport to a government office during limited hours. For someone whose effective 13 IQ points are already being consumed by the daily crisis, this process can create an almost insurmountable obstacle.

The result is often what’s called administrative churn. People get kicked off essential programs not because they actually fail to qualify anymore, but simply because they lack the cognitive energy, the bandwidth, to navigate the complex administrative hurdles required to maintain their eligibility. The paperwork itself becomes the barrier.

So the solution you’re pointing towards is radical simplification, making the help cognitively easy to access and maintain. Essentially, yes. We need streamlined, potentially automated systems where possible.

Think about things like pre-filled application forms using existing government data, digital applications that require minimal user input, clearer, simpler language, maybe shifting towards automatic enrollment for benefits when eligibility is clear from other data sources. The overarching goal has to be minimizing those friction points, reducing the administrative burden down to near zero. And that frees up the individual’s precious mental capacity, allowing them to apply their recovered bandwidth to more strategic life choices, like focusing on education, acquiring new job skills, or simply engaging in more consistent, less stressed parenting.

Okay, so beyond reducing complexity, we also need to tackle the uncertainty factor because that seems to be the primary driver of the chronic stress and the amygdala hijacking you described. The research is very clear on this. Chronic uncertainty is what keeps the brain locked in that damaging high cortisol fight or flight state.

Think about someone working in the gig economy, maybe driving for a rideshare service. Their income can fluctuate wildly from week to week, maybe $800 one week, then only $200 the next. That person is constantly fighting the metaphorical lion.

The prefrontal cortex is under relentless attack from uncertainty about basic survival needs. Which suggests that simply increasing the amount of money people have might not be enough on its own. We also need to prioritize the predictability and stability of that income.

Stability is arguably just as important as the absolute amount, yes. Policies that aim to create stable, predictable incomes, whether that’s through a higher guaranteed minimum wage, maybe forms of predictable basic income or more stable employment contracts, they provide more than just financial stability. They provide crucial peace of mind.

And that peace of mind is the key ingredient that releases cognitive resources back to the PFC, back to the planning and executive function parts of the brain. When that frantic weekly scrambling to make ends meet stops, or at least lessens significantly, the brain can finally use its bandwidth for other things. For planning ahead, for learning new skills, for engaging in consistent, high quality interactions with children, for managing health proactively.

And the power of even small interventions, the things often called nudges, really demonstrates how hungry the brain is for this freed up bandwidth, doesn’t it? Oh, the research on nudges in this context is phenomenal because it often doesn’t require massive government overhauls or huge expenditures. The text message study you mentioned earlier is a perfect illustration. Researchers sent simple, timely text reminders to parents living under conditions of scarcity, just gently prompting them to read to their children that evening.

And the key was the intervention didn’t try to teach them new parenting skills or change their fundamental motivation. These parents already valued reading to their kids and intended to do it. Exactly.

But the cognitive clutter, the sheer mental exhaustion of scarcity, made it easy to forget or feel too drained to actually execute that task consistently. The simple text reminder acted like an external prompt. It cut through the mental noise of the immediate financial crisis and allowed the parents’ existing good intention to be carried out.

And the results were significant. Yes. The resulting gains in the children’s literacy scores were quite significant.

The lesson here is powerful. Don’t necessarily try to teach complex new skills to an already overloaded brain. Sometimes the most effective approach is simply to help that overloaded brain execute the good intentions it already has by reducing the friction, by making it easier.

This all ultimately leads us to the crucial new conversation we really need to be having about poverty. This deeper biological understanding demands a fundamental shift away from judgment and blame. We really have to permanently abandon that judgmental question.

Why do they keep making such bad decisions? That question is not only morally simplistic, it’s scientifically inaccurate and structurally unhelpful. It misses the entire point. And we must replace it with the crucial evidence-based question, the one that demands systemic answers.

