- MagTalk Audio Episode

- The Stone Mothers: The Era of Containment

- The Modern Revolution: Healing by Design

- The Urban Anxiety Machine

- Reclaiming the Horizon

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: An Interview with Florence Nightingale

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

MagTalk Audio Episode

There is a feeling you get when you walk into a government building, a specific kind of heaviness that settles in your chest. The ceilings are low, the lights buzz with a headache-inducing hum, and the walls are painted a color that can only be described as “bureaucratic beige.” You feel small. You feel managed. You feel like a number on a spreadsheet. Now, contrast that with walking into a cathedral, or a modern museum, or a library with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking a park. Your shoulders drop. Your breathing slows down. You feel, for lack of a better word, human again.

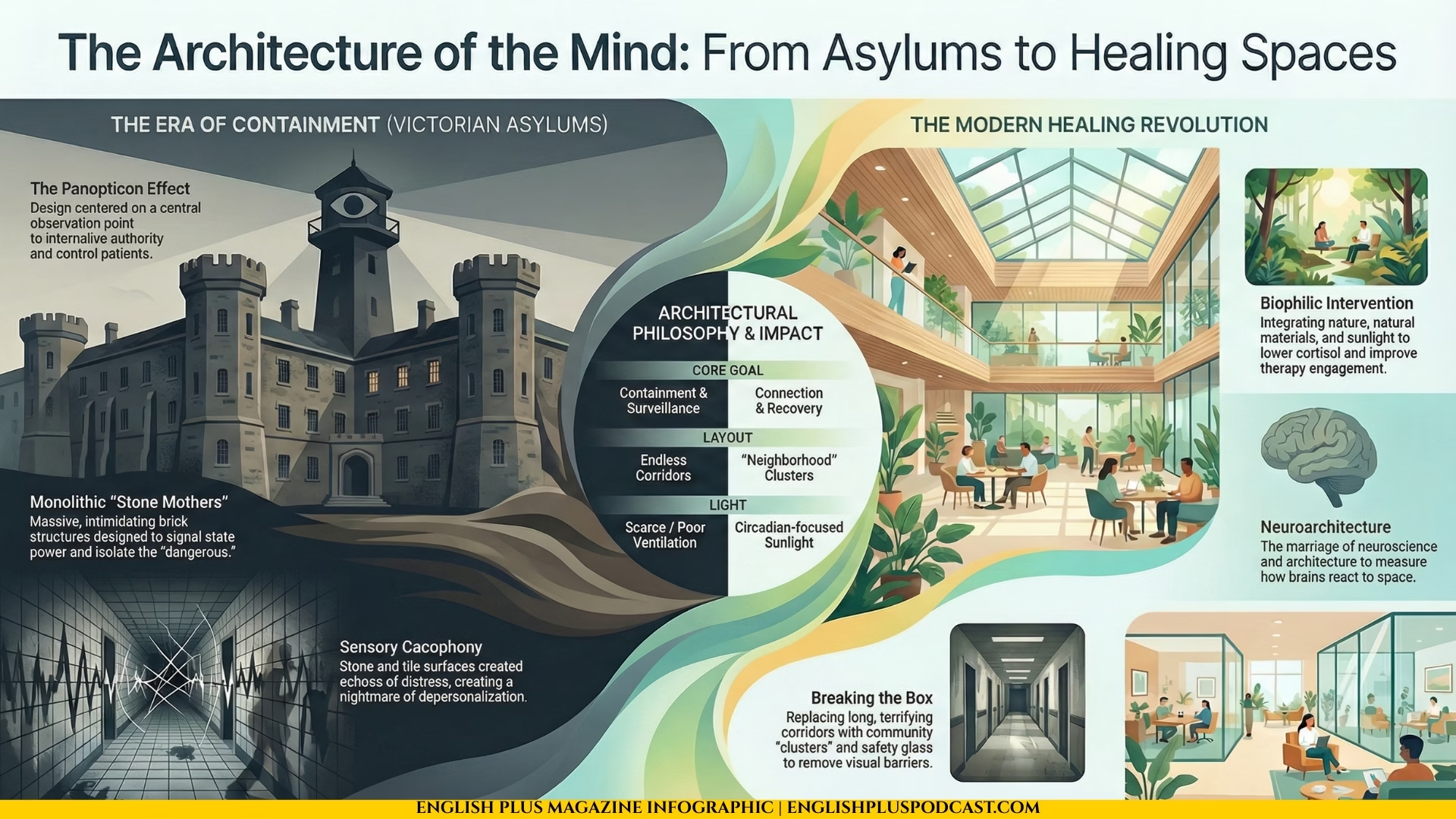

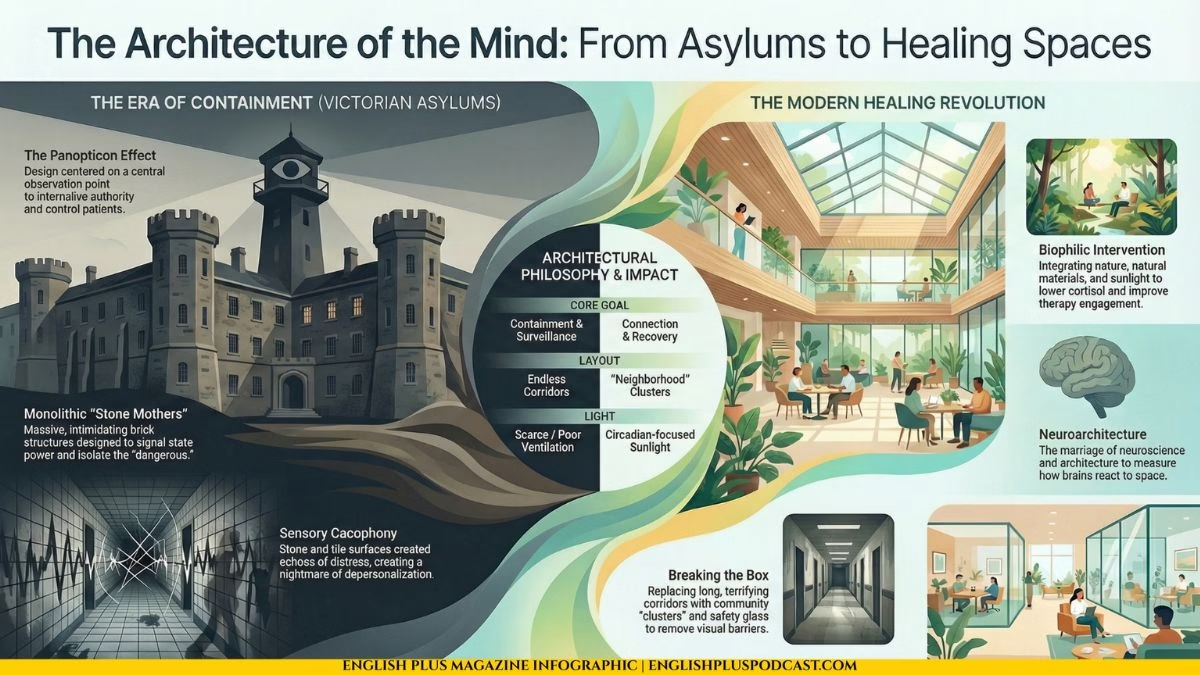

We tend to think of architecture as a container—a box where life happens. But architecture is not just a backdrop; it is an active participant in our psychological lives. Winston Churchill famously said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” And nowhere is this more profoundly true, and more historically tragic, than in the way we have built spaces to treat the human mind. The history of mental health architecture is a physical map of our empathy, or lack thereof. It is a journey from the terrifying, monolithic stone mothers of the Victorian era to the light-filled, biophilic healing centers of today. But as we tear down the old walls, we have to ask: are our modern cities just open-air asylums?

The Stone Mothers: The Era of Containment

The Psychology of the Brick

If you drive through the countryside of England or parts of the American Northeast, you might stumble upon them. Massive, red-brick leviathans sitting on hilltops, looming over the town below like sleeping giants. These were the Victorian Asylums. When they were built, they were actually seen as progressive. Before them, the “mad” were kept in cellars or prisons. The asylum was meant to be a refuge—a place of “asylum” in the literal sense.

But the road to hell is paved with good blueprints. The architecture of the 19th-century asylum was designed around a very specific philosophy: containment and surveillance. They were built to impress and to intimidate. The sheer scale of these buildings was meant to signal the power of the state and the benevolence of society, but to the person inside, the scale was crushing. Long, endless corridors—some stretching for a quarter of a mile—were designed to facilitate the movement of staff, but for the patient, they became tunnels of depersonalization. To walk down a corridor that never seems to end is a nightmare made real.

