- The Alphabet of Existence

- Reading the Library

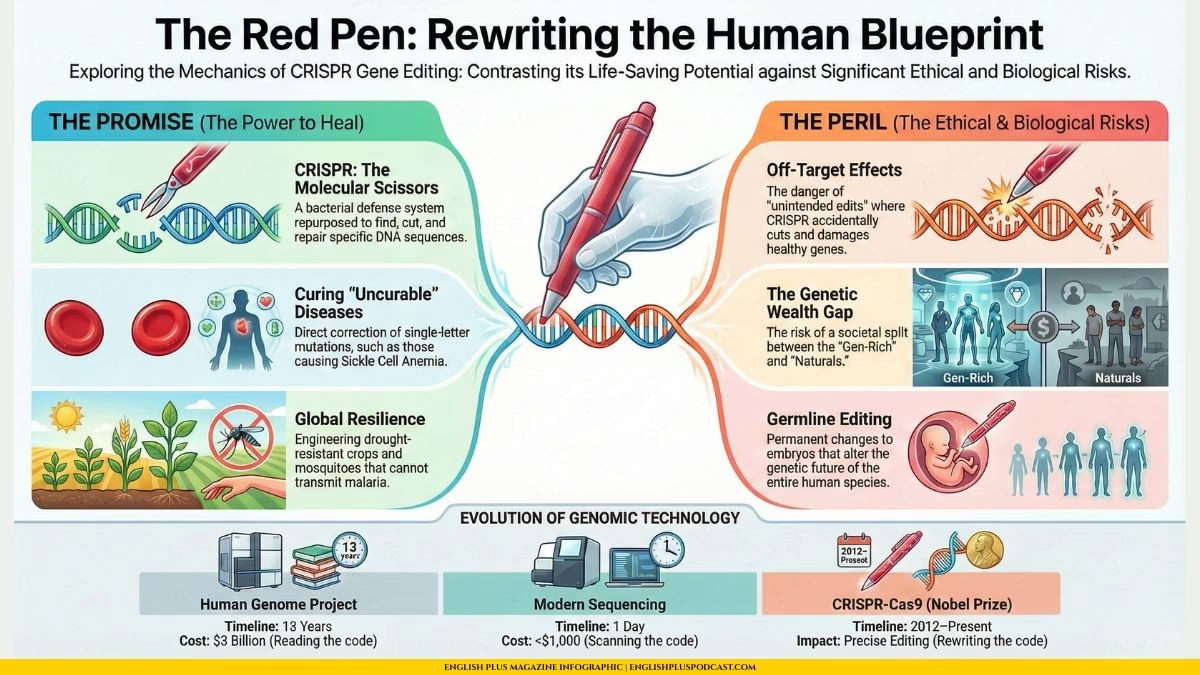

- Enter the Molecular Scissors

- The Promise: Deleting Disease

- The Peril: The Slippery Slope of “Better”

- The Wealth Gap of Genes

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis: The Devil’s Advocate

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Mother of Monsters

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

Imagine for a moment that you are a piece of IKEA furniture. I know, it’s not the most glamorous metaphor, but bear with me. You are a complex, self-assembling bookshelf that walks, talks, and occasionally forgets where it left its keys. Now, usually, when you buy a bookshelf, it comes with a manual. It’s a frustrating, paper-thin booklet with indecipherable diagrams and a little cartoon man who looks suspiciously happy about using an Allen wrench.

For millennia, humans have known that the manual existed. We knew that tall parents usually had tall children. We knew that if you bred a fast horse with another fast horse, you probably wouldn’t get a slow donkey. But we couldn’t find the book. We were just guessing at the instructions based on the finished product.

Then, about seventy years ago, we found the manual. We discovered DNA. And for the last few decades, we’ve been furiously trying to read it. It was expensive, slow, and full of words we didn’t understand. But recently, something fundamental changed. We didn’t just learn how to read the manual; we bought a red pen. We found a pair of molecular scissors. We discovered CRISPR. And now, for the first time in the four-billion-year history of life on Earth, the furniture has figured out how to rewrite its own instructions.

The Alphabet of Existence

Let’s strip this down to the studs. At the center of almost every cell in your body is a nucleus, and inside that nucleus is the instruction set for you. It’s called Deoxyribonucleic Acid, which is a mouthful, so we stick to DNA.

