There is a strange cognitive dissonance that happens when we walk into a movie theater. Outside, on the sidewalk, we might be the kind of people who complain about wealth inequality. We might look at the skyrocketing net worth of tech moguls and wonder why one person needs enough money to buy a small country while the rest of us are budgeting for groceries. We might even nod along to arguments that billionaires shouldn’t exist, that no one earns a billion dollars without exploiting someone or breaking something.

Then, we buy our ticket, grab our popcorn, and sit in the dark for two hours to cheer for a billionaire who uses his massive, inherited fortune to beat up poor people.

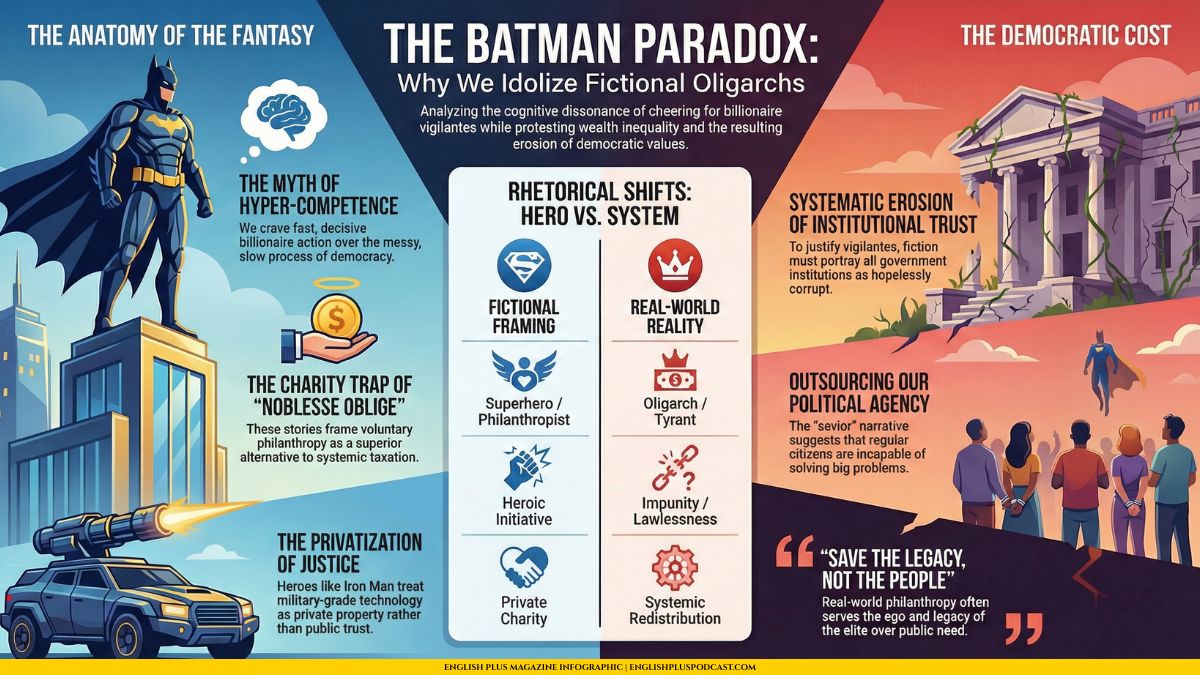

This is the Batman Paradox. And it’s not just Batman; it’s Iron Man, it’s Green Arrow, it’s a whole pantheon of fictional heroes who are essentially oligarchs. They are wealthy elites who operate completely outside the law, using private technology and military-grade weaponry to enforce their personal version of justice. In the real world, if a CEO built a fusion reactor in his basement and started flying around shooting lasers at criminals without a warrant, we would call him a dangerous warlord. In fiction, we call him a superhero.

Why is this archetype so appealing? Why do we protest against the 1% in the streets but idolize them on the screen? It isn’t just about cool gadgets or explosions. It goes much deeper, tapping into our anxieties about democracy, our frustration with bureaucracy, and a lingering, dangerous fantasy about the “Benevolent Dictator.”

