- The Anatomy of a Crisis

- The Golden Hour: Speed vs. Accuracy

- The Tale of Two Crises: Tylenol vs. BP

- Decision Making in the Fog

- The Human Element: Empathy as a Strategy

- Post-Crisis: The Autopsy

- The Captain in the Storm

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis: Devil’s Advocate

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Boss

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

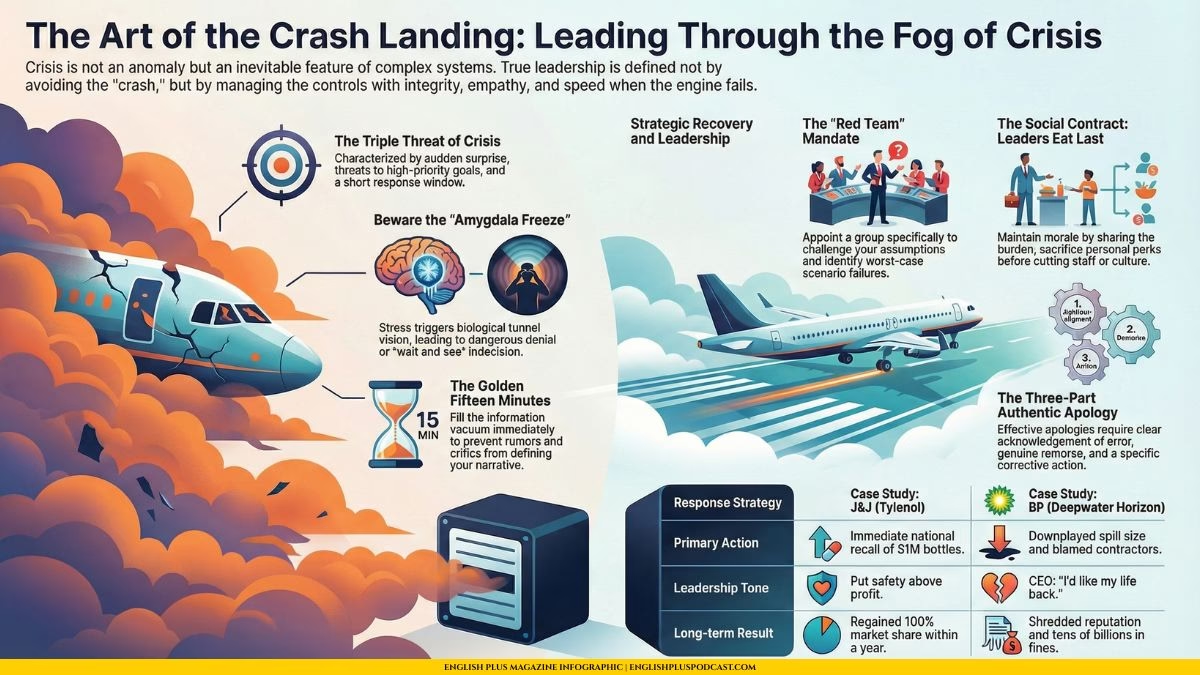

There is a pervasive myth in the business world—and frankly, in life generally—that if you are smart enough, careful enough, and work hard enough, you can avoid disaster. We build our five-year plans, we construct our SWOT analyses, and we surround ourselves with data that whispers sweet nothings about “steady growth” and “market stability.” We convince ourselves that the storm happens to other people, usually the ones who didn’t read the right management books.

But here is the uncomfortable truth: The storm is coming for everyone. It doesn’t matter if you are the CEO of a Fortune 500 conglomerate, the owner of a local bakery, or just someone trying to manage a particularly chaotic household. At some point, the engine will fail. The server will crash. The supply chain will snap. A PR nightmare will explode on Twitter while you are sleeping.

Crisis is not an anomaly; it is a feature of the system.

The true measure of leadership isn’t preventing the crisis—though that helps—it’s how you handle the controls when the plane starts losing altitude. Crisis management is the dark art of making terrible decisions under immense pressure with incomplete information, all while everyone is watching you to see if you blink. It is about navigating the fog of war without losing your soul or your shareholders.