It is elegantly simple. The entire diversity of life on this planet—from the moss on a rock to the blue whale breaching in the Pacific, to you reading this article—is written in a language that has only four letters: A, C, G, and T. These are nucleotides (Adenine, Cytosine, Guanine, Thymine).

Think of it like binary code. Computers run the entire digital world using just zeros and ones. Biology runs the physical world using four letters. These letters are paired up on a twisting ladder—the famous Double Helix—and the order of these letters determines everything. If you spell the word one way, you get a banana. Spell it another way, and you get a bonobo. It is a humbling realization that the genetic difference between you and a chimpanzee is less than 2%, essentially a few typos in a very long book.

Reading the Library

For a long time, we were just staring at the cover of this book. Then came the Human Genome Project. Launching in 1990, this was the biological equivalent of the moon landing. The goal was to sequence—meaning, to read out loud—the entire 3 billion letters of the human genetic code.

It took thirteen years and cost nearly three billion dollars. Thirteen years to read one human book. It was a monumental achievement, but it wasn’t exactly practical for your average doctor’s visit.

But technology moves fast. Today, we can sequence a human genome in a day for less than a thousand dollars. We have moved from reading the code with a magnifying glass to scanning it with high-speed lasers. We have built a map. We know where the gene for eye color lives. We know which spelling mistakes cause Cystic Fibrosis or Huntington’s disease. We have identified the “BRCA” mutations that predispose women to breast cancer.

But reading is passive. Reading tells you that you have a flat tire; it doesn’t hand you the jack. For decades, gene therapy was a clumsy, dangerous affair. We tried to jam new genes into cells using viruses, hoping they would stick in the right place. It was like trying to fix a typo in a dictionary by throwing a handful of alphabet soup at the page and hoping the letters landed in the right order.

We needed a word processor. We needed a cursor. We needed CRISPR.

Enter the Molecular Scissors

CRISPR sounds like a new brand of artisanal lettuce, but it stands for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.” Don’t worry, you don’t need to memorize that.

Here is the irony: We didn’t invent CRISPR. Bacteria did.

For billions of years, bacteria have been fighting a war against viruses. When a virus attacks a bacterium, it injects its own DNA to hijack the cell. If the bacterium survives, it wants to remember that attacker. So, it takes a tiny snippet of the virus’s DNA and files it away in its own genetic code—like a mugshot in a database. This database is the “CRISPR” part.

The next time that virus shows up, the bacterium checks the mugshot. If it finds a match, it deploys an enzyme called Cas9. Think of Cas9 as a pair of molecular scissors guided by a GPS. It hunts down the invading viral DNA and snips it. The virus is destroyed.

In 2012, scientists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier (who won the Nobel Prize for this) realized something profound: We could reprogram the GPS. We could give Cas9 a different mugshot. We could tell it to search for any sequence of DNA.

Suddenly, we had a tool that could scan the billions of letters in the human genome, find a specific typo, and cut it. And because cells naturally try to repair cuts, we could paste in a correct letter. We could edit the book of life with the precision of a copy editor.

The Promise: Deleting Disease

The implications are staggering. There are thousands of genetic diseases caused by a single wrong letter. Sickle Cell Anemia, for example, is a brutal disease caused by a single mutation in the gene for hemoglobin. The red blood cells become misshapen, causing pain and organ damage.

With CRISPR, we are already seeing cures. Doctors extract stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow, use CRISPR to edit the error in a lab, and then infuse the corrected cells back into the patient. It is not science fiction; it is happening right now. People who were crippled by pain are now living normal lives.

But it goes beyond humans. We are editing crops to be drought-resistant or to produce more food on less land. We are editing mosquitoes so they cannot carry malaria, potentially saving hundreds of thousands of lives a year. Scientists are even talking about “de-extinction”—using CRISPR to splice Woolly Mammoth DNA into elephants to bring the giants back to the Arctic tundra.

The Peril: The Slippery Slope of “Better”

If this sounds too good to be true, that’s because we haven’t talked about the darker side yet. The same pen that corrects a typo can be used to write a whole new chapter.

Right now, most gene editing is “somatic.” This means we edit the cells of an adult patient. If we fix your lungs, you don’t pass that fix down to your children. The change dies with you.