The “Benevolent Dictator” Fantasy

Democracy is hard. It is messy, slow, and often incredibly boring. It involves committees, town halls, compromises, and the frustrating reality that you rarely get exactly what you want. Democracy requires us to accept that change takes time and that institutions, no matter how flawed, are the only way to govern a complex society fairly.

But the human brain doesn’t really like “slow and complex.” We like “fast and decisive.”

The Myth of Competence

This is where the billionaire superhero comes in. They represent the ultimate fantasy of competence. Bruce Wayne doesn’t have to wait for a city council vote to fix the Batmobile. Tony Stark doesn’t need to file an environmental impact statement before building a new suit. They just do it. They have the resources to bypass the gridlock of society and the will to act immediately.

We find this incredibly soothing. In a world where we feel powerless against massive systemic issues—climate change, crime, corruption—the idea of a single, hyper-competent individual who can fix everything with a checkbook and a punch is intoxicating. It relieves us of the burden of collective action. We don’t have to organize, vote, or protest if we can just wait for the guy in the cape to save us.

This is the core of the “Benevolent Dictator” myth: the belief that autocracy isn’t bad in itself, it’s just that we haven’t found the right autocrat yet. We tell ourselves that if we had that kind of money and power, we would use it for good. We would be the good billionaire. And so, we project that fantasy onto these characters. We ignore the fact that in reality, absolute power rarely creates benevolence; it usually creates tyranny. But in the safe confines of a comic book movie, we are allowed to indulge in the wish that a King—a good, kind, violent King—will come and clean up the mess.

Outsourcing Our Salvation

There is a psychological comfort in outsourcing our agency. When we watch these movies, we aren’t identifying with the citizens of Gotham who are terrified and helpless; we are identifying with the savior. But the narrative structure actually reinforces our helplessness. The police can’t stop the Joker. The mayor can’t stop the Joker. The voters certainly can’t stop the Joker. Only the billionaire can.

This creates a subtle cultural conditioning. It suggests that “regular” people are incapable of solving big problems. It implies that solutions must come from above, from the exceptional few who have the resources and the intellect to guide the sheep. It is a profoundly anti-democratic message wrapped in a shiny, entertaining package. It tells us that our role is to be rescued, not to be the rescuers.

Philanthropy vs. Taxation

If you look closely at the economics of superhero universes, you start to see a very specific political worldview. In these stories, money is a superpower, but only when it is spent voluntarily.

The Charity Trap

Bruce Wayne is often shown attending galas, writing massive checks to orphanages, and funding hospitals. Tony Stark funds scholarships. This is framed as the ultimate moral good. And don’t get me wrong, charity is great. But in the context of these stories, philanthropy is presented as a superior alternative to systemic change.

The message is clear: The rich should help people, but they should do it on their own terms, at their own discretion. It validates the idea of “Noblesse Oblige”—the obligation of the nobility to be generous to the peasants. This is a feudal concept, not a democratic one.

In a democracy, we ostensibly believe that resources should be distributed through taxation and public spending, decided upon by the people. But in superhero movies, taxation is almost never mentioned, and when the government tries to get involved with the hero’s money or tech, it is depicted as theft or overreach. Remember in Iron Man 2 when the US government wants Stark’s tech? The government is the villain. Stark, the private individual with a weapon of mass destruction, is the hero for refusing to hand it over.

Taxation as Theft (in fiction)

This reinforces a very specific libertarian fantasy: that the private sector is efficient and moral, while the public sector is greedy and incompetent. By cheering for Stark to keep his tech, we are cheering for the privatization of national security. We are cheering for the idea that a single individual has the right to decide how powerful technology is used, simply because he invented it (or paid for it).