What is it about their environment? What is it about the bureaucratic complexity, the lack of predictability, the chronic stress they face? What is it about that environment that is draining their cognitive resources and making good, strategic, long-term decisions so incredibly hard? Recognizing the biological reality of the cognitive tax is truly the essential first step toward designing more compassionate and ultimately more effective system reforms. We start to realize that poverty robs people not only of money and opportunity, but actively scripts them of the core executive functions, the essential mental capacity they desperately need to claw their way out. The climb isn’t just steep financially, it’s being attempted while carrying this invisible, crushing biological weight of cognitive depletion.

It reframes the struggle entirely. It’s not just a physical battle against difficult circumstances, but also a profound and often invisible mental battle against one’s own stress chemistry, against a brain rewired for short-term survival at the expense of long-term progress. Understanding just how much that hidden burden truly weighs.

That seems to be the key to figuring out how we can genuinely help lift it. Well, that was our topic for today from English Plus Podcast, but we’re not done yet. We’ll be back with some useful language focus that will help you also take your English to the next level.

Never stop learning with English Plus Podcast. Have you ever gotten to the end of a really demanding week, maybe even just a long day, and felt so mentally wiped out that making a simple choice felt impossible? Like deciding what to make for dinner or even what to watch. It just feels like lifting weights.

Oh, absolutely. That feeling of total mental drain. Exactly.

But what if that feeling, that heavy cognitive drag, wasn’t just about being busy or multitasking? What if it stemmed from something deeper, like the constant, relentless psychological pressure of, well, of scarcity? The mental effort of just managing when you don’t have enough of something crucial. Yeah, that constant calculation, optimizing every single little resource. And then how do we talk about this? How can using the right words, specific terms like cognitive load or maybe compassionate design help turn complex, sometimes dry scientific research into human stories people can actually connect with? That connection is key, isn’t it? Making the science relatable.

We’re going to dive into the language that tries to bridge that gap, the gap between neuroscience and social policy. Think of it as a kind of shortcut to understanding this hidden mental burden, the one that comes with limited resources. Welcome to Language Focus from English Plus Podcast.

So let’s start by unpacking the tools we even have to discuss this, because we’re really operating at a tricky intersection here, aren’t we? Definitely. You’ve got hard science on one side, neuroscience, cognitive psychology. Right, the brain stuff.

And then on the other side, you have these deeply sensitive, very human social issues like poverty, chronic illness, things that carry a lot of weight. Standing right there at that crossroads. The communication challenge feels, well, huge, wouldn’t you say? It absolutely is.

It’s like walking a tightrope. You need language that’s precise, scientifically accurate. You can’t just fudge the details on how the brain works.

I’ll get the science right. But at the same time, the language has to be evocative. It has to resonate.

If you’re talking about the psychological impact of scarcity, the listener or the reader needs to feel that struggle somehow. Otherwise, it just stays abstract. Clinical.

Exactly. Too clinical and people just tune out. The issue stays over there.

Marginalized, not really understood in a human way. I think the real mission then for the language we use in this space, it’s fundamentally about shifting the narrative, isn’t it? That’s the core of it. We need words, vocabulary that can immediately change how people frame the issue.

Moving the focus away from blaming the individual, their character, their choices, their perceived failings. Away from that judgment frame. And putting it squarely onto the environment.

The pressures that person is actually facing. That’s precisely the goal. And to really appreciate the power of making that shift, we first have to look at the old framework.

The one that often does damage. And there’s probably no better example of that kind of, let’s say, toxic cultural shorthand, especially in the West, than the whole bootstraps myth. Ah, yes.

The classic. The famous or maybe infamous phrase, pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps. We hear it all the time.

In politics, in discussions about opportunity, success. What’s the basic promise packed into that phrase? Well, the promise is that getting ahead, improving your life, it’s purely down to individual effort, just grit, determination, hard work. And crucially, it implies you don’t need any outside help.

No systemic support needed. It taps into that ideal of self-reliance, which sounds appealing. It does sound appealing.