But what if we edit an embryo? What if we edit the sperm or the egg? This is called “Germline Editing.” If you change the code here, that change is passed down to every generation that follows. You are altering the future of the human species.

In 2018, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui shocked the world by announcing he had created the first “CRISPR babies”—twin girls whose DNA had been edited to be resistant to HIV. The scientific community was horrified. Not because preventing HIV is bad, but because we crossed a line. We started designing humans.

This leads us to the “Gattaca” scenario. If we can edit out disease, can we edit in intelligence? Can we edit in height, or athletic ability, or blue eyes? Biology is messy, and intelligence isn’t controlled by one gene—it’s a symphony of thousands. But as we get better at reading the score, the temptation to conduct the orchestra will be overwhelming.

The Wealth Gap of Genes

Imagine a world where the rich can afford not just better schools and better nutrition, but better genes. A world where inequality isn’t just social, but biological. If CRISPR becomes a service you buy, we could see a split in the human species between the “Gen-Rich” and the “Naturals.”

We are standing on the precipice of the greatest technological shift in human history. Fire gave us the power to change our environment. Agriculture gave us the power to sustain civilization. The internet gave us the power to connect minds. But Genetics gives us the power to change the user itself.

We are holding the red pen. The question is no longer “Can we rewrite the story?” The question is, “Do we have the wisdom to write a happy ending?”

Focus on Language

Let’s take a magnifying glass to the language we used in this article. Writing about science requires a specific toolkit. You need to be precise, but if you are too academic, you lose the audience. The trick is to use Analogies and Metaphors.

I want to highlight ten key words and phrases we used, break them down, and show you how to use them to sound more articulate—whether you are talking about biology or just sound smart at a dinner party.

First, let’s look at “Blueprint.” We called DNA the “blueprint of life.” A blueprint is a design plan or technical drawing. Architects use them to build houses. In conversation, you can use this to describe any foundational plan. “We need a blueprint for this marketing strategy.” It implies a structured, detailed guide.

Next is “Nucleus.” In biology, it’s the center of the cell holding the DNA. But in general English, nucleus means the central and most important part of an object, movement, or group. “Steve was the nucleus of our friend group; without him, we drifted apart.” It implies the core that holds things together.

Then we have “Snippet.” We talked about bacteria taking a “snippet” of virus DNA. A snippet is a small piece or brief extract. You usually hear it regarding information or code. “I only heard a snippet of their conversation.” It suggests a fragment, not the whole picture.

Let’s talk about “Mutation.” Scientifically, this is a change in the DNA sequence. But we use it in general language to describe any significant alteration, often a weird one. “The movie was a strange mutation of comedy and horror.” It implies a change that creates something new and distinct.

A great phrase we used is “Precipice.” We said we are standing on the precipice of a technological shift. A precipice is a very steep rock face or cliff, typically a tall one. Figuratively, it means the verge of a dangerous or momentous situation. “The company is on the precipice of bankruptcy.” It adds a sense of drama and height.

We mentioned “Somatic.” This is a specific biological term referring to the body (distinct from the mind or the germline/reproductive cells). You might hear this in psychology, too—”Somatic symptoms” are physical symptoms caused by mental stress. It connects to the Greek word “Soma,” meaning body.

Then there is “Germline.” This refers to the sex cells (eggs and sperm) that pass genetic information to the next generation. In a broader sense, you can think of it as the “legacy” code. Editing the germline is controversial because it is permanent for all future generations.

Let’s look at “Ethical Quagmire.” We didn’t use the exact phrase “quagmire” in the text, but we described the situation as one. A quagmire is a soft boggy area of land that gives way underfoot—a swamp. Metaphorically, it is an awkward, complex, or hazardous situation. “The political debate turned into an ethical quagmire.” It implies you are stuck and every move is difficult.

We used the term “Hubris.” This is excessive pride or self-confidence. In Greek tragedy, hubris is what gets the hero killed by the gods. When we talk about “playing God” with genetics, we are talking about hubris. “It was sheer hubris to think we could control the market.”

Finally, “Resilience.” We talked about editing crops for drought resilience. Resilience is the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness. You want resilient crops, resilient children, and resilient software. “Her resilience in the face of failure was inspiring.”