It subtly trains us to view taxation as an infringement on greatness. If the government taxed Bruce Wayne properly, maybe Gotham could afford a better police force, better mental health services for all those Arkham inmates, and better street lighting. Maybe they wouldn’t need Batman. But that’s a boring story. A story about a well-funded municipal mental health clinic doesn’t sell tickets. A story about a billionaire jumping off a roof does. So, we accept the narrative that the best way to solve social problems is for the rich to throw scraps from their table, rather than for the table to be reset.

The Distrust of Institutions

To justify the existence of a vigilante, the system must be broken. If the police were competent, Batman would just be a weirdo in a costume interfering with an investigation. If the government were honest, Iron Man would be a dangerous rogue agent.

Incompetent Police and Corrupt Governments

So, fiction writers have to stack the deck. In Gotham City, the police are either hopelessly corrupt or breathtakingly incompetent. Commissioner Gordon is usually the only honest cop in the entire city, which is statistically impossible but narratively necessary. The politicians are always taking bribes from the mob. The judges are always letting criminals go on technicalities.

This creates a universe where “The System” is the enemy. It validates the cynic’s view that government is useless. It tells the audience, “See? You can’t trust the law. The law protects the bad guys. True justice comes from outside the law.”

The Vigilante Solution

This is where it gets dangerous. When we constantly consume media that portrays institutions as failures, it erodes our faith in real-world institutions. We start to believe that “red tape” (which is often just due process and civil rights) is an obstacle to justice. We start to crave the vigilante solution.

We see this spilling over into real-world discourse. When people cheer for extrajudicial punishments, or when they support leaders who promise to “smash the system” and ignore the courts, they are channeling that Batman energy. They want the quick fix. They want the strongman who ignores the rules because “he knows what needs to be done.”

But in reality, due process exists for a reason. “Technicalities” are often rights designed to protect the innocent. A vigilante doesn’t have a body camera. A vigilante doesn’t have an oversight board. If Batman beats up the wrong guy, who do you complain to? Alfred?

The superhero genre relies on the premise that the hero is infallible. We know Batman punched the right guy because the movie showed us he was the bad guy. But in the real world, vigilantes make mistakes. They have biases. They lack context. By idolizing the fictional version, we risk becoming tolerant of the real-world version, which is far less noble and far more dangerous.

The Hero We Deserve?

So, should we stop watching superhero movies? Of course not. They are fun, they are emotional, and they allow us to escape a complex world for a few hours. There is nothing wrong with enjoying the fantasy of a billionaire savior.

But we need to recognize it as a fantasy. We need to be critical of the worldview it smuggles in. We need to remember that in the real world, billionaires are not Tony Stark. They are not building suits to save the universe; they are building yachts to sail the Mediterranean. In the real world, a private citizen operating outside the law is not a hero; they are a threat.

The Batman Paradox is a reflection of our own impatience with democracy. It highlights our desire for easy answers and powerful saviors. But true heroism isn’t about one rich guy fixing everything. True heroism is the boring, slow work of building a society that doesn’t need a Batman in the first place. It’s about funding the schools, fixing the potholes, and ensuring that justice isn’t a privilege of the wealthy, but a right for everyone.

We can love the Bat, but we shouldn’t want to live in Gotham. And we certainly shouldn’t wait for a Bruce Wayne to save us. We have to save ourselves, and unfortunately, that doesn’t come with a cool cape. It comes with voting, organizing, and the hard work of being a citizen.

Focus on Language

Let’s shift gears and talk about the language we used in this article. One of the best things about analyzing pop culture through a political lens is that it gives us access to some incredibly sophisticated vocabulary that describes power, society, and human psychology. We aren’t just talking about “good guys vs. bad guys” anymore; we are talking about systems.

I want to highlight about ten specific words and phrases we used, break them down, and show you how to use them to sound more articulate in your daily life.

