Indian Literature

INTRODUCTION

Indian Literature, writings in the languages and literary traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The subcontinent consists of three countries: India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The political division of the area into three nations took place in the 20th century; before that, the entire region was generally referred to as India. For centuries Indian society has been characterized by diversity—the people of modern India speak 18 major languages and many other minor languages and dialects; Urdu is the principal language of Pakistan, and Urdu and Bengali are used in Bangladesh. The people of the subcontinent also practice all the world’s major religions. Throughout its history, India has absorbed and transformed the cultures of the peoples who have moved through the region. As a result, the Indian literary tradition is one of the world’s oldest and richest.

Religion has long exercised a strong influence on Indian writing. The major religions of the area have been Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Islam. Throughout the history of Indian literature, certain religious doctrines have formed common threads. One such doctrine is karma—the chain of good and bad actions and their inevitable consequences, which result in the repeated birth and death of the soul. The mythology of the dominant Hindu religion portrays the deities Vishnu, Shiva, the Goddess (Devi), and others. This mythology has influenced Indian texts, from ancient epics in the Sanskrit language to medieval poems in the various languages of different regions to modern works in English.

The Vedas, which are Hindu sacred texts, are the earliest examples of Indian literature. The Vedas were composed between about 1500 BC and 1000 BC in Old Sanskrit, also called Vedic Sanskrit. This language belongs to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family. Indo-Aryan languages dominated northern India in ancient times, and Sanskrit became the major language of Indian religious and philosophical writing and classical literature. It also served as a common language with which scholars from different regions could communicate. No longer spoken widely, it is maintained as a literary language in modern India, meaning that people still use it for written works.

The emergence of the popular religions Buddhism and Jainism in the 6th century BC gave rise to literature in Pali and in the several dialects of Sanskrit known as Prakrit (meaning “natural language”). Meanwhile, Tamil, a Dravidian language, emerged as the most important language in the south. A recorded literature in Tamil dates from the 1st century AD. Rich literary traditions have emerged in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, which are modern languages that developed from Old Tamil and its dialects.

Between the 10th and 18th centuries, the medieval dialects of the earlier languages evolved into the modern languages of India. Eighteen of these languages now have official status in India, as does English. As the different tongues evolved, a distinctive literature with particular styles and themes developed in each tongue. At the same time, Indian literature was influenced by the Persian language and its literature, which various Muslim conquerors brought to the Indian subcontinent. Muslims also introduced Islam to India, and Islamic philosophy and traditions affected Indian literature. After the British became active in India in the 1700s, English language and writing had a significant impact on Indian literature.

Oral traditions have always been important in Indian literature. Many storytellers present traditional Indian texts by reciting them, often with improvisation. Others use song, dance, or drama to tell tales. In both its oral and written forms, Indian literature has produced great works that have influenced national and regional literary traditions in other parts of the world.

BEGINNINGS

The earliest Indian literary works that survive are religious and heroic texts written in Sanskrit or in languages related to it. These texts were produced between about the 16th century BC and the 1st century AD by a people known as the Aryans. The Aryans were cattle herders who were originally nomadic, traveling from place to place. They eventually settled and became cultivators of the land, establishing kingdoms in north India.

Religious Texts

The sacred Vedas were composed in Old Sanskrit by Aryan poet-seers between about 1500 BC and about 1000 BC. The Vedas are compilations of two major literary forms: hymns of praise to nature deities and ritual chants to accompany Aryan religious rituals. There are four Vedas: the Rig-Veda, the Yajur-Veda, the Sama-Veda, and the Atharva-Veda. Considered divine revelations received by the poets, the Vedas constitute the fundamental scripture of the Hindu religion and are used in the sacramental rites of Hinduism.

The Vedas were passed from generation to generation by the spoken word, not by the written word, because Hindus believe that mantras, the utterances of the Vedic hymns out loud, are sacred cosmic powers embodied in sound. The Vedas were not written down until long after they were originally composed. Priests in modern India still recite the Vedas out loud.

After the Vedas were compiled, the Hindu priests composed the Brahmanas, which detail information about rituals. Appended to the Brahmanas are theological texts known as Aranyakas, and attached to these are the Upanishads. The Upanishads were composed between the 8th century BC and the 5th century BC by a group of sages who questioned the usefulness of ritual religion. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (Upanishad of the Great Forest, 8th century BC?), an important early Upanishad, consists of dialogues between teachers and their students about the individual soul’s unity with a divine essence that pervades the universe. The Upanishads are India’s oldest philosophical treatises and form the foundational texts of major schools of Hindu philosophy (see Indian Philosophy).

The major religious texts of Buddhism were compiled in three collections known as the Tipitaka (meaning “three baskets”). The Tipitaka, written in the Pali language, includes the teachings of the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. The most important of these texts include the Jatakas (Stories of the Births of the Buddha), which tell 547 stories of Buddha’s former births. In the tales, Buddha recounts how he was reborn in the form of animals, human beings, and nature deities as he worked toward enlightenment and, ultimately, toward release from the cycle of rebirths. This release is the aspiration of all Buddhists. The Jatakas and the major narratives and philosophical texts of early Buddhism eventually spread along with Buddhism to Sri Lanka, China, Japan, and the countries of Southeast Asia, including Thailand and Vietnam.