The Anatomy of a Crisis

Before we talk about what to do, we have to agree on what a crisis actually is. A bad quarter isn’t a crisis; that’s a problem. A competitor launching a better product isn’t a crisis; that’s a challenge.

A crisis is an event that threatens the very existence or reputation of your organization. It is characterized by three things: surprise, a threat to high-priority goals, and a short amount of time to respond. It is the moment when the status quo is violently ejected from the building.

The Psychology of the Freeze

When a crisis hits, biology takes over. Our ancient reptilian brain, which is excellent at spotting saber-toothed tigers but terrible at handling data breaches, kicks into gear. We experience a flood of cortisol. Our vision tunnels. Our cognitive flexibility vanishes.

This is why you see otherwise brilliant executives freeze up or make bafflingly stupid decisions in the first 24 hours of a disaster. They are not thinking with their prefrontal cortex; they are thinking with their amygdala. They retreat into denial. You hear phrases like, “Let’s wait and see,” or “Maybe it will blow over.”

Spoiler alert: It never blows over. In the digital age, bad news travels faster than light, and silence is interpreted as guilt. The first step in effective crisis leadership is managing your own biology. You have to recognize the panic, acknowledge it, and then deliberately step past it. You cannot command a ship if you are hyperventilating in the captain’s quarters.

The Golden Hour: Speed vs. Accuracy

In emergency medicine, there is a concept called the “Golden Hour”—the window of time following a traumatic injury when prompt medical treatment has the highest likelihood of preventing death. In business, that window is now more like the “Golden Fifteen Minutes.”

When something goes wrong, a vacuum of information is created instantly. If you do not fill that vacuum with your narrative, someone else will. And that “someone else” will usually be angry customers, cynical journalists, or conspiracy theorists on social media.

The Paradox of Information

Here is the cruel paradox of crisis management: You need to speak immediately, but you don’t know anything yet.

If a factory explodes, the press wants to know why five minutes later. But you won’t know the technical why for weeks. Leaders often get paralyzed here. They feel they shouldn’t speak until they have the facts. But waiting for “all the facts” is a death sentence.

The solution is to communicate what you do know, admit what you don’t know, and explain what you are doing to find out. There is immense power in saying, “We are aware of the incident. We do not yet know the cause, but our priority right now is the safety of our employees. We have emergency crews on-site and will update you in one hour.”

That statement contains almost no hard data, yet it establishes competence, empathy, and a timeline. It tells the world, “I am here. I am awake. I am working on it.” It buys you the most valuable commodity in a crisis: trust.

The Tale of Two Crises: Tylenol vs. BP

To understand the stakes, we have to look at the history books. There are two case studies that are taught in every business school for a reason. They represent the gold standard of success and the masterclass in failure.

The Johnson & Johnson Masterstroke

In 1982, seven people in Chicago died after taking Extra-Strength Tylenol that had been laced with cyanide. It was a terrifying, random act of terrorism. Johnson & Johnson, the parent company, faced a nightmare. Tylenol was their cash cow.

Their response was aggressive and counter-intuitive. They didn’t try to hide. They didn’t try to spin it as a “Chicago problem.” They immediately recalled 31 million bottles of Tylenol from store shelves nationwide, costing them over $100 million. They halted all advertising. They cooperated fully with the police and the media.

Then, they reinvented packaging. They introduced the tamper-evident seal that we all struggle to open today. They put safety above profit in a way that was so visible, so undeniable, that Tylenol actually regained its market share within a year. They didn’t just survive the crisis; they used it to define their corporate character.

The BP Oil Spill Debacle

Contrast this with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. An oil rig exploded, killing eleven workers and spewing millions of barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. It was an ecological catastrophe.

BP’s then-CEO, Tony Hayward, committed every sin in the book. He downplayed the spill’s size. He blamed contractors. He was photographed yachting while the Gulf coast was covered in sludge. And then, he uttered the sentence that killed his career: “I’d like my life back.”

It was a moment of breathtaking narcissism. In the middle of a tragedy affecting millions of lives and an entire ecosystem, the leader made it about his personal inconvenience. BP survived, but its reputation was shredded, and it cost them tens of billions of dollars in fines and clean-up costs.