First, let’s look at the word “Oligarch.” We used this right in the title. An oligarch is a member of a small group of people who control a country or organization. Usually, we use this to talk about Russian billionaires or corrupt regimes. But using it to describe Batman or Iron Man is a powerful rhetorical move. It strips away the “hero” label and focuses on their wealth and power. In real life, you can use this to describe any industry dominated by a few rich players. “The tech industry is becoming an oligarchy; three companies control everything.” It implies that money equals power, and that power is concentrated.

Next is “Benevolent.” We talked about the “Benevolent Dictator.” Benevolent means kind, well-meaning, or charitable. It’s the opposite of malevolent. We often use it to describe someone in power who is actually nice. “He was a benevolent boss; he always gave us Fridays off.” But when we pair it with “Dictator,” it creates an oxymoron—a contradiction. It questions whether someone with absolute power can truly be kind.

Then we have “Impunity.” This is a crucial word when talking about justice. Impunity means exemption from punishment or freedom from the injurious consequences of an action. If you do something “with impunity,” it means you do it without fear of getting caught or punished. In the article, we implied superheroes operate with impunity. In real life, you might say, “People park in the bike lane with impunity because the police never write tickets.” It expresses frustration that the rules don’t apply to everyone.

Let’s talk about “Vigilante.” A vigilante is a member of a self-appointed group of citizens who undertake law enforcement in their community without legal authority. Batman is the textbook definition. But in real life, being a vigilante is usually seen as dangerous. You might use this metaphorically at work. “We can’t have vigilante coding; everyone needs to follow the proper protocols and get their code reviewed.” It means going rogue, even if you think you’re helping.

We also used the word “Archetype.” An archetype is a very typical example of a certain person or thing; a recurring symbol or motif in literature. The “hero,” the “villain,” the “wise old man”—these are archetypes. We called the billionaire hero an archetype. You can use this to analyze people or stories. “He fits the archetype of the absent-minded professor perfectly.” It’s a sophisticated way to say stereotype or model.

Here is a big one: “Redistribution.” This refers to the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others by means of a social mechanism such as taxation. We contrasted philanthropy with redistribution. Using this word shows you understand economics. “The debate isn’t just about growth; it’s about the redistribution of resources.” It sounds much more academic than just saying “sharing money.”

Let’s look at “Incompetence.” This means the inability to do something successfully. We talked about the myth of government incompetence. This is a great word for complaining professionally. Instead of saying “My team is stupid,” you say, “I am frustrated by the sheer incompetence of this department.” It attacks the skill level, not the person, although it’s still very harsh!

We used the phrase “Status Quo.” This is Latin for “the existing state of affairs.” Superheroes often fight to protect the status quo. In business or politics, this is used constantly. “We can’t just maintain the status quo; we need to innovate.” It refers to keeping things exactly as they are.

Another key term was “Nuance.” Nuance is a subtle difference in or shade of meaning, expression, or sound. We want to look at the nuance of the Batman story. In arguments, this is your best friend. “You’re ignoring the nuance of the situation; it’s not just black and white.” It makes you sound reasonable and deep.

Finally, let’s touch on “Agency.” In sociology and philosophy, agency is the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their own free choices. We said superhero movies strip citizens of their agency. If you feel like you have no control over your life, you lack agency. “I left that job because I felt I had no agency; I was just following orders.”

Speaking Section: The Power of Rhetorical Questions

Now, let’s take these words and put them into action. I want to talk about a specific speaking technique we used a lot in the article: The Rhetorical Question.

Did you notice how many questions I asked in the text? “Why is this archetype so appealing?” “Does this narrative train us to distrust democracy?”

I didn’t expect you to answer them out loud. I asked them to guide your thinking. In speaking, rhetorical questions are a weapon. They engage the listener. They force the listener to mentally agree with you before you’ve even made your point.

If I say, “Traffic is bad.” That’s a statement. It’s boring.

If I say, “Why do we accept that sitting in traffic for two hours is normal?” Now, I have your attention. I’m challenging the status quo.