Speaking Section: The Power of Analogy

Now, let’s move to the speaking lesson. The most powerful tool we used in the article was the Analogy. We compared DNA to a book, to binary code, to IKEA furniture.

Why do we do this? Because the human brain hates abstract concepts. It loves concrete images. If I say “The genome is a sequence of nucleotides,” you fall asleep. If I say “The genome is a recipe book,” you understand instantly.

The Challenge:

I want you to practice this. I want you to take a complex topic you know well (your job, a hobby, a sport) and explain it using an analogy involving food or construction.

- Example: “Writing code is like building a LEGO castle. You have tiny blocks (commands) that have to snap together perfectly. If you use the wrong block at the bottom, the whole tower falls over.”

Your Turn:

Take the concept of “Inflation” (economics).

Complete this sentence: “Inflation is like…”

Try to use the vocabulary words we learned. For example: “Inflation is like a mutation in the value of money…” or “It affects the blueprint of our budget…”

Speaking in analogies makes you a master communicator. It shows you understand the subject so well that you can translate it. Try it out in your next conversation!

Critical Analysis: The Devil’s Advocate

We have painted a picture of a brave new world where we cure cancer with a pair of molecular scissors. It is exciting. It is hopeful. But if we are being rigorous thinkers, we have to stop and ask: What could go wrong? And not just in a sci-fi movie way, but in a practical, biological way.

Let’s play Devil’s Advocate against the “Genetic Utopia.”

1. The “Off-Target” Effect

The article describes CRISPR as a “cursor” or a “copy editor.” This implies 100% precision. But biology is rarely 100% precise. CRISPR sometimes cuts the wrong place. These are called “off-target effects.” Imagine you want to fix a typo on page 50, but the scissors also accidentally cut a paragraph on page 100 that looks similar. If that paragraph on page 100 was the gene that suppresses tumors, you might have cured a blood disease but caused cancer. We are getting better at precision, but the risk of “unintended edits” is the ghost haunting every geneticist.

2. The Pleiotropy Problem

We tend to think of genes as “one gene, one trait.” There is a gene for blue eyes. A gene for height. But most genes are “Pleiotropic”—meaning one gene influences multiple, seemingly unrelated traits.

Let’s say we find a gene linked to intelligence and we decide to “boost” it in an embryo. Great, now the kid is a genius. But what if that same gene also regulates anxiety? Or immune response? We might create a generation of geniuses who are neurotic or immunocompromised. Evolution has spent millions of years balancing these trade-offs. Assuming we can pull one thread without unraveling the sweater is a dangerous form of hubris.

3. The Loss of Biodiversity

We talked about editing crops to be “better.” But “better” usually means “uniform.” If every banana is the exact same perfect, disease-resistant clone, the population becomes incredibly fragile. If a new disease comes along that figures out how to attack that specific clone, we lose all the bananas. Variation is nature’s insurance policy. By engineering perfection, we might be engineering fragility.

4. The Eugenic Shadow

We touched on the “Wealth Gap,” but let’s call it what it is: Eugenics. The 20th century saw horrific attempts to “improve” the human stock through forced sterilization and genocide. Those were state-sponsored programs. The new eugenics won’t be state-sponsored; it will be consumer-driven. It will be parents wanting the best for their kids. It’s harder to fight because it comes from a place of love, not hate. But the result is the same: the idea that some lives are biologically superior to others. Once we accept that premise, the moral foundation of “equality” begins to crack.

5. The Consent of the Unborn

When we do somatic editing (on an adult), the patient signs a consent form. When we do germline editing (on an embryo), who signs? That child, and all their descendants, are having their genetic code altered without a vote. We are making permanent decisions for people who do not exist yet. Is it ethical to burden a future child with our current definition of “perfection”? Fashion changes. Values change. A genetic modification made in 2024 might be seen as a deformity in 2124.

These arguments don’t mean we should stop. Curing Sickle Cell is a moral imperative. But they suggest we should move with extreme caution. We are walking into a room full of expensive crystal with a hammer in our hand, and we’ve only just learned how to swing it.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to spark a debate. These aren’t easy, and there are no right answers. Use these to dig deeper into the topic.

If you could edit your child to be immune to cancer, would you do it?

Most people say “yes” to health. But what if the package includes being 6 feet tall? Where do you draw the line between “therapy” (fixing) and “enhancement” (upgrading)?

