We must begin by asking a question that lies at the very bedrock of our shared existence: Is the rot inevitable? When we look at the structures of power—our governments, our corporations, our institutions—we almost invariably see the cracks of corruption. We see the self-interest that seeps into the mortar, weakening the walls that were meant to protect us. It is easy to dismiss this as a modern failing, a symptom of late-stage capitalism or the decline of traditional values. But if we zoom out, if we look across the vast, sweeping panorama of human history, we see that the rot is not new. It is ancient. It is as old as the first time one human being stood above another and claimed the right to rule.

This leads us to a terrifying possibility. What if corruption is not a bug in the system, but a feature of the human condition? What if the very act of governing, the very existence of hierarchy, necessitates a compromise of the soul? To wrestle with this, we must summon two ghosts to the table. On one side, we have Plato, the idealist, the architect of the perfect city. On the other, we have Niccolò Machiavelli, the realist, the advisor to princes who knew that the world is not as it should be, but as it is.

Plato believed in the “Philosopher King.” In his Republic, he posited that the only way to have a just society is to have rulers who are immune to the temptations of power. These rulers would not own property; they would not have families in the traditional sense. They would be bred and trained from birth to love wisdom more than gold, to value the Good more than the self. For Plato, corruption was a failure of education and a failure of the soul. It was a deviation from the ideal. He believed that if we could just align the human soul with the cosmic order of justice, we could create a state that was incorruptible.

But then, Machiavelli enters the room, smiling that thin, cynical smile. He looks at Plato’s city and sees a fantasy. Machiavelli argues that if a ruler tries to be “good” in a world where so many are “not good,” he will bring about his own ruin. For Machiavelli, corruption—or at least, the willingness to do “evil” things—is not a failure; it is a tool. A Prince must know how to be a beast as well as a man. He must know when to lie, when to cheat, and when to be ruthless, because if he does not, someone else will, and the state will fall.

So, we are trapped between these two visions. Are we fallen angels who can be redeemed by a perfect system, as Plato hoped? Or are we clever apes who must use deception to survive in a chaotic jungle, as Machiavelli feared?

Let us consider Lord Acton’s famous dictum: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” We quote this often, but we rarely pause to unpack the metaphysical weight of it. Acton is not just saying that bad people seek power. He is saying that power itself is an active agent. It is a radioactive substance. To hold it is to be changed by it.

Why does power corrupt? From an existential standpoint, power removes the constraints of necessity. Most of us are “good” because we have to be. We are polite to our neighbors because we need them to watch our house when we are away. We follow the laws because we fear the punishment. But power removes the fear. When you are the one writing the laws, when you are the one commanding the police, the external guardrails of morality vanish. You are left alone with your own will. And the human will, untethered from consequence, is a terrifying thing. It expands. It hungers. It begins to view other human beings not as ends in themselves, as Kant would argue, but as means to an end.

This brings us to the uncomfortable question of the “Benevolent Dictator.” If we accept that democracy is messy, prone to gridlock, and susceptible to the slow, creeping corruption of special interests, is there an argument for the singular, strong leader? Is a benevolent dictatorship better than a corrupt democracy?

Plato might say yes, if the dictator is truly wise. A single vision, unclouded by the need to pander to the masses, can achieve great things. It can build cathedrals; it can lift a nation out of poverty; it can impose order on chaos. But here lies the paradox. To maintain that dictatorship, even a benevolent one, requires the machinery of oppression. You cannot have a dictator without a secret police. You cannot have a dictator without censorship. To do “good” for the whole, the dictator must do “evil” to the individual who dissents.

And what happens when the benevolent dictator dies? Or worse, what happens when the benevolence fades, and only the dictatorship remains? The structure that was built to save the people becomes the cage that imprisons them. Machiavelli would nod here. He would say that the Prince must appear benevolent, yes, for the people must love him (or at least not hate him), but he must never actually be bound by the moral constraints of benevolence if the state’s survival is at risk. The “virtue” of the Prince is not moral goodness; it is effectiveness. Virtù, as Machiavelli called it—ability, skill, energy.