It’s a powerful idiom for that reason. But the article we looked at makes this really critical point, highlighting the impossibility that’s literally built right into the phrase itself. You mean you actually can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps? Physically, no.

That’s the historical irony. The phrase originally described an absurd, impossible task. You can’t lift yourself off the ground by pulling on your own shoelaces.

I never actually thought about the literal meaning like that. Right. But when that phrase gets deployed as cultural shorthand in policy debates or just casual conversation about poverty, it sets this incredibly unrealistic, often quite cruel expectation, especially for people starting out with huge systemic disadvantages.

So it stops being a quirky phrase and becomes almost a weapon. In a way, yes. It functions as this powerful ideological barrier.

It shuts down necessary conversations about things like resource distribution, systemic inequality, the actual support people might need. It frames needing help as a personal failure. It really is the language of judgment, It is.

And the best way to combat that language of judgment is often with the language of science, which brings us neatly to some of the core scientific concepts that help define this invisible struggle we’re talking about. Okay. Let’s start with the big one.

Cognitive load. For anyone listening who isn’t deep into cognitive psychology, how should we define that term? Simply but accurately. Okay.

Cognitive load. Think of it as the total amount of mental effort you’re using right now, specifically in your working memory. Working memory.

That’s like the brain’s RAM, right? The temporary scratch pad where you hold information you’re actively using. Exactly like RAM. Your brain has a finite capacity for processing information and holding ideas consciously at any one time.

When you try to cram too much in or the tasks are too demanding, you exceed that capacity. That’s high cognitive load. We’ve all felt that.

Like trying to follow complicated directions while also listening to someone talk to you and maybe the radio’s on. Perfect example. That’s an acute load.

A temporary spike. You feel overwhelmed for a bit. But the really critical distinction the research makes, especially when we talk about scarcity, is that the load isn’t temporary.

It’s chronic. Ah, okay. That’s the game changer.

It’s not just a bad hour. It is absolutely central to understanding the impact of poverty or any severe ongoing lack of resources. It’s not about juggling emails for an hour at your desk.

It’s the constant 247 mental work required just to manage survival when resources are incredibly tight. Can you give an example of that constant mental work? Think about the nonstop calculations someone might be forced to make. Okay, the gas bill is due.

But payday isn’t for five days. Do I pay it late and whisk a shut off? Or do I skimp on groceries? If I buy the cheaper, less nutritious food, what’s the long-term impact on my kids’ health? If I take the bus to save gas money for the bill, will the unreliable schedule make me late for work, putting my job at risk? Wow. It sounds like your brain is forced to run this incredibly demanding, high-stakes optimization program constantly in the background.

That’s a great way to put it. It’s an always-on app running in your mental background, constantly scanning for threats, calculating trade-offs, juggling impossible choices. It never gets to shut down.

And that must consume a huge amount of mental energy, that processing power that you’d normally use for other things, like planning or learning, or even just relaxing. Precisely. And what’s elegant about the term cognitive load is that, while it is scientifically precise, it’s also become pretty relatable.

People kind of intuitively get it. You can even hear people using it casually now, right? Sorry, I can’t take on another project. My cognitive load is totally maxed out.

Yeah, it’s creeping into everyday language. It successfully translates this complex neurological state into vocabulary that feels, well, understandable. Empathetic, even.

It does. It names the invisible pressure. And what primarily induces that chronic load, in this context, is the psychological state of scarcity itself.

Now, we usually think of scarcity in economic terms, right? Like a shortage of money. That’s the common usage, yeah. Lack of funds.

But the analysis we’re digging into here, it really broadens that definition, doesn’t it? It does, significantly. It elevates scarcity beyond just economics into a powerful psychological concept. It’s the mindset that gets triggered by the perceived shortage of any critical resource.

So it’s not just money. Not at all. You can experience a scarcity of time.

Think about facing an overwhelming deadline at work or school. That can induce the same kind of tunneling focus. The same feeling of depletion.