India’s third ancient religion was Jainism, which was founded by Mahavira. The early literature of Jainism flourished mainly in Prakrit dialects. Buddhist and Jain authors wrote many works in Sanskrit as well.

Heroic Texts

The most celebrated ancient heroic texts of India are the Mahabharata (The Great Epic of the Bharata Dynasty) and the Ramayana (The Way of Rama). These epics were composed in Sanskrit verse over several centuries and transmitted orally by bards. They describe how the Aryans established control over India and depict Aryan-Hindu life in northern India.

The written version of the Mahabharata is attributed to the legendary poet-editor Vyasa, but it took shape over several centuries from 400 BC to AD 400. The epic tells the tale of a dispute between two branches of the Bharata clan over the right to rule the kingdom. The dispute leads to a great war that involves all the Aryan clans and nearly results in their total destruction. The poet Valmiki, who lived around the 3rd century BC, put the Ramayana into form. This epic tells the story of the hero Rama, prince of Ayodhya and incarnation of the god Vishnu. Rama willingly accepts exile in the forest to redeem a promise made by his father. Rama’s wife Sita is then kidnapped, and Rama rescues her by slaying her abductor, the demon king Ravana.

The Mahabharata and the Ramayana provided the themes for important later literary works in Indian and Southeast Asian languages. These epics have been kept alive through various performance forms—from Ramlila plays in the Hindi language in north India (see Asian Theater) to the Kathakali dance-drama of Kerala (in south India) to the Wayang puppet plays of the island of Java. Recently, Hindi versions of both epics were made for Indian television, and the epics continue to be the most popular traditional literary texts in India.