This friction brings us to the Social Contract. Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke argued that we trade our natural freedom—the freedom of the savage in the woods—for civil freedom. We agree to obey the laws, and in return, the state agrees to protect our life, liberty, and property. It is a contract.

But what is the ontological status of a contract that one side has broken? If the state becomes corrupt—if the leaders steal from the treasury, if the police protect the powerful and prey on the weak, if the laws are spiderwebs that catch the flies but let the hawks break through—is the contract null and void?

From an ethical standpoint, if the ruler breaks the contract, the citizen is released from the obligation to obey. This is the philosophical justification for revolution. But revolution is a dangerous fire. To burn down the corrupt house is easy; to build a better one from the ashes is the work of centuries.

Perhaps the problem lies in our expectation of purity. We want our leaders to be saints, but the job requires them to be sinners. We want the sausage of legislation to be delicious, but we cannot bear to watch how it is made. Max Weber spoke of the “ETHIC of RESPONSIBILITY.” He argued that the politician cannot just follow the “ETHIC of ULTIMATE ENDS”—doing what is purely right regardless of the consequences. The politician must answer for the results of their actions. Sometimes, to achieve a good result—peace, stability, prosperity—a leader must make a morally compromised choice. They must dirty their hands so that the citizens can keep theirs clean.

Is corruption inevitable? Perhaps in the absolute sense, yes. As long as humans are finite beings with infinite desires, there will always be a gap between what we ought to do and what we want to do. That gap is where corruption lives.

But this does not mean we succumb to nihilism. It does not mean we accept the Machiavellian nightmare as the only reality. We are capable of transcendence. We are capable of designing systems that acknowledge our flaws without surrendering to them.

The answer may not lie in a perfect leader (Plato’s dream) or a ruthless one (Machiavelli’s strategy), but in a vigilant citizenry. The unexamined state is not worth living in. We must be the philosophers in the marketplace. We must constantly ask the “Why” and the “What for.” We must hold the tension between the ideal and the real, never letting go of the demand for justice, even while navigating the muddy waters of the possible.

In the end, corruption is a test. It is the friction against which the moral character of a civilization is polished. It asks us: What do you value? What are you willing to sacrifice? And can you build a city that is just, even when the bricks are made of flawed clay?

We look at the horizon, and we see the sun setting on the ideal city. But in the twilight, we must light the lantern of inquiry. We must keep walking. For the search for the good life, the just life, is not a destination. It is the path itself.

Let us venture deeper into this labyrinth of the human soul. We have touched upon the political, but what of the personal? For the corruption of the state is merely the corruption of the individual writ large. As Plato famously drew the analogy between the soul and the city-state, we must ask: What does the existence of corruption say about the nature of our own consciousness?

There is a concept in existential philosophy called “Bad Faith” (mauvaise foi), coined by Jean-Paul Sartre. It describes the phenomenon where a human being, under pressure from societal forces, adopts false values and disowns their innate freedom to act authentically. Corruption, at its core, is a supreme act of Bad Faith. The corrupt individual convinces themselves that they had “no choice.” “I had to take the bribe because everyone else does.” “I had to lie because the truth would destroy me.” They objectify themselves. They turn themselves from a free agent—a “Being-for-itself”—into a mere object, a cog in the machine—a “Being-in-itself.”

When a politician accepts a kickback, they are essentially saying, “My will is not my own; it belongs to the highest bidder.” They are abdicating their humanity. They are trading the infinite potential of their freedom for the finite comfort of material gain. This is a tragedy not just of ethics, but of ontology. It is a diminishing of being.

But let us consider the counter-argument, the darker whisper of the universe. Is corruption actually an expression of the “Will to Power,” as Nietzsche might suggest? If life is fundamentally a struggle for dominance, a chaotic clash of forces where the strong survive and the weak perish, then is “corruption” just a moral label we slap onto the successful exercise of power by those we dislike?

