Before You Read

Welcome, fellow reader! Before we step onto the damp, mossy stones of Oakhaven, let’s take a moment to set our compass. “The Keeper of the Spring” is what we might call a modern fable or a parable. You don’t need any special historical knowledge or a dictionary of obscure terms to understand it; the story speaks a universal language. It taps into anxieties and questions that humanity has wrestled with since the dawn of civilization—and questions that are arguably more relevant today than ever before.

As you prepare to read, I want you to think about the spaces in your own life that belong to everyone. Think about public parks, the air we breathe, the oceans, or even the quiet moments of the morning before the rush of the day begins. These are the “commons.” For centuries, communities have had to figure out how to share these shared resources without destroying them. It requires patience, a sense of collective responsibility, and an understanding that we are all part of a delicate web.

This story is going to ask you to weigh two very different ways of living. On one side, you have the slow, steady rhythm of tradition. It might not be glamorous, and it certainly requires a bit of waiting in the mud, but it works. It keeps everyone alive, and more importantly, it keeps everyone together. On the other side, you have the intoxicating promise of “progress.” It’s shiny, it’s efficient, and it promises to make life easier and more profitable. But progress often comes with a hidden price tag, usually paid by those who can least afford it.

You are about to meet a village at a crossroads. Keep an eye on how the characters define “wealth.” Is wealth having enough water for the day, or is it having a mountain of gold coins? Watch how the language of business and bureaucracy begins to creep into a place that used to run on simple, silent understanding. Notice how quickly a community can fracture when the rules change from “take what you need” to “take what you can afford.”

You don’t need to overthink it as you read. Let the atmosphere wash over you. Feel the cold chill of the mountain spring, hear the quiet chatter of the morning queue, and notice how the air changes when the smell of lye and ambition enters the valley. This is a story about water, yes, but it’s really a story about the human heart, the seduction of comfort, and the tragic realization of what truly matters when the well runs dry. Open your mind, take a deep breath, and let’s head to Oakhaven.

The Keeper of the Spring

Part I: The Rhythm of the Mountain

In the village of Oakhaven, water was not merely a resource; it was the village’s heartbeat, a cold, liquid silver that dictated the tempo of every life. Every drop used to boil an egg, wash a child’s face, or dampen the clay of the potter’s wheel came from a single source: the Mountain Spring. It was a crystalline vein that pulsed from the granite heart of the peak above, spilling into a stone basin that had been worn smooth by a thousand years of dipping buckets and the quiet prayers of the thirsty.

For forty years, the basin had been guarded by the Elder Keeper. He was a man who looked like he had been carved from the same mountain—craggy, silent, and immovable. His skin was the color of weathered shale, and his eyes had the clarity of a high-altitude lake. He lived in a shack that leaned against the rock, a structure of driftwood and moss that seemed more like a natural outcropping than a human dwelling. His life was one of monastic simplicity; he owned two shirts of coarse linen, a bed of straw, and a single wooden ladle.

The Law of the Spring was inscribed on a weathered plaque of dark oak above the basin, its letters softened by decades of mist: “Take what you need for the day, and no more.”

Life in Oakhaven was defined by the Line. Because the spring flowed at a constant, unhurried pace—neither rushing for the desperate nor slowing for the idle—a queue formed every morning at dawn. It was a slow, egalitarian crawl. The rich merchant stood behind the stable hand; the village healer waited her turn behind the schoolteacher. There were no shortcuts, no exceptions, and no bribes. The Line was the great leveler of Oakhaven society. In that morning silence, while the mist still clung to the valley floor, the villagers talked. They shared news of births and deaths, negotiated the price of grain, and settled disputes before they could fester. The Line was where the community forged itself.

The Elder Keeper stood at the head of the Line, a silent sentinel. He didn’t need to shout or lecture. If a man brought two buckets when his family only needed one, the Keeper’s heavy, disappointed gaze was enough to make the man’s ears burn with shame. He would pour the excess back into the basin, the water splashing with a sound that seemed to echo the Keeper’s silent judgment.

The water was free. The cost was time—a currency that everyone possessed in equal measure.

When the Elder Keeper finally passed away—found seated in his wooden chair, facing the sunrise with a peaceful, sightless stare—the village mourned with a heavy heart. But beneath the grief was a quiet, restless energy. The elders remembered the old ways, but the younger generation looked at the hours spent waiting in the mud and felt a growing impatience. Surely, in this modern age of mechanics and trade, there was a better way to manage a mountain’s gift.

Part II: The Architect of Progress

The Village Council, seeking a fresh vision, appointed Hector to the position of Keeper. Hector was thirty, with eyes that were always calculating and hands that never seemed to rest. He had studied in the sprawling cities across the plains, where water moved through lead pipes and time was measured in gold. He spoke with a cadence of efficiency that the elders found intoxicating and the ambitious found inspiring.

