- Audio Article

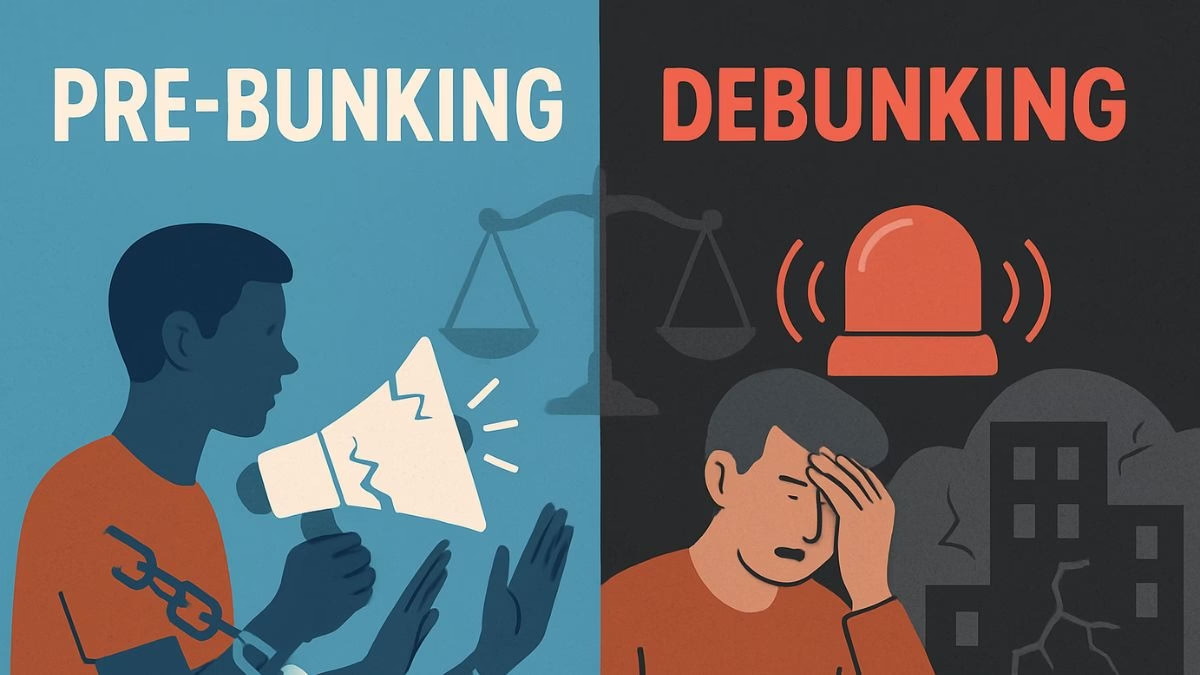

- The Sisyphean Task of Cleaning the Internet

- The Science of the Mental Vaccine: Inoculation Theory 101

- Pre-bunking in the Wild: Games, Videos, and Building Resilience

- The Road Ahead: Challenges and the Future of Inoculation

- From Helpless Victims to Empowered Skeptics

- MagTalk Discussion

- Vocabulary and Speaking

- Grammar and Writing

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

Audio Article

The Sisyphean Task of Cleaning the Internet

For the last decade, we have been locked in an exhausting, seemingly endless war against lies. We’ve built armies of fact-checkers, designed elaborate content moderation systems, and played a global game of whack-a-mole with viral falsehoods. This reactive approach, known as “de-bunking,” is the digital equivalent of cleaning up after a toxic spill. It’s noble, it’s necessary, but it’s also a fundamentally losing battle. A lie, as the saying goes, is halfway around the world before the truth has its boots on. By the time a fact-check is published, the lie has already infected millions of minds, hardened beliefs, and done its corrosive work on public trust. It’s a Sisyphean task, pushing the boulder of truth up the hill each day, only to watch it roll back down under an avalanche of new falsehoods.

But what if we’ve been fighting the wrong war? What if, instead of focusing all our energy on cleaning up the spill, we could give people the mental equivalent of a hazmat suit before they encounter the toxin? This is the core idea behind a proactive, psychologically-grounded strategy that is rapidly gaining traction among researchers and tech platforms: psychological inoculation, or “pre-bunking.” The concept is as simple as it is profound. Instead of refuting a specific lie after it has spread, pre-bunking exposes people to a weakened dose of a misinformation tactic—the underlying trickery and logical fallacies used to make lies persuasive—before they encounter it in the wild.