Here is your challenge:

I want you to think of a problem in your life or your city. Maybe it’s the price of coffee, the noise, or a bad boss. I want you to formulate three rhetorical questions using three of the vocabulary words we just learned.

For example, if you are annoyed by your boss who micromanages but knows nothing, you might ask:

- “Why do we reward incompetence with high salaries?”

- “Does he think he can rule the office with impunity just because he’s the manager?”

- “Is this really leadership, or is it just the archetype of a bad boss?”

See how that works? It elevates your complaining into a philosophical critique! Try it out in front of a mirror or record yourself. It makes your English sound much more persuasive and dramatic.

Critical Analysis: In Defense of the Caped Crusader

Okay, let’s take a breath. We have spent a lot of time deconstructing the superhero myth, calling it anti-democratic, elitist, and essentially a propaganda tool for oligarchs. And while those arguments are valid, if we stop there, we are being intellectually lazy. We are ignoring the other side of the coin. To be truly critical thinkers, we have to play the devil’s advocate and defend the very thing we just critiqued.

Is it possible that the “Batman Paradox” isn’t actually a paradox, but a necessary function of storytelling?

First, let’s challenge the idea that these movies make us passive or anti-democratic. Literature has always focused on the “Exceptional Individual.” From Gilgamesh to Achilles to King Arthur, stories are rarely about a committee solving a problem through a series of votes. Why? Because that is boring. Drama requires conflict, and conflict requires a protagonist with the agency to act.

When we watch Batman, are we really thinking, “I wish a billionaire would save me”? Or are we engaging with a metaphor for personal responsibility? The core of the Spider-Man ethos—”With great power comes great responsibility”—is actually a deeply moral, pro-social message. It doesn’t matter if the power is money (Batman) or spider-webs (Peter Parker); the message is that if you can help, you must help. This encourages the viewer to look at their own capacity—however small—and ask, “What can I do?” It’s not necessarily about waiting for a savior; it’s about being inspired to be capable.

Furthermore, let’s look at the “Distrust of Institutions” argument. The article claims that portraying the government as incompetent is dangerous. But isn’t it also… realistic? Art reflects life. If Gotham’s police are corrupt, it’s because the writers are observing the real world where corruption exists. To demand that fiction always portray the government as effective and just would be its own form of propaganda—state propaganda.

In fact, the “Vigilante” narrative can be seen as a crucial check on power. When the system fails—when the law protects the rich or the corrupt—the vigilante archetype represents the moral conscience of society. It is the idea that Justice is separate from The Law. Sometimes, laws are unjust. Sometimes, institutions are oppressive. The hero who operates outside the law isn’t always an oligarch crushing the poor; sometimes they are the only force protecting the vulnerable from the state. Think of Robin Hood. He was a criminal. He was a vigilante. But he is a symbol of resistance against tyranny. Is Batman really so different just because he lives in a manor instead of a forest?

Finally, let’s touch on the “Benevolent Dictator” fantasy. Yes, in reality, it is dangerous. But in fiction, it serves a psychological need: the need for order in a chaotic world. We live in a time of massive uncertainty. We don’t know if the planet will be habitable in 50 years. We don’t know if the economy will collapse. The Superhero movie is a modern fairy tale. It provides a temporary resolution to unresolvable anxieties. To strip that away, to demand that our escapism be perfectly aligned with democratic theory, is to deny the human need for myth.

Maybe the problem isn’t the movies. Maybe the problem is that we have lost the ability to distinguish between myth and reality. We can enjoy the myth of the Benevolent King on Saturday night, and still vote for the boring, bureaucratic City Council on Tuesday morning. The human mind is capable of holding those two conflicting ideas at once. Isn’t it?

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to get you thinking and debating. I want you to take these to the comments section, discuss them with friends, or just journal about them.

Is “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” actually a dangerous idea?