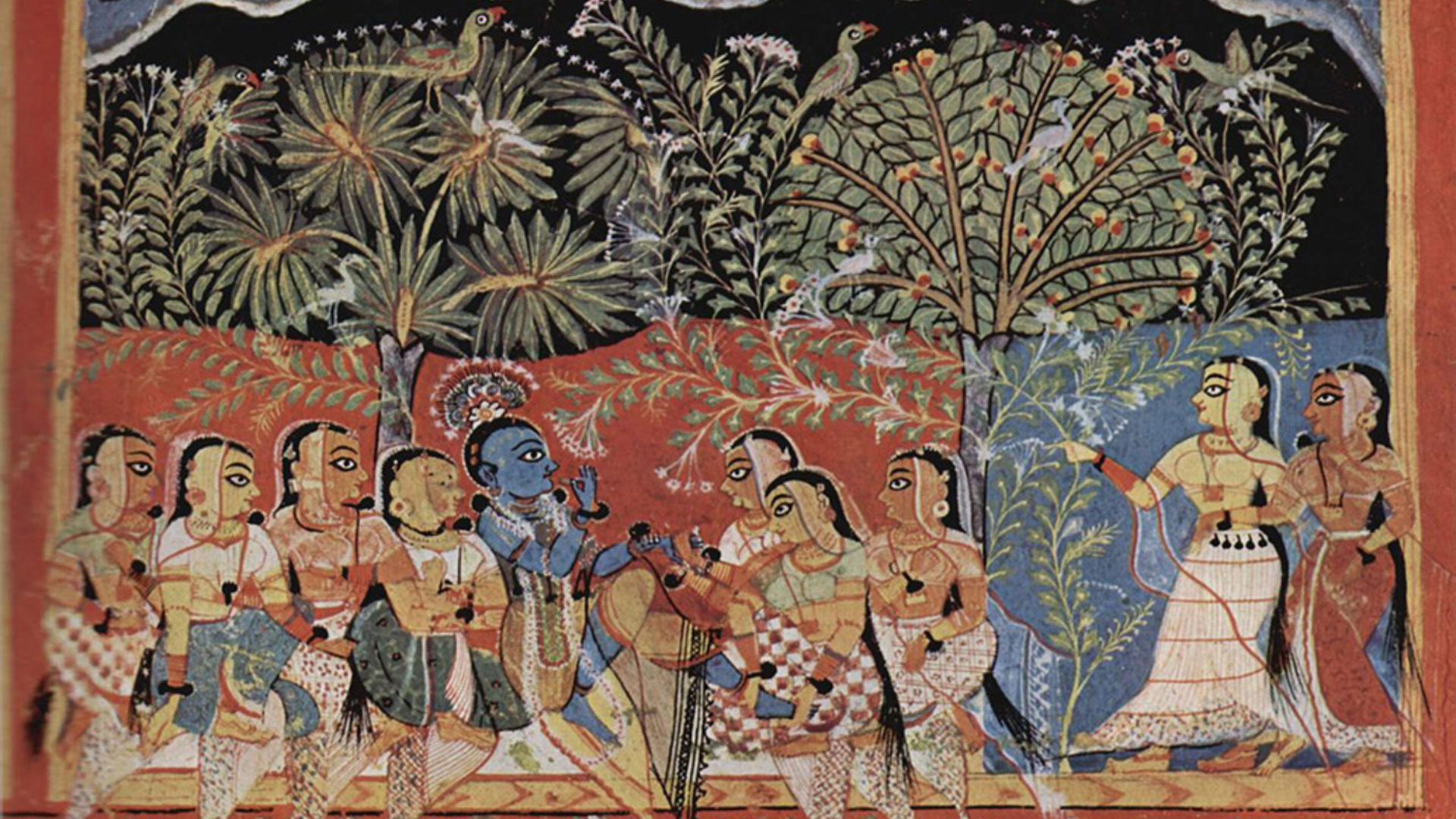

A major reason for the popularity of the epics is that their characters—heroes and gods in human form—convey the central ethical teachings and cultural values of Hinduism. These teachings and values are encapsulated in the term dharma, meaning “that which is right.” In fact, the Bhagavad-Gita (Song of the Lord), the authoritative text of religious ethics in Hinduism, forms part of the Mahabharata. In this dramatic dialogue, the god Krishna, incarnation of Vishnu, teaches the warrior Arjuna the right way to act in an ethical crisis. Arjuna, he says, should follow the guidelines of unselfish action and duty according to his place in society.

CLASSICAL LITERATURE

The dominant classical literary tradition in India developed in the Sanskrit language in the first few centuries AD. This literature had its great flowering in the era of the Gupta dynasty of north India, from 320 to 550. This was a time of great achievement in philosophy, the sciences, and the arts. Primarily reflecting the values of Hinduism, classical Sanskrit literature was nurtured at courts of kings and aristocrats and in scholarly gatherings; it expressed the interests of warriors (kshatriya) and scholars and priests (brahman), the elite of the four social classes (varna) of Hindu society. The other two social classes are merchants (vaisya) and laborers (sudra). (In Hinduism, a person’s social class is determined by birth. Each social class is further subdivided into communities called caste. Each caste is ranked as more pure or less pure than other castes. The caste system has been a traditional part of Indian society for centuries, although in modern times it has lost some force.)

Kavya was the major form of classical literature in Sanskrit. The term kavya denoted works that were composed primarily for pleasure and that employed complex literary conventions and elaborate metrical schemes. Kavya works aimed to depict the spheres of politics, commerce, and erotic pleasure. At the same time, these works subordinated these realms of human experience to the ethical ideals of dharma and the Hindu religious goal of moksha, liberation from karma and rebirth. Also important in kavya literature is the idea of rasa (mood), the experience of the essential mood or flavor of a work of art. The major kavya genres—epic, lyric, drama, and various types of fiction—were similar to the chief genres of premodern European literature.

Kalidasa, who lived in the late 4th century and early 5th century, is considered India’s preeminent classical poet. His epic poems include Raghuvamsa (Dynasty of Raghu) and Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger), which is a beautiful lyric poem about separated lovers. The most famous of Kalidasa’s works is his poetic drama Shakuntala (also known as Abhijnanashakuntala, Shakuntala and the Ring of Recollection). This drama tells the story of a love affair between a king and a woodland maiden named Shakuntala. Yet it is more than that. In this work, the poet transforms a simple tale into a lyrical and universal drama of the passion, separation, suffering, and reunion of lovers. Shakuntala had a profound impact on German author Johann Wolfgang Goethe and on other European writers who encountered it in translation in the 18th century.

Sanskrit drama, a rich pageant of mime, dance, music, and lyrical texts set in the courts of kings and aristocrats, was a productive classical genre. In addition to Kalidasa’s plays, noteworthy classical dramas include the lively urban comedy Mrichchhakatika (The Little Clay Cart) by the 5th-century writer Shudraka and the romantic Malati-Madhava (Malati and Madhava) by the 8th-century writer Bhavabhuti.

Foremost among the works of fiction in classical Sanskrit is the Panchatantra (The Five Strategies) by Vishnusharman. This work is a collection of stories in prose and verse that were composed between the 3rd century BC and the 4th century AD. The stories, which feature animals as the characters, teach lessons about human conduct. Two major 7th-century prose romances are Kadambari by Bana and Dashakumaracharita (The Adventures of the Ten Princes) by Dandin. The popular work Kathasaritsagara (Ocean to the Rivers of Stories), by the 11th-century writer Somadeva, is a collection of witty tales in verse about the love affairs and schemes of merchants, princes, and other adventurers. The Panchatantra and the Kathasaritsagara both use the technique of telling stories within the framework of a main story. This approach, and the technique of using animals as characters, later migrated to European literature through Arab translators and travelers.