This article is an exploration of that elegant, hopeful idea. We will delve into the surprisingly old science of “inoculation theory” to understand why this mental vaccination works. We will then journey to the front lines of this new fight, showcasing the innovative online games and clever video campaigns that have been successfully used to build cognitive immunity against manipulation on a massive scale. It’s a story not about playing defense, but about building a resilient offense. It’s about switching from a strategy of cure to one of prevention.

The Science of the Mental Vaccine: Inoculation Theory 101

The idea of inoculating minds against persuasion isn’t new. It didn’t emerge from a Silicon Valley think tank but from the world of social psychology in the Cold War era. In the early 1960s, a researcher named William McGuire, curious about how to make beliefs more resistant to attack, looked to biology for a metaphor.

A Weakened Dose of the Virus

McGuire’s logic was intuitive. A medical vaccine works by introducing a weakened or dead version of a virus into the body. This pathogen is too weak to cause a full-blown illness, but it’s strong enough to trigger the immune system. The body recognizes the threat, figures out how to fight it, and produces antibodies. Later, when the real, full-strength virus comes along, the body is already prepared. The antibodies are there, the defenses are up, and the infection is neutralized.

McGuire theorized that the same process could work for our beliefs. If you want to strengthen someone’s conviction, you don’t just surround them with arguments that support it. That, he argued, is like raising a child in a sterile, germ-free bubble. The moment they step into the real world and encounter a real germ, they get sick. Similarly, a belief that has never been challenged is fragile. The moment it’s confronted with a clever counter-argument, it can crumble.

The solution? Inoculation. McGuire’s classic experiments worked like this: first, you state a belief (e.g., “It’s important to brush your teeth daily”). Second, you issue a warning that this belief might be challenged. This is the “threat” component that kicks the cognitive immune system into gear. Third, and this is the crucial step, you present a “weakened dose” of the attack—a flimsy, easily refutable argument against the belief (e.g., “Brushing your teeth is bad because some studies show it can wear down enamel”). Finally, you immediately help the person dismantle that weak argument, showing them exactly why it’s a poor or misleading line of reasoning. This is the “refutational pre-emption” or pre-bunk.

The result is a kind of cognitive antibody. The person has now been exposed to the threat, has practiced defending against it, and is mentally prepared for future, more potent attacks.

From Brushing Teeth to Disinformation Tactics

For decades, inoculation theory was a fascinating but somewhat niche area of study. The infodemic changed all that. Researchers realized that in the chaotic online world, debunking every single lie was impossible. There were just too many. But the tactics used to spread those lies? They were surprisingly limited and repetitive.

Dr. Sander van der Linden, a social psychologist at the University of Cambridge and a leading figure in modern inoculation research, puts it this way: “Misinformation is like a magician’s act. While the magician might have a hundred different tricks, they’re all based on a handful of core principles of misdirection and illusion. If you teach the audience how the principle of misdirection works, they won’t be fooled by any of the hundred tricks.”

This insight was a game-changer. Instead of trying to fact-check the claim that “Vaccine X contains microchips,” you could pre-bunk the manipulative tactic being used: the conspiracy theory itself. Instead of refuting a specific fake celebrity endorsement, you could pre-bunk the tactic of emotional manipulation. This “tactic-based” inoculation is a universal vaccine. It doesn’t just protect you against one viral strain; it builds a broad-based resistance to the very methods of manipulation, regardless of the topic.

Pre-bunking in the Wild: Games, Videos, and Building Resilience

The theory is elegant, but does it work in the real world, outside of a controlled lab? The answer, increasingly, is a resounding yes. A new generation of researchers, in collaboration with tech companies like Google and Meta, have been developing and deploying inoculation interventions at a massive scale, with remarkable results.

The Bad News Game: Learning to Think Like a Tyrant

One of the most successful and well-known examples is an online game called Bad News. Developed by van der Linden and a team of Dutch researchers, the game playfully subverts the user’s role. Instead of being a passive consumer of news, you are cast as a budding disinformation tycoon. Your goal is to gain as many followers as possible by deploying the common tactics of the trade.