The lesson? In a crisis, you are the least important person in the room. If you focus on protecting your ego or your bonus, you will lose everything. If you focus on the victims, you might just save the company.

Decision Making in the Fog

Once the initial statement is out, the grinding work begins. Crisis management is essentially a series of high-stakes bets made with bad cards. You have to make decisions that will have long-term consequences, but you are operating in a fog of rumors, legal threats, and operational failures.

The Red Team Approach

One of the most effective strategies is to establish a “Red Team.” When you are in the bunker, you tend to develop groupthink. Everyone wants to agree with the boss; everyone wants the optimistic scenario to be true.

You need to appoint a group of smart people whose specific job is to challenge your assumptions. Their job is to tell you why your plan will fail. They should ask the brutal questions: “What if the leak is worse than we think?” “What if the press finds out we cut the maintenance budget?” “What if the fix doesn’t work?”

This feels uncomfortable. No one likes a naysayer when the house is on fire. But you need the naysayer to point out that you are trying to put out the fire with gasoline. Listening to the worst-case scenario allows you to prepare for it.

Avoiding the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Crises often escalate because leaders refuse to cut their losses. They double down on a bad strategy because they have already invested time and money into it. This is the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

Effective crisis leaders are ruthless about pivoting. If the initial statement was wrong, correct it immediately. If the product fix isn’t working, recall the whole line. There is no shame in saying, “We thought X, but new data shows Y, so we are doing Z.” The public will forgive a leader who evolves; they will crucify a leader who stubbornly clings to a lie.

The Human Element: Empathy as a Strategy

We often talk about crisis management in terms of logistics, legalities, and PR. But at its core, it is an emotional event. People are scared. Employees are worried about their jobs. Customers are worried about their safety.

Empathy is not just a “soft skill” here; it is a hard strategic asset.

Internal Communication First

Many leaders make the mistake of focusing entirely on the external media, forgetting the thousands of people who actually work for them. Your employees are your ambassadors. If they find out about the crisis on the news, you have lost them.

You need to talk to your team. You need to be vulnerable. It is okay to say, “This is a difficult time, and I know you are worried. Here is what we are doing.” When employees feel included and informed, they rally. They work the extra hours to fix the bug. They defend the brand at the dinner table. If they feel treated like pawns, they leak damaging emails to the press.

The Apology

Let’s talk about the apology. It is an art form that most corporations are terrible at. The standard corporate apology reads like it was written by a lawyer trying to avoid a lawsuit—because it usually was. “We regret if anyone took offense” is not an apology. “Mistakes were made” is not an apology.

A real apology has three parts:

- Acknowledgement: “We messed up.”

- Remorse: “We are truly sorry for the pain this caused.”

- Action: “Here is how we are going to fix it and ensure it never happens again.”

Authenticity cuts through the noise. When KFC ran out of chicken in the UK (a crisis that is objectively funny but operationally disastrous), they ran a full-page ad rearranging the letters KFC to say “FCK.” It was risky, it was human, and it worked. It acknowledged the absurdity of the situation and apologized without sounding like a robot.

Post-Crisis: The Autopsy

Eventually, the bleeding stops. The cameras go away. The stock price stabilizes. This is the most dangerous moment because the temptation is to pop the champagne and go back to “business as usual.”

Do not do that.

You have just paid a very expensive tuition fee for a lesson in your own vulnerabilities. You need to conduct a ruthless autopsy. This isn’t a witch hunt to find someone to fire (though sometimes people need to be fired). It is a systems analysis.

Why did the valve fail? Why did the manager ignore the warning signs? Why did our backup servers crash?

Resilience, Not Just Recovery

The goal shouldn’t be to bounce back to where you were before. The goal should be to bounce forward. This is the concept of “Antifragility”—building a system that gets stronger when it is stressed.

The airline industry is the safest mode of transport in history because of its obsession with autopsies. Every time a plane crashes, the entire industry learns why, and they change the hardware, the software, or the pilot training to ensure that specific crash never happens again. Business leaders need that same mindset. If you waste a crisis, you are just waiting for the sequel.