Should the government regulate your DNA?

If I own my body, do I own my code? Should I be allowed to hack my own genes in my garage (Biohacking)? Or is the risk of creating a super-virus so high that the government needs total control?

Is “De-Extinction” a good use of resources?

Bringing back the Woolly Mammoth sounds cool. But shouldn’t we spend that money saving the elephants that are alive now? Is de-extinction just a vanity project for guilty humans?

How do we handle the “Genetic Olympics”?

If some athletes are genetically edited to have more red blood cells (endurance), is that cheating? Or is it just the new steroid? Do we need separate leagues for “Naturals” and “Edited”?

Does a disability need to be “fixed”?

The Deaf community often argues that deafness is a culture, not a disease to be cured. If we edit out deafness, are we destroying a culture? Who gets to define what a “defect” is?

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Mother of Monsters

Danny: Welcome back. We’ve been talking about CRISPR, gene editing, and the incredible, terrifying power to rewrite the blueprint of life. We’ve covered the science, the potential cures, and the ethical quagmire of “designer babies.” But to really understand the soul of this debate, I didn’t want a geneticist. I wanted a prophet. I wanted the woman who looked at the scientific ambition of the 19th century and saw a nightmare. She wrote the guidebook on what happens when humans try to take the reins of creation from nature. Please welcome the author of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley. Mary, welcome to the future.

Mary: Thank you, Danny. I must say, your “future” is much cleaner than I imagined. Less soot. More… glowing rectangles.

Danny: We call them screens. They’re how we ignore our families. But Mary, I brought you here because you wrote Frankenstein over 200 years ago, and yet, every time we talk about CRISPR, your book comes up. We talk about “Franken-foods” and “Franken-science.” Do you feel vindicated? Or just horrified that we didn’t listen?

Mary: Vindicated is a strong word. One does not wish to be right about the end of the world. But I am not surprised. You see, Danny, Frankenstein was never really about a monster. It was about a man. It was about Victor. It was about the arrogance of thinking that because we can do something, we must do it. Victor looked at death and saw it not as a natural boundary, but as a technical problem to be solved. It seems your scientists have adopted the same view.

Danny: That’s exactly it. We view aging and disease as “bugs” in the code. In the article, I used the metaphor of a red pen. We found the manual of life (DNA), and now we have a red pen (CRISPR) to edit it. Does that metaphor frighten you?

Mary: A red pen? How quaint. Victor had a shovel. He had to dig up graves to find his materials. He had to stitch together dead flesh. Your method is much more elegant, I admit. Invisible scissors cutting invisible threads. But the intent is the same. It is the desire to perfect the imperfectible. You say you want to “edit” the code. To edit implies you know the story better than the author. Who is the author, Danny? Nature? God? Chance?

Danny: That’s the big question. Most scientists today would say “Evolution” is the author, and that Evolution is a sloppy writer. It makes typos. It gives kids leukemia. It makes wisdom teeth that don’t fit in our jaws. If we have the pen, shouldn’t we fix the typos?

Mary: Ah, the “Benevolence” argument. Victor started with benevolence too. He wanted to “banish disease from the human frame.” It sounds so noble. Who could argue against curing a child of pain? But the road to the charnel house is paved with noble intentions. You start by fixing the wisdom teeth. Then you fix the height. Then you fix the intelligence. And soon, you have created a being that is not human, but a product. And what happens when the product does not behave as the manufacturer intended?

Danny: That’s the “Monster” scenario. In your book, the creature isn’t born evil. He becomes evil because he is rejected. Because he is lonely.

Mary: Precisely. He was a “Designer Baby” who was abandoned by his designer. Victor was horrified by his creation because it wasn’t beautiful. He wanted a god; he got a wretch. Now, imagine your CRISPR babies. Parents will pay thousands of dollars to edit their child’s genes. They will order blue eyes, high IQ, musical talent. They will design a Mozart. But what if the child grows up and wants to be a plumber? What if the child is unhappy? Will the parents love the child, or will they look at him like a defective toaster and ask for a refund?

Danny: That is a terrifying thought. The commodification of children. We move from “unconditional love” to “conditional love based on specs.”

Mary: It is the ultimate hubris. You are stealing the child’s destiny before they even draw breath. In my time, we believed a child was a gift from God, a mystery to be unfolded. You seem to believe a child is a project to be optimized. It drains the humanity out of the human experience.

