Chalk on Elias’s Mind | Short Story by Danny Ballan

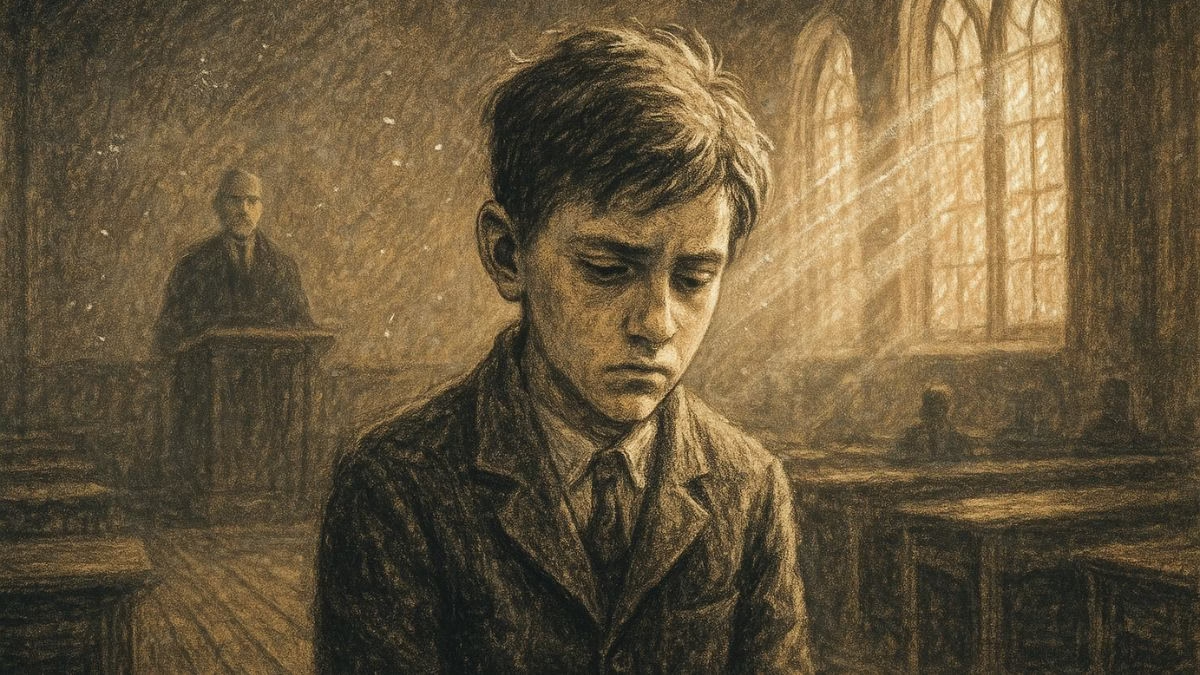

The chalk dust hung thick in the afternoon light slanting through the tall, arched windows of the assembly hall, catching stray sunbeams like miniature galaxies. The air smelled faintly of floor polish and damp wool coats. Elias, fifteen, kept his eyes fixed on the worn floorboards, the dark wood scarred by generations of shuffling feet. He meticulously traced the path of a single ant navigating the vast, polished terrain between his own scuffed shoes, a tiny, determined life in the face of overwhelming space. Headmaster Borodin’s voice, sharp and resonant as chipped flint, clipped the silence after each pronouncement. Each syllable was a small hammer blow against the expectant stillness, echoing slightly in the cavernous room. Elias felt the familiar tightening in his chest, a knot pulled taut whenever that voice commanded the room, a physical clench deep behind his ribs. He remembered the specific, electric sting of the ruler across his knuckles for an inkwell smudged just so – the dark blue stain blooming on the page like a forbidden flower, Borodin’s thin lips pressed into a line of profound disappointment before the swift, precise strike. He remembered the way the Headmaster’s gaze could pin you from across the hall, dissect you layer by layer, leaving you feeling not just small and wrong, but transparently inadequate. He’d rehearsed words in his head then, standing rigid in the rows of boys – sharp retorts like, “Was it truly necessary?” or “An accident deserves understanding, not punishment.” Questions that bordered on defiance, fueled by a burgeoning sense of injustice. But they always dissolved on his tongue, turning to hot ash before they could take shape, leaving only the bitter taste of silence. Fear was part of it, yes, the primal fear of authority embodied. But woven through it was the memory of his mother carefully darning a hole in his worn sock by the dim light of a single bulb, her brow furrowed with a worry he instinctively understood but couldn’t name. The Headmaster’s displeasure, a formal complaint, a whispered word in the village – it could have ripples Elias couldn’t afford to cause, waves that might swamp their precarious little boat. So, he’d learned to stare at the floor, to master the art of invisibility, to let the words wash over him, adding another layer, like sediment, to the quiet resentment hardening inside.