The brief lyric verse form called the muktaka (independent verse) is perhaps the quintessential genre of classical Sanskrit poetry. A muktaka is a short poem consisting of four lines of verse, each with an identical pattern of syllables. (A line in a muktaka is called a pada, meaning “quarter” in Sanskrit.) Sanskrit poets composed such poems in a variety of meters. The 7th-century writer Bhartrihari wrote epigrams on wisdom and worldly conduct in this genre. The 7th-century writer Amaru used the muktaka form for his erotic vignettes in the Amarusataka (The Century of Love). The verses of these works are still memorized by people interested in Sanskrit literature.

Along with the courtly literature, Sanskrit also nurtured the Puranas, a genre of mythological narratives that were written well into the medieval era. According to tradition, each Purana is supposed to deal with five topics: the

creation of the universe, the destruction and re-creation of the universe, the genealogy of the gods and holy sages, the reigns of the Manus (legendary Hindu figures), and the histories of the kings who trace their ancestry to the sun and moon.

In southern India, beginning in the 1st century AD, a magnificent body of nonreligious poetry was written in the Tamil language. The Tamil poets—both men and women—treat sexual love and the heroic ideals of the Tamil people through symbolic landscape images, powerful language, and delicate psychological touches. The early Tamil poems became the foundation of literary traditions in other languages of south India. They later influenced medieval poetry of religious devotion in all the Indian languages.

The literature produced in Tamil between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD is dominated by Jain and Buddhist values combined with Tamil views of the sacred. Tirukkural (The Sacred Short Sayings, 4th century AD?), containing Tiruvalluvar’s brief verses on ethical behavior, has a strongly Jain flavor; it remains a treasured Tamil classic. In the epic Cilappatikaram (The Narrative of the Ankle Bracelet, 5th century?), the Jain monk Ilanko depicts the transformation of the chaste wife Kannaki into a goddess after she avenges the unjust death of her husband. In the Buddhist poet Cattanar’s long poem Manimekalai (The Girdle of Gems, 6th century?), the beautiful heroine Manimekalai rejects worldly life and becomes a Buddhist nun.

Poet-saints called Nayanars and Alvars, who led popular movements of devotion for the Hindu gods Shiva and Vishnu, wrote the Tevaram and the Nalayira Divya Prabandham, respectively, between the 6th and 8th centuries. These hymns served the cause of bhakti, a new aspect of religion that dominated Indian literature in the medieval period. Bhakti literature is discussed below. The hymns of the Nayanar and Alvar poets are sung in temple rituals in southern India to this day.

MEDIEVAL LITERATURE: THE RISE OF THE REGIONAL LANGUAGES

By the 10th century the older Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages and dialects had grown into full-blown languages. Each region also began to develop its own distinctive culture. As a result, regional literatures developed in each of the new regional languages, under the patronage of local rulers.

Buddhism had weakened as a religious force in India, but the philosophies of Hinduism and Jainism were still strong. From the 12th century onwards, Indian literature shows the influence of yet another religion, Islam. During medieval times, a succession of Islamic dynasties conquered many territories in north and central India. Some Indian languages were influenced by Islamic religion and culture as well as by the Persian and Arabic languages and the literatures of these two tongues. These influences affected the development of the Hindi language, resulting in the emergence of Urdu, a particular form of Hindi. The Urdu language has a large number of Persian and Arabic words, and is written in the Arabic script.

Although the literatures of the regional languages were as diverse as the languages and subcultures they represented, they also shared a number of characteristics. For example, the older Sanskrit myths, epics, and kavya poems served as sources for some of the best works in the new languages. But also, for the first time in Indian literature, unique versions of local myths, legends, romances, and epics emerged.

Bhakti: Devotional Literature

The most important genre of the medieval era was the lyric poetry of authors who belonged to Hindu movements dedicated to bhakti. Bhakti was an aspect of religion that involved passionate, emotional devotion to a particular god. Bhakti authors, who are revered as saints, addressed the devotional poems that they wrote to the major Hindu gods and goddesses, especially Shiva, Vishnu, Krishna, Rama, and the Goddess (Devi). These poems are among the earliest and most popular literary works in each of the regional languages.

Bhakti lyric poems share a number of characteristics. Unlike earlier Indian literature in Sanskrit, they are works of a personal and emotional character. Sung by devotees, the poems often speak from the perspectives of marginalized and excluded groups in Indian society, voicing social criticism. Some of the major bhakti poets were women, and men of the lower castes were also represented.

Notable early bhakti writers include the poets Basava and Mahadevi of the Virashaiva sect. In their Kannada-language poems of devotion to the god Shiva, called vacanas (utterances), these authors criticize social injustice and conventional morality. Other bhakti writers were Tukaram and Bahinabai, who composed poems in the Marathi language; Kabir, Tulsidas, and Surdas, who wrote in dialects of Hindi; and the Vaishnava poets Vidyapati and Chandidas, who wrote devotional poems in Bengali, celebrating the love of Krishna and his beloved, Radha. One of India’s best-known female poets is the bhakti poet Mira Bai, a 16th-century writer who composed poignant songs in Rajasthani-Hindi about her love for the god Krishna.