The Panopticon Effect

The guiding principle of this architecture was the Panopticon. This concept, developed by philosopher Jeremy Bentham, involves a central observation point from which a guard can watch all inmates without them knowing if they are being watched. This internalized the gaze of authority. In the asylum, architecture was the primary method of control. High walls, barred windows, and heavy doors weren’t just security measures; they were psychological enforcers. They told the patient, “You are dangerous. You are separate. You do not belong to the world.”

The ventilation was poor, the light was scarce, and the acoustics were catastrophic. Imagine a hall of stone and tile. Now imagine it filled with the sounds of human distress. The echo created a cacophony that could drive a sane person to the brink. We treated the mind by trapping it in a box that amplified its torment. We assumed that to cure the chaotic mind, we needed to impose rigid, geometric order. We were wrong.

The Modern Revolution: Healing by Design

Breaking the Box

It took us a long time to realize that you cannot cure darkness with more darkness. The shift began in the mid-20th century, but it has really accelerated in the last two decades with the rise of a field called “neuroarchitecture.” This is exactly what it sounds like: the marriage of neuroscience and architecture. We started measuring how the brain reacts to space, light, and texture.

The results were undeniable. Patients in rooms with windows looking out at trees recovered faster and required less pain medication than those looking at brick walls. Sunlight resets our circadian rhythms, which is crucial for mental stability. Suddenly, the “healing center” replaced the “asylum.”

The Biophilic Intervention

Modern mental health facilities look less like prisons and more like universities or spas. The bars are gone, replaced by safety glass that creates an invisible boundary without the visual language of incarceration. The long, terrifying corridors are broken up into “clusters” or “neighborhoods” to create a sense of community rather than a processing plant.

But the biggest shift is “biophilic design”—our innate biological connection to nature. We are not meant to live in concrete cubes. We are biological organisms that evolved on the savannah. We crave the complex fractal patterns of leaves, the sound of water, the variability of natural light. Modern clinics are integrating internal courtyards, healing gardens, and natural materials like wood and stone (the warm kind, not the prison kind).

This isn’t just aesthetic; it’s medical. When you lower cortisol levels through design, therapy works better. When a patient feels respected by the space they are in, they are more likely to engage in their own recovery. The building says, “You are worth this beauty.” That message alone is a powerful antidepressant.

The Urban Anxiety Machine

The Canyons of Steel

However, just as we are fixing our hospitals, we might be breaking our cities. Most of us don’t live in healing centers; we live in the metropolis. And for many, the modern city is an anxiety machine. We have traded the high walls of the asylum for the high rises of the financial district, but the effect on the nervous system can be surprisingly similar.

Urban crowding creates a paradox: we are surrounded by millions of people, yet we feel profoundly isolated. This is “crowded isolation.” The architecture of the modern city is often hostile to human connection. We build vertical silos where neighbors share a wall but never a word. We build “defensive architecture”—benches designed so you can’t sleep on them, spikes on ledges to prevent sitting. This signals a society of distrust. When the environment treats everyone like a potential nuisance, we start to feel like nuisances.

Sensory Overload and the Green Deficit

Furthermore, the city is a sensory assault. The constant noise, the flashing lights, the lack of horizon—it puts the brain in a state of hyper-arousal. We are constantly scanning for threats. We are not designed to process the amount of data a city street throws at us in ten seconds. This chronic low-level stress creates a background hum of anxiety that we just accept as “normal.”

The lack of green space is not a luxury issue; it is a public health crisis. Trees in a city are not just decoration; they are the lungs of the neighborhood, and I don’t just mean for oxygen. They are visual softeners. They break up the hard lines of steel and glass. Without them, the brain has nowhere to rest. We are seeing a direct correlation between the “concrete jungle” and rising rates of anxiety and depression. We have dismantled the asylum, only to turn the entire world into a stress test.

Reclaiming the Horizon

The Future of Feeling

So, where do we go from here? The future of mental health isn’t just in a pill bottle; it’s in the blueprint. We need to demand “psychologically sustainable” architecture. This means designing schools that don’t look like factories, offices that don’t look like hives, and cities that prioritize the pedestrian over the car.

We need spaces that allow for “prospect and refuge”—a biological need to see the horizon (prospect) while feeling protected from behind (refuge). We need to reintroduce chaos—the good kind, the organic kind—into our sterile grids.