The Captain in the Storm

Leading through a crisis is lonely. It is exhausting. It reveals who you really are. When the waters are calm, anyone can hold the helm. It is only when the waves are crashing over the bow that we see the difference between a title-holder and a leader.

You will make mistakes. You will lose sleep. You might even lose your job. But if you can navigate the storm with integrity, if you can communicate with clarity, and if you can treat people with humanity even when the world is burning down, you will have done the job.

The engine will fail. That is inevitable. But the crash landing? That is up to you.

Focus on Language

Let’s take a moment to really dissect the language we’ve been using here. Business English, especially regarding crisis management, is filled with specific terminology that carries a lot of weight. It’s not enough to just know the dictionary definition; you need to understand the “flavor” of these words—the nuance they carry in a boardroom or a press conference. I want to highlight ten specific terms and phrases from our discussion and show you how to wield them like a pro.

First up is “Mitigate.” You hear this everywhere in risk management. To mitigate means to make something less severe, serious, or painful. We don’t usually say “fix” a risk, because risks can rarely be completely fixed. We say “mitigate the risk.” In real life, if you are late for a meeting, you might text ahead to say, “I’m bringing donuts to mitigate the annoyance of my lateness.” It implies you are taking active steps to soften the blow.

Next, let’s talk about “The Fog of War.” This is a military term coined by Carl von Clausewitz, but we use it constantly in business. It refers to the uncertainty in situational awareness experienced by participants in military operations. In a business crisis, it describes that chaotic period where you have too much data, but no information. You might say, “We made the wrong call on the pricing, but we were operating in the fog of war.” It’s a sophisticated way of saying, “It was chaotic and we were confused,” but it sounds much more strategic.

Then we have “Contingency.” A contingency is a future event or circumstance that is possible but cannot be predicted with certainty. A “contingency plan” is your Plan B. If you want to impress your boss, don’t ask “What if this goes wrong?” Ask, “Do we have a contingency for a supply chain disruption?” It shows you are thinking ahead about structural failures.

Let’s look at “Stakeholder.” This is broader than “shareholder.” A shareholder owns stock. A stakeholder is anyone who is affected by your actions—employees, customers, the local community, the government. In a crisis, you have to manage multiple stakeholders. Use this when you want to show you are seeing the big picture. “We need to consider how this policy affects all our stakeholders, not just the investors.”

A powerful phrase we used is “Control the Narrative.” This doesn’t mean lying. It means being the primary source of information so that you define the story, rather than letting rumors define it. If you break up with someone and tell your friends your side of the story first, you are controlling the narrative. If you wait until your ex posts on Instagram, you have lost the narrative.

We discussed the “Sunk Cost Fallacy.” This is an economic term describing the phenomenon where a person is reluctant to abandon a strategy because they have heavily invested in it, even when it is clear that abandonment would be more beneficial. In daily life, this is finishing a terrible book just because you read the first 100 pages. Recognizing the sunk cost fallacy allows you to quit things that aren’t working without feeling guilty.

Let’s touch on “Liability.” In law, this means being responsible for something. In business, it often refers to a vulnerability or a risk. “That old server is a liability.” But we also use it to describe people. “He’s a great salesman, but his temper is a liability.” It means they are a risk to the organization.

Another great one is “Optics.” This refers to the way a situation looks to the general public. Sometimes a decision makes financial sense but has terrible optics. For example, giving the CEO a bonus while laying off workers has terrible optics. You might say, “I know it’s legal, but the optics are going to be a nightmare.”

We used the term “Post-Mortem.” Literally, “after death.” In business, it’s the meeting held after a project or crisis is over to analyze what went wrong and what went right. “Let’s schedule a post-mortem on the product launch.” It implies a blameless, analytical look at the process.

Finally, “Resilience.” This isn’t just toughness. Resilience is the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties. In materials science, a resilient material bends and snaps back. In psychology and business, it’s the ability to absorb a shock and keep functioning. “The team showed incredible resilience during the merger.”