Years spun out like thread from a spool, pulling Elias further and further from the village. The scent of chalk dust and floor polish was replaced by the metallic tang of city air, the incessant rustle of papers, the deep, resonant hum of engines and ambition. He carried the weight of those silent assembly halls within him, not as a memory easily recalled, but as a shadow that sometimes flickered at the edges of his vision – a sudden tension in his shoulders during a tough negotiation, a flash of the Headmaster’s disapproving stare when confronted by bureaucratic indifference, a phantom echo of that voice in moments of quiet reflection that made him inexplicably angry. He wrestled with it, not always consciously. Sometimes it was burying himself in twelve-hour workdays, finding solace in the solvable problems of code and contracts. Other times it was a deliberate effort to stand taller, speak clearer, to occupy space in a way he never could as a boy. He built something new over the old, bruised foundations – a career forged in late nights fueled by lukewarm coffee and relentless focus, a confidence constructed brick by painstaking brick, each success a small refutation of the inadequacy instilled in him. Success arrived not as a sudden, blinding revelation, but as the slow, steady accumulation of respect earned, of financial ease that felt both liberating and slightly unreal, of a life shaped, finally, by his own hands, answering to no one’s arbitrary judgments.

The return was deliberate, meticulously planned. The car, sleek and silent, purred along the familiar, winding road back towards the village, its leather seats a world away from the splintered wood benches of the rattling, fume-choked bus he’d gratefully escaped on all those years ago. The landscape shifted from urban sprawl to rolling hills, the air growing cleaner, carrying the scent of damp earth and pine – smells that tugged at memories he’d thought long buried. He felt the old knot tighten in his chest, but this time it was different – coiled, purposeful, humming with a nervous energy he identified as anticipation. He had imagined this moment, played it out in the private theatre of his mind countless times across sleepless nights and long commutes: the confident walk up the familiar path, the carefully chosen, sharp words he’d finally unleash – words about the casual cruelty, the stifling of spirit, the lasting impact of fear. He envisioned the satisfaction, sharp and clean, of seeing that unflinching, judgmental gaze finally falter, forced to acknowledge the boy he was and the man he had become, standing before him not as a supplicant, but as an equal, perhaps even a superior.

He parked not outside the imposing gates of the school, but further down the lane, near the Headmaster’s small, stone house. Ivy crept thick over the walls, its green embrace interspersed with patches of withered, brown leaves, like age spots on the weathered stone. A few roof tiles looked loose; the garden was a tangle of weeds choking out neglected rose bushes. The gate, paint peeling, groaned open under his touch, the sound loud in the heavy afternoon quiet. He walked up the path, his expensive leather shoes crunching softly on the unkempt gravel, each step measured, deliberate. He paused at the door, noticing the faded paint and the tarnished brass knocker. He took a breath, feeling the thump of his own heart against his ribs, running the first few lines of his planned speech through his mind one last time. Then, he raised his hand, the cool wood solid beneath his knuckles, and knocked.

The door opened slowly, inch by reluctant inch, revealing not the imposing, ramrod-straight figure of his memory, but a man stooped and impossibly frail, leaning heavily on a worn, dark wooden cane. The hand gripping the cane’s handle was knotted with swollen knuckles, and it trembled slightly, a constant, minute vibration. The eyes that lifted to meet his still held a recognizable spark of the old steel, the familiar, assessing sharpness that had once terrified him, but they were clouded now, swimming behind thick lenses in a deep web of wrinkles like cracked parchment. Headmaster Borodin seemed smaller, diminished, his shoulders slumped inside a loose, grey cardigan, as if the years had physically ground him down, stealing his height and his certainty. He made a shuffling, uncertain movement, a soft grunt escaping his lips as he tried to step back to allow Elias entry, his balance suddenly, frighteningly precarious.

Elias stood frozen for a heartbeat, the air thick with the scent of dust and something vaguely medicinal, like old bandages, emanating from the shadowed interior of the house. The carefully rehearsed speeches, the catalogue of grievances, the biting accusations honed over years, the planned, triumphant display of his own hard-won power – they felt suddenly hollow, absurdly theatrical, like lines learned for a play whose stage had unexpectedly crumbled. The visceral memory of the ruler’s sharp impact, the echo of that commanding voice, the chilling grip of fear – it was all undeniably there, a phantom limb still aching with remembered pain. But standing before him was not the symbol of oppression he had come to confront, but simply an old man, struggling against gravity, against the simple, essential act of standing upright without falling.