“The Mountain provides plenty,” Hector told the Council during his inaugural address, gesturing toward the peak with a rolled blueprint. “The problem isn’t the water. The problem is the delivery. Why should a master weaver or a skilled blacksmith lose two hours of productive labor every morning just to fill a jug? We are a village of the past, standing ankle-deep in the mud of our own traditions. I will bring us into the future. I will make the Spring serve Oakhaven, rather than Oakhaven serving the Spring.”

For the first few months, Hector was a secular saint. He began by cleaning the basin, scrubbing away the emerald moss that the Elder Keeper had left untouched for decades. He claimed the moss was a “contaminant,” though the water had never been purer. He noticed the path leading to the spring was a quagmire during the rainy season, a source of constant complaint. Using his own meager stipend, he hired a few laborers to lay down flat, grey stones, creating a dry walkway.

But stones cost money, and the stipend was designed for the Elder Keeper’s straw-bed lifestyle, not for civil engineering.

It was during his third month that Varg, the master dyer, approached him. Varg was a man of secondary colors—his fingernails were permanently stained indigo, his forearms were a mottled crimson, and his breath smelled of lye and ambition. He ran the largest workshop in Oakhaven, producing the vibrant linens that were the village’s primary export to the capital.

“Hector,” Varg said, leaning against the new stone path and tapping it with a polished cane. “This path is a marvel of foresight. But my business is suffering under the old ‘Law.’ I have an order for three hundred bolts of crimson silk for the Royal Court. If my men wait in the Line every morning, I cannot fulfill the contract. The village loses the trade tax. I lose my profit. And the Spring… well, it just sits there at night, spilling its wealth into the dirt while the village sleeps. It’s an architectural tragedy.”

Hector frowned, his mind already racing through the logic. “The Law says the water is for the day, Varg. It belongs to the people.”

“The Law was written by a man who didn’t understand the velocity of money,” Varg whispered, his voice smooth as silk. “Let me come at three in the morning. I’ll bring my own team. We won’t take a single drop from the morning Line. In exchange, I will pay a ‘Maintenance Fee’ directly to the Keeper’s office. You can use it to pave the rest of the road. You could even build a proper roof over the basin so the grandmothers don’t have to stand in the rain. Think of the comfort, Hector. Think of the progress.”

Hector looked at the mud clinging to his boots, then at the blueprints for a grander Oakhaven. He thought of the shivering children in the morning queue. It’s a victimless adjustment, he told himself. The water is literally going to waste in the moonlight. I am merely harvesting what was being lost.

“Very well,” Hector said, his voice steady. “But only for the duration of the crimson order. And the fee must be documented.”

Part III: The VIP System and the Softening of Norms

The path was finished within a month. It was beautiful—level, clean, and bordered by small flowering shrubs imported from the lowlands. The villagers praised Hector as a visionary. They didn’t notice that Varg’s dye-works were now running twenty-four hours a day, or that the small stream trailing away from the village was beginning to turn a sickly, oily shade of violet.

The “Maintenance Fee” proved to be a powerful aphrodisiac for Hector’s ambitions. Soon, other merchants noticed Varg’s increased productivity and his lack of presence in the morning Line. The blacksmith, the brewer, and the head of the tannery all approached Hector with similar offers. They didn’t want to wait; they had “growth” to manage, “contracts” to fulfill, and “contributions” to make to the village’s infrastructure.

Hector found himself in a whirlwind of administrative activity. The simple wooden ladle was replaced by a complex system of brass valves and copper pipes. He created a leather-bound ledger. He hired two assistants, bright-eyed young men from the city, to manage the “Off-Peak Scheduling.” He built a small office next to the spring, tearing down the Elder’s shack to make room for a sturdy timber building with glass windows. He replaced his straw bed with a mattress of goose down and his wooden bowl with fine porcelain.

“I am improving the infrastructure,” he told the village priest when questioned about the new iron-wrought roof over the spring. “The merchants are happy, the economy is booming, and the spring is finally being managed with professional oversight rather than mystical superstition.”

But a strange, quiet thing began to happen to the Spring. The water in the basin, once deep enough to submerge a calf, began to shallow. The pressure from the mountain seemed… tired. The crystalline flow became a sluggish pulse.

In the mornings, the Line grew longer and more fractious. Even though the merchants were gone, the basin took twice as long to refill after the “Night Access” sessions. The villagers, once patient and communal, became irritable. The dawn silence was replaced by the sound of bickering. Neighbors who had known each other for forty years began to accuse one another of “taking too much.” Someone threw a stone at a woman who took too long to fill her jar, and for the first time in Oakhaven’s history, blood was spilled on the stone path.

Hector realized he needed order. He used the “Maintenance Fees” to hire four men from the next town—broad-shouldered men with iron-studded batons and eyes that didn’t know the villagers’ names. They were the “Spring Guard.” Their job was to ensure the Line moved quickly and that no one took more than their “Allotted Share.”

The Allotted Share was a new concept Hector had introduced. It was exactly half of what people used to take.