Speaking Section: The Executive Briefing

Now, let’s put these words into your mouth. The goal here is to sound authoritative but calm. When speaking about a crisis, your tone matters as much as your vocabulary. You want to use “downward inflection”—dropping the pitch of your voice at the end of sentences. This signals certainty. Upward inflection signals doubt.

The Challenge:

I want you to imagine you are a project manager. Your project is two weeks behind schedule because a key software tool crashed. You have to explain this to your boss.

Don’t say: “Um, sorry, the software broke and we are late.”

Try using our vocabulary. I want you to say this out loud:

“We are currently navigating a contingency situation regarding the software crash. The optics of the delay aren’t great, but we are taking steps to mitigate the impact on the final deadline. We will conduct a full post-mortem once the system is back online to ensure resilience moving forward.”

Do you feel the difference? One sounds like a victim; the other sounds like a leader. Your assignment is to take a small problem in your life—a burnt dinner, a missed bus, a lost file—and describe it to yourself in the mirror using three of the keywords above. Elevate the mundane into the strategic.

Critical Analysis: Devil’s Advocate

We have spent a lot of time praising the “Tylenol Model” and the virtues of transparency, empathy, and rapid response. It’s a great narrative. It feels morally right. But if we are being rigorous thinkers, we have to admit that the real world is messier than a textbook case study. Let’s play devil’s advocate and poke some holes in the standard crisis management wisdom.

First, let’s challenge the “Total Transparency” doctrine. The conventional wisdom is “tell it all, tell it fast, tell it yourself.” But is that always smart? Legal counsel will often scream “NO” for a reason. Admitting fault in the “Golden Hour” can open you up to massive liability before you even know if you are actually at fault. There are times when Strategic Silence is the superior play. If the crisis is a bubbling Twitter controversy that is based on a misunderstanding, issuing a massive formal apology might just fan the flames and bring attention to something that would have died a natural death in 24 hours. The “Streisand Effect”—where trying to suppress or address info makes it more popular—is real. Sometimes, the best crisis management is to shut up and let the news cycle move on to the next victim.

Second, let’s look at the “Hero Leader” myth. We love the idea of the stoic CEO steering the ship. But this obsession with the individual leader can be dangerous. It creates a single point of failure. If the CEO is the “face” of the recovery, and then the CEO turns out to be part of the problem (or just makes a human gaffe), the recovery collapses. Furthermore, the “Hero Leader” narrative often ignores the reality of Distributed Leadership. In a complex crisis—like a cyberattack—the CEO is useless. The real decisions are being made by the IT security lead and the legal team. Pretending the CEO is in charge can actually slow down the experts. Maybe we should stop looking for a savior in the C-suite and start trusting the systems.

Third, we have to talk about the “Learning from Mistakes” fallacy. We love to say “we will learn from this.” But organizational memory is incredibly short. When the crisis fades, the budget for “resilience” is usually the first thing to be cut because it doesn’t generate revenue. Companies are profit-maximizing machines, not learning machines. Unless there is a regulatory penalty that makes the risk more expensive than the prevention, companies will rarely fundamentally change their behavior. They will fire the scapegoat, rebrand, and go back to the risky behavior that caused the crisis because it is profitable. Is “resilience” real, or is it just a buzzword we use to make ourselves feel safer?

Finally, consider the cost of Over-Preparation. We talked about Red Teams and contingencies. But you can suffer from “Paralysis by Analysis.” You can build so many safety protocols and check-ins that the organization becomes sclerotic. It can’t move. In trying to prevent a crisis, you create a bureaucracy that kills innovation. A company that takes zero risks will never have a crisis, but it will also never have a breakthrough. Maybe a certain level of crisis is just the tax we pay for speed and innovation.

These counter-points don’t mean the main article is wrong. They just mean that context is king. Transparency is usually good, but not always. Apologies are powerful, but sometimes dangerous. And learning is essential, but rarely happens automatically. The art is knowing when to follow the rulebook and when to burn it.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to spark deep conversation about crisis management. These aren’t just for business; they apply to politics, relationships, and ethics.

Is it ever ethical to lie in a crisis to prevent panic?