Nietzsche would warn us against “slave morality”—the morality of the weak who demonize the strong to make themselves feel superior. Is our hatred of the corrupt politician partly envy? Do we secretly admire the audacity of the man who bends the rules to his will? There is a seductive quality to the transgressor. The “Great Man” of history—Caesar, Napoleon, Alexander—was rarely “good” in the conventional sense. They were corrupt. They stole empires. They murdered rivals. And yet, we build statues of them. Why?

Because deep down, we fear chaos more than we fear corruption. We fear the void. We fear the state of nature where life is, as Hobbes put it, “nasty, brutish, and short.” We crave order. And historically, order has often been purchased with the currency of corruption. The local boss who runs the neighborhood might be a criminal, but he keeps the streets safe from other criminals. He provides a structure. He is the Leviathan.

This brings us back to the benevolent dictator. The philosopher Voltaire once said, “I would rather obey a fine lion, much stronger than myself, than two hundred rats of my own species.” The lion is the dictator. The rats are the squabbling, corrupt senators of a failing democracy. There is an aesthetic appeal to the lion. It represents unity, strength, and purpose.

But the danger of the lion is that it eats you.

The philosophical problem with dictatorship—even the benevolent kind—is that it infantilizes the citizen. It robs us of our moral agency. If the dictator makes all the choices, even if they are good choices, the people cease to be moral actors. They become children in a nursery. And a life without moral agency, without the burden of choice, is an incomplete life. It is a life without the possibility of true virtue. For virtue requires the freedom to choose vice. If you are forced to be good, are you truly good?

Let’s pivot to the Social Contract again. This is perhaps the most profound fiction we have ever invented. It is a myth, but a necessary one. We pretend that we all sat down under a tree at the dawn of time and signed a paper agreeing to follow the rules. We didn’t. We are born into the contract without our consent. We are thrown into the world—Geworfenheit, Heidegger called it.

So, when the leaders break the contract, the existential crisis is severe. It reveals the fragility of the myth. It shows us that the “State” is not a divine entity; it is just a group of people with guns and stamps. When the veil drops, and we see the Wizard of Oz is just a frantic old man pulling levers, we experience a vertigo. Anomie. Normlessness.

In that moment of realization, when we see the corruption nakedly, we have two choices. We can descend into cynicism, which is the lazy man’s philosophy. The cynic says, “It’s all broken, so nothing matters.” This is a retreat from the world.

Or, we can embrace the Absurd. Albert Camus taught us that the world is silent to our demands for meaning and justice. We want the world to be fair; the world is not fair. That conflict is the Absurd. But Camus did not tell us to give up. He told us to revolt. To create meaning in spite of the silence. To fight for justice even knowing that perfect justice is impossible.

Fighting corruption, then, becomes an act of rebellion against the entropy of the universe. It is Sisyphus pushing the boulder up the hill. We know the boulder will roll back down. We know another corrupt politician will rise to replace the one we just jailed. But we push the boulder anyway. Why? Because the act of pushing is what gives us dignity. The struggle itself is enough to fill a man’s heart.

We must also consider the role of transparency—not just as a policy, but as a metaphysical concept. Light is the traditional metaphor for truth and goodness. Darkness is the metaphor for evil and ignorance. Corruption thrives in the shadows. It requires secrecy to survive. It is a fungus that dies in direct sunlight.

Therefore, the philosophical antidote to corruption is Aletheia—the Greek word for truth, which literally means “un-concealment.” To live in truth is to live without concealment. It is to live transparently. This is incredibly difficult. It requires a vulnerability that terrifies us. But a society that values Aletheia over comfort, that values the painful exposure of the truth over the soothing balm of the lie, is a society that can withstand the rot.

But let us not be naive. The debate between Plato and Machiavelli will never be resolved because it represents the dual nature of humanity itself. We have the capacity for the Good (Plato’s Forms), and we have the instinct for survival (Machiavelli’s Prince). We are creatures of the sky and creatures of the mud.