A tremor ran visibly through Borodin’s thin arm as he listed sideways, his grip tightening desperately on the cane that threatened to slip on the worn threshold. The rehearsed anger, the carefully constructed words, all seemed to evaporate in that instant. Without conscious thought, Elias stepped forward. His hand moved not to strike or gesture, but instinctively, to steady. He caught the old man’s thin, surprisingly light arm, the bones feeling sharp and brittle beneath the thin fabric of his cardigan.

Borodin looked up, startled, his breath catching in a shallow gasp. For a long moment, their eyes locked. No words were spoken, none seemed necessary. The immense weight of years, of unspoken resentments, of fear and authority, dominance and submission, and the slow, inevitable erosion of time, hung palpably in the space between them. In that shared gaze, heavy with the unsaid, something shifted deep within Elias. The old man’s eyes held a flicker not of surrender, perhaps not even of true recognition, but maybe a dawning, bewildered understanding. Elias saw the ghost of the formidable Headmaster, the architect of so much youthful anxiety, but superimposed over it, undeniable now, was the frail, vulnerable human being before him.

Gently, wordlessly, Elias helped Borodin regain his footing, ensuring the cane was planted firmly. The silence stretched, filled only by the distant, cheerful chirping of unseen birds and the old man’s slightly ragged breathing. Then, Elias slowly, deliberately withdrew his hand. He gave a single, almost imperceptible nod – a gesture acknowledging everything and nothing. He turned, his back straight, and walked away down the gravel path, the crunching of his shoes the only sound marking his departure. He left the unspoken words, the unacted vengeance, the entire anticipated confrontation behind him, like dust motes settling, unseen, in the quiet afternoon air. As he reached his car, the familiar knot in his chest hadn’t vanished entirely, but it had loosened, transformed into something else entirely – not triumph, not forgiveness, but the quiet, complex weight of a choice made. He drove away, leaving the village and its ghosts behind, the taste of unspoken words lingering on his tongue, a strange mix of regret and a hard-won, unexpected peace.

The Crucible

[ppp_patron_only level=10]

Hello everyone, and welcome to The Crucible. I’m Danny Ballan, the writer of the story. It feels a little strange and wonderful to be sitting here, talking to you like this. For those of you who are new, The Crucible is where we take one of my stories and put it under the microscope—we heat it up, see what elements it’s made of, and what remains when the fire dies down. It’s a space for us to get cozy, pull back the curtain, and talk about the nuts and bolts, the heart and soul, of a piece of fiction.

Today, we’re diving deep into a story that seems to have resonated with so many of you: “Chalk on Elias’s Mind.” I’ve been floored by the emails and messages about this one. It’s a quiet story, in a way, about a confrontation that never happens, about the ghosts we carry and the strange peace we sometimes find not in victory, but in letting go. So, grab a cup of tea or coffee, settle in, and let’s get started. We’re going to be talking about where the story came from, hearing directly from the characters themselves, unpacking the language, and even answering some of your fantastic questions. I’m so glad you’re here.

Author Confessional

So, the first question I always get asked, the one that’s at the heart of everything, is: where did this story come from? And the honest answer is, it didn’t come from one place. It was more like a slow crystallization of different thoughts and feelings. The initial spark, though, the very first image that came to my mind, was the chalk dust. I have this incredibly vivid sensory memory from my own school days of the way afternoon sun would hit the air in a classroom after a teacher had been writing on the blackboard. It wasn’t just dust; it was this magical, swirling universe of particles. It felt like the physical manifestation of knowledge, of ideas, of time passing. And it had a particular smell, mixed with floor polish and old books. That sensory memory was my anchor.

I started thinking about what that chalk dust represents. It’s easily wiped away, it’s temporary, but the lessons—and the scars—from that time are anything but. They get ground into you. That led me to the idea of a character who is still, in some way, covered in the metaphorical dust of his past. That’s how Elias started to form. He wasn’t a specific person I knew, but an amalgamation of a feeling I think is universal: the feeling of being small and powerless in the face of an authority figure who seems monolithic, infallible, and terrifying. We’ve all had a Headmaster Borodin in our lives, haven’t we? A teacher, a boss, a coach, someone whose disapproval felt like a physical blow.

