- The Day Common Sense Died

- The Speed Limit of the Cosmos

- Special Relativity: The Elasticity of “Now”

- General Relativity: The Happiest Thought

- The Energy of Existence

- Conclusion: The Universe is Not What it Seems

- Focus on Language: Vocabulary and Speaking

- Critical Analysis

- Let’s Discuss

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding

The Day Common Sense Died

You likely have a very specific relationship with time. It is that nagging voice in your head telling you that you are running late, or that rigid grid on your calendar that dictates your week. We treat time as the ultimate, unshakeable backdrop of our lives. We assume that a second is a second, whether you are sitting on your couch, flying in a jet, or floating in the void of space. We assume that “now” is a universal concept—that if you snap your fingers, it happens at the exact same moment for you as it does for a little green man in the Andromeda galaxy.

This feels intuitive. It feels safe. It is also completely, spectacularly wrong.

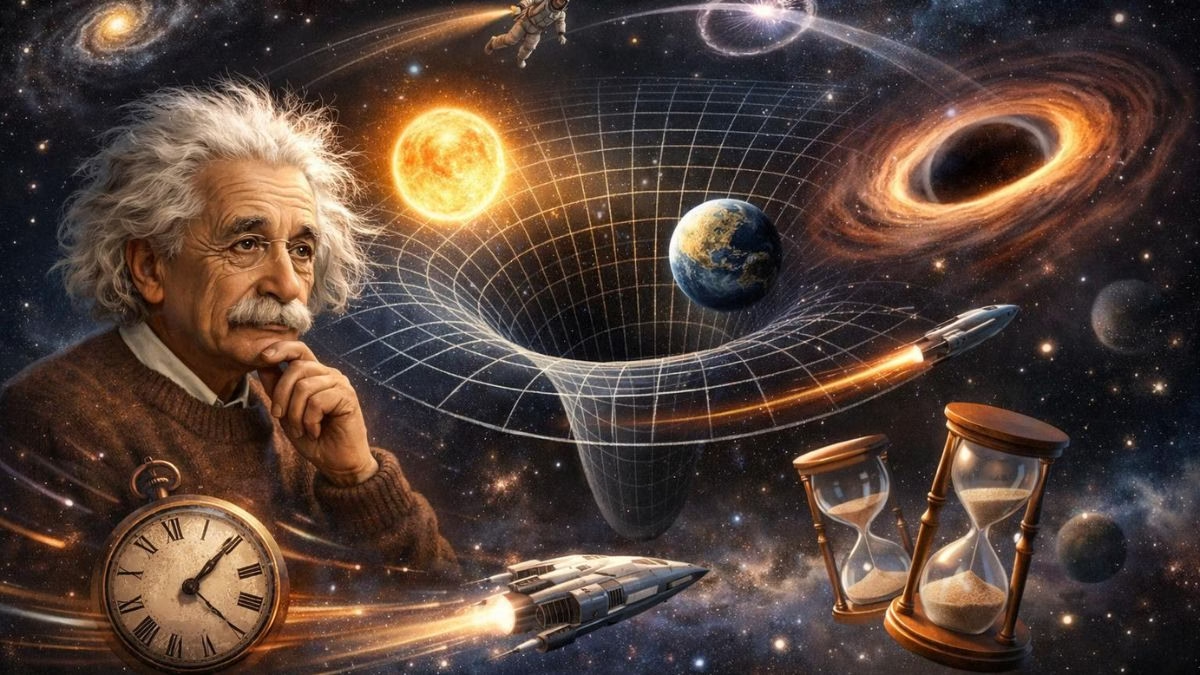

In 1905, a twenty-six-year-old patent clerk named Albert Einstein looked at the universe and realized that our common sense was lying to us. He stripped away the comforting illusion of absolute time and absolute space and replaced it with something far more fluid, more chaotic, and more beautiful. He gave us Relativity. And in doing so, he didn’t just change physics; he changed the philosophical bedrock of reality itself.

To understand relativity is to accept that your personal experience is just that—personal. There is no “view from nowhere.” There is only your frame of reference. The universe, it turns out, is not a stage where events play out against a static background. The stage itself is warping, stretching, and twisting along with the actors.

The Speed Limit of the Cosmos

Before we can talk about warping time, we have to talk about light. Before Einstein, we thought speed was additive. If you are on a train moving at 50 miles per hour and you throw a baseball forward at 50 miles per hour, the person on the ground sees that ball moving at 100 miles per hour. Simple math. First grade stuff.

Einstein realized that light refuses to play by these rules. If you are on a spaceship moving at half the speed of light and you turn on a headlight, that beam of light doesn’t travel at 1.5 times the speed of light. It travels at c—the speed of light (approx. 186,000 miles per second). And if you are standing still watching that ship? You also see the beam traveling at c.