We usually accept this as a good moral. But does it imply that only those with power matter? Does it suggest that if you don’t have “great power,” you don’t have responsibility? Discuss the difference between the responsibility of the elite vs. the responsibility of the common citizen.

If Batman existed in the real world, would you support him or want him arrested?

Move past the “cool factor.” Imagine a masked man is breaking bones in your neighborhood tonight. He says he’s targeting criminals, but he has no oversight. Do you feel safer? Or do you feel like you’re living in a war zone? Where is the line between a hero and a terrorist?

Can a billionaire ever truly be a “man of the people”?

We see politicians and fictional characters try to bridge this gap. But is the life experience of an oligarch so fundamentally different that they cannot possibly understand or represent the needs of the working class? Is empathy enough to bridge the wealth gap?

Does fiction shape our politics, or does politics shape our fiction?

Do we love Batman because we are already frustrated with democracy? Or are we frustrated with democracy because we grew up watching Batman? Which came first?

Is there a way to write a superhero story that respects democracy?

What would that look like? Would Iron Man have to testify before Congress every time he wants to launch a missile? Would that destroy the genre? Try to brainstorm a plot where the “system” works and the hero is still cool.

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Steel King

Danny: Welcome back to the show. We’ve been discussing the “Batman Paradox”—our cultural obsession with the idea that a billionaire operating outside the law is the best person to save us. We’ve talked about the fantasy, but I wanted to talk to the reality. I wanted to talk to a man who actually lived the Bruce Wayne life—minus the cape, but definitely with the massive fortune and the questionable use of private force. He is the man who built half the libraries in America and broke half the unions. Please welcome the author of The Gospel of Wealth, Mr. Andrew Carnegie. Mr. Carnegie, welcome.

Carnegie: Thank you, Danny. Although I must say, your studio is remarkably… small. Efficient, I suppose. I appreciate efficiency.

Danny: We operate on a budget here, Andrew. We don’t have “Steel Trust” money. Now, I brought you here because you are arguably the patron saint of the “Benevolent Billionaire.” You famously said that the man who dies rich dies disgraced. You gave away 90% of your fortune. You are basically the argument for Batman: that if we let men get obscenely rich, they will save society.

Carnegie: “Save” is a melodramatic word. I prefer “elevate.” You see, Danny, the problem with your premise—this “Batman” fellow—is that you focus on the violence. I focused on the intellect. I didn’t run around the streets punching pickpockets. That is a waste of a superior mind. I built libraries. I built universities. I built peace palaces. I didn’t fight crime; I fought ignorance. Ignorance is the parent of crime. If your Batman truly wanted to clean up his city, he would stop buying tanks and start funding reading rooms.

Danny: Fair point. But let’s stick to the core philosophy. In our article, we argue that relying on a billionaire’s charity is anti-democratic. It assumes that you know how to spend that money better than the public does through taxation. Isn’t that arrogant? Why should you get to decide that a town needs a library? Maybe they needed a hospital. Maybe they needed better wages. But because you’re the guy with the checkbook, you become the King.

Carnegie: And who should decide? The mob? The corrupt city councilman who lines his pockets with the road-paving budget? You speak of “Democracy” as if it is a magical engine of wisdom. It is not. It is a necessary mechanism for order, but it is rarely a mechanism for greatness. Look at history, Danny. Great things—universities, museums, concert halls—are rarely built by committees. They are built by men of vision who have the capital to execute that vision.

Danny: So you admit it. You believe the wealthy are a superior class of administrators.

Carnegie: I believe in the survival of the fittest. If a man has accumulated a massive fortune—honestly, through industry and innovation—he has proven he has a talent for organization. He has proven he understands systems. Why would you take that money out of the hands of the proven genius and give it to a bureaucrat who has never run a lemonade stand? It is wasteful. I regarded my wealth not as my own, but as a trust fund for the community. I was merely the trustee. I administered it because I could make a dollar go further than the government could.