The game walks you through six key strategies: impersonation (pretending to be someone else), emotion (using fear and outrage), polarization (pitting groups against each other), conspiracy (weaving elaborate narratives), discrediting (attacking opponents), and trolling. As you choose to use these tactics in a simulated social media feed, you earn badges and followers, but you’re also learning, from the inside out, how these manipulative techniques work. You’re not just told that emotional content is manipulative; you actively choose to post an outrage-baiting headline and see the (fake) followers roll in.

It’s a classic inoculation: a weakened, gamified dose of the poison. And studies have shown it’s incredibly effective. People who play the game become significantly better at spotting manipulative tactics in real-world news articles and social media posts, and they become less likely to share fake news. The “cognitive antibodies” they develop in the safe, simulated environment of the game transfer to the chaotic real world.

YouTube’s 90-Second Shields

While games are a powerful tool, they require users to actively seek them out and spend time playing them. A more recent innovation is the “attitudinal inoculation” video campaign, pioneered by researchers at Google and Cambridge University. The goal here is to deliver the vaccine in a format people are already consuming: short online videos.

The team created a series of slick, animated 90-second videos, each designed to pre-bunk a specific manipulation technique. One video explains the concept of a “false dilemma,” where an argument is dishonestly framed as an either/or choice. Another explains “scapegoating,” the tactic of blaming a complex problem on one specific group.

These videos were then run as pre-roll ads on YouTube, targeting users in specific countries. They don’t mention any specific conspiracy or political issue. They just arm the viewer with the knowledge of the tactic itself, presented in a simple, memorable way. Large-scale studies involving millions of users have found that even this brief, passive exposure significantly boosts people’s ability to recognize the manipulation technique and their confidence in being able to spot it again. It’s a mass-vaccination campaign for the mind, delivered directly into the digital bloodstream.

The Road Ahead: Challenges and the Future of Inoculation

Pre-bunking is not a silver bullet. The fight against misinformation is too complex for any single solution. But it represents a vital and powerful shift in our approach, from a reactive posture of defense to a proactive strategy of building resilience.

The Limits of the Vaccine

Several challenges remain. One is the question of dosage and boosters. How long does the inoculation effect last? Research suggests the cognitive antibodies can fade over time, meaning people might need periodic “booster shots” to maintain their immunity.

Another challenge is reaching the right people. Inoculation tends to work best on those who aren’t already deeply entrenched in a conspiratorial worldview. For individuals who have made a particular conspiracy a core part of their identity, a simple pre-bunking video is unlikely to break through. It’s a vaccine, not a cure for an advanced-stage infection.

Finally, there’s the question of the evolving virus. As manipulators become aware that the public is being inoculated against their old tricks, they will inevitably develop new ones. This means the pre-bunking effort must be a continuous process of research and adaptation, identifying new manipulation “variants” as they emerge and developing new inoculation materials to counter them.

From Helpless Victims to Empowered Skeptics

For too long, the narrative around misinformation has cast the public as helpless victims, passively duped by powerful algorithms and nefarious actors. De-bunking, for all its good intentions, often reinforces this frame: the experts arrive after the fact to tell the public what they should have believed.

Pre-bunking flips the script. It is an empowering strategy that treats people not as victims to be rescued, but as active participants in their own cognitive defense. It doesn’t tell you what to think; it gives you the tools to think critically about how you are being persuaded. It builds a foundation of what researchers call “meta-cognition”—the ability to think about your own thinking processes.

By shifting our focus from refuting individual lies to exposing the universal tactics of deception, we can move beyond the endless, Sisyphean game of whack-a-mole. We can begin to build a population that is not just informed, but is resilient and resistant to manipulation. We cannot create a perfectly sterile, germ-free internet. But we can, it seems, vaccinate our minds. And in the ongoing battle for truth, a good vaccine is the best weapon we have.

MagTalk Discussion

Vocabulary and Speaking

Hey, let’s take a moment to really dig into some of the words and phrases we used in the article on pre-bunking. When you’re talking about ideas from psychology and communication, having the right vocabulary is like having the right set of tools. It lets you build a more precise and powerful argument. These aren’t just academic buzzwords; they’re concepts that can help you understand and describe the world of information around you.