The central “what if” question that drove the plot was: What if you could go back? What if, after years of building yourself up, of forging your own power and success, you could finally confront that person? The fantasy of that moment is so potent. We imagine ourselves delivering the perfect, cutting speech, the one we couldn’t articulate when we were fifteen. We imagine them finally seeing us, acknowledging our strength, maybe even admitting they were wrong. It’s a revenge fantasy, pure and simple. And I wanted to explore that fantasy, but then I wanted to subvert it. I wanted to ask a follow-up question: What if, when you finally get there, the reality of the situation makes your perfect revenge completely meaningless?

In terms of choices I almost made… oh, there were a few. I wrote an entire version of the ending where the confrontation actually happens. Elias walks in, Borodin is still formidable, though older, and they have this tense, verbal sparring match. Elias lays out all his grievances, talking about the ruler, the fear, the stifling of creativity. And Borodin, in that version, doesn’t apologize. He defends his methods, saying he was forging strong men out of weak boys, that the world is a cruel place and he was preparing them for it. It was dramatic, sure, but it felt… cheap. It felt like a movie, not like life. It gave Elias a hollow victory that didn’t resolve the real, internal conflict. The knot in his chest wouldn’t have been loosened; it would have just been pulled into a different shape. So I scrapped about five pages of dialogue. It was painful, but it was the right call. The power of the story, I realized, wasn’t in the words that were said, but in the words that weren’t.

There was also a brief moment where I considered giving Elias a companion on his trip back—a wife, or a friend—someone he could talk to about his plan. I thought it might be a good way to externalize his inner monologue. But that felt wrong, too. This was a pilgrimage he had to make alone. The silence in the car on the way there is a crucial part of his mental preparation. It’s a journey into his own past, and you can’t bring anyone else with you on that trip. It had to be just him and his ghosts.

My writing process for this was a bit like archeology. I had the endpoint—the non-confrontation at the door—and I had the beginning—the memory of the chalk dust. The work was in carefully digging out the emotional layers in between. The biggest challenge was calibrating Elias’s motivation. I didn’t want his resentment to feel petty. It had to be profound, something that had genuinely shaped the architecture of his adult personality. The breakthrough came when I added the memory of his mother darning his sock. That single image, I hope, elevates his fear from simple cowardice to a complex, love-driven calculus. He wasn’t just afraid for himself; he was afraid for his family, for the precarious little boat they were in. That added a layer of nobility to his childhood silence and made his adult desire for confrontation feel that much more earned. The story really clicked into place for me once I understood that his silence was a form of protection, a sacrifice. And the final scene, then, becomes another form of sacrifice—the sacrificing of his own need for revenge for a more complicated, quieter form of peace.

Character Confessionals

Elias

I’m driving. It’s been a few hours since I left the village. The city lights are starting to smear across the horizon. The car is quiet. It’s the kind of quiet I paid a lot of money for. Engineered silence. It’s funny… all my life, I’ve been chasing silence. First, it was the silence of invisibility in that assembly hall. The silence of not making ripples. Then, it was the silence of a library late at night, of an office after everyone else had gone home. The silence of focus. And now, this. The silence of a well-made machine.

I keep replaying it. The walk up the path. The groan of the gate. The feel of the door under my knuckles. I had the words. God, I had the words. I’d spent years polishing them. They were sharp. They were precise. I was going to be a surgeon, carefully dissecting the tyranny of his little kingdom. I wanted to see his eyes. I wanted to see that unflinching certainty finally flicker. I wanted him to see me. Not the boy who stared at the floor, but the man who owned the building that boy could have only dreamed of working in. I wanted to hand him my business card and watch him read the title on it. It sounds so childish now, doesn’t it? So pathetic. But it felt so important. It felt like the final brick in the wall of the man I’d built.

And then the door opened. And all my well-constructed architecture just… crumbled. It wasn’t the years that had diminished him. It was gravity. It was the simple, brutal physics of a body failing. He was just an old man trying not to fall over. My great enemy. My personal tyrant. Afraid of a slippery threshold.

Did he recognize me? I don’t think so. Not really. Maybe he saw a ghost of a hundred other boys he’d intimidated, a composite of all the fear he’d inspired. But he didn’t see Elias. And the strangest thing is, in that moment, I realized my entire speech, my entire reason for being there, was predicated on him seeing Elias. And the man who could see me, the man I needed to confront, didn’t exist anymore. He’d been eroded by time, leaving this frail husk behind.