Right, like all you can think about is finishing that one urgent thing. Exactly. Or you could experience a scarcity of social connection or affection, or even predictability in your environment.

The psychological mechanism, the way it captures your attention and drains resources, seems to be remarkably similar, regardless of the specific resource that’s lacking. That’s fascinating. And this feeling of scarcity, whatever the resource, it forces you into a particular kind of mental state, doesn’t it? You mentioned tunnel vision.

It absolutely does. It powerfully focuses your attention on the scarce resource and the immediate problem it represents. Psychologists and economists talk about how it promotes something called temporal discounting.

Temporal discounting, meaning discounting the future. Essentially, yes. When resources are acutely scarce, your brain heavily prioritizes solving the immediate crisis right now, paying that overdue bill today, finding food for tonight over longer term goals.

So planning for retirement or saving for education or even investing time in preventative health. Those things just fall off the radar. They become cognitive luxuries you literally can’t afford.

The brain, quite adaptively in a way, focuses all its processing power on navigating the present emergency. It’s a survival mechanism. But that intense focus comes at a steep cost.

It consumes the cognitive bandwidth needed for strategic, future-oriented thinking. The scarcity mindset locks you into short-term survival mode. OK, so scarcity creates this chronic cognitive load, this constant mental drain.

What happens to the brain as a result? You made a point earlier that I think is maybe the most important takeaway here. The resulting mental depletion, the changes in thinking or behavior, they are not a character flaw. No, absolutely not.

And this is crucial for changing the public conversation. Instead, you framed it as a physiological adaptation. Can you unpack that a bit more? Sure.

A physiological adaptation is basically any change in how a body functions. It could be structural, it could be chemical, it could be behavioral. That helps an organism survive and cook better within its specific environment.

Like camouflage in an animal. Or a simpler example. Think about your pupils dilating when you walk into a dark room.

Your eyes are automatically adjusting to maximize the available light. That’s not a weakness or a defect in your eyes. It’s your body functioning exactly as it should to adapt to the changed environment.

It’s effective survival. OK, got it. So if we apply that same logic to the brain under conditions of chronic scarcity.

Then we start to see the observed changes. Things like reduced capacity for complex planning, maybe increased impulsivity, that general feeling of mental exhaustion not as signs of moral failure or a lack of willpower. But as a logical biological response.

Yeah. The brain adapting to operate under constant high pressure threatening condition. Precisely.

When you’re under chronic stress, which is exactly what severe resource scarcity generates, your body releases stress hormones like cortisol. Now, a short burst of cortisol can be helpful, gets you ready for action. But constantly elevated cortisol is incredibly taxing.

It drains energy. And that impacts the brain directly. It directly depletes resources in the prefrontal cortex.

That’s the part of the brain responsible for all that higher level stuff. Planning, impulse control, complex decision making are executive functions. So we’re reframing difficulty with planning, not as that person is disorganized, but as that person’s brain is wisely conserving its most precious depleted energy resources for immediate threats rather than wasting them on abstract future calculations.

Exactly. It becomes a resource management problem within the brain driven by the external environment, not an inherent character issue. That shift in framing is everything.

And this scientific reframing helps us understand concepts that many of us experience maybe less chronically, but still recognizably, like decision fatigue. Ah, decision fatigue. It’s so pervasive in modern life, isn’t it? We’re constantly bombarded with choices.

Totally. What’s the core idea there? It’s the measurable decline in the quality of your decisions after you’ve been making choices for a long period. Your capacity for making careful, reasoned judgments literally gets depleted.

It’s that classic feeling you spend all day making complex, important decisions at work. You finally leave feeling drained. You walk into the grocery store, exhausted, and suddenly that candy bar right by the checkout, the one you wouldn’t normally even glance at.

Looks incredibly appealing, irresistible almost. Yeah. That impulse buy feels almost automatic.