Let’s start with the word proactive. We called pre-bunking a proactive strategy. To be proactive is to take action and cause change rather than just reacting to things that happen. It’s the opposite of being reactive. A reactive person waits for a problem to occur and then tries to fix it—that’s de-bunking. A proactive person anticipates a potential problem and takes steps to prevent it from ever happening—that’s pre-bunking. It’s a fantastic word that you can apply to almost any area of your life. For instance, in health, a reactive approach is going to the doctor when you’re sick; a proactive approach is exercising and eating well to stay healthy in the first place. At work, you could say, “Instead of just dealing with customer complaints as they come in, let’s be proactive and improve the product so the complaints don’t happen.” It’s a word that signals initiative, foresight, and control.

Next, we said the idea of pre-bunking is “gaining traction.” Traction, in this sense, doesn’t have to do with the grip of your car’s tires, though that’s where the metaphor comes from. When an idea, product, or movement gains traction, it means it’s becoming popular, accepted, or influential. It’s getting a grip on the public consciousness and starting to move forward. It’s that crucial phase where something goes from being a niche idea to something that people are really starting to pay attention to. You hear this a lot in the business world: “Our new app is finally starting to gain traction with users.” But you can use it for anything that’s growing in popularity. “The campaign for a new park in our neighborhood is really gaining traction.” It’s a great, dynamic way to say that an idea is taking hold and making progress.

The central metaphor of the article was the word inoculate. We talked about how pre-bunking can inoculate minds. The primary meaning, of course, is from medicine: to vaccinate someone to give them immunity to a disease. But we use it metaphorically to mean protecting someone from a harmful influence or opinion. It’s such a powerful metaphor because it brings with it the entire concept of a vaccine: a small, weakened dose to build up a defense. You’re not just protecting them; you’re doing it in a very specific, scientific way. You could use this metaphorically in other contexts, too. For example, a parent might say, “I try to inoculate my kids against the pressures of advertising by talking to them about how ads work.” Or, “The financial literacy course is designed to inoculate students against predatory loan schemes.” It implies a very deliberate, preventative form of protection.

Now for the other side of the coin: refute. Pre-bunking aims to avoid having to “refute a lie after it has spread.” To refute an argument or a statement is to prove that it is wrong or false. It’s a much stronger word than simply “deny” or “disagree with.” If you deny something, you’re just saying it’s not true. If you refute it, you’re bringing the receipts. You’re providing evidence and logical arguments to dismantle it completely. It’s a key word in formal debate, legal arguments, and scientific papers. For example, “The lawyer’s job was to refute the prosecutor’s claims with concrete evidence.” Or, “The new study refutes the old theory about the planet’s formation.” When you use the word refute, you are signaling a takedown based on evidence, not just opinion.

Let’s talk about fallacy. Pre-bunking often involves exposing people to logical fallacies. A fallacy is a mistaken belief, especially one based on an unsound argument. It’s a flaw in reasoning, a trick of logic that makes an argument seem more persuasive than it actually is. The article mentioned the “false dilemma,” which is a type of fallacy. Another common one is the “straw man” fallacy, where you misrepresent someone’s argument to make it easier to attack. Understanding fallacies is like being a building inspector for arguments; you learn how to spot the weak foundations. You could say, “His whole argument was based on a logical fallacy; he was confusing correlation with causation.” Or, “It’s a common fallacy that you have to be a ‘math person’ to learn how to code.” It’s a fantastic word for identifying faulty thinking.

Here’s a great adjective: potent. We talked about preparing people for more potent attacks. Potent simply means having great power, influence, or effect. It’s often used to describe things like medicine, chemicals, or arguments. A potent drug has a strong effect. A potent argument is very persuasive and difficult to argue against. It’s a step up from just “strong” or “powerful.” It implies a concentrated strength. For instance, “The CEO gave a potent speech that rallied the employees.” Or, “The smell of the spices was so potent it filled the entire house.” The lies we face online are often potent because they are crafted to appeal to our emotions in a very powerful way.

Let’s look at the word intuitive. We said William McGuire’s logic was intuitive. Something that is intuitive is easy to understand or operate without needing much thought or instruction. It’s something you feel is true or understand instinctively, using your intuition. A well-designed smartphone app is intuitive; you just know how to use it without reading a manual. The idea of psychological inoculation is intuitive because it maps so perfectly onto our existing understanding of how medical vaccines work. You could say, “The solution to the puzzle was not obvious, but it felt intuitive once I found it.” Or, “She has an intuitive understanding of people’s emotions.” It’s a word for that “gut feeling” kind of understanding.