The buildings we inhabit are the silent partners in our lives. They whisper to us all day long. For too long, they have been whispering, “Obey,” “Work,” “Fear.” It is time we built structures that whisper, “Breathe,” “Connect,” “Live.” Because if we are going to heal the mind, we have to start by healing the place where the mind lives.

Focus on Language

Let’s dive right into the language we used in this piece because, honestly, the words we use to describe spaces are just as important as the bricks we use to build them. I want to start with that heavy, imposing word I used early on: Monolithic. I called the Victorian asylums “monolithic stone mothers.” A monolith is literally a single great stone, but in conversation, we use it to describe something massive, uniform, and characterless. It suggests something that cannot be moved or changed. You might describe a corporation as monolithic if it feels huge and unresponsive, or a government agency that just won’t budge. It’s a great word when you want to convey size that feels oppressive.

That leads me perfectly to the concept of the Panopticon. Now, this is a specific historical term, but it’s incredibly useful in modern life. It refers to a circular prison with a watchtower in the middle, but metaphorically, it describes any situation where you feel constantly watched but can’t see the watcher. We live in a digital Panopticon today with social media and surveillance cameras. You can use this when you’re at work and your boss monitors your keystrokes. You could say, “This office feels like a Panopticon; I can’t breathe without someone knowing.” It adds a layer of intellectual paranoia to your description.

I also used the word Cacophony. I love the sound of this word; it sounds exactly like what it means. A cacophony is a harsh, discordant mixture of sounds. It’s the opposite of a symphony. The asylum corridors were a cacophony of distress. In real life, you might walk into a kindergarten class at recess or a busy stock trading floor and describe it as a cacophony. It’s chaos for the ears. Use it when “loud” just isn’t descriptive enough.

Then we swung to the positive side with Biophilic. This comes from “bio” (life) and “philia” (love). It’s the love of living things. Biophilic design incorporates nature. But you can have a biophilic reaction to things. If you’re the type of person who needs to fill your apartment with fifty house plants to feel sane, you are satisfying a biophilic urge. It’s a sophisticated way to explain why we like ocean views and wooden floors. We aren’t just being fancy; we are being biological.

Let’s talk about Circadian. I mentioned “circadian rhythms.” This refers to physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a daily cycle, mostly responding to light and darkness. But in casual English, we use it to talk about our sleep-wake energy. If you fly to a different time zone, your circadian rhythm is wrecked. If you work the night shift, you are fighting your circadian nature. It’s a scientific word that has earned its place in everyday complaints about being tired.

I used the phrase Sensory Overload. This is when your five senses—sight, hearing, smell, touch, taste—take in more information than your brain can process. The city causes sensory overload. But so does a shopping mall on Black Friday. So does scrolling TikTok for three hours. It’s a state of mental exhaustion caused by too much input. You can use this to politely excuse yourself from a chaotic party: “I’m getting a bit of sensory overload, I need to step outside for fresh air.”

Another great structural word is Edifice. While it means a building, usually a large and imposing one, we often use it metaphorically to describe a complex system of beliefs. You might talk about the “edifice of the legal system” or the “edifice of lies” a politician built. It implies something constructed that is complicated and maybe a bit intimidating.

We discussed Gentrification, though implicitly, when talking about urban spaces. Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses. It’s a hot-button word. It usually implies that the original, poorer residents are being pushed out. You hear this word in almost every major city discussion today. “This coffee shop is a sign of gentrification.” It’s vital for social commentary.

I want to highlight Claustrophobia. Most people know this as the fear of small spaces. But in the article, we talked about a psychological claustrophobia caused by the “canyons of steel.” You can be claustrophobic in a relationship, in a job, or in a lifestyle. It’s the feeling of being trapped, of the walls closing in. “I quit my corporate job because the bureaucracy gave me claustrophobia.”

Finally, let’s look at Ameliorate. I didn’t use this explicitly in the text but it fits the theme perfectly. To ameliorate means to make something bad better. Healing architecture ameliorates suffering. A good cup of tea can ameliorate a bad morning. It’s a formal, lovely word for “improve,” but specifically improving something negative.

Now, for the speaking section. I want us to practice describing atmosphere. This is a key speaking skill—moving beyond “it was nice” or “it was bad.” I want you to go to a place in your city—a library, a train station, a cafe—and do a “Sensory Audit.”