That’s decision fatigue in action, your willpower, your ability to exert self-control and resist immediate gratification. It’s like a battery that’s run down after hours of use. Your depleted brain defaults to the easiest, quickest, most immediately rewarding option.

Okay, so take that everyday experience and now amplify it massively. Imagine every single decision you make throughout the day, whether to pay this bill or that one, which is the absolute cheapest source of protein. How to stretch $5 for two days carries huge, potentially devastating long-term consequences.

That’s the reality for someone living under severe scarcity. The chronic high cognitive load leads directly to chronic decision fatigue. And that fatigue, in turn, leads to behaviors that might look impulsive or irrational from the outside.

But are actually a predictable outcome of a brain running on empty. Exactly. The system is overloaded.

And the part of the brain taking the biggest hit from this sustained pressure, as you mentioned, is the prefrontal cortex, the home of our executive function. Right. Executive function.

It’s often called the brains management system or the CEO, like we said. It’s a whole suite of crucial cognitive skills that allow us to control our behavior and pursue goals. What skills are included under that umbrella? Key ones include inhibition, that’s stopping yourself from doing something impulsive or inappropriate.

Working memory, holding and manipulating information in your mind, like when you’re doing mental math. And cognitive flexibility or shifting, being able to switch your attention between different tasks or adapt your thinking to new rules. So when the research says chronic scarcity actually damages executive function, that’s a really precise and, frankly, devastating statement, isn’t it? It’s much more specific than just saying someone has trouble planning.

It is. It means the very mental machinery required to successfully navigate the complexities of modern life planning, saving, resisting temptation, learning new skills, sticking to a budget is being actively compromised by the environmental condition itself. So it’s not just, I find it hard to plan for next year.

It’s deeper. It affects the ability to follow multi-step instructions or to override that urge for immediate relief or to juggle competing demands. The very skills you’d need to escape a situation of scarcity.

Exactly. It creates this cruel feedback loop where the condition of poverty itself degrades the cognitive tools needed to overcome poverty. Wow.

And when that executive function is weakened, it sets people up for difficulty, even when something positive happens, right? Like receiving an unexpected bit of money, a windfall. Yes, the windfall scenario is really telling. A windfall, maybe a small inheritance, a work bonus, even a modest lottery win.

We tend to think of that as a straightforward positive, great problem solved. Right, a chance to get ahead. But for a brain that’s been operating under chronic scarcity, suffering from cognitive depletion and decision fatigue, that moment of opportunity can actually become a kind of trap.

How so? Why might that sudden cash injection lead to spending that outsiders might judge as, you know, frivolous or impulsive? Why not immediately pay down debt or save it? Because the brain is still, in many ways, operating in crisis mode. The executive functions, the part that could sit down, calmly assess and calculate, OK, how do I strategically use this $500 to cover bills for the next three months? A and D put $100 aside for an emergency. That part of the brain is exhausted.

It’s depleted. So it gets overridden. It gets overridden by the more immediate drive for relief.

Spending that money on something tangible, something desired for a long time, even if it’s not sensible by external standards, might offer a powerful, immediate reduction in stress, a moment of feeling normal, a brief escape from the constant pressure. The depleted mind desperately craves that relief. So the spending isn’t necessarily irrational from the perspective of the brain’s immediate need, even if it looks counterproductive long term.

Exactly. It’s a tragic, but from a neuropsychological standpoint, a completely understandable behavioral outcome of severe cognitive depletion. It highlights the deep impact of scarcity on decision-making capacity itself.

OK, this paints a clear picture of the problem. So let’s shift from diagnosis, understanding the chronic cognitive load and its effects into the solution space. And here, the language seems to change quite dramatically.

It moves towards ideas from policy, from design, even from business, in terms like streamlined and automated. Yes, this is where the language aims to become actionable. It moves from observation to essentially engineering.

We start talking about how to design systems differently. So streamlined, what does that mean in this context? To streamline something is basically to make it more efficient and effective, usually by simplifying the process, removing unnecessary steps, getting rid of bottlenecks. Think about streamlining a manufacturing process to make it faster and cheaper.