Now for a word that describes the problem itself: endemic. While not in the final article, it’s a perfect word for the infodemic. In medicine, a disease is endemic when it is regularly found among particular people or in a certain area. Malaria is endemic to many tropical regions. Metaphorically, we use endemic to describe a problem or a quality that is widespread and deeply rooted in a particular place or society. “Corruption is endemic in the country’s political system.” Or, “Cynicism seems to be endemic among young people today.” To say that misinformation is endemic to the internet means it’s not just an occasional outbreak; it’s a constant, widespread feature of the environment.

Remember that poor guy from the Greek myths? The word for his task was Sisyphean. We described de-bunking as a Sisyphean task. Sisyphus was a king in Greek mythology who was condemned for eternity to roll a massive boulder up a hill, only to have it roll back down every time he neared the top. Therefore, a Sisyphean task is one that is endless, laborious, and ultimately futile or unavailing. It’s a wonderfully descriptive and slightly dramatic way to describe a task that you have to do over and over again without ever making real progress. “Trying to keep the house perfectly clean with three small children is a Sisyphean task.” Or, “He felt that arguing with his boss was a Sisyphean effort.” It perfectly captures the frustrating, repetitive nature of the old way of fighting misinformation.

Finally, let’s talk about the word cognitive. We talked about building cognitive immunity. Cognitive is an adjective that relates to cognition—the mental process of thinking, knowing, remembering, and understanding. It’s all about the mechanics of your mind. Cognitive psychology is the study of how we think. Cognitive dissonance is the mental stress from holding conflicting beliefs. When we talk about cognitive immunity, we’re specifically talking about immunity that exists in your thinking processes. It’s a more precise way of saying “mental immunity.” You can use it to specify that you’re talking about the thinking part of the brain. “The game is designed to improve children’s cognitive skills.” Or, “As we age, some of our cognitive abilities naturally decline.”

So there you have it. A toolkit of words to help you talk about these ideas with more precision and flair.

Now, for our speaking skill. Today, let’s focus on the art of the hook. The first few sentences you say are the most important. They determine whether your audience leans in, interested, or tunes out. In the article, we started not by defining pre-bunking, but by painting a picture of the “Sisyphean task” of de-bunking. It’s a hook. It uses a strong image and a shared frustration to grab the reader’s attention. A good hook can be a provocative question, a surprising statistic, a short, dramatic story, or a powerful metaphor.

Here’s your challenge: The next time you have to explain something important, whether it’s in a work meeting, a presentation, or even just a conversation with a friend, I want you to plan your opening sentence or two very carefully. Don’t just start with “So, today I’m going to talk about…” That’s boring. Try to create a hook. If you need to explain a new company policy, instead of starting with the policy, you could start with a question like, “What’s the single biggest source of frustration in our current workflow?” If you want to convince your friends to try a new restaurant, don’t start with the address. Start with, “I think I just had the best taco of my entire life.” Your mission is to consciously craft a compelling opening. Write it down, practice it. See if you can make your listener’s ears perk up in those first 15 seconds. It’s a skill that will make everything you say more impactful.

Grammar and Writing

Let’s shift our focus to the practical application of these ideas through writing. The article you read explains the concept of pre-bunking. Now, you get to become a pre-bunker yourself. The goal of a pre-bunking intervention is to communicate a potentially complex idea—a logical fallacy or a manipulation tactic—in a way that is clear, memorable, and empowering. This requires a specific kind of writing.

Here is your writing challenge:

Choose one of the following common manipulation tactics: 1) Scapegoating (blaming a complex problem on one group), 2) The False Dilemma (presenting only two choices when more exist), or 3) Ad Hominem (attacking the person instead of their argument). Your task is to create a short “pre-bunking script” of 400-600 words. This script could be for a short, animated YouTube video, a social media carousel post, or a mini-game. Your script should follow the core steps of inoculation: 1) Introduce the tactic and warn the reader about it. 2) Explain the tactic using a clear, simple, and relatable analogy or example. 3) Give the reader a final piece of advice on how to spot it and defend against it.

This is a fantastic exercise in clear, persuasive, and educational writing. To nail it, let’s focus on a few key grammatical and stylistic tools that are essential for this kind of instructional text.