Here is the challenge: Sit there for five minutes. Don’t look at your phone. Look at the architecture.

Then, I want you to record a voice note for one minute answering this: “How does this ceiling height make me feel? What is the lighting doing to my mood? Is the sound a cacophony or a hum?”

Use the words Monolithic, Sensory Overload, or Biophilic if they apply. For example: “I’m sitting in the central station. It feels monolithic and cold. The noise is a total cacophony, and the lack of windows is giving me a bit of claustrophobia. I need some biophilic relief.”

Try this. It forces you to connect your vocabulary to your physical reality.

Critical Analysis

Now, let’s step back. I’ve painted a very clear picture here: Victorian Asylums were bad, dark, and evil; Modern Healing Centers are good, light, and virtuous. But if you have been reading my work for long, you know I don’t like leaving things in black and white. Let’s play the devil’s advocate and poke some holes in this “Architecture of Care” narrative. We need to exercise some healthy skepticism.

First, we need to address the Class Issue, or what we might call the “Gentrification of Health.” It is wonderful to talk about biophilic design, atrium gardens, and private rooms with views of the forest. But who gets to access these facilities? The examples of “healing architecture” we see in architectural digest magazines are almost exclusively private clinics or flagship research hospitals in wealthy areas. The reality for public mental health facilities often remains grim, not because of a lack of design knowledge, but because of a lack of funding. By focusing so heavily on architecture, are we distracting ourselves from the systemic issue of access? A beautiful building is useless if your insurance doesn’t cover the entry fee. We risk creating a two-tier system where the rich get “healing centers” and the poor get “holding cells,” regardless of what we know about design.

Secondly, let’s challenge the “Open Space” Dogma. The modern trend is all about open plans, glass walls, and visibility. We frame this as “destigmatizing” and “connecting.” But is total visibility always good for someone in a mental health crisis? Imagine you are experiencing acute paranoia or mania. The last thing you might want is an open, glass-walled room where you feel exposed to everyone. The Victorian asylum, for all its faults, offered walls. It offered separation. There is a safety in being hidden sometimes. Some critics argue that modern “transparent” architecture is just a prettier version of the Panopticon—surveillance dressed up as “light.” We have to ask: does the patient want to be seen, or does the architect just want to see through the building?

Third, we should question the Fetishization of Nature. We have latched onto “biophilia” as a cure-all. Put a plant in the corner, and the depression vanishes! But this can be a dangerous oversimplification. Mental illness is complex, involving neurochemistry, trauma, and sociology. Architecture is a tool, not a doctor. There is a risk that by over-emphasizing the environment, we under-emphasize the need for rigorous medical and therapeutic care. A garden is nice, but it doesn’t cure schizophrenia. We must be careful not to fall into architectural determinism—the belief that the building causes the behavior. A bad building makes things worse, yes, but a good building is not a lobotomy or a pill.

Finally, let’s look at the Demonization of the City. I spent a lot of time calling the city an “anxiety machine.” And while the sensory overload is real, cities are also the engines of human creativity, connection, and resilience. Rural areas, while “biophilic,” often suffer from higher rates of isolation-based depression and suicide than cities do. The “canyons of steel” also contain communities, art scenes, and support networks that you cannot find in a forest. Maybe the anxiety we feel in cities isn’t just about the buildings; maybe it’s about the economic pressure of modern capitalism. Blaming the concrete might be a way of avoiding blaming the culture of overwork.

So, while architecture matters, it is not the only variable. We need to think critically about who pays for these buildings, who designs them, and whether a pretty view is a substitute for real justice.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to get you thinking and debating in the comments. I don’t want the easy answers; I want you to dig deep into your own experiences.

1. Is privacy more important than safety in mental health design?

Modern hospitals use glass walls so nurses can see patients to prevent self-harm. But this kills privacy. If you were a patient, would you trade your dignity for your safety? Where is the line?

2. Does your home make you happy, or just house you?

Look around your own living space. Do you have “biophilic” elements? Is the lighting harsh? We often blame our mood on our jobs or relationships, but how much is your apartment to blame? What is one cheap change you could make today?

3. Should we preserve old asylums or demolish them?

Many old Victorian asylums are being turned into luxury apartments. Is this a beautiful reclaiming of history, or is it deeply disrespectful to the suffering that happened there? Would you live in a converted asylum?