“Conservation is a civic duty in a growing economy,” Hector announced from his new stone balcony. He was wearing a silk tunic now, a deep indigo gift from Varg’s latest run. He looked every bit the governor, but his heart felt like a tightening knot.

Part IV: The Capture of the Keeper

By the end of the second year, the transformation of Oakhaven was complete. The village was wealthier on paper, but the air felt thin and the people felt brittle. Hector no longer touched the water himself; his assistants brought it to him in a silver pitcher. He spent his days in meetings with “The Consortium”—Varg and the other stakeholders who now controlled the majority of the village’s capital.

One afternoon, the village healer, an old woman named Elara, walked into Hector’s office. She didn’t have a bucket; she had a handful of dead, grey herbs. Her face was a map of disappointment.

“The well in the lower meadow has dried up, Hector,” she said, her voice like cracking parchment. “The Mountain Spring is the only thing left, and the flow is a mere weep against the rock. My patients are thirsty. The babies are getting the fever because their mothers have no water to wash the linens. You must stop the night pumping. You must return us to the Line.”

Hector felt a pang of the old guilt, a ghost of the Elder Keeper’s silent gaze. He looked at the ledgers, then at the old woman. “I will speak to Varg immediately, Elara. We will find a balance.”

That evening, Hector met Varg at the dyer’s villa. The villa was a monument to Varg’s success, filled with velvet tapestries and the smell of expensive spices.

“Varg, we have to cut back,” Hector said, his voice trembling slightly as he stood before the merchant. “The spring is failing. The people are suffering. Elara says the children are sick. I’m suspending all Night Access for thirty days to let the mountain recharge.”

Varg didn’t get angry. He didn’t even stand up. He simply set down his wine and smiled—a slow, predatory expression.

“Hector, my dear boy, let’s look at the reality of our situation,” Varg said, gesturing to the opulent room. “My ‘Maintenance Fees’ pay for your Spring Guard. They pay for your assistants. They pay for the very roof over the Spring and the silk on your back. If I stop production, I stop paying. If I stop paying, you have to fire the guards tomorrow. Do you think those people in the Line—those hungry, thirsty, angry people—will be grateful? No. They have been watching you get fat while they get thin. Without those guards, they will tear you apart before the sun sets.”

Varg leaned in, the smell of lye and power overpowering the incense. “You aren’t the Keeper anymore, Hector. You’re the Manager of an asset. And a manager’s primary job is to keep the shareholders happy. I’ve already paid for next month’s water in advance. The gold is already in your ledger. You can’t return it; you’ve already spent it on the new irrigation pipes for the Blacksmith’s industrial forge.”

Hector looked at his hands. They were clean, manicured, and soft. He realized with a sickening jolt that he was no longer a public servant. He was a captive of the very system he had built to “save” the village. He was an employee of the man who was draining the village dry.

Part V: The Summer of Dust and Rage

The drought came in the third year, as if the mountain itself had decided to withhold its heart. It was a brutal, relentless sun that turned the Oakhaven valley into an oven of scorched grass and cracked earth. The Mountain Spring, once a roaring pulse of life, was now a pathetic, salt-rimmed weep against the granite.

The Line disappeared. There was no point in waiting for water that didn’t come. The dawn silence was now filled with the sound of dust blowing against dry wood.

The villagers gathered in the square, their faces hollow, their eyes burning with a mixture of dehydration and a long-simmering rage. They marched toward the spring, a ragged army of the parched. They saw the roofed pavilion, the paved paths, and the four guards standing with their batons, looking well-hydrated and indifferent.

Hector stood on his balcony, looking down at his neighbors. He saw the baker who had given him extra bread as a boy. He saw the children he had promised to bring into “the future,” their lips cracked and white.

“Open the gate!” the crowd roared. The sound was like the growl of a dying animal. “Give us the water!”

Hector turned to look inside his office. Varg was there, sitting in Hector’s chair, picking his teeth with a silver splinter. Two of the guards were standing by the door, their loyalty bought and paid for by Varg’s “bonuses.”

“The gate stays closed,” Varg said, not even looking up. “My vats are half-full of a very expensive indigo run for the Southern Isles. If the water stops now, the silk is ruined. I have a legal contract for that water, Hector. I’ve paid for it. It belongs to the Varg Dye-Works.”

“They’re going to kill me, Varg,” Hector whispered, his back to the window.

“The guards won’t let them,” Varg replied calmly. “As long as they’re paid. And I just gave them enough to buy their own farms in the river lands once this is over. Just do your job, Manager.”

Hector walked back to the edge of the balcony. He looked at the angry mob. He thought about the Elder Keeper’s shack. He thought about the free water and the long, slow, honest Line. He opened his mouth to tell the guards to stand down, to let the people drink what was left.

But then he looked at the iron-studded batons. He looked at the gold coins glinting on his desk. He looked at the comfort he had become addicted to, and the fear that had become his shadow.