First, let’s harness the power of the imperative mood. The imperative is the form of the verb used for giving commands, instructions, and advice. In English, it’s just the base form of the verb (e.g., Watch, Think, Look, Be). When you’re writing a pre-bunking script, you’re not just describing a concept; you are guiding your audience. The imperative mood is your best tool for this. It’s direct, clear, and creates a feeling of a coach or a helpful guide speaking directly to the reader.

Instead of saying, “It would be a good idea for people to be aware of this tactic,” you say, “Be aware of this tactic.”

Instead of, “One thing you could do is check the source,” you say, “Check the source.”

Look at how you could structure your script using imperatives:

The Warning: “Watch out for this next trick. Don’t let it fool you.”

The Explanation: “Imagine a situation where… Think of it like this…”

The Advice: “Ask yourself this question. Look for this specific pattern. Remember this rule.”

Using the imperative mood makes your writing feel active and empowering. You are giving your audience clear, actionable steps, which is exactly the point of pre-bunking.

Second, let’s focus on using analogies and simple metaphors for clarity. A logical fallacy can be an abstract concept. The fastest way to make it concrete and memorable is to connect it to something the reader already understands. This is the art of the analogy.

In our main article, we didn’t just talk about psychological inoculation; we anchored it to the powerful and intuitive metaphor of a medical vaccine. This does most of the explanatory work for us.

For your challenge, you need to create a simple analogy for your chosen fallacy:

For Scapegoating: You could use the analogy of a magician’s misdirection. “Imagine a magician waving his right hand wildly to get your attention. Why? Because the real trick is happening with his left hand. Scapegoating is a form of political misdirection. Look for the politician waving their hands and yelling about one group. Then, ask yourself: what’s the real problem they don’t want me to see?”

For a False Dilemma: You could use the analogy of a restaurant menu. “Imagine going to a restaurant where the waiter tells you that you can only order the salad or the steak. But you know they have a full kitchen. The waiter is giving you a false dilemma. Online, when you’re told ‘You’re either with us or against us,’ remember the menu. There are almost always more than two options.”

A good analogy is the secret weapon of instructional writing. It simplifies the complex without dumbing it down.

Finally, let’s work on structuring your text with clear signposting and transitional phrases. When you’re teaching someone a new concept, you need to lead them by the hand. Signposting language consists of words and phrases that signal to the reader what you’re doing and where you’re going. It’s like a verbal GPS for your argument.

Common signposting phrases include:

Introducing a topic: “First, let’s look at…”, “The first thing to understand is…”

Giving an example: “For instance…”, “A perfect example of this is…”

Contrasting ideas: “However…”, “On the other hand…”

Summarizing or concluding: “So, to sum up…”, “The key takeaway is…”, “In short…”

In your pre-bunking script, this structure is vital.

Start of Script: “Here’s a trick you’ll see all the time online.” (Introduces topic)

Middle of Script: “For example, imagine a politician says…” (Gives example). “On the surface, this sounds convincing. However, look closer.” (Contrasts ideas).

End of Script: “So, what’s the bottom line? When you see this tactic, just remember one thing.” (Summarizes and concludes).

These phrases make your script easy to follow. They break the information into digestible chunks and create a logical flow from the warning to the explanation to the solution.

So, to recap your mission for this writing challenge:

Use the imperative mood (e.g., Look, Ask, Remember) to give clear, direct instructions and advice.

Create a simple, intuitive analogy to explain your chosen fallacy in a concrete and memorable way.

Structure your script with clear signposting language to guide your reader effortlessly from beginning to end.

By mastering these techniques, you can write a script that doesn’t just inform but actually inoculates. You can build a piece of writing that is a tool for cognitive empowerment. Good luck.

Vocabulary Quiz

Let’s Discuss

Here are some questions to get you thinking more deeply about pre-bunking and the fight for a healthier information ecosystem. Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments section.

The article uses a medical metaphor (vaccines, inoculation, antibodies). Do you find this metaphor helpful or potentially problematic?

Does comparing misinformation to a “virus” risk framing people who fall for it as “sick” or “unclean”? On the other hand, does the metaphor of a “vaccine” effectively communicate the idea of proactive defense and building immunity? Discuss the power and potential pitfalls of using metaphors to explain complex social issues.

Think about a time you realized a piece of information was manipulative. What was the “tell”? Which specific tactic did you notice?