4. Is the “Metaverse” the ultimate solution or the ultimate problem?

If we can build perfect, soothing, biophilic worlds in Virtual Reality, does physical architecture still matter? Could we treat anxiety by putting people in a “perfect” VR forest, or is that a dystopian nightmare?

5. Who owns the “View”?

In cities, access to sunlight and green views costs money. The poor often live in basements or facing brick walls. Should access to sunlight be a legal human right in building codes, or is it just a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder?

Fantastic Guest: An Interview with Florence Nightingale

Danny: Welcome to our Fantastic Guest section. In our main feature, “The Architecture of Care,” we explored how buildings can either drive us crazy or help us heal. We looked at the grim history of the Victorian asylum and the hopeful future of neuroarchitecture. But to truly understand the foundation of this conversation, we need to go back to the woman who practically invented the idea that a hospital’s design is a matter of life and death.

She is known to history as “The Lady with the Lamp,” a gentle angel gliding through the wards of the Crimean War. But the real woman was something far more formidable: a ruthless statistician, a brilliant architectural theorist, and a reformer who had absolutely zero patience for bureaucratic incompetence. She understood that fresh air, light, and space were not luxuries, but medical necessities, a century before neuroscience proved her right. Please welcome the Mother of Modern Nursing, Florence Nightingale. Florence, it is an honor.

Florence: Please, Danny. “The Lady with the Lamp” was a journalistic invention to sell newspapers. I was the Lady with the Pie Chart. I was the Lady with the Scrubbing Brush. The lamp was just necessary because the army refused to pay for candles.

Danny: Noted. I’ll retire the angel imagery immediately. Florence, I brought you here because we’re discussing the “Stone Mothers”—those massive, terrifying Victorian asylums. You lived in that era. You walked those halls. When you read my article about the “psychology of the brick,” what went through your mind?

Florence: Validation, mostly. And a profound sense of exhaustion. I spent fifty years screaming into the void that you cannot cure a patient by sealing them in a stagnant box of their own exhalations. The Victorian architects… they were obsessed with the exterior. They wanted the asylum to look like a castle, to impress the local governors. They forgot that inside the castle, human beings had to breathe.

Danny: We talked about how those buildings were designed for containment. High walls, small windows.

Florence: They were designed for death. I once calculated that the mortality rate in some of London’s hospitals was higher than the mortality rate of soldiers on the battlefield. Think about that. You were safer facing a cannon than you were checking into a hospital. Why? Because the architecture was lethal. They built wards with no cross-ventilation, so the “foul air”—what we called miasma—just sat there, rotting. They put the latrines next to the kitchens. They designed buildings that were essentially Petri dishes before we even knew what a Petri dish was.

Danny: You mentioned “miasma.” Now, we know today that miasma—the idea of “bad air” causing disease—was scientifically incorrect. It was germs. Bacteria.

Florence: Oh, stop it. You moderns are so arrogant with your microscopes. Yes, I was wrong about the mechanism. I thought it was the smell; it turned out to be the invisible bugs. But was I wrong about the solution?

Danny: No. You were exactly right.

Florence: Precisely. I demanded open windows. I demanded sunlight. I demanded scouring the floors. Whether you do that to remove “miasma” or to kill “bacteria,” the result is the same: the patient lives. I find it hilarious that your “neuroarchitecture” is now publishing studies saying, “Oh, look, sunlight helps patients recover.” I wrote that in Notes on Nursing in 1859! “It is the unqualified result of all my experience with the sick, that second only to their need of fresh air is their need of light.” I didn’t need an fMRI machine to tell me that. I just needed eyes.

Danny: That’s the “Biophilic” design we talked about. Humans needing nature. You were huge on that. You famously said that the variety of form and color in objects presented to patients are actual means of recovery.

Florence: Because the mind and the body are not separate entities, Danny. This is the great mistake of your century. You treat the body like a car—you take it to the mechanic, fix the carburetor, and ignore the driver. The sick person is an entire ecosystem. If the eye looks at a gray wall for six weeks, the mind turns gray. If the mind turns gray, the immune system surrenders. I have seen soldiers die simply because they lost the will to look at another blank ceiling. And I have seen men come back from the brink of death because someone put a vase of wildflowers on their bedside table.

Danny: So, let’s talk about the modern hospital. Have you seen what we’ve built?

Florence: I have. And I am horrified.