Something I never told anyone… when I was about twelve, after a particularly humiliating dressing-down for a math problem I’d gotten wrong on the board, I did something. I waited until after school. I snuck back to his classroom. He had this prized porcelain inkwell on his desk, a gift from some former student. I had a marble in my pocket. I was going to break it. I stood there for what felt like an hour, my heart hammering, the marble slick with sweat in my palm. I was going to do it. A small act of rebellion. But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. The fear he’d instilled was so deep it was like a part of my bones. I just put the marble on his desk, right in the center, and ran. He never mentioned it. I don’t know if he even noticed. But for years, I hated myself for that cowardice.

Today… when I reached out and steadied his arm… it felt like the opposite of that moment. My hand moved without my permission, not to break something, but to hold it up. The bones in his arm felt like a bird’s wing. So fragile. And the knot in my chest, that old friend… it’s still there. But it’s different. It’s not the tight, angry knot of resentment anymore. It’s looser. It feels more like… a scar. A place that was once wounded but has healed over. It still pulls sometimes, reminds me it’s there. But it doesn’t hurt. It’s just a part of me.

I didn’t get my confrontation. I didn’t get my victory. But driving away, I feel… lighter. As if all the words I was carrying, all that weight, I just left them on his doorstep. And I think, maybe, that’s a different kind of victory. The kind you don’t plan for. The kind that happens in the silence, when you choose not to speak.

Headmaster Borodin

The door. Someone at the door. It’s an effort, these days. Everything is an effort. The world seems to be getting further away. My own feet, a long and treacherous journey from my chair. The garden… a jungle. I remember when every rose bush was pruned just so. Precision. That’s what matters. Without precision, there is chaos. An ink smudge. A miscalculation. A shuffling foot. These are the seeds of chaos. You must stamp them out. You must be vigilant.

A man was at the door. Well-dressed. Expensive shoes. He had the look of the city about him. Soft hands, I’d wager. But his eyes… I knew the eyes. I’ve seen those eyes for fifty years. They’re the eyes of a boy who thinks he’s become a man, who has come back to prove something. To prove that he has escaped. I don’t remember his name. The names fade. They run together like watercolor in the rain. But the eyes, I remember. The flicker of fear, buried deep under layers of tailored wool and success. It’s always there. They think they’ve buried it, but it’s the foundation they’ve built everything on top of.

He stood there, ready to speak. I could see the words coiled behind his teeth. He had a speech prepared. They always do. They come back thinking they’re going to be the one. The one to finally tell me off. To list my sins. As if I don’t know what they say about me in the village. Borodin the Tyrant. Borodin the Cruel. They say it in whispers, but I hear it. I’ve always heard it.

What they don’t understand is that I was their crucible. I was the fire that burned away the weakness, the imprecision, the sentimentality. This world is not a gentle place. It does not reward excuses or pretty little flowers of ink on a page. It rewards strength. It rewards discipline. It rewards the man who can stand straight while others slouch. I gave them that. I gave them a spine. They may hate me for it, but their straight backs are my legacy. That man at the door, with his fancy car and his sharp suit… I helped build him. The fear I gave him was a gift. It was a whetstone. He sharpened his ambition on it. He should have thanked me.

Then my balance… this damnable leg. The world tilted. For a moment, just a moment, everything went grey. I thought, this is it, you old fool. You’re going to fall in front of one of them. The ultimate indignity. And then his hand was on my arm. It was firm. Gentle. He held me up. He didn’t speak. All those words he had saved up, and he said nothing. He just held my arm, steadying me.

He looked at me. And I looked at him. And for a second, I felt… tired. So incredibly tired. The weight of fifty years of being the rock, the flint, the unbending rule. Sometimes, in the quiet of this house, I wonder. Did I enjoy it? The fear in their eyes? A part of me… a part of me that I do not speak of… savored the absolute silence that would fall when I entered a room. It was a confirmation of order. Of control. My wife, before she passed, she used to say, “Alastair, the world can’t be arranged as neatly as your desk.” She never understood. The desk was the goal. The desk was the ideal.

He left. Just a nod. He walked away. I don’t feel victorious. I don’t feel defeated. I feel… observed. Like he saw right through the cardigan and the weak leg and the cloudy eyes and saw the whole damn thing. The man I was, the man I am. And he said nothing. Of all the boys who have dreamed of telling me off, he’s the one I might remember. The one who won, not by speaking, but by seeing. And by leaving me alone in the quiet.