OK, and automated? To automate is to set up a process so it operates automatically with minimal need for human intervention or, crucially here, minimal mental effort from the user. And why is applying this kind of business or tech vocabulary so important when we’re talking about social policy, like welfare programs or assistance applications? Because if you accept the premise that the people needing these services are likely already operating at or near 100% cognitive load, then the system designed to help them absolutely must not add to that burden. Precisely.

A welfare application form that’s 40 pages long, written in dense legalese, requires five different obscure forms of proof and makes you take repeated trips to an understaffed office during working hours. That system is actively working against the user’s cognitive capacity. It’s actively punishing them for needing help by compounding the very problem of the mental overload that they’re seeking relief from.

It’s fundamentally poor design, given the user’s likely state. So, applying the idea of streamlining means treating, say, a government benefits application with the same kind of user-centered design thinking that a company like Amazon or Apple puts into their apps. That’s the core idea.

Make it simple. Make it intuitive. Make the default options the helpful ones.

Reduce the number of clicks, the number of questions, the number of hurdles. Recognize that every single extra step, every confusing question, every requirement to manually remember to renew something. It’s effectively a tax.

A tax levied directly on the user’s already depleted cognitive resources. So by streamlining and automating things like maybe automatically renewing benefits based on tax data the government already has, or allowing single click verification where possible. You are literally reducing the amount of mental effort required just to access basic support.

You’re freeing up precious cognitive bandwidth that the person can then potentially use for other things like finding work, managing health, or caring for family. It’s about reducing the hassle factor which is actually a cognitive burden factor. Exactly.

And the umbrella term that captures this whole intentional user-focused approach is compassionate design. That’s such an interesting term because it fuses an emotional concept, compassion, feeling for others with a very active, practical, almost technical concept design. Right.

The power of compassionate design lies in that fusion. It demands action. It’s not just about feeling sympathy for someone’s situation which is passive.

It’s about actively building the system, engineering the process with the user’s likely emotional and cognitive state factored in right from the very beginning. Yes. It’s about anticipating the user’s needs and limitations and designing for them, not despite them.

Okay, but let me push back on this a little. When we talk about streamlining, automating, making things ruthlessly efficient, isn’t there a risk? Could this kind of compassionate design accidentally become just cold, efficient design? That’s a really important question, a necessary one. Could we end up removing the crucial human element, losing the space for nuance, for discretion, for handling the complex cases that don’t fit neatly into an algorithm Does automation risk creating an even more frustrating, faithless bureaucracy? It’s a definite potential pitfall.

Absolutely. Creating cold, unfeeling efficiency is a risk if automation is implemented poorly. But I would argue that true compassionate design actually anticipates and guards against this.

The goal isn’t necessarily to replace all human interaction. It’s often to redirect it more effectively. The design principle should be that the vast majority of straightforward, simple, clear-cut cases say a single parent with stable, low income applying for basic food aid, those should be as frictionless and automated as possible.

So that frees up resources. Exactly. It frees up the limited time and expertise of the human workforce, the social workers, the case managers, the policy experts, so they can dedicate quality, in-depth attention to the genuinely complex, messy, nuanced cases.

The ones that do require human judgment, empathy, and discretion. Ah, I see. So it’s not about getting rid of the humans.

It’s about redesigning the system so the humans aren’t bogged down in processing routine paperwork and can instead focus their skills where they’re most critically needed. Precisely. Think of the analogy used in the article.

It’s the difference between finishing construction on a building and then realizing you need wheelchair access so you kind of bolt on a functional but maybe ugly ramp as an afterthought. That’s like charity, a patch. Versus designing the building from the initial blueprint stage to be inherently beautiful, functional, and universally accessible with gentle slopes integrated into the landscaping, wide automatic doors, elevators, clear signage access built in as a core feature, not an add-on.