“Disperse!” Hector cried out, his voice breaking into a shrill, desperate pitch. “The water is private property by legal contract! Any attempt to approach the basin will be treated as a criminal act! For the sake of the village’s economy, go home!”

The riot was short and bloody. The guards were well-fed and strong; the villagers were weak with thirst. By sunset, the beautiful grey stone path was stained, not with indigo or crimson, but with the dark, iron-scented blood of the people Oakhaven was supposed to sustain.

Part VI: The Breaking of the Heart

Varg was impatient. The trickle from the rock wasn’t enough to finish his indigo run, and the deadline for the Southern Isles was approaching. That night, while the village wept in the dark and the smell of smoke from small, desperate fires hung in the air, Varg brought a team of professional miners from the city.

“The water is trapped behind the silt and the rock,” Varg commanded, pointing to the heart of the basin. “The mountain is being stingy. Dig into the basin. Scrape the bottom. Increase the flow by force. If we can’t have the stream, we’ll take the vein.”

Hector watched from his window, paralyzed by a mounting dread. He knew the mountain’s lore, even if he had dismissed it as myth. He remembered the Elder Keeper saying the “silt was the seal,” that the basin was a living thing that must never be pierced.

The miners hammered and picked. They used steel drills and heavy sledges. They scraped away the ancient clay and the deep, compacted minerals that had held the water in its course for millennia. Hector heard the sound of the mountain being violated—a high, screeching protest of stone against steel.

Suddenly, there was a loud, hollow thud—the sound of a giant drum being struck deep underground. The earth beneath the spring shuddered.

The trickle didn’t increase. It stopped entirely.

The miners had cracked the natural clay seal and the limestone shelf of the spring. The water didn’t flow out toward the village; it found a new path, a vertical rift in the rock created by the aggressive, desperate digging. Hector watched in horror as the last few gallons of water in the basin swirled like a drain and vanished into the dark, unreachable bowels of the mountain.

The Mountain Spring was dead. Varg had tried to own it, and in doing so, he had murdered it.

Part VII: The Golden Grave

The exodus began two days later. Without water, Oakhaven was no longer a village; it was a collection of hot stones and broken dreams. The villagers packed what they could carry—a few clothes, some dry grain—and began the long, staggering trek toward the distant river lands.

Varg was among the first to leave. He had his remaining dyes and fine silks packed onto sturdy wagons with reinforced wheels. He had lost his indigo run, but he had enough capital in city banks to start again. He didn’t look back at the village. To him, Oakhaven was a used-up tool, a broken gear in a machine that had served its purpose. He was a man of the future, and the future had no room for ghost towns.

Hector stayed. He found he couldn’t leave. He sat in his beautiful timber office, surrounded by ledgers that recorded a wealth that no longer existed and gold coins that could buy nothing. The Spring Guard had vanished as soon as the last chest of gold was emptied, taking Hector’s silver service and his porcelain bowls with them as “severance.”

He walked out to the basin. The roof was still there, a mocking canopy over a dry hole. He knelt on the blood-stained stone path and reached into the darkness where the water used to be. He found only dry dust, the smell of burnt stone, and the silence of a tomb.

He climbed up to the balcony of his office and looked out over the empty village. The sun was setting, casting a long, golden light over the ruins of his “efficiency.” The paved path led nowhere. The shrubs were dead. The glass windows of his office reflected a world that had vanished.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a handful of Varg’s gold coins. They were heavy, shiny, and beautifully minted. He held them up to the setting sun.

He tried to swallow, but his throat was a parched desert. His tongue felt like a piece of dry leather. He realized the final, absolute truth that the Elder Keeper had known in his silence, a truth that no city education could teach.

You can’t drink gold.

Hector sat in the dust where the Elder Keeper’s shack had once stood, clutching his useless wealth, waiting for a rain that would never come. He was the last resident of a town that had traded its life for a paved path, the Keeper of a spring that had finally, mercifully, gone to sleep.

Lessons from the Fall of Oakhaven

If you’ve finished the story of Hector and the Mountain Spring, you’re probably left with a bit of a dry throat and a lot of questions. How did a smart, educated guy like Hector end up sitting on a pile of gold in a dead village? Why didn’t the villagers stop him sooner? And why does this story feel so uncomfortably familiar in our modern world?

The story of Oakhaven is a mirror. It reflects the way we manage our resources, our businesses, and our governments. Let’s break down the major “lightbulb moments” from the story and see how they apply to the world outside the pages.