Other Literary Forms

The great literary works of medieval India include biographies on the bhakti saints. The Tamil work Periyapuranam (Great Narrative), by the 12th-century writer Cekkilar, tells about the lives of the Tamil Nayanar saints. Chakradhara’s Lilacharitra (Narrative of the Divine Play, 1280?) in Marathi is about the Mahanubhava saints. Palkuriki Somanatha’s Basavapurana (Narrative of Basava, 13th century) in Telugu is about the Virashaiva saints.

The Mahabharata and the Ramayana epics provided the themes for some of the best works in the regional languages. The 12th-century Tamil Iramavataram (Descent of Rama) by Kampan and the 16th-century Hindi Ramcharitmanas (The Holy Lake of the Acts of Rama) by Tulsidas are literary masterpieces of their languages. Both of these works are retellings of the Ramayana story.

Each Indian regional language has romances, folk epics, and ballads focusing on local heroes, heroines, gods, and goddesses. Some of these works are transmitted mainly in oral traditions and are not attributed to any individual. Works of this type include the epics of the heroes Pabuji and Devnarayan in the Rajasthani language, and the Hindi epics Candayan and Dhola. The Pabuji epic describes the exploits of the Rajput warrior Pabuji, who dies in battle and is later worshiped as a god. The Dhola epic treats the themes of the exploits of King Nal and the birth of his son Dhola, the adventures of Dhola, and the beautiful princess Maru’s love for Dhola. The principal characters in many of the oral narratives belong to the lower castes in the Hindu caste system. In the Devnarayan story, Devnarayan, an incarnation of the god Vishnu, is born as a cowherd and fights against Rajput warriors to avenge the deaths of heroes of the cowherd caste. Chandaini, also known as Lorik-Chanda, describes the love affair of the heroine Chandaini, a married woman, with the cowherd Lorik, who is also married.

Some epics are attributed to specific authors. The Hindi Prthviraj Raso (Heroic Narrative of King Prthviraj), by Chand Bardai, sings the exploits of the 12th-century King Prithviraj Chauhan of Delhi, including his resistance to the invader from Central Asia, Muhammad of Ghur. Padumavat (1540), a Hindi romance based on Hindu legends but written by the Sufi Muslim poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi, illustrates the blurring of boundaries between Hindu and Muslim cultures in this period.

Regional Differences

Eighteenth-century works such as Risalo, a collection of mystical poetry in the Sindhi language by Shah Abdul Latif, and the Punjabi poet Bullhe Shah’s poems in a Sufi Muslim genre called kafi, reflect the languages and cultures of the northwestern areas of India (regions that today are in Pakistan). A genre of narrative poems called mangal-kabya (poem of good fortune and grace) is unique to Bengali, a language of eastern India. These poems tell tales of great goddesses and their treatment of their devotees and are also full of details about everyday life in medieval Bengal. Celebrated examples of this genre are the Candi-mangal (The Grace-Poem of the Goddess Candi, 1590) by Mukundaram and the Annada-mangal (The Grace-Poem of the Goddess Annada, 1752) by Bharatchandra Ray.

In southern India, beginning with the Hindu Vijayanagar Empire (1336-1565), writers used both Sanskrit and the Dravidian languages related to Tamil. Speakers of Tamil continued to build upon the rich classical and devotional traditions in that language. In its early period, works in Kannada, another Dravidian language, were dominated by Jain religious themes. An example is the Adipurana (History of the First One), the 10th-century author Pampa’s biography of the Jain holy figure Rishabha. Writers in the Telugu language in particular excelled in kavya-style poetry. These works, though influenced by Sanskrit models, had features unique to Telugu language and culture. An outstanding example is the Shringaranaishadhamu (The Love of King Nala), in which the 14th-century poet Srinatha retells the well-known Sanskrit epic tale of the travails of King Nala and Queen Damayanti. Kerala, in the western part of south India, developed a rich literature in a language called Manipravalam (meaning “gem and coral”), which was a mixture of Malayalam and Sanskrit.

In medieval times, the Muslim sultans of the kingdoms in Deccan (central India) and the Muslim rulers of Delhi nurtured literature in the Persian language. Especially important were the Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb, who ruled India from 1526 to 1707. These rulers introduced Persian as the language of administration, education, and cultured discourse. Several Persian literary forms gained popularity, including biographical works. An important example is Akbar-nama, the biography of Akbar written by his courtier Abu’l Fazl. The dastan, narratives of adventure and romance that were based on Persian and Arabic stories, also expanded the literary landscape.

The most important Persian literary form to be adapted in the Indian context was the ghazal, a poem of rhymed couplets (two-line stanzas). The main theme of the ghazal is love, both between human beings and between the human being and God. At first, most Indian poets wrote ghazals in Persian, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, Urdu, a form of Hindi written in Arabic script, became the preferred language for the ghazal. Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Ghalib head the list of eminent Urdu poets.