Thematic & Literary Deep Dive

Alright, let’s talk about what this story is really about, beyond just the plot. When you strip it all down, “Chalk on Elias’s Mind” is a story about the collision between memory and reality. It’s about the way we build people up in our minds, especially people from our past, into these huge, symbolic figures. For Elias, Headmaster Borodin isn’t just a man; he’s the living embodiment of his childhood fear, his feelings of inadequacy, the architect of his anxieties. He’s this monolithic statue in the museum of Elias’s memory. The entire story is a journey towards confronting that statue. And the climax, the core theme, is the discovery that the statue has crumbled. It’s just an old man made of flesh and bone.

This ties into a central theme of power. The story explores how power dynamics shift, not just between people, but within ourselves. As a boy, Elias has no power. Borodin has all of it. As an adult, Elias has acquired all the traditional markers of power: wealth, success, a luxury car. He thinks he’s going back to demonstrate this power, to level the playing field, or even tilt it in his favor. He wants to use his newfound power to retroactively “win” the battles he lost as a child. But the real shift in power comes in that final moment. Elias discovers a new kind of power he didn’t even know he was looking for: the power to choose grace over grievance. The power to walk away. It’s a much quieter, more internal, and ultimately, I think, a more profound form of power than the one he came to display.

There’s also the theme of confrontation versus resolution. We’re so often taught, through movies and books, that resolution comes from a big, cathartic confrontation. The hero punches the villain. The lovers have the big, screaming argument and then kiss. The protagonist delivers the triumphant speech. I wanted to deliberately play with that expectation. Elias craves that confrontation, and so do we, as readers. We’re leaning in, waiting for the fireworks. When they don’t happen, there’s a moment of… is that it? But hopefully, that’s followed by a deeper sense of resolution. The problem wasn’t Borodin, the man. The problem was the weight of Borodin in Elias’s mind. And by choosing not to speak, by seeing the frail human being and acting with a simple, human instinct, Elias doesn’t defeat Borodin. He dissolves him. He lets the ghost go. The resolution is internal, not external.

In terms of symbols, we have a few key ones. The chalk dust is the most obvious, right there in the title. It represents the past—it hangs in the air, it gets on everything, it’s hard to wash off completely. It’s ephemeral, yet pervasive. It’s the residue of his education, both the academic and the emotional. The scarred floorboards in the assembly hall are another. They’re a physical record of all the boys who came before, all the shuffling, nervous feet. They represent a shared history of anxiety, a legacy of intimidation that Elias is just one part of. And then you have the contrast between Elias’s sleek, silent car and the rattling bus of his memory. It’s a very clear symbol of his journey, of his upward mobility and his escape. But what’s interesting is that the sleek car takes him right back to the source of his trauma. It shows that no matter how much external success you achieve, you can’t outrun the ghosts of your past. You have to turn the car around and face them. Finally, Borodin’s house, with its creeping ivy, peeling paint, and tangled garden, is a direct mirror of Borodin himself. The formidable, imposing structure of Elias’s memory is now decaying, being reclaimed by nature and time, its former order collapsing into chaos.

As for the structure, it’s a fairly classic triptych: Past, Present, and the Convergence of the two. The first part firmly establishes the trauma and the stakes through flashbacks. The second part establishes the man Elias has become, showing us the “armor” he has built. The third part brings the armored man back to the source of the trauma. The narrative device I leaned on most heavily is the limited third-person perspective. We are locked inside Elias’s head. We feel his anxiety, we see Borodin through his terrified child’s eyes, and we experience his shock and reassessment at the doorway. This is crucial. If we had Borodin’s point of view earlier, it would ruin the reveal. The whole story relies on us, the reader, sharing Elias’s perception of Borodin as a monster, only to have that perception shattered along with his in the final scene. The story is as much about the deconstruction of a memory as it is about the events themselves.

Key Vocabulary & Language Craft

I’m a firm believer that stories are built not just from plot and character, but from the very texture of the words themselves. The specific choices you make can change the entire mood of a scene. So, I thought it would be fun to pull out a few phrases from the story and talk about why I chose them.

Let’s start with a description of Headmaster Borodin’s voice: “sharp and resonant as chipped flint.” I could have just said his voice was “sharp” or “harsh.” But “chipped flint” does a few things. First, flint is a type of rock. It’s hard, it’s old, it’s unyielding—all qualities of Borodin’s character. Second, the word chipped suggests something that has been broken off, something with a sharp, dangerous edge. It’s not a smooth, polished stone; it’s a weapon. A piece of flint can be used to create a spark, to start a fire. Borodin’s voice can spark fear, or shame, or a sudden, hot flush of anger. It has a primitive, elemental quality to it. So that one little phrase is trying to pack in ideas of hardness, danger, and a kind of ancient, unforgiving power.