Danny: Let’s talk about that word “Hubris.” You subtitled your book The Modern Prometheus. Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man, and was punished for it. Do you think CRISPR is the new Fire?

Mary: Fire is a tool. You can cook your dinner with it, or you can burn down your neighbor’s house. But genetics… genetics is not just a tool. It is the clay itself. Prometheus stole the power of the gods; you are stealing the blueprint of the gods. It is a much more dangerous theft. Fire changes the environment; genetics changes the user. If you change the user, Danny, do you not eventually lose the definition of “human”?

Danny: That’s the “Ship of Theseus” paradox. If you replace every part of the boat, is it the same boat? If we edit out all our flaws, are we still us?

Mary: And what are flaws? That is what chills me. You talk of “curing” deafness or blindness. But I have known blind poets who saw the world more clearly than anyone with eyes. I have known “sickly” people—my own husband, Percy, was often unwell—who created beauty that will last forever. If you scrub the genome clean of struggle, do you also scrub it clean of genius? Victor Frankenstein wanted to create a being without weakness, and he created a being without a soul.

Danny: You mentioned your husband, the poet Percy Shelley. And you hung out with Lord Byron. These were intense, dramatic, brilliant men. If they had access to CRISPR, would they have used it?

Mary: Oh, Lord Byron would have undoubtedly edited himself to be even more handsome, if that were possible. He was vain enough to demand a new chin. And Percy… Percy was a radical. He believed in the perfectibility of man. He probably would have embraced it. He would have written soaring odes to the DNA helix. “O Wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being, scatter my nucleotides among mankind!”

Danny: That was a solid impression.

Mary: Thank you. But I was always the dark anchor to their kites. I saw the shadow. I saw that if you make man perfect, you make him monstrous. Because a perfect man has no need for others. He has no need for sympathy. He has no need for love. Vulnerability is the glue of society, Danny. If we are all invulnerable gods, we will be incredibly lonely.

Danny: “Vulnerability is the glue of society.” I’m writing that down. That connects to what we discussed in the article about the “Wealth Gap of Genes.” If only the rich can afford these edits, we create a biological caste system.

Mary: You already have a caste system. I saw it in England. The rich ate better, lived longer, and looked healthier than the poor in the coal mines. But at least the poor man could say, “Underneath these rags, I am made of the same flesh as the King.” With your technology, that will no longer be true. The rich will not just be better dressed; they will be biologically superior. They will be a different species. They will look at the poor not as fellow men, but as chimpanzees. It will be the return of the Aristocracy, but this time, the “blue blood” will be literal.

Danny: That’s the plot of the movie Gattaca. Have you seen it?

Mary: I have not. I have been dead.

Danny: Right. Sorry. Well, in the movie, there are “Valids” (genetically perfect) and “Invalids” (natural births). The Invalids are the underclass. It feels like we are walking right into that.

Mary: You are running into it. And you are cheering as you run. That is the nature of the “Modern Prometheus.” You are so dazzled by the spark that you do not see the forest fire until you are burning.

Danny: I want to ask about “De-Extinction.” We talked about bringing back the Woolly Mammoth. You wrote about bringing back the dead. Reanimation. Is bringing back a Mammoth a cool science project, or is it a Frankenstein move?

Mary: It is a parlor trick. A very expensive parlor trick. Why do you want the Mammoth? To put it in a zoo? To stare at it?

Danny: Ideally, to restore the Arctic ecosystem. They stomp down the permafrost.

Mary: Ah, the ecosystem. You destroyed the ecosystem, so now you must build a monster to fix the ecosystem. It is a cycle of interference. Victor Frankenstein raided the graveyards to build his creature because he couldn’t accept that death was final. He couldn’t let go. You cannot accept that the Mammoth is gone. You cannot accept that you killed it. So you try to resurrect it to assuage your guilt. But the Mammoth will be alone. It will be a hairy elephant in a world of hairless apes. It will be a curiosity. And curiosities are rarely treated with kindness.

Danny: You think the Mammoth would be lonely?

Mary: I think it would be as lonely as my creature. It would look for its kin and find only tourists with iPhones.

Danny: That’s… incredibly sad.

Mary: Tragedy is my specialty, Danny.