Perhaps the goal is not to eliminate corruption entirely—which would require eliminating human desire—but to contain it. To build a system of “Checks and Balances” is a philosophical acknowledgement of our fallen nature. We divide power because we know that no single human can hold it without being burned. We create rivalries between branches of government because we know that ambition must be made to counteract ambition (as Madison wrote).

This is a humble philosophy. It admits defeat before the battle begins. It says, “We cannot be angels, so let us build a government for devils.” And in doing so, paradoxically, we create a space where angels might occasionally visit.

So, as we ponder the headlines, as we watch the mighty fall and the corrupt rise, let us not lose heart. Let us instead deepen our understanding. Let us see corruption not just as a crime, but as a question. A question that the universe poses to us every day: Who are you?

Are you a consumer of the world, taking what you can? Or are you a citizen of existence, contributing to the order of things?

The choice, as always, remains yours. And in that choice lies the only freedom we truly possess.

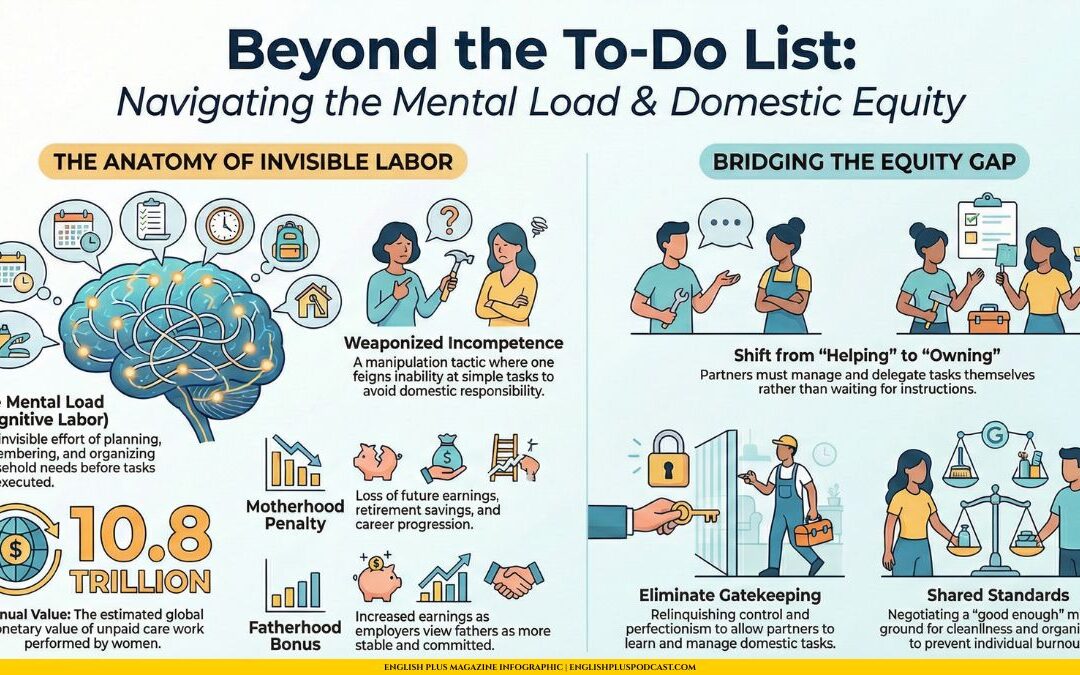

We must now turn our gaze to the mechanism of the soul that allows for the “slide.” We have spoken of the grand theories, but corruption is rarely a grand leap. It is a slow drift. The philosopher Hannah Arendt gave us the terrifying phrase “The Banality of Evil.” She was speaking of bureaucrats who sent millions to their deaths not out of sadistic malice, but out of a simple inability to think. They were just “doing their job.” They were following orders. They had ceased to be moral subjects and had become functions.