Next, there’s the description of the ink smudge on Elias’s page: “the dark blue stain blooming on the page like a forbidden flower.” Again, I could have said “a big ink stain.” But the word blooming gives it a sense of life, of something organic and uncontrollable, which is the opposite of the rigid order Borodin demands. And a flower is usually something beautiful, something to be admired. By calling it a “forbidden flower,” I’m trying to create a tension. It frames the ink smudge not just as a mistake, but as an act of unintentional, rebellious beauty in a world that has no place for it. It hints at the creative spirit that the Headmaster is trying to crush. It’s a small tragedy on the page—a moment of accidental artistry that is met not with understanding, but with punishment.

How about the description of Borodin’s wrinkles in the final scene? “a deep web of wrinkles like cracked parchment.” This is a fairly common type of metaphor, but I chose it for a specific reason. Parchment is something you write on. It carries history, stories, laws. Borodin’s face has literally become a record of his life, a historical document. But it’s cracked parchment. It’s dry, fragile, and falling apart. The history it holds is becoming illegible, brittle. It suggests that the authority and the laws he once wrote on the lives of his students are now as fragile as his own skin. The “web” also suggests something that can trap, which connects back to the feeling of being trapped by his gaze that Elias remembers so vividly.

Here’s another one I really thought about: the feeling in Elias’s chest. In the beginning, it’s a “familiar tightening in his chest, a knot pulled taut.” Later, when he returns, it’s “coiled, purposeful, humming with a nervous energy.” And at the very end, it “hadn’t vanished entirely, but it had loosened, transformed.” I wanted to track Elias’s emotional journey through this physical sensation. It’s the same knot, the same location of trauma in his body, but its quality changes. At first, it’s a passive thing, a knot being pulled taut by an outside force (Borodin). In the middle, it’s active, coiled like a snake, full of his own purpose and energy. He has taken ownership of the feeling. And by the end, it’s neither. It’s not gone, because trauma doesn’t just disappear, but it has loosened. It’s no longer a source of pain or motivation, but simply a part of his personal landscape. Using this recurring physical metaphor, this “knot,” was my way of charting his internal transformation without having to explicitly state, “Elias felt differently now.”

Finally, the very last line, describing the taste on his tongue: “a strange mix of regret and a hard-won, unexpected peace.” This was so important to me. I didn’t want the ending to feel simple. It’s not pure peace. It’s not a Hollywood “happily ever after.” There is a sense of regret. Regret for the words he never got to say, for the victory he’d imagined, maybe even a strange, empathetic regret for the frail man Borodin had become. But mixed with that is peace. And it’s a hard-won peace. It’s a peace he had to travel all that way and go through that entire emotional crucible to find. And it’s unexpected. It’s not the peace he came for, but it’s the peace he found. And for me, that combination of conflicting but honest emotions felt much more true to life than any simple, clean resolution.

Fan Engagement

This is one of my favorite parts of the process—getting to hear from all of you. The story doesn’t really feel complete until it’s living in a reader’s mind. I’ve gotten some incredible questions from my advanced readers group for “Chalk on Elias’s Mind,” and I wanted to share and respond to a few of them here.

Our first one comes from Sarah in Toronto. Sarah writes:

“Hi Danny, thank you for this story. It felt incredibly real. My question is about Headmaster Borodin. I found myself fluctuating between hating him and feeling a bit sorry for him at the end. In your mind, was he a true sadist who enjoyed the power he had over these boys, or did he genuinely believe his cruel methods were for their own good?”

That is the million-dollar question, Sarah, and thank you for asking it. I deliberately tried to leave it a little ambiguous in the story itself, but in my own mind, the answer is: both. I don’t think Borodin is a one-dimensional villain. I don’t believe he woke up in the morning thinking, “How can I be evil today?” I genuinely think he operated from a belief system, probably forged in an even harsher past of his own, that the world is an unforgiving place and that his duty was to make his boys hard enough to survive it. He would see his methods not as cruelty, but as a necessary, painful forging process, like a blacksmith beating soft iron into a strong blade. He would have called it “character building.”

However—and this is the crucial part—I think he absolutely developed a taste for the power it gave him. He became addicted to the fear he inspired, not because he was sadistic in a cartoonish way, but because that fear was proof that his system was working. The silence in the hall, the downcast eyes, the rigid postures—these were all affirmations of his control, his order, in a chaotic world. So, while his core motivation might have started from a place of warped good intentions, it became corrupted over time by the profound satisfaction he got from wielding absolute power. He’s a tragic figure, in a way. A man who became a prisoner of his own ideology.