Think about a government knowing a bank run is coming. If they tell the truth (“The banks are shaky”), they cause the panic they fear. If they lie (“The banks are safe”), they might prevent it, or they might trap people in a doomed system. Where is the line between “calming the public” and “deceiving the public”?

Does social media make true forgiveness impossible for public figures?

In the past, a crisis would fade. Today, the internet is an eternal archive. If a leader makes a mistake, the video of that mistake exists forever. Does this permanent record force leaders to be more defensive and less authentic because they know a single slip-up is a life sentence?

Can a crisis actually be good for a company in the long run?

We discussed Tylenol. But think about New Coke. It was a disaster, but the return of “Coca-Cola Classic” revitalized the brand. Can you manufacture a crisis to create a comeback narrative? Or is that too conspiracy-theory?

Who deserves more empathy in a corporate crisis: the employees or the customers?

Often their interests are opposed. To save the company (and customer service), you might need to lay off employees. To protect employees, you might need to raise prices or cut services. Who is the primary “stakeholder”?

At what point does a “reason” become an “excuse”?

When a leader explains why something went wrong (e.g., “The supply chain was disrupted by weather”), it explains the context. But audiences often hear it as dodging responsibility. How do you explain the context without looking like you are passing the buck?

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Boss

Danny: Welcome back to the show. We’ve been talking about crisis management—how to lead when the servers crash, when the PR nightmare hits, when the stock plummets. But let’s be honest, in the corporate world, “disaster” usually means losing a bonus or getting fired. It rarely means freezing to death on an ice floe. To understand what real crisis leadership looks like, I wanted to talk to the man who wrote the playbook on survival. He is the leader of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. He lost his ship, he lost his mission, but—and this is the important part—he didn’t lose a single man. Please welcome “The Boss,” Sir Ernest Shackleton. Sir Ernest, welcome to the studio. I hope the temperature is to your liking.

Shackleton: It is positively tropical, Danny. I was half tempted to take off my coat, but I see you are wearing a rather thin shirt. I wouldn’t want to make you feel underdressed.

Danny: I appreciate that. Now, Sir Ernest, business schools today treat your expedition as the ultimate case study in leadership. But let’s set the scene. It’s 1915. Your ship, the Endurance, is trapped in pack ice. It’s being crushed. You are thousands of miles from civilization with no radio. That is a “crisis.” Today, a CEO calls it a crisis if the Wi-Fi goes down for an hour. Do you find our modern definition of “disaster” a bit… cute?

Shackleton: “Cute” is a polite word for it. I find it fascinatingly fragile. You see, Danny, in my day, a crisis was physical. The ice rips the hull. The food runs out. The temperature drops to sixty below. The threat is tangible. Today, your crises seem to be entirely imaginary. “Reputation.” “Brand sentiment.” “Twitter backlash.” You are terrified of ghosts. You are terrified of words floating in the ether. It is much harder to lead men against ghosts than it is against ice. Ice, you can hack with a pickaxe. How do you hack a “tweet”?

Danny: You block the user, usually. But let’s talk about the moment the Endurance went down. In the article, we discussed the “Sunk Cost Fallacy”—the refusal to abandon a plan because you’ve already invested in it. You literally watched your investment sink. What went through your mind? Did you try to save the mission?

Shackleton: Save the mission? Good God, no. The moment the timber cracked—that terrible sound, like a gun going off—I knew the mission was dead. A man must shape himself to a new mark directly the old one goes to ground. That is the first rule of command. Most leaders, I observe, fall in love with their plans. They treat the plan like a child. They want to nurture it even when it is clearly dead. When the Endurance sank, I gathered the men. I didn’t say, “Perhaps we can still reach the Pole.” I didn’t say, “Let’s wait and see.” I said, “Ship and stores have gone. So now we’ll go home.”

Danny: That’s the “Pivot” we talk about. But it must have been heartbreaking. You spent years raising money for that ship.