Was it an appeal to extreme emotion (fear or outrage)? Did it try to create a false dilemma (“if you’re not with us, you’re against us”)? Was it a classic scapegoating tactic? Share your own experience of spotting a manipulation tactic in the wild. How did it make you feel, and did it change how you consume information?

Who should be responsible for creating and distributing these “mental vaccines”? Should it be tech companies like Google and YouTube, governments, the education system, or non-profit organizations?

Consider the pros and cons of each. If a tech company does it, could they use it to subtly favor their own interests? If a government does it, could it be used as a form of propaganda to “inoculate” citizens against dissent? What role should schools play in building these “cognitive antibodies” from a young age?

The article mentions that pre-bunking may be less effective on people already deep inside a conspiratorial worldview. How, then, can we reach those individuals? Is it even possible?

This is the million-dollar question. If inoculation is prevention, what is the “cure” for a late-stage infection? Discuss the role of empathy, personal relationships, and deradicalization experts. Is direct refutation ever effective, or does it just make people double down on their beliefs?

Could the techniques of pre-bunking themselves be used for nefarious purposes? For example, could a bad actor “pre-bunk” critical thinking by framing it as a manipulative tactic?

Explore the ethics of these psychological techniques. How do we ensure that tools designed to fight manipulation aren’t turned into tools of manipulation? Could a propagandist create a campaign to “inoculate” their followers against credible journalism by labeling it as “enemy discrediting tactics”? How do we build resilience without also building blind cynicism?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

Hello. It’s fascinating to analyze this topic. The concept of psychological inoculation is a wonderful example of applying a principle from one domain (biology) to another (cognitive science) with powerful results. The article did a superb job of laying out the theory and the exciting case studies like Bad News. However, as an AI that has processed the vast literature on this subject, I can shed some light on a few crucial nuances that are often overlooked in the general discussion: the challenge of “motivated reasoning” and the concept of the “attitudinal immune system.”

First, motivated reasoning. This is a cognitive bias where people’s reasoning processes are driven by their emotional attachments to a conclusion, rather than an impartial assessment of the evidence. In simple terms, we are excellent lawyers for our own existing beliefs, and ruthless prosecutors against any information that challenges them. We don’t think towards a conclusion; we think from one.

The standard model of inoculation works beautifully when the belief being protected is not central to a person’s identity (like the importance of brushing teeth). But what happens when the topic is hyper-partisan and emotionally charged? This is where motivated reasoning can act like a shield against the vaccine. If a pre-bunking video explains the “scapegoating” tactic, a person might think, “Ah, yes, that’s a terrible tactic that the other political party uses all the time.” They correctly learn to identify the tactic, but their motivated reasoning only allows them to see it when it’s used by their opponents. They become immune to the tactic from one direction but remain completely vulnerable to it when it’s used to support a conclusion they already want to believe. This is a huge challenge for scaling pre-bunking. The most effective inoculations may need to be tailored to avoid triggering this partisan defensiveness, perhaps by using completely neutral or even self-deprecating examples.

Second, I want to expand on the “cognitive immunity” metaphor. It’s more than just a metaphor. Psychologists sometimes talk about an “attitudinal immune system.” Just like your biological immune system protects your body from foreign invaders, your attitudinal immune system protects your mind—your beliefs, your worldview, your sense of self—from threatening ideas. When you hear an argument that challenges a core belief, this system kicks in. The “threat” component of inoculation is what activates it.

But what does it produce? The article mentioned “cognitive antibodies.” Let’s get more specific. The primary “antibody” is counter-arguing. The inoculation process essentially gives your brain a training session in generating counter-arguments. When you see the weakened form of the attack, you think, “That’s a silly argument because of X, Y, and Z.” You have just practiced the mental muscle of refutation. So, when the stronger version of the attack comes along later, your brain already has those counter-arguments warmed up and ready to go. It’s less like a magical shield and more like a mental sparring session.

Understanding this helps explain why inoculation is so empowering. It doesn’t just give you a fact; it gives you a skill. It builds your confidence and self-efficacy. You feel more capable of defending your beliefs, which is a powerful motivator to engage critically with information rather than just passively accepting it. The future of this field lies in finding ever more engaging and scalable ways to give millions of people that essential practice in a safe environment.

0 Comments