Next, we have a comment from Mike in London. Mike has a bit of a different take. He says:

“Danny, great story. I have to be honest, though, I felt a little let down by the ending. My interpretation is that Elias didn’t really win. He saw that Borodin was old and weak, and he just chickened out. The story says the knot is still there, so he didn’t really resolve anything. He just ran away again, same as he did as a boy. Am I wrong?”

Mike, first of all, you are never “wrong” in an interpretation. If that’s how the story felt to you, then that is a valid and powerful reading of it. And I love this take because it forces me to defend the ending, which is a great exercise. I can absolutely see why you’d feel that way. On the surface, he did not accomplish the mission he set out for himself. He rehearsed the words and never said them.

But I would argue that he didn’t run away; he rose above. His childhood response was driven by fear. His adult choice, however, is driven by something more complex: a mixture of pity, understanding, and a sudden, shocking re-evaluation of what victory even means. To deliver his crushing speech to that frail, old man wouldn’t have been a display of strength; it would have been an act of bullying. It would have made Elias a new version of Borodin. The ultimate victory, the thing that truly proves he has become a better man, is his ability to see the pathetic reality of the situation and choose not to inflict more pain. He breaks the cycle. The fact that the knot is still there is key. I didn’t want to suggest that a single moment can magically erase decades of trauma. That would be dishonest. The resolution isn’t the erasure of the wound; it’s the decision to stop picking at the scab. It’s a quieter, more mature victory, but in my eyes, it’s a victory nonetheless.

Here’s one from Amira in Beirut, which touches on a character who is barely there but is so important. Amira writes:

“I loved the brief mention of Elias’s mother darning his sock. It was such a small detail, but it felt like the whole emotional core of his childhood. Was his ambition and his drive to succeed really about proving Borodin wrong, or was it more about making sure his own family would never be in that ‘precarious little boat’ again?”

Amira, you absolutely nailed it. Thank you. That is 100% the emotional engine of the story for me. Borodin is the antagonist, the mountain Elias feels he must conquer. But his mother is his heart. She represents the why. The rage against Borodin is the fuel, but the love and protective instinct for his mother is the destination. He doesn’t want power for its own sake. He wants security. He wants the kind of stability where a single complaint from a Headmaster can’t threaten his family’s world. His ambition isn’t just a reaction to negative stimulus (Borodin’s cruelty); it’s a proactive drive toward a positive goal (his mother’s peace of mind). In a way, the whole story is a silent tribute to her. His success, his car, his confidence—they are all part of the fortress he built to protect the memory of that quiet, worried woman darning a sock. That’s why adding her to the story was the big breakthrough for me. She grounded his motivation in love, not just in hatred.

Finally, a question from David in Chicago:

“Why chalk? The title is ‘Chalk on Elias’s Mind,’ not ‘Borodin on Elias’s Mind.’ What is it about the chalk itself that you found so central to the story?”

Great question, David. For me, the chalk is the perfect metaphor for this kind of memory. Think about what chalk is. It’s a tool for teaching, for making things clear and explicit on a blackboard. But it’s also dusty, messy, and impermanent. A swipe of an eraser, and the lesson is gone. But the dust settles everywhere. It gets on your hands, your clothes, in the air you breathe. That, to me, is exactly what this kind of formative experience is like. The specific incidents—the ruler, the scolding—are like the words on the board. They might fade over time. But the residue, the emotional “chalk dust,” settles deep inside you. It becomes part of your mental atmosphere. Elias has spent his whole life trying to succeed, to build a clean, sleek, modern life, but he can’t quite get rid of that fine layer of dust from his past. The title suggests that it’s not just the man he’s haunted by, but the entire environment, the very air of that time, and chalk is the most tangible symbol of that environment.

Thank you all for these incredible questions. It’s a privilege to know the story is in such thoughtful hands.

And that brings us to the end of this episode of The Crucible. Thank you so much for joining me today, for letting me peel back the layers of “Chalk on Elias’s Mind.” It’s a strange thing, to talk so much about something that came out of silence, but it’s been a real pleasure to share its origins and secrets with you.

These stories, once they’re written, belong to you, the reader, as much as they do to me. Your interpretations, your connections, your feelings—they are what give the words life beyond the page. So please, keep them coming.

Until next time, be well, read well, and thank you for listening.

[/ppp_patron_only]

0 Comments