This banality is the soil in which corruption grows. It is the expense report padded by ten dollars. It is the blind eye turned to a colleague’s indiscretion because “he’s a good guy.” It is the gradual numbing of the conscience.

We must ask: What is the role of Empathy in this equation? Is corruption a failure of empathy? When a leader steals from the public purse to buy a yacht, they are abstracting the victim. They do not see the child who will go without a textbook. They do not see the patient who will die because the hospital lacks equipment. To them, the money is just a number on a screen. It has no moral weight.

The philosopher Levinas argued that ethics begins with the “Face of the Other.” When we look into the face of another human being, we are commanded: “Thou shalt not kill.” We are summoned to responsibility. Corruption is the act of turning away from the Face. It is an act of solipsism—the belief that only the self is real. The corrupt leader lives in a hall of mirrors, seeing only their own desires reflected back at them.

So, the antidote to the banality of evil is the “Radical Imagination.” We must imagine the lives of others. We must forcefully insert the reality of the victim into the equation of power. A just society is one where the imagination of the ruler is tethered to the suffering of the ruled.

Furthermore, let us consider the concept of Time. Corruption is often a theft from the future to pay for the present. It is “short-termism” weaponized. The politician who ignores climate change to please donors today is stealing the atmosphere from the children of tomorrow. The CEO who cuts safety corners to boost this quarter’s stock price is stealing the stability of the company from the employees of next year.

Heidegger spoke of “Being-towards-death.” He argued that our awareness of our own mortality is what gives life urgency and meaning. Perhaps our leaders have forgotten they are going to die. The accumulation of vast wealth, the desperate grasping for power—it reeks of a denial of death. It is an attempt to build a monument that will outlast the decay of the flesh. But it is a futile attempt. As Shelley wrote in “Ozymandias,” the lone and level sands stretch far away. The statues fall. The empires crumble. The offshore accounts are forgotten.

If our leaders truly meditated on their mortality—if they practiced the Stoic art of Memento Mori—would they still be so corrupt? If you know you are dust, does it matter if you are dust with a golden toilet? Perhaps the ultimate cure for corruption is a philosophical confrontation with the finite nature of existence. You cannot take it with you. The only thing that survives is the legacy of your character.

Finally, we must touch upon the concept of Dharma or Tao. In Eastern philosophy, there is the idea of a cosmic order, a “Way” that things should be. When the ruler is in alignment with the Tao, the empire is at peace. When the ruler goes against the Tao—when they force, when they grasp, when they are corrupt—nature itself rebels. The rivers flood. The crops fail. This is a metaphorical way of saying that corruption creates dissonance in the system. It introduces friction.

A corrupt system requires immense energy to maintain. You have to pay the spies. You have to suppress the truth. You have to constantly manage the lies. It is exhausting. It is contrary to the flow of reality. A just system, ideally, is efficient. It flows like water. It follows the path of least resistance because it is aligned with the needs of the people and the truth of the situation.

So, is corruption inevitable?

Let us conclude with a synthesis. Corruption is inevitable as a potentiality within the human heart. The shadow is always there. But it is not inevitable as a destiny. We are not doomed to be corrupt. We are condemned to be free.

We are the bridge between the beast and the Overman. We are the rope stretched over the abyss. We will wobble. We will slip. Some of us will fall into the darkness of greed and power. But the project of civilization—the project of philosophy—is to keep walking across the rope. To correct our balance. To help each other when we stumble.

We build the Republic not because we are perfect, but because we are not. We write the laws not to constrain our freedom, but to enable it. We fight the corruption not because we will win once and for all, but because the fight itself defines who we are.

In the silence of your own mind, ask yourself: Which wolf are you feeding? The wolf of Acton, hungry for power? Or the wolf of Plato, hungry for truth?

The debate continues. The ink is never dry. And you, my friends, are holding the pen.

Danny Ballan (The Thinker)

Editor-in-Chief

English Plus Magazine

0 Comments