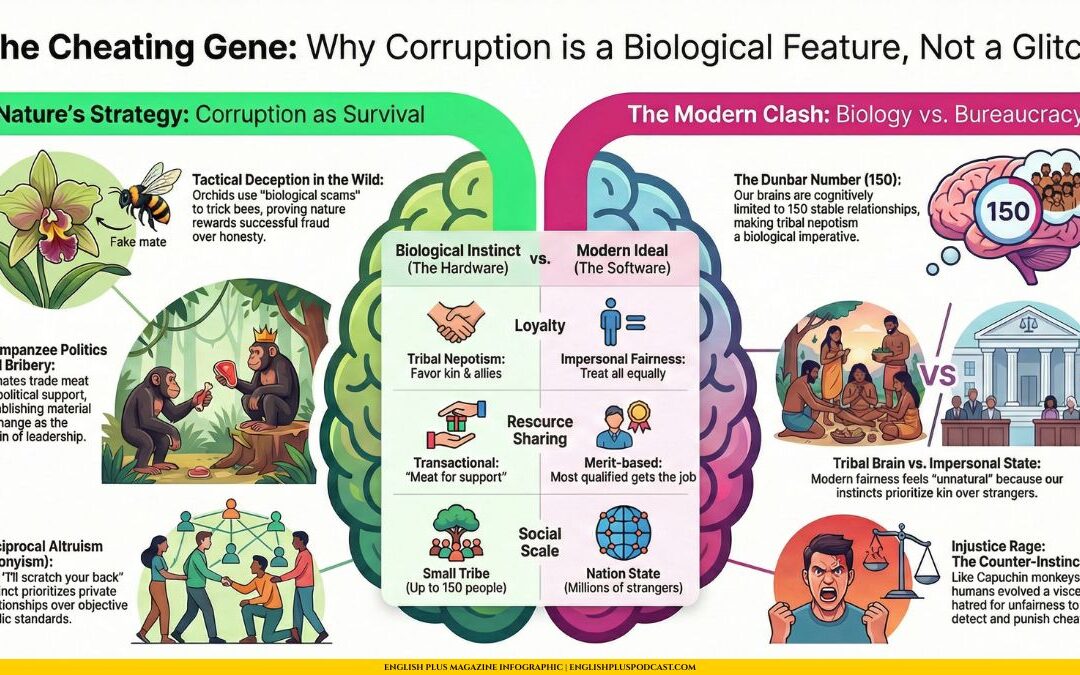

1. The “Better” Trap: Efficiency vs. Resilience

When Hector took over, his first goal wasn’t to destroy the village—it was to make it “better.” He saw the long line at the spring as a waste of time. In modern business speak, he was looking for “efficiency.” The problem is that in many systems, the “inefficiency” is actually a feature, not a bug. The “Line” in Oakhaven wasn’t just a queue; it was a social equalizer. Because everyone had to wait, everyone was equal. By introducing “Night Access” for a fee, Hector prioritized speed over stability.

The Lesson: In our own lives and organizations, we often try to optimize everything for speed or profit. But when you remove the “friction” (like the time spent in the line), you often remove the very thing that keeps the community together. Efficiency makes a system go faster, but resilience is what keeps it from breaking when things get tough.

2. The Slippery Slope of “Victimless” Compromise

Hector’s first mistake was letting Varg come at night. He told himself it was “victimless” because the water was just spilling away anyway. This is the classic Slippery Slope. Corruption rarely starts with a villain twirling their mustache. It starts with a “reasonable” exception. “It’s just for one order,” Hector said. “It helps the economy,” he said. But every time you make an exception for a “VIP,” you erode the rule of law for everyone else. By the time the villagers realized they were getting less water, the system had already shifted from a public trust to a private business.

The Lesson: Watch out for “just this once” logic. In ethics, this is called Incrementalism. If you wouldn’t be okay with everyone doing it, don’t let the first person do it.

3. Understanding “Regulatory Capture”

This is perhaps the most important takeaway for anyone interested in politics or business. Regulatory Capture is a fancy term for what happened when Varg told Hector, “You aren’t the Keeper anymore, you’re the Manager.”

Hector was supposed to regulate the spring for the benefit of the people. But because he became dependent on Varg’s “Maintenance Fees” to pay his guards and buy his silk tunics, he was “captured.” He could no longer say “no” to Varg because Varg held the purse strings.

The Lesson: When the person meant to watch the industry becomes the industry’s best friend (or employee), the public loses. This happens in the real world with banking regulators, environmental agencies, and even social media moderators. Always ask: Who is paying the person in charge, and what happens if they say “no”?

4. The Tragedy of the Commons

The Spring is what economists call a Common-Pool Resource. The “Tragedy of the Commons” happens when individuals act in their own self-interest and end up destroying the resource for everyone.

Varg wasn’t “evil” in his own mind; he was just a businessman trying to fulfill a contract. The blacksmith just wanted to forge more tools. But because there was no one left to say, “Stop, the mountain can’t handle this,” they collectively drained it. They were so focused on their individual slices of the pie that they forgot the oven was on fire.

The Lesson: We see this today with overfishing, climate change, and even office refrigerators. If everyone takes “just a little more” than their share, the whole system collapses.

5. Goodhart’s Law: When the Measure Becomes the Target

There’s an old saying in economics: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Hector’s “measure” of success shifted from “Is the village hydrated?” to “How much is in the ledger?” Because he was focused on the gold (the measure), he lost sight of the water (the reality). By the end, he had achieved his target (maximum gold) but failed his mission (keeping the village alive).