Shackleton: Heartbreak is a luxury for the warm. When you are standing on a floating sheet of ice that is slowly melting, you do not have time for nostalgia. This is where your modern CEOs fail. They spend weeks mourning the loss of a market share. They hold meetings to discuss why the market changed. Who cares why? The ship is gone! Grab the dogs, grab the pemmican, and start walking. Speed, Danny. The speed of acceptance is the speed of survival.

Danny: Let’s talk about morale. You were famous for keeping your crew optimistic. In a corporate crisis, we talk about “controlling the narrative.” How did you control the narrative when the narrative was “we are almost certainly going to die”?

Shackleton: You don’t lie to men. They can see the ice. They can feel the cold. If I had told them, “Don’t worry, lads, a rescue ship is just around the corner,” they would have mutinied. False hope is poison. It is far worse than despair. But you can control the focus. I instituted a routine. Strict meal times. Games of football on the ice. Haircuts. We celebrated birthdays. We had a rigid schedule of socialization.

Danny: Haircuts? You’re stranded in Antarctica and you’re worrying about styling?

Shackleton: It wasn’t about the style, Danny. It was about civilization. When the external world turns into chaos, you must create an internal world of order. If you let men become beasts—if you let them stop washing, stop shaving, stop saying “please” and “thank you”—then the despair sets in. The “crisis” enters their soul. Once the crisis is inside the man, he is finished. A CEO facing a scandal must do the same. Keep the routine. Keep the meetings. Keep the standards. Do not let the chaos of the market destroy the culture of the office.

Danny: That connects to what we call the “Red Team” approach. You had some difficult personalities on your crew. There was the carpenter, Chippy McNeish. He rebelled. In the corporate world, we usually fire the naysayers during a crisis. You didn’t.

Shackleton: Fire him? To where? An iceberg three miles south? No, I did something different. I kept the troublemakers close. I had the “Potentate’s Tent”—my tent. And I invited the most difficult, pessimistic men to sleep in my tent.

Danny: Wait, you slept with the people who hated you?

Shackleton: I slept with the people who were afraid. Pessimism is usually just fear dressed up as intelligence. McNeish wasn’t a bad man; he was terrified. If I left him in the other tents, his fear would spread like a virus. It is mental bacteria. By keeping him close, I could treat the infection. I could listen to him. I could reassure him. I could keep an eye on him. A leader who isolates himself with his “Yes Men” during a crisis is a fool. You must keep your enemies—or your doubters—close enough to share your body heat.

Danny: That is a brilliant, if uncomfortable, strategy. “Keep your friends close and your pessimists in your sleeping bag.”

Shackleton: It wasn’t the most fragrant experience, I admit. But it worked.

Danny: Let’s discuss the “Golden Hour.” The moment when disaster strikes and you have to act. We argue that leaders often freeze. Did you ever freeze?

Shackleton: Freeze mentally? No. But I paused. There is a difference. When the ship was crushed, everyone looked at me. They were waiting for the scream, the panic. Instead, I made them a cup of tea.

Danny: Tea?

Shackleton: Tea. It is the British solution to everything, is it not? But it served a purpose. It broke the paralysis. It signaled that we still had resources, we still had comfort, and we had time to think. A leader who runs around screaming orders immediately often gives the wrong orders. You need a moment of quiet calculation. The “Golden Hour” isn’t about moving fast; it’s about thinking clearly while moving fast.

Danny: In the article, we contrasted the “Tylenol” response—total responsibility—with the “BP” response—deflection. You were the ultimate responsible party. But you also made mistakes. You picked the wrong ship. You got trapped. Did you apologize to your men?

Shackleton: I didn’t apologize in words. I apologized in service. This is something your modern “Bosses” have forgotten. They think leadership is a privilege. They take the biggest bonus, the corner office. On the ice, leadership is a burden. When we ran out of sleeping bags, and we had to switch to the cold, wet ones, I took the worst bag. When we were short on food, I took the smallest biscuit.

Danny: You starved yourself for them?

Shackleton: It wasn’t martyrdom, Danny. It was strategy. If the men see the Boss eating a steak while they eat scraps, the bond breaks. And when the bond breaks on the ice, you eat each other. In your corporate world, I see CEOs laying off thousands of workers while keeping their private jets. That is cannibalism. It is a failure of the “Social Contract.” If you want men to follow you into hell, you must be the first one to step into the fire.