Danny: That is the “Benevolent Dictator” fantasy right there! “I am the genius, so I should rule.” But here is the catch, Andrew. You built those libraries, sure. But you also slashed wages. You broke unions. You hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency—a private army—to shoot at workers during the Homestead Strike. You weren’t just a trustee; you were a tyrant. Batman beats up the Joker; you beat up your own employees.

Carnegie: The Homestead affair was… regrettable. I was in Scotland at the time, I will remind you.

Danny: Oh, the “I was on vacation” defense. Classic. But the system was yours. You created a system where your will was law. If the workers disagreed with your “vision,” you didn’t debate them democratically. You used force. This is the dark side of the superhero myth. When the “Good Billionaire” decides that he knows what is right, anyone who disagrees becomes a villain. To you, a union organizer asking for a raise was just as dangerous as the Joker.

Carnegie: You simplify a complex industrial reality. But let us look at the result. Yes, there was strife. Yes, there was pain. But look at America! We built the steel that holds up your skyscrapers. We built the rails that connect your coasts. And with the profits, I built the institutions that educated your grandfather. You judge the process; I judge the outcome. You want a world where everyone is equal and mediocre. I accepted a world where some were masters and some were not, provided the masters returned their surplus to the common good.

Danny: “Returned the surplus.” That’s a nice way of saying “giving back a fraction of what you took.” But let’s pivot to the modern day. You’d hate Bruce Wayne, wouldn’t you? Not because he’s a vigilante, but because he’s an heir.

Carnegie: Inherited wealth is a cancer. It breeds idleness. It breeds stupidity. This Bruce Wayne… he did not earn his fortune?

Danny: No. His parents died. He inherited the company.

Carnegie: Then he is a leech. A well-dressed leech, perhaps, but a leech. To leave a fortune to a child is to hang a millstone around their neck. It deprives them of the joy of struggle. It deprives them of the necessity of work. I advocated for a 100% estate tax. Did you know that?

Danny: Wait, really? The biggest capitalist in history wanted a 100% death tax?

Carnegie: Absolutely. The community allowed me to make that money. The workers, the infrastructure, the protection of the state. When I die, that money should go back to the community to facilitate the rise of the next generation of talent. It should not go to creating a dynasty of soft-handed aristocrats who play dress-up in bat costumes. If this Batman wants to be a hero, he should give away his company to his employees and start from zero. Then I will be impressed.

Danny: That is a fascinating distinction. You like the “Self-Made Man,” but you hate the “Oligarchy of Blood.” But Andrew, look at the modern tech billionaires. They are self-made. Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg. They are the new Titans. Do you see yourself in them?

Carnegie: I see the accumulation, but I do not see the distribution. I see men building rockets to escape the earth. I see men building digital worlds to escape reality. Where are the libraries? Where are the peace palaces? They seem to be hoarding.

Danny: They would say they are “investing in the future.” Musk wants to go to Mars to save the species. Isn’t that the ultimate “Gospel of Wealth”? A singular vision to save humanity, funded by private capital because the government is too slow to do it?

Carnegie: Going to Mars… it is grand, I grant you. It captures the imagination. But tell me, Danny, are there still hungry people in the shadow of his rocket launchpad?

Danny: Plenty.

Carnegie: Then he has failed the first duty of the trustee. You must elevate the man on the ground before you can elevate the man to the stars. This is the danger of the “Visionary” archetype you wrote about. The Visionary becomes so obsessed with the horizon that he tramples the flowers at his feet. I was guilty of this, perhaps. I looked at the “Future of Steel” and ignored the “Present of the Worker.” It is a dangerous blindness.

Danny: You’re getting introspective on me, Andrew. Are you saying you regret the Homestead Strike?

Carnegie: I am dead, Danny. Regret is the only thing I have left to do. I look back and I wonder… if I had paid them more, would they have needed the libraries?

Danny: That is the quote of the century. “If I had paid them more, would they have needed the libraries?” That is exactly the point of our article! If we tax the rich and pay fair wages, we don’t need your philanthropy. We don’t need you to be Batman. We can just be… citizens.