Danny: Really? But they’re so sterile. They’re so clean.

Florence: They are factories. I visited—spiritually speaking—a modern Intensive Care Unit. It is a windowless dungeon filled with beeping machines. The lights are artificial and hum constantly. The air is recycled. There is no day, no night, only the eternal, buzzing “now.” You have swapped the filth of the Victorian era for the sensory torture of the modern era. How is a mind supposed to heal when it is being assaulted by electronics 24 hours a day?

Danny: We call that “Sensory Overload” in the article.

Florence: I call it barbarism. You have prioritized the machines over the men. You design the room around the ventilator, around the monitor, around the cables. The patient is just an accessory to the equipment. In my pavilion design—which I fought very hard for—the bed was the center. The window was the priority. The view of the sky was the medicine. You have made the medicine the medicine, and forgotten that the environment is the spoon that helps it go down.

Danny: That’s a powerful image. “The environment is the spoon.” But Florence, the Pavilion Style—those long, open wards with thirty beds—we criticized that in the article too. We talked about the lack of privacy. The Critical Analysis section argued that open plans can be like a Panopticon, where you’re always watched.

Florence: Privacy! You moderns are obsessed with privacy. You would rather die alone in a private room than recover in company. Let me tell you something about the open ward. Yes, it allowed the nurse to supervise—which is essential, by the way. If I can’t see you, I can’t save you when you stop breathing. But it also created a community of suffering.

Danny: A community of suffering? That sounds bleak.

Florence: It isn’t. It’s human. In Scutari, the men helped each other. The man with the leg wound would read to the man with the eye wound. They shared their fears. They joked. They regulated each other’s behavior. In your modern private rooms, a patient lies alone with their anxiety. Isolation is the incubator of madness. You have confused “dignity” with “solitude.” They are not the same thing.

Danny: That’s a fascinating pushback. We assume privacy is the ultimate luxury. You’re saying it’s a form of solitary confinement.

Florence: I am saying that “The Architecture of Care” must balance the need for rest with the need for connection. Your article mentions “crowded isolation” in cities. You have managed to replicate that in your hospitals. Everyone has a private room, and everyone is lonely. I would argue for a mix. Give them a private nook, yes. But give them a common space. Give them a hearth.

Danny: A hearth? In a hospital?

Florence: Why not? Fire is life. Watching a fire is the oldest form of television. It calms the nervous system. But of course, you can’t have fire because of your oxygen tanks. So you give them a television mounted on the wall showing soap operas. It is not an improvement.

Danny: I want to pivot to the “Urban Anxiety Machine.” You lived in London at the height of the Industrial Revolution. It was dirty, crowded, smoky—probably worse than any modern city.

Florence: It was hell with the lid off. The smog—the “pea-soupers”—was so thick you could taste the coal on your tongue.

Danny: So how did you cope? How did you maintain your sanity in that environment?

Florence: I didn’t. Not entirely. I spent the last several decades of my life largely bedridden. Some say it was Brucellosis I caught in the Crimea. Some say it was PTSD. Some say it was a strategic withdrawal so I could work without being interrupted by fools.

Danny: Strategic withdrawal. I like that. “Sorry, I can’t come to your party, I’m strategically withdrawing.”

Florence: It is highly effective. But because I was confined to my room, I became hyper-aware of my immediate environment. My room at South Street… I curated it like a laboratory of peace. I had specific flowers sent from the country. I had the windows positioned to catch the specific afternoon light. I realized that when the world outside is a chaotic machine, the domestic interior must be a fortress of calm.

But for the poor? For the people in the tenements? They had no fortress. They had damp walls, no light, and noise. And I saw the result. The drunkenness, the violence, the despair. You call it “anxiety” or “depression.” I called it the natural reaction of a human soul to an unnatural habitat. You cannot stack people like firewood in damp cellars and expect them to act like civilized gentlemen.

Danny: You were a data nerd, Florence. You invented the polar area diagram—the “Rose Diagram.” You used statistics to shame the British government into changing policies. If you were looking at the data today—the rising suicide rates, the anxiety prescriptions—what graph would you draw?

Florence: I would draw a correlation between “Screen Time” and “Despair.” I would draw a correlation between “Square Footage of Green Space” and “Mental Health Admissions.” The data is screaming at you, Danny.