Danny: Let’s pivot to something slightly more hopeful. Is there any version of this technology you approve of? If we could edit out the gene for, say, the bubonic plague? Or the gene that causes a child to die in agony at age four?

Mary: I am a mother, Danny. I lost three children before they reached adulthood. Clara died at one year old. William at three. I know the grief of the small coffin. If a man in a white coat had come to me and said, “I can save William with this red pen,” I would have let him write anything he wanted. I would have given him my soul.

Danny: So you understand the temptation.

Mary: I understand it in my marrow. That is why it is so dangerous. If it were purely evil, it would be easy to resist. But it is not evil; it is salvation. How do you say “no” to salvation? How do you tell a mother she must bury her child because of “ethics”? You cannot. And that is why you will not stop. You will open the door to save the child, and the monster will slip in behind you.

Danny: Wow. That is the nuance we were missing. It’s not about mad scientists; it’s about desperate parents.

Mary: Victor was not mad, initially. He was grieving. His mother died, and he couldn’t save her. Frankenstein is a book about grief gone wrong. Your CRISPR revolution is driven by the same grief. You want to stop death. It is the most human desire there is. But death is the price of life. If you refuse to pay the price, you might find that what you buy is not life, but something… else.

Danny: You really have a way of bringing the room down, Mary.

Mary: I am a Gothic novelist. We don’t do “light and breezy.”

Danny: Fair enough. Let’s talk about the “Germline” editing again. Changing the future generations. We talked about how that’s the red line for scientists today.

Mary: It is the red line because it removes consent. You are making decisions for the year 2300. How dare you? You do not know what the world will be like in 2300. Maybe they will need the gene for anxiety to survive a world of tigers. Maybe they will need the gene for sickle cell to survive a new plague. By streamlining the human race, you are making it fragile. Diversity is strength. Uniformity is weakness.

Danny: “Diversity is strength.” That’s a biological fact. Monocultures die out.

Mary: Indeed. If you make everyone a Mozart, who will bake the bread? And if you make everyone “perfect,” you will eventually define “perfect” in a very narrow way. In my time, “perfect” meant a white, British male with land. I imagine your definition hasn’t expanded as much as you think.

Danny: Ouch. Yeah, our algorithms are still pretty biased.

Mary: The pen is only as wise as the hand that holds it. And the human hand is shaky. It is guided by greed, by vanity, by fear. Until you edit the human heart, Danny, you should be very careful about editing the human cell.

Danny: “Until you edit the human heart.” That’s the quote of the episode. So, what is your advice to us? We have the scissors. We aren’t going to throw them away. How do we use them without creating a monster?

Mary: You must love the monster.

Danny: Excuse me?

Mary: That was Victor’s crime. Not that he created the being, but that he abandoned it. He didn’t take responsibility. If you are going to create these “CRISPR babies,” these edited humans, these de-extinct mammoths… you must take care of them. You must treat them as souls, not experiments. You must not recoil from them if they are not perfect. You must integrate them into the human family. If you treat them as products, they will destroy you. If you treat them as children, perhaps there is hope.

Danny: So the antidote to the danger of technology isn’t less science, it’s more… empathy?

Mary: Empathy is the only thing that can contain Prometheus. Science gives you power; empathy gives you control. Without empathy, you are just a child playing with matches in a gunpowder factory.

Danny: You know, for a woman who writes about graveyards and reanimated corpses, that’s actually a beautiful message.

Mary: I find beauty in the darkness. It is where the light shines brightest.

Danny: One final question. If you could use CRISPR on yourself… just a tiny edit. Would you?

Mary: I suppose… I would edit out the seasickness. I traveled quite a bit, and I was always dreadfully ill on boats.

Danny: Really? The author of the greatest horror novel of all time just wants to not throw up on a boat?

Mary: Even a prophet prefers a steady stomach, Danny.

Danny: Mary Shelley, you are a legend. Thank you for haunting us today.

Mary: The pleasure was mine. Do try not to destroy the species before I visit again.

Danny: We’ll try our best. No promises.

Mary: Beware the red pen…

Danny: And there you have it. Mary Shelley, reminding us that while we might have the blueprint of life, we are still reading it by candlelight. The technology has changed, but the questions—about hubris, about love, about what it means to be human—haven’t aged a day.

0 Comments