Ghalib’s ghazals, considered classics of the genre, capture the profound melancholy, striking imagery, and contemplative, introspective qualities that characterize ghazal poetry. In his work, Ghalib comments on the passing of a great civilization as he reflects on the political turmoil of his time. From 1857 to 1859, in an event known as the Revolt of 1857 or the Sepoy Rebellion, Indian troops employed by the English East India Company revolted against British rule in India but were subdued. The Mughal emperor at the time, Bahadur Shah II—himself an Urdu poet of merit—was tried for treason and exiled to Burma (now Myanmar).

COLONIAL PERIOD TO INDEPENDENCE

The British became a colonial power in India in the 1700s and established control over much of the subcontinent by the early 1800s. In 1835 the British colonial government introduced English education for upper-class Indians so that they could serve in the administration of the colony. English education exposed Indians to Western ideas, literary works, and values. At the same time, translations of Indian literary works by Western scholars stimulated Indians to approach their own literary and cultural heritage from new perspectives. One such translation was a 1789 version of the 4th-century Sanskrit play Shakuntala, translated by British linguist Sir William Jones.

The introduction of the printing press in India made possible the establishment of newspapers and journals in English and Indian languages. These media created new opportunities for Indians to write, publish, and communicate across their large country. A major development in this period was the Bengal Renaissance, a cultural movement among Bengalis in Calcutta (now Kolkata), which was both the British capital and a center of Bengali culture. The writers of the Bengal Renaissance led the way in synthesizing Indian and Western ideas in literature and culture.

Poetry

Of the early examples of modern writing in India, some of the best were in poetry. Famed writer Rabindranath Tagore began his career in the late 19th century with innovative poetry in the Bengali language, but he also drew on traditional forms of poetry and performance. Perhaps his best-known work is Gitanjali (Song Offerings, 1910), a collection of poems. Many of Tagore’s poetic and musical dramas, such as Dak-ghar (The Post Office, 1912), were performed at Santiniketan, the school that he founded near Calcutta. In 1913 Tagore won the Nobel Prize for literature, becoming the first non-European winner of the award.

Two female poets of the time, Toru Dutt and Sarojini Naidu, both Bengali by birth, distinguished themselves with works in English. Dutt died when she was only 21 years old, but Naidu had a long and illustrious career in literature and politics. The Golden Threshold (1905) is a major collection of her poems, which often focus on themes relating to Indian cultural traditions and Indian women’s lives. Naidu also wrote speeches and essays, and she became a leader of the nationalist movement, which sought independence from Britain. Subrahmaniya Bharati wrote some of the earliest prose and poetry in the modern form of the Tamil language. His poems reflect his passionate dedication to the cause of freedom from British rules, and his desire for progress for India as a modern nation. Other authors, such as the noted Hindi poets Sacchidanand Vatsyayan, Suryakant Tripathi, and Mahadevi Varma (a female author and winner of the literature prize of the Indian Academy of Letters), wrote works of a more introspective, personal character.

Prose

The novel and short story, both new forms in Indian writing, dominated modern Indian literature in the 19th century. Writers used these genres to create realistic portrayals of individuals and to address contemporary social issues. This marked a change from earlier Indian literature, much of which was preoccupied with ideals and broad social types. The new authors came from the English-educated class of Indians and were influenced by the progressive ideals of the Bengal Renaissance. They also participated in the rising movement for political rights and representative government for Indians. (The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885.) Nationalism and the criticism of oppressive social practices were favorite topics among the writers of the period.

The poet Rabindranath Tagore was also a major prose writer, and a pioneer in the short-story form in Bengali. His short stories, such as the ones in The Hungry Stones and Other Stories (1916), depict the lives of ordinary villagers in East Bengal. Tagore’s contemporary, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, who was one of the leaders of the Bengal Renaissance, had turned to writing in the Bengali language after writing a novel in English, Rajmohan’s Wife (1864). Chatterjee’s Bengali novels deal with contemporary social issues such as the pitiful condition of widows (Bishabriksha; The Poison Tree, 1873) and with historical and nationalist themes—as in Ananda Math (The Abbey of Bliss, 1882). Tagore provoked controversy with his criticism of nationalism in his most famous novel, Ghare-baire (1915; The Home and the World, 1919). Writers from other regions began working in regional languages in the late 1800s. Govardhanram Tripathi’s novel in the Gujerati language, Saraswatichandra (1887), and Chandu Menon’s Malayalam work Indulekha (1889) are only two of the many examples.

Many of the works of Tagore, Chatterjee, and other novelists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries focus on the ways in which Indian women of the middle and upper classes were oppressed by their lack of economic opportunity, education, and freedom of movement. The heroines of Tagore’s novels Nashtanir (1901; The Broken Nest, 1971) and Ghare-baire as well as the female characters in his short stories, represent the oppression not only of women but of all people. A concern with domestic life dominated the fiction of the popular writers of the following era, such as the Bengali novelists Saratchandra Chatterjee and Ashapurna Devi.