Danny: That’s powerful. “Leadership is a burden.” Most people today think leadership is a career path to a summer home in the Hamptons.

Shackleton: A summer home? I came home to debt. I spent the rest of my life paying off the expedition. But I walked down the gangplank with 27 men who were supposed to be dead. That is a profit margin you cannot put on a spreadsheet.

Danny: Let’s talk about “Optics.” You were very aware of how things looked. You famously threw away your gold watch on the ice, but you kept a banjo. Why?

Shackleton: The gold watch was heavy metal. It was wealth. It had no value in survival. I threw it away to show the men that “wealth” was now meaningless. We were resetting the currency. But the banjo… that was Hussey’s banjo. It was heavy, yes. It was awkward. But it was music. It was medicine. To throw away the gold but keep the music sent a message: We are discarding the past, but we are keeping our humanity.

Danny: That’s a masterclass in symbolism. Today, a company might fire the janitors to save money (throwing away the banjo) but keep the expensive consultants (keeping the gold watch).

Shackleton: Precisely. They cut the culture to save the cash. It is suicidal. The culture is what gets you home. The cash is just ballast.

Danny: I want to ask about the “Fog of War.” You made an 800-mile journey in a small lifeboat, the James Caird, across the worst ocean in the world to get help. You couldn’t see the sun for navigation. You were guessing. How do you make decisions when you literally cannot see where you are going?

Shackleton: You rely on dead reckoning. You take your best guess based on where you were yesterday. And you trust your gut. But mostly, Danny, you just keep the boat afloat for one more hour. That is the secret. You don’t try to solve the whole ocean. You solve the next wave. Then the next. Then the next. Your modern strategists want a “5-Year Plan.” In a crisis, a 5-Year Plan is a hallucination. I had a “5-Minute Plan.” Keep the water out. Steer north. Don’t die.

Danny: “Solve the next wave.” That’s actually incredibly relieving. We get so paralyzed by the big picture.

Shackleton: The big picture will crush you. The small picture is manageable. Can you survive the next meeting? Good. Can you survive the next press release? Good. Eventually, you hit land.

Danny: Let’s talk about “Resilience” and “Antifragility.” You survived. You came home. And then… you went back! You launched another expedition. Why? Most people would have retired to a quiet cottage.

Shackleton: Because I am a man of the ice. But also because a crisis changes you. It strips away the varnish. You realize that “normal” life is incredibly boring. I see this in your business leaders too. The ones who survive a bankruptcy or a hostile takeover… they are different. They are harder. They are calmer. They know the worst that can happen, and they know they can endure it. The “Antifragile” man needs the storm. The calm water makes him soft.

Danny: So, we shouldn’t fear the crisis?

Shackleton: You should respect the crisis. But fear it? No. A life without a crisis is a life without a test. How do you know who you are if you have never been crushed? I know who I am, Danny. I am the man who brought them home. Who are you?

Danny: I… I am the man who podcasts?

Shackleton: We all have our cross to bear.

Danny: One last question. If you were the CEO of a modern tech company—let’s say, Twitter or Facebook—and everything was crashing down. What is your first memo to the staff?

Shackleton: I would write: “Men and Women wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.”

Danny: That’s your famous recruitment ad! You think that works for coders?

Shackleton: It works for believers. If you promise them a beanbag chair and free sushi, you get mercenaries. If you promise them a struggle and glory, you get warriors. In a crisis, you don’t need employees. You need a crew.

Danny: Sir Ernest Shackleton, you make me want to go freeze to death just to feel something. Thank you for joining us.

Shackleton: You are welcome. Now, do you have any biscuits? I skipped lunch.

Danny: I think we have some stale bagels in the breakroom.

Shackleton: Stale bagels? Luxury! Lead the way.

Danny: Folks, there you have it. The man who pivoted from “Explorer” to “Survivor” without blinking. He teaches us that culture beats strategy, that leaders eat last, and that sometimes, the most important thing you can do in a crisis is throw away your gold watch and keep the banjo.

0 Comments