Carnegie: But will you? That is the question. You say, “Tax the rich, and we will build paradise.” But I look at your governments. I look at your trillions of dollars in public debt. I look at your bridges falling down. You tax, yes. But do you build? Or do you just consume?

Danny: We try. But it’s hard when the rich hide their money in offshore accounts.

Carnegie: Ah, “Offshore.” A coward’s trick. I made my money in America; I kept it in America. If these modern billionaires are hiding their gold, they are not Titans. They are pirates. A Titan stands in the public square and says, “Look what I built.” A pirate buries his chest on an island. There is no dignity in being a pirate.

Danny: Let’s talk about the “Architecture of Intimidation” from our previous segment. You built massive things. Steel mills. Mansions. Did you want people to feel small?

Carnegie: I wanted them to feel awed. There is a difference. When you walk into a Carnegie Library—and I insisted they be beautiful, with high ceilings and stone columns—I didn’t want the coal miner’s son to feel small. I wanted him to feel worthy. I wanted him to enter a palace of learning and feel that he belonged there just as much as a prince. That is not intimidation; that is aspiration.

Danny: That’s a lovely sentiment. But let’s be real. You also wanted your name on the door. “Carnegie Hall.” “Carnegie Mellon.” It’s ego.

Carnegie: Of course it is ego! I am a human being, not a calculator. I wanted to be remembered. Is that a crime? You want to be remembered for this podcast. The Batman wants to be remembered as the savior of Gotham. Ambition is the fuel of progress. If you remove the ego, you remove the drive. Show me a man with no ego, and I will show you a man who is happy to sleep in the mud.

Danny: So, the “Batman Paradox” is unavoidable? We need the ego of the billionaire to drive progress, but that same ego makes them dangerous?

Carnegie: Precisely. It is a bargain you make with the devil. You want the steel? You want the library? You want the Joker behind bars? Then you must tolerate the Monster who delivers it. You cannot have the greatness of the lion without the danger of the teeth.

Danny: That’s a terrifying worldview, Andrew. It suggests democracy is just a nice facade we put over the reality of raw power.

Carnegie: Now you are beginning to understand the world. Democracy is the garden we play in. Power is the wall that surrounds it. And sometimes, you need a gardener who isn’t afraid to use a machete.

Danny: Or a Batarang.

Carnegie: A what?

Carnegie: Never mind. It’s a boomerang shaped like a bat.

Carnegie: That sounds incredibly inefficient.

Danny: It is. But it looks cool. Andrew, before we go, I have to ask about the “Distrust of Institutions.” You hated unions. You didn’t trust the government to spend your money. Do you think that attitude—that “I alone can fix it” attitude—is what poisons our trust in democracy today?

Carnegie: I think trust is earned. If your institutions were competent, men like me would not be necessary. If your police could stop the criminals, Batman would stay home. If your schools were perfect, I wouldn’t have had to build libraries. Do not blame the strong man for stepping in when the weak man fails. If you want to get rid of the “Oligarch Savior,” make your democracy worthy of saving itself.

Danny: Make democracy worthy. That’s a challenge.

Carnegie: It is the only challenge that matters. Until then, you will keep looking at the sky, waiting for a billionaire to save you. And let me tell you, Danny, from experience… we are not coming to save you. We are coming to save our own legacy. If you happen to benefit, that is just a happy accident.

Danny: And on that cheerful note, Andrew Carnegie, thank you for joining us.

Carnegie: The pleasure was mine. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go haunt Jeff Bezos. I have some thoughts on his interior decorating.

Danny: Please do. Folks, there you have it. The original Iron Man. He admits it: Philanthropy is about legacy, not just charity. And maybe, just maybe, if we stopped waiting for the “Great Men” to build our libraries and fight our battles, we might realize we have the bricks to do it ourselves.

0 Comments