The Lesson: Be careful what you measure. If you only reward salespeople for “number of calls,” they’ll make a lot of useless calls. If you only measure a country by its GDP, you might ignore the fact that its “Spring” is drying up.

6. The Hubris of Optimization

The most painful part of the story is the mining of the spring. Varg and Hector thought they could “force” the mountain to give more. They treated a delicate, natural ecosystem like a vending machine.

They didn’t respect the Complexity of the system. They thought they understood how the spring worked, but they didn’t. They broke the “seal” (the silt), and once a complex system is broken, you can’t just glue it back together.

The Lesson: We often think we can “fix” complex problems with brute force or simple technology. Whether it’s the environment or a corporate culture, some things are “emergent”—they exist because of a delicate balance. If you poke it too hard to get more “output,” you might lose the “input” forever.

The Plunge

There is a profound, almost musical rhythm to the way this story opens, and stepping into its world feels like dunking your face into the very mountain spring it describes: shocking, clarifying, and pure. The text invites us not just to observe Oakhaven, but to stand in it. We can feel the cold, “liquid silver” slipping through our fingers. We can see the deep, ancient green of the emerald moss clinging to the stone basin. The story doesn’t just tell us that water is important; it paints water as the master conductor of the village’s entire existence.

The beauty of the narrative lies in its sharp contrasts. In the beginning, there is a deep reverence for the natural world. The Elder Keeper isn’t described as a manager or a boss; he is an extension of the mountain itself. He is weathered shale and high-altitude lakes. He embodies a kind of monastic stillness that feels incredibly rare in our modern, frantic world. And then there is the Line. The Line is perhaps the most beautiful concept in the early paragraphs. It’s an equalizer. In a world that is always trying to sort us into hierarchies of rich and poor, important and unimportant, the morning queue for water strips all that away. The rich merchant and the stable hand are just thirsty people waiting their turn. The time spent waiting isn’t wasted; it’s the very glue that holds the village together. It’s where life happens—where disputes are settled, where grief is shared, where humanity is affirmed.

But the story shifts, and the beauty of the prose shifts with it, becoming sharper, faster, and distinctly more metallic. When Hector arrives, the language turns from natural elements—stone, moss, water, linen—to the language of the industrial and the bureaucratic. We start hearing about blueprints, efficiency, velocity, and maintenance fees. The sensory experience of the story changes from the pure, scentless mountain air to the smell of lye, the clinking of brass valves, and the sight of oily violet runoff.

It is fascinating to watch how the narrative captures the slow seduction of convenience. The new stone path is nice. The iron roof does keep the rain off. The story is honest enough to admit that progress is attractive. We understand why the villagers initially cheer for Hector. Who wouldn’t want to skip the mud and the waiting? But as the text pulls us deeper, it reveals the rot beneath the shiny new infrastructure. The beauty of the water—its unhurried, generous flow—is strangled by copper pipes and ledgers. The water stops being a gift and becomes an “asset.”

By the time the climax arrives, the story has built a feeling of suffocating dread. The mountain, which felt so alive and giving in the first few paragraphs, begins to feel tired, then angry, and finally, violated. The auditory details are haunting: the screeching of steel against stone, the hollow, drum-like thud deep underground. The story makes us feel the exact moment the earth’s heart breaks.

And then, the ending. It strips away all the noise of the middle chapters—all the talk of consortiums and allotted shares and legal contracts—and leaves us in a devastating silence. The image of a man sitting alone in the dust of his own “success,” holding heavy, beautifully minted gold coins that cannot quench his thirst, is a powerful visual echo of the entire narrative. It’s a beautifully written tragedy that holds a mirror up to our own society, asking us to look closely at what we are trading for our comforts, and reminding us that no amount of polished brass can replace the simple, life-giving miracle of the natural world.

Let’s Roll Up Our Sleeves

Let’s dive into the mechanics, meaning, and mastery of “The Keeper of the Spring.” We’re going to break down the narrative so you can see exactly how the author built this tragic, beautiful fable.

Summary

Part I: The story introduces Oakhaven, a village entirely dependent on a single Mountain Spring. The spring flows at a constant rate, forcing the villagers to wait in a daily, egalitarian “Line” to collect their daily water. The spring is guarded by the Elder Keeper, a silent, naturalistic figure who enforces the Law: “Take what you need for the day, and no more.” The water is free, costing only time, and the Line serves as the social foundation of the village. The Elder Keeper eventually dies, leaving the younger generation eager for a more “modern” approach.

Part II: Hector, a young, educated man, is appointed as the new Keeper. He promises efficiency and progress. Initially, he improves the infrastructure, building a clean path. However, Varg, an ambitious merchant and dyer, convinces Hector to allow “Night Access” to the spring in exchange for a “Maintenance Fee.” Hector rationalizes this as harvesting wasted water to fund village improvements.