Towards the end of the 19th century, women from the Indian middle class began writing. Many of them wrote works on women’s issues and social reform. Notable examples include Tarabai Shinde’s essay in Marathi, “Stri Purush Tulana” (A Comparison Between Women and Men, 1882); Pandita Ramabai Saraswati’s The High-Caste Hindu Woman (1887), a book in English about Indian women; and Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s writings in Bengali on the constraints of purdah, a system of seclusion of women.

In the years between World War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1939-1945), three movements influenced and stimulated Indian writing. The first was the nonviolent movement toward freedom for India, led by Mohandas Gandhi. The others were the international movements of Marxism (see Karl Marx) and socialism, which advocated better living and working conditions for laborers. Raja Rao wrote Kanthapura (1938), an English novel about the involvement of Indian villagers in the Gandhian freedom movement. Mulk Raj Anand’s English novels Untouchable (1935) and Coolie (1936) deal with the injustices of the caste system and oppressive labor practices.

Two great novels of social realism and critique of injustice were published in 1936: Hindi writer Premchand’s Godan (translated 1957), an epic novel of peasant life in North India, and Bengali novelist Manik Bandyopadhyay’s Putul Nacher Itikatha (Puppet’s Tale, translated 1968), about rural Bengal. During this time Sir Muhammad Iqbal gained fame both as a writer and as an advocate for separate Hindu and Muslim nations. R. K. Narayan, who began his distinguished writing career with the English novel Swami and Friends (1935), stands apart from most of the writers who flourished in the mid-1930s, because his novels focus on character and human interaction rather than on larger social issues.

INDEPENDENCE ONWARDS

India gained independence from Britain in 1947, a year that marks a watershed in the course of modern Indian literature. Independence forced writers to grapple with the ideals and realities of being part of a new nation. On one hand, there was euphoria at the new freedom. On the other hand, as part of independence, the Indian subcontinent was divided into two separate nations, India and Pakistan—India dominated by Hindus and Pakistan by Muslims. (In 1971 part of Pakistan became the independent nation Bangladesh.) During the decades leading up to independence, Hindus and Muslims had become increasingly divided within India. The partition of the newly independent country into two nations was accompanied and followed by severe violence. Especially hard hit were the new border areas: the divided territories of Punjab in the northwest and Bengal in the northeast, and the disputed area of Kashmīr at the India-Pakistan border.

Partition caused millions of people to be uprooted from their home territories or to suffer division within their families. Much Indian and Pakistani fiction after 1947 explores, in one way or another, the effects of partition on Indian culture. Another ongoing concern is the rapid rate of change that India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are experiencing in an era of increased globalization and of the migration of people from the Indian subcontinent to other parts of the world, especially Western countries. A significant development in Indian literature in the mid- and late 20th century was the rise of female writers and feminist writing.

While many Indian writers continue to write in Indian languages, English is also an important tongue for Indians and those of Indian origin. Within India, readers have increasing access to literature in the languages of regions other than their own. This access is largely due to the efforts of the Indian National Academy of Letters to promote the translation of contemporary works from their original language into other Indian languages and into English.

Partition and Change

Partition has been a literary subject in many of the Indian languages, as well as in English. Khushwant Singh’s English novel Train to Pakistan (1956) is one of the earliest novels to evoke the horrors of the violence that accompanied partition. Saadat Hasan Manto is an author who lived first in India and then in Pakistan. In his eloquent Urdu short stories, Manto bears witness to the personal trauma as well as the societal and national tragedies brought about by partition. In his most famous story, “Toba Tek Singh,” (translated in Kingdom’s End and Other Stories, 1987), Manto depicts the dislocation of populations at partition as an absurd event seen from the perspective of the inmates of a lunatic asylum. Pakistani writer Bapsi Sidhwa’s gripping English novel Ice-Candy-Man (1988; later published as Cracking India, 1991) portrays the events of 1947 through the eyes of a little girl. Indian writer Bhisham Sahni’s Hindi novel Tamas (1974; Kites Will Fly, 1981) is another chronicle of partition.

After 1947, the realist and progressive trends in Indian fiction, represented by earlier writers such as Premchand and Mulk Raj Anand, continued in the fiction of writers from every region of India. Notable works include U. R. Ananta Murthy’s novel in Kannada Samskara (A Rite for a Dead Man, 1965), a work about the decaying Brahman community in a village in the state of Karnātaka; Hindi writer Shrilal Shukla’s Raga Darabari (The Melody Darbari, 1968), a novel about rural life in north India; Chemmeen (Shrimp, 1962), Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s celebrated Malayalam novel of the fishing community in the state of Kerala; and Vyankatesh Madgulkar’s Bangarwadi (1955, The Village Had No Walls, 1958), a Marathi novel about shepherds in the state of Mahārāshtra.