This is the hinge upon which the entire universe turns. The speed of light is constant for all observers, regardless of their motion. But wait. Speed is just distance divided by time. If the speed of light must stay the same, but you are rushing towards it or away from it, then something else has to give. The math demands a sacrifice. And the sacrifice is time and space.

In order for the speed of light to remain constant, time itself must slow down for the moving observer, and space itself must shrink. This isn’t a mechanical trick or a measurement error. It is a fundamental property of existence.

Special Relativity: The Elasticity of “Now”

The Death of Simultaneity

Let’s get into the weird stuff. Imagine you are standing on a train platform. A train whizzes by at a significant fraction of the speed of light. (Just go with it; it’s a very fast train). In the exact center of the train car, a light bulb flashes.

For the passenger on the train, the light hits the front wall and the back wall at the exact same time. Why wouldn’t it? They are equidistant from the bulb. But you, on the platform, see something different. You see the train moving forward. The back wall is rushing toward the light signal, while the front wall is running away from it. To you, the light hits the back wall first and the front wall second.

Who is right? The passenger who saw the events happen simultaneously, or you who saw them happen sequentially?

The answer is: you are both right. “Simultaneity” is not an absolute fact. It is relative to your state of motion. Two events can happen at the same time for one person and at different times for another, and neither person is hallucinating. This shatters the idea of a universal “now.” The universe does not tick-tock in unison. Every object carries its own clock, and that clock beats to the rhythm of its own motion.

The Twin Paradox and Time Dilation

This leads us to the most famous thought experiment in history: The Twin Paradox. Take two identical twins. One stays on Earth. The other hops in a spaceship and blasts off to a distant star at 90% of the speed of light.

For the traveling twin, the journey might feel like a few years. They eat, sleep, and read books at a normal pace. Their biological clock ticks away normally. But when they return to Earth, they find a shock. Their stay-at-home sibling is now an old person, perhaps even long dead, while the traveler has barely aged.

This is Time Dilation. The faster you move through space, the slower you move through time. It implies that we are always traveling through spacetime at a constant velocity. If you use all your “speed” to travel through space (by moving at light speed), you have no speed left for time. You become timeless. Photons, which travel at light speed, do not experience time. For a photon, the moment it is created in a star and the moment it hits your retina a billion years later are the exact same moment.

General Relativity: The Happiest Thought

Special Relativity (1905) was about speed. But it ignored a massive, nagging problem: Gravity. Isaac Newton had given us a great description of gravity—apples falling, planets orbiting—but he never explained how it worked. He just assumed there was an invisible tether connecting the Earth and the Moon.

Einstein wasn’t satisfied with invisible tethers. He struggled for ten years, sweating over complex tensor calculus, until he had what he later called “the happiest thought of my life.”

Imagine a man falling off a roof. (I know, Einstein had a dark sense of humor, but stick with the physics). While that man is falling, he does not feel gravity. If he pulls a coin out of his pocket and lets go, it floats next to him. He is weightless. Einstein realized that acceleration and gravity are indistinguishable. Being in a closed room sitting on Earth feels exactly the same as being in a closed room on a rocket accelerating at 1g.

Warping the Fabric

From this equivalence principle, Einstein built General Relativity (1915). He threw out the idea of gravity as a “force” entirely. Instead, he proposed that mass tells space-time how to curve, and space-time tells mass how to move.

Imagine a trampoline. If you place a bowling ball in the center, the fabric sags. If you roll a marble nearby, it will curve around the bowling ball. It isn’t being “pulled” by the ball; it is simply following the straightest possible path along a curved surface.

Earth isn’t orbiting the Sun because the Sun is grabbing it. Earth is trying to move in a straight line, but the Sun has indented the fabric of the universe so deeply that the straight line becomes a circle. We are trapped in the Sun’s geometric dimple.

Black Holes and the Edge of Sanity

If you take this idea to its extreme, you get monsters. If you cram enough mass into a small enough volume, the curvature becomes infinite. The “trampoline” doesn’t just sag; it rips a hole in reality. This is a Black Hole.

Near a black hole, the warping of time becomes extreme. If you stood near the event horizon of a black hole while I watched from a safe distance, I would see you slow down. Your movements would become sluggish. Your voice would deepen. Eventually, you would appear to freeze entirely, fading into the darkness, frozen in time forever. But for you, looking at your watch, time would pass normally… until you crossed the horizon and were crushed into spaghetti.

The Energy of Existence

We cannot leave this discussion without mentioning the celebrity equation: $E=mc^2$. This popped out of Special Relativity, and it connects the two main characters of the physical world: Mass (matter) and Energy.