That’s compassionate design. Making accessibility, simplicity, and crucially low cognitive burden the default setting for how you interact with the system. Yes.

It makes needing help less effortful, less stressful, less taxing on already strained mental resources. That distinction between passive charity or afterthought fixes and active, intentional, engineered compassion feels really profound. It changes the whole conversation about policy from just a moral debate about who deserves help into a practical design challenge.

Yeah. How do we build systems that actually work for the humans who need them most? That’s the power of the right language. It reframes the entire problem.

Okay, so we’ve built up this really powerful vocabulary now. Cognitive load, scarcity mindset, decision fatigue, compassionate design to define the struggle and point towards solutions. Let’s switch gears slightly.

How do we actually communicate these complex ideas effectively? How do we make them resonate with people who aren’t scientists or policy wants? Ah, the communication challenge. This is all about bridging that divide, right? Between the detailed scientific paper and, well, public understanding and empathy. Yeah.

What’s the goal when you’re trying to communicate this kind of human behavior science? You’re always aiming for that sweet spot. You absolutely have to be accurate. You can’t misrepresent the science of, say, executive function just to make it sound simpler.

That does a disservice to the research. So accuracy is non-negotiable? Right. But at the same time, it has to be instantly relatable.

If your explanation sounds like it’s lifted straight from a dry textbook, you lose people. Their eyes glaze over. But if you oversimplify it too much? Then you risk trivializing the issue, losing the scientific weight and credibility.

It’s a real balancing act. And probably the single best tool we have in our communication toolkit for hitting that sweet spot, for making the complex relatable without losing accuracy, is the good old analogy. Absolutely.

Analogies are the workhorses of explanation, aren’t they? They really are. How would you define what an analogy does functionally? Well, it’s essentially a comparison between two things that might seem quite different on the surface but share some underlying structural similarity. And you make that comparison purely for the purpose of explaining or clarifying the more complex or abstract concept.

So it takes something unseen or hard to grasp, like the internal feeling of mental effort. And it bridges it directly to a familiar, everyday experience or object. It makes the abstract suddenly concrete and visible in the listener’s mind.

The article we discussed uses a couple of really powerful ones. The core analogy for explaining the chronic nature of cognitive load under scarcity. Comparing the brain to a computer.

The computer running too many demanding applications with not enough RAM. It’s brilliant, because almost everyone has experienced that frustration. Totally.

You try to stream a movie, run a complex game, maybe have a bunch of browser tabs open, and your antivirus decides to scan. And the whole system just grinds to a halt. It lags, it freezes, maybe it even crashes.

And the key insight is the computer itself isn’t necessarily broken or defective. It’s just that the demands being placed on it exceed its available processing resources, its RAM. Exactly.

And applying that back to scarcity is so powerful. It immediately suggests the brain isn’t inherently defective. It’s not lazy or weak.

It’s simply being asked to run too many critical, high-stakes background calculations all at once with insufficient resources. So naturally it slows down. It struggles with complex, future-oriented tasks.

It instantly removes that layer of moral judgment. It becomes a resource issue, not a character issue. Precisely.

And the second key analogy that really lands is the one for decision fatigue. Comparing willpower or self-control to a smartphone battery. Ah, yeah, the battery analogy.

That one feels very intuitive too. Right. You start the day, metaphorically, with a full charge, 100%.

But every decision you make, every time you exert self-control, resisting that donut, forcing yourself to write that difficult email, navigating stressful traffic patiently, it drains a little bit of that battery. Uses up some juice. Uses up juice.

So by late afternoon, or especially in the evening after a long day of choices, you find yourself in the red zone, low power mode. And what happens in low power mode? Well, on your phone, the operating system starts restricting functions to conserve energy, maybe it dims the screen, stops background updates. Your brain does something similar.

When willpower is depleted, complex, deliberation-resisting impulses, those become too energy expensive. So you default to the easy choice, the immediately gratifying one, like the candy bar at the checkout. Exactly.