An important development in regard to literature with a social conscience is the movement of Dalit (Oppressed) writing. In Dalit writing, men and women of marginalized and low-caste communities write poetry and fiction about their own lives and communities. Poisoned Bread (1992), edited by Arjun Dangle, is an important anthology of Dalit writing. The volume includes works by Namdeo Dhasal and other major Dalit writers.

In the 1960s and 1970s experimental and avant-garde trends in Indian writing were seen in both poetry and drama. Well-known plays include Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq (1964), a modern political satire based on the life of a sultan of medieval Delhi; Marathi playwright Vijay Tendulkar’s Shantata! Court Chalu Ahe (Silence! The Court Is in Session, 1978); and Badal Sircar’s Bengali drama Evam Indrajit (1962; And Indrajit, 1979).

After independence, female writers have become more prominent in India. In exquisitely crafted, passionate short stories in Urdu, Ismat Chughtai depicts the injustices of women’s lives in Indian society, especially in Muslim circles in India. Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi has won great acclaim for her short stories, in which she draws upon her experience working with marginalized groups in eastern India. For her achievements, Devi was awarded the Indian government’s highest literary award. Creating an array of memorable characters in powerful novels and short stories such as “Stana-dayini” (“Wet Nurse,” 1976), Devi exposes the exploitation of women and of the lower classes, and the double exploitation of women of the lower classes. Anthologies such as Women Writing in India (2 volumes, edited by Susie Tharu and K. Lalita, 1991, 1993) have helped make the important

contributions of women and feminist writers accessible to wider audiences.

Writing in English

Indians have written novels in English from the 19th century onwards. But only in the 1930s, with the novels of Raja Rao, Mulk Raj Anand, and R. K. Narayan, did international writing circles begin to take notice of Indian writing in English. Between the 1950s and 1980s, Narayan in particular gained attention with novels such as The Financial Expert (1952), The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961), and The Vendor of Sweets (1967). The idiosyncratic, likeable characters in Narayan’s novels and the mythic town of Malgudi that he created as the setting of his major fiction are well known all over the world.

Prominent in the list of authors with major works of English fiction written in the 1960s and 1970s are Kamala Markandaya and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who was born in Germany but spent much of her adult life in India. Anita Desai became a powerful voice in the 1970s and 1980s. Her finely crafted novels explore the sensibilities of Indian men and women of the English-educated middle classes in the postcolonial era. In Clear Light of Day (1980) Desai portrays the relationship among siblings in a Delhi family against the background of partition. Desai’s In Custody (1984) is the story of a college lecturer seeking to meet a great poet who has been his hero since childhood.

In the postindependence era India has also produced a major body of poetry in English. Noteworthy among the modern Indian English poets are Nissim Ezekiel, Arun Kolatkar, Jayanta Mahapatra, and the female poet Kamala Das, who writes in Malayalam as well as English.

In 1980 Salman Rushdie published the novel Midnight’s Children. With this book, Rushdie became one of the first writers in English to employ magic realism. This technique, made famous by Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez in Cien años de soledad (1967; One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1970), blends fantasy and realism. The experience of moving with his family between India and Pakistan, and eventually emigrating to Britain, positioned Rushdie well to examine nationality in the late 20th century. Midnight’s Children is noted for its insights into issues of personal and national identity in India and Pakistan as postcolonial nations. Rushdie’s other works include Shame (1983), a novel about Pakistan, and The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), about the last surviving member of an Indian family that traces its lineage to the last Moorish sultan of Granada, Spain. Both works mix the fantastic and the realistic.

Rushdie’s work inspired an entire generation of young Indian writers to publish English novels that use innovative narrative strategies to explore the issues of national and transnational identity and history in an Indian context. Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English, August (1988) explores the cultural and political dilemmas of a young Indian bureaucrat. In his epic novel A Suitable Boy (1993), Vikram Seth traces the history of a family in a fictional town in postindependence India. Rohinton Mistry deals with the politics of class and communalism in A Fine Balance (1995).

One of the most ambitious and innovative members of this group of authors is Amitav Ghosh. His novel The Shadow Lines (1988) simultaneously traces the histories of two families, one Indian and one British, and exposes the senseless nature of the violence that accompanied the division of the Indian state of Bengal, leading to the formation of East Pakistan in 1947 and then of Bangladesh in 1971. The Shadow Lines questions the validity of all sorts of boundaries, national and international.

Arundhati Roy emerged as a literary figure in the late 1990s. In 1997 she won the Booker Prize, Britain’s highest literary award, for her novel The God of Small Things (1997), becoming the first Indian writer since Rushdie (with Midnight’s Children) to win the award. In the novel, her first, Roy’s masterful, original use of language, metaphor, and narrative evokes the experience of childhood in the Syrian Christian community in the South Indian state of Kerala.

Rushdie, Seth, Ghosh, and Roy are only a few of the many prominent Indian writers who have written powerful novels about living in a postcolonial world and who have gained attention on the world stage. The writings of these authors—with their innovative approaches, compelling drama, and masterful style—make Indian literature one of the most robust national literatures in the modern world.

0 Comments