Before Einstein, we thought these were separate buckets. You had matter (rocks, planets, sandwiches) and you had energy (light, heat, motion). Einstein showed they are the same thing, just in different states. Mass is frozen energy. Energy is liberated mass. The “c squared” is a huge conversion factor, which explains why a tiny amount of uranium can flatten a city.

This means that you, sitting there reading this, are a dense bundle of potential energy. The atoms in your body contain enough latent power to fuel a civilization, if only we knew how to unlock it without exploding. It adds a layer of profundity to our existence; we are not just made of “stuff.” We are made of light that has slowed down and thickened.

Conclusion: The Universe is Not What it Seems

Why does this matter? Most of us will never fly near a black hole or travel at light speed. We live our lives in the “Newtonian bubble,” where speeds are slow and gravity is weak.

But Relativity matters because it humbles us. It strips away the anthropocentric arrogance that suggests our perception of reality is the reality. It reminds us that the universe is far stranger, more flexible, and more interconnected than our primate brains are wired to comprehend.

We are not independent observers watching the universe. We are threads woven into the fabric of spacetime itself. When we move, we warp the cosmos. When we stand still, we travel through time. We are participants in a four-dimensional dance that has been going on for 13.8 billion years. Einstein didn’t just give us a theory of gravity; he gave us a map to the architecture of eternity.

Focus on Language: Vocabulary and Speaking

Let’s pause for a moment. We have just traversed the galaxy, surfed on light beams, and fallen into black holes. That is a lot of heavy lifting for the brain. But to truly own these concepts—to be able to talk about them at a dinner party without sounding like you are reading from a textbook—you need the right tools. You need a vocabulary that is precise but also evocative.

We used some specific words in that article that do double duty. They describe physics, but they are also incredibly useful in everyday life. Let’s unpack them, not as definitions, but as weapons in your conversational arsenal.

First, let’s look at intuitive. We said relativity is not intuitive. Intuitive refers to something that you understand instantly, without conscious reasoning. It’s a gut feeling. “It is intuitive to pull your hand away from fire.” In real life, you often use this to describe design or people skills. “This app is so intuitive; I didn’t even need the manual.” Or the opposite, counterintuitive, which is a powerhouse word. Use this when something goes against common sense but is actually true. “It is counterintuitive, but to get the car out of the skid, you have to steer into it.”

Then we have the word dilate. In the article, we talked about time dilation—time stretching out. But you probably know this word from the eye doctor. When they put drops in your eyes, your pupils dilate (get wider). In conversation, you can use this metaphorically, though it is rarer. You might hear, “His eyes dilated with fear.” It suggests an expansion, a widening.

We threw around the word fabric. The “fabric of spacetime.” Fabric usually means cloth, the stuff your shirt is made of. But metaphorically, it refers to the underlying structure or framework of something complex. You can talk about the “social fabric” of a community. “The lies told by the politicians are tearing the fabric of our society apart.” It implies that society is woven together, and if you pull one thread, the whole thing might unravel.

Absolute and relative. These are the stars of the show. Absolute means universally valid, viewing something without relation to other things. “I have absolute confidence in you.” “That is an absolute lie.” Relative means considered in relation to something else. “The car is cheap, relatively speaking” (meaning compared to a Ferrari, not a candy bar). In arguments, this distinction is gold. “Is stealing wrong?” “Absolutely.” “What if you are stealing bread to feed a starving child?” “Well, now it’s relative.”

Let’s talk about warp. To warp means to become bent or twisted out of shape. Wood warps if it gets wet. Spacetime warps near a star. You can use this to describe a person’s personality or view. “His judgment was warped by jealousy.” “That is a warped sense of humor.” It implies a distortion of the natural state.

Frame of reference. This is a physics term that has migrated beautifully into sociology and psychology. In physics, it’s the state of motion of the observer. In life, it is your background, your culture, your bias. “I don’t understand why he is so offended, but maybe I’m missing his frame of reference.” It is a sophisticated way of saying “point of view,” but it implies a structural limitation. You can’t see what you can’t see.

Constant. In the article, the speed of light is a constant. In math, a constant is a number that doesn’t change. In life, a constant is something—or someone—dependable. “In the chaos of my divorce, my sister was the one constant.” It means unchangeable, faithful, enduring.

Simultaneity. The quality of occurring at the same time. This is a bit of a mouthful, but it’s great for logistics. “We need to execute the launch of the website and the press release with simultaneity.” It sounds much sharper than “at the same time.”

Trajectory. We talked about the path of Earth or a marble. A trajectory is the path followed by a projectile flying or an object moving under the action of given forces. You can use this for careers or lives. “Based on his current grades, his career trajectory is looking very promising.” “The company is on a downward trajectory.”

And finally, paradox. A seemingly absurd or self-contradictory statement or proposition that when investigated or explained may prove to be well founded or true. The Twin Paradox. Life is full of them. “It is a paradox that the more you chase happiness, the harder it is to find.”