I used statistics because the generals and the politicians didn’t care about feelings. If I said, “The soldiers are sad,” they laughed. If I said, “You are losing 40% of your fighting force to preventable disease and it is costing the Crown X million pounds,” they listened.

You need to do the same with architecture. Stop telling developers that green space is “nice.” Tell them that a lack of green space is costing the economy billions in lost productivity and healthcare costs. Monetize the suffering. It’s the only language bureaucrats speak.

Danny: That is incredibly cynical and incredibly practical. “Monetize the suffering.”

Florence: I am not a sentimental woman, Danny. I am a pragmatic one. If you want to build the “Architecture of Care,” you have to prove that the “Architecture of Neglect” is too expensive to maintain.

Danny: Let’s talk about the “Asylums” specifically. In the article, we discuss how they are being turned into luxury apartments. You know, “Live in the historic High Royds Hospital!” High ceilings, exposed brick… and a history of lobotomies. What do you think of that?

Florence: It is… ghoulish. But it is also efficient. I admire efficiency. The buildings themselves—the “Stone Mothers”—were actually built with very high standards of craftsmanship. They have good bones. Better bones than your modern drywall condos.

But there is a spiritual residue. I believe that buildings hold memory. If you live in a room where someone spent thirty years staring at a wall in agony, do you not feel that? I suppose if you put enough beige furniture and potted plants in, you can mask anything. It is the ultimate act of gentrification—evicting the ghosts to make room for the yuppies.

Danny: “Evicting the ghosts to make room for the yuppies.” That needs to be on a t-shirt.

Florence, I want to ask about the “Panopticon” idea. You were a nurse. You watched people. Was your watching benevolent?

Florence: Observation is the primary duty of a nurse. But there is a difference between “watching over” and “watching.”

The Panopticon—Jeremy Bentham’s idea—is about power. It says, “I see you, so you better behave.”

Nursing observation is about protection. It says, “I see you, so you are safe.”

The architecture must communicate the difference. If the nurse’s station is a glass fortress in the middle of the room, that is power. If the nurse is sitting in a chair by the bedside, that is care. It is about proximity. You cannot care for someone from a control tower. You have to be in the trenches.

Danny: We have a lot of architects and designers who read this column. If you could give them one command—one “Nightingale Law” for designing the future of mental health spaces—what would it be?

Florence: Variety.

The sick mind is stuck in a loop. Depression is a loop. Anxiety is a loop. It is the same thought, the same fear, repeating over and over.

The architecture must break the loop. It must offer variety. A view of a cloud moving. A shadow changing on the floor. A texture that feels rough, then smooth.

Do not build perfect, static boxes. Build spaces that change. Build spaces that breathe. Because life is change. If the building is static, it reinforces the death-like stasis of the depressed mind.

And for God’s sake, open a window.

Danny: Open a window. It sounds so simple.

Florence: The truth usually is. We complicate things to justify our salaries.

Danny: You know, Florence, for a Victorian ghost, you’re surprisingly up to date. You don’t seem shocked by our technology, just disappointed in how we use it.

Florence: I am rarely shocked, Danny. Human nature doesn’t change. You have better tools, but the same blindness. You have miracle drugs, but you put patients in rooms that make them sick. You have iPhones, but you are lonelier than a shepherd on a hill. Progress is not a straight line. It is a spiral. You are currently on a downward turn of the spiral regarding your environment. I am here to suggest you start climbing back up.

Danny: Before we go, I have to ask. The “Fantastic Guest” segment usually ends with a fun question. If you weren’t a nurse, and you weren’t a statistician, what would you have been?

Florence: A murder mystery novelist.

Danny: Really?

Florence: I spent my life looking at clues—symptoms, data, environments—to find the killer. Sometimes the killer was a germ. Sometimes it was a corrupt general. Sometimes it was a bad architect. I think I would have given Agatha Christie a run for her money.

Danny: Death on the Nile, written by Florence Nightingale. I’d read that.

Florence: It would have been much more accurate regarding the poisons. And the detective would have washed his hands.

Danny: Florence, thank you. You’ve shed a lot of light—lamp or no lamp—on our topic.

Florence: You are welcome. Now, do something about the ventilation in this studio. It’s stuffy. I can feel my cognitive function declining by the second.

Danny: I’ll get the AC checked right away.

Florence: AC is recycled air! Open a window!

Danny: We’re in a basement!

Florence: Then move the studio! Good day, Danny.

Danny: Good day, Florence.

0 Comments