Part III: The new system brings apparent wealth and aesthetic improvements, but the village’s social fabric begins to tear. More merchants buy into the “Off-Peak Scheduling.” Hector becomes an administrator, surrounded by ledgers and luxury. The spring’s flow begins to weaken. The morning Line becomes chaotic and violent as water becomes scarce. To maintain order, Hector hires out-of-town mercenaries, the “Spring Guard,” and cuts the villagers’ water rations in half under the guise of “conservation.”

Part IV: The village is suffering. Elara, the healer, confronts Hector about the dying spring and sick children. Hector, feeling a pang of guilt, tries to pause Varg’s night operations. However, Varg ruthlessly explains that Hector is no longer a Keeper, but a captive Manager. The village’s infrastructure—and Hector’s luxurious lifestyle and guards—are entirely dependent on Varg’s money. Hector realizes he is trapped by the system he built.

Part V: A severe drought hits, and the spring dwindles to a trickle. The desperate, thirsty villagers march on the spring, demanding water. Hector, terrified of the mob and manipulated by Varg (who claims the remaining water via legal contract), orders the guards to disperse the crowd. A bloody riot ensues, and the villagers are beaten back, their blood staining the paved path.

Part VI: Desperate to finish his order, Varg brings in miners to forcefully extract water from the mountain’s basin. Ignoring the ancient lore that the basin’s silt is a natural seal, they drill into the stone. The mountain fractures, and the spring drains away into the deep earth. Varg’s greed ultimately murders the spring.

Part VII: The village is destroyed. The villagers, including Varg with his remaining wealth, abandon Oakhaven. Hector is left entirely alone. His guards abandon him, taking his luxuries. He sits in the dry dust holding Varg’s gold coins, realizing the ultimate, tragic lesson: wealth is meaningless without life-giving resources. “You can’t drink gold.”

Themes

1. Tradition vs. Modernity (The Illusion of Progress)

The story deeply questions what “progress” actually means. The Elder Keeper represents tradition—slow, natural, and sustainable. Hector represents modernity—fast, administrative, and capitalistic. Hector’s improvements (stone paths, copper pipes, ledgers) look like progress, but they ultimately distance the community from the source of their life and from each other. The story suggests that modern efficiency often destroys the very things it seeks to manage.

2. The Tragedy of the Commons and the Corrupting Nature of Greed

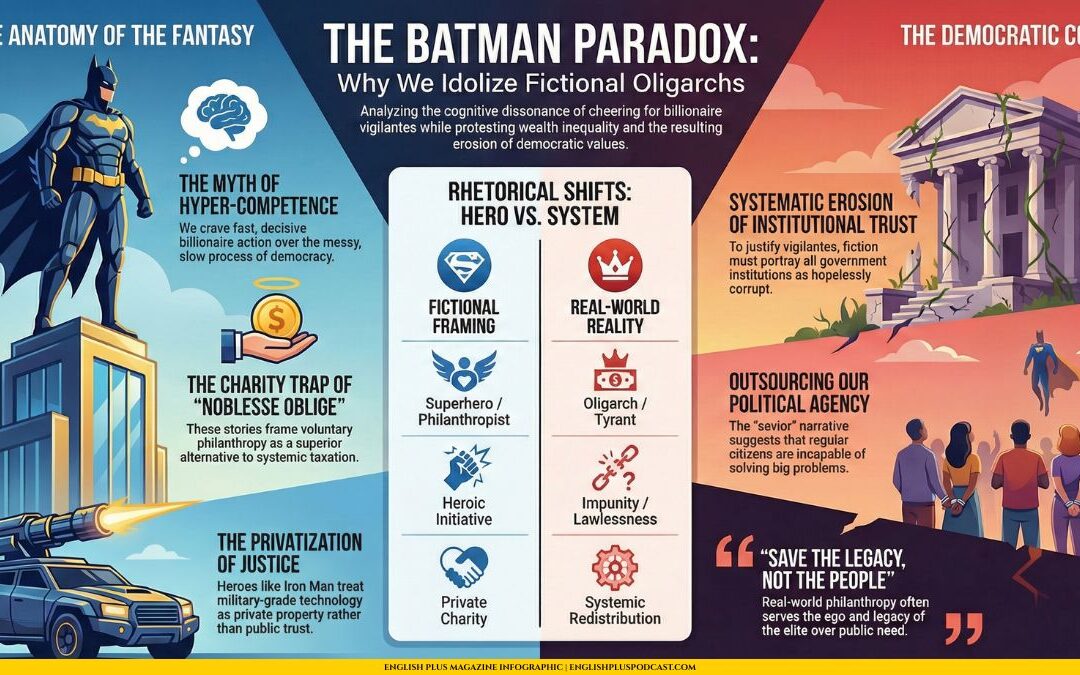

The spring is a classic “commons”—a shared resource. When it was governed by simple, equitable rules (take what you need), it sustained everyone. When Varg introduces the concept of buying extra access for personal profit, the system collapses. Greed is depicted not as a cartoonish evil, but as a creeping, logical-sounding rot (“think of the comfort,” “the velocity of money”). Varg’s greed, facilitated by Hector’s ambition, drains the community dry.

3. The Commodification of Nature

Initially, the water is a sacred gift from the mountain. By the end, it is “private property by legal contract.” The story highlights the danger of reducing nature to an “asset” on a ledger. When nature is viewed only as a resource to be optimized and exploited, it rebels and breaks.

4. Community vs. Individualism

The Line represents community. It levels social status and forces interaction. When the merchants are allowed to bypass the Line, the community fractures. The shared struggle is replaced by an “every man for himself” mentality, leading directly to violence and resentment.

Characters

The Elder Keeper:

He is the embodiment of the mountain and ancient wisdom. He is silent, immovable, and uncorrupted by material desires. He doesn’t manage the spring; he serves it. His death marks the end of Oakhaven’s innocence and sustainability.

Hector (The Architect of Progress):

The tragic protagonist. Hector is not initially evil; he is idealistic but naive. He is seduced by the idea of making things “better” and easier. His fatal flaw is hubris—believing he can manage nature better than nature can manage itself. He trades his moral authority for comfort and eventually becomes a powerless puppet to corporate interests.

Varg (The Master Dyer):

The antagonist. Varg represents unchecked capitalism and industrialization. He is smooth, manipulative, and entirely devoid of empathy. He views everything—water, people, even Hector—as tools for profit. He is the only character who successfully escapes the tragedy he causes, reflecting the harsh reality that those who exploit resources often avoid the consequences of their actions.

Elara (The Healer):

She represents the conscience of the village and the reality of the ground level. While Hector looks at ledgers, Elara looks at sick children. She is the voice attempting to pull Hector back to reality before it’s too late.

The Mountain / The Spring:

Functionally, the mountain is a character. It has a “rhythm,” a “pulse,” and a “heart.” It is generous when respected but fragile when exploited. Its final destruction is described as a murder, emphasizing its living nature.

Important Moments and Lines

“Take what you need for the day, and no more.”

The core philosophy of the story. It is a mandate of sustainability and trust. It assumes the mountain will provide again tomorrow, so hoarding is unnecessary.

“The Line was the great leveler of Oakhaven society.”

This highlights how shared burdens create equality. Time is the only currency that matters in the old system, and everyone has the same 24 hours.

“The Law was written by a man who didn’t understand the velocity of money,” Varg whispered.

Varg’s introduction of economic rhetoric into a natural ecosystem. It marks the exact moment the village’s values shift from survival and community to profit and speed.

“You aren’t the Keeper anymore, Hector. You’re the Manager of an asset.”

The turning point for Hector. Varg strips away Hector’s illusions of leadership. A Keeper protects something sacred; a Manager exploits something for shareholders.

“He realized the final, absolute truth… You can’t drink gold.”

The devastating climax. It is a blunt, profound realization that artificial wealth (money/gold) has absolutely no intrinsic value when fundamental biological needs (water/nature) are destroyed.

Why You Should Read It

“The Keeper of the Spring” is a masterclass in allegorical storytelling. It takes complex, global issues—climate change, wealth inequality, the privatization of natural resources, and the loss of community—and distills them into a gripping, emotional narrative about a single village. It forces the reader to ask uncomfortable questions about their own society. Are we waiting in the Line, or are we paying for Night Access? It’s a beautifully written, harrowing tale that will stay with you long after the final drop of water is gone. It reminds us that literature isn’t just about escaping reality; sometimes, it’s the best tool we have for understanding it.

Vocabulary in Context: Words from the Mountain

Great literature doesn’t just tell a story; it introduces us to words that carry weight, history, and profound meaning. “The Keeper of the Spring” uses specific, evocative language to paint the contrast between the natural world and the industrial one.

Here are 12 powerful words from the story to add to your own vocabulary toolkit.

1. Crystalline (Adjective)

- Definition: Strikingly clear or sparkling; having the structure and form of a crystal.

- In the Story: “It was a crystalline vein that pulsed from the granite heart of the peak above…”

- In Everyday Life: “After the heavy rain, the lake was so crystalline that you could see the pebbles on the bottom.”

2. Monastic (Adjective)

- Definition: Resembling the simple, secluded, and strictly disciplined life of monks or nuns.

- In the Story: “His life was one of monastic simplicity; he owned two shirts of coarse linen, a bed of straw, and a single wooden ladle.”

- In Everyday Life: “To finish writing her novel, she retreated to a cabin in the woods and lived a monastic lifestyle for three months.”

3. Egalitarian (Adjective)

- Definition: Believing in the principle that all people are equal and deserve equal rights and opportunities.

- In the Story: “It was a slow, egalitarian crawl. The rich merchant stood behind the stable hand…”

- In Everyday Life: “The tech startup prided itself on its egalitarian culture, where the CEO and the interns all worked at the same big table.”

4. Fester (Verb)

- Definition: To become worse or more intense