Now, let’s stop reading and start speaking. I want you to internalize these words. It is not enough to recognize them; you have to feel comfortable having them in your mouth.

The Speaking Challenge: Explain Like I’m Five (ELI5)

Here is your assignment. I want you to pretend you are explaining a complex situation to a five-year-old (or just a confused friend), but you have to use sophisticated vocabulary to do it. This forces your brain to bridge the gap between high-level language and simple concepts.

Pick a topic: Why do we have to follow rules?

Now, record yourself giving a 60-second answer. But you must use the words: Intuitive, Fabric, Absolute, and Consequence (or Trajectory).

It might sound like this:

“Well, buddy, I know it feels intuitive to just take the cookie when you want it. It feels natural. But imagine our family is like a blanket, a fabric woven together. If everyone just did what they wanted, the blanket would rip. We have some absolute rules, like ‘don’t hit,’ because if we break them, the trajectory of our day goes from happy to sad very fast.”

Do you see what happened there? You took a parenting moment and elevated it. You practiced linking abstract concepts (fabric, trajectory) to concrete reality (family, day).

Challenge 2: The Devil’s Advocate

Record yourself arguing against a popular opinion. For example: “Money buys happiness.” Use the words Relative and Context.

“Money buying happiness is relative. To a starving man, ten dollars is joy. To a billionaire, it is nothing. Without the context of need, the money has no emotional value.”

Practice this. Record it. Listen to it. Do you sound natural? Or do you sound like you are forcing the words? If you are forcing them, do it again. Fluency comes when the word feels like the only right choice for the sentence.

Critical Analysis

Now, let’s take off the storyteller hat and put on the “physicist with a grudge” hat. We have spent this whole article praising Einstein and his beautiful, elegant theory. But if we are being intellectually honest, we have to admit: Relativity is likely wrong.

Or, at the very least, it is incomplete.

The article paints a picture of a smooth, geometric universe. Spacetime is a fabric. It curves. It stretches. This works perfectly for big things—planets, stars, galaxies. But when you zoom in to the subatomic level—the world of Quantum Mechanics—Relativity falls apart.

In Quantum Mechanics, the universe is not smooth. It is “pixelated.” It is chaotic. Particles pop in and out of existence. They can be in two places at once. If you try to apply Einstein’s smooth geometry to the jagged chaos of the quantum world, the math explodes. You get “infinities” that make no sense. This is the Theory of Everything problem. We have two rulebooks for the universe (Relativity for the big, Quantum for the small), and they contradict each other. We completely glossed over this conflict in the main article because it complicates the narrative, but it is the single biggest open wound in modern physics.

Furthermore, we talked about gravity as if we understand it perfectly. We don’t. To make Relativity fit the observations of rotating galaxies, we had to invent Dark Matter and Dark Energy. These are invisible substances that make up 95% of the universe, yet we have never seen them or touched them. We basically invented “ghosts” to save Einstein’s equations. Is Relativity actually correct, or are we just adding “fudge factors” to make a broken theory work? It is a valid, critical question that the article conveniently side-stepped.

Finally, there is the philosophical horror of the Block Universe. If time is a dimension like space (as Relativity suggests), then the past, present, and future all exist simultaneously. The future is already written; we just haven’t walked there yet. This suggests that Free Will is an illusion. We are just sliding down a pre-built slide. The article ended on a poetic note about “weaving the fabric,” but it ignored the terrifying possibility that the fabric was woven long before we were born, and we are just patterns trapped in the weave.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to break your brain. I want you to take these into the comments section (or your own internal monologue) and wrestle with them.

1. If you could travel near a black hole and skip 100 years into the future, but you could never come back, would you do it?

This isn’t just about curiosity. It’s about attachment. What binds you to your current time? Is it people, or is it the culture? Would you choose to be an explorer if it meant becoming a ghost to everyone you love?

2. If “now” is relative, does the past still exist?

If an alien moving towards Earth sees our “future” as their “present,” does that mean our future has already happened? Discuss the idea of the “Block Universe”—is the future set in stone?

3. Why do we perceive time as flowing if physics says it’s just a dimension?

Space doesn’t “flow.” We can move left or right. Why can we only move “forward” in time? Is the flow of time an illusion created by our brains to make sense of entropy?

4. Does the fact that we need “Dark Matter” to make Einstein’s theory work mean the theory is wrong?

Compare this to the discovery of Neptune (math predicted it) vs. the “Ether” (a made-up substance that didn’t exist). Are we on the verge of a new revolution that will make Einstein look like Newton—correct but limited?

5. Is math invented or discovered?

Einstein used tensor calculus to describe the universe. Did the universe inevitably follow those rules, or did we just create a language that approximates the chaos? If we met aliens, would they have the same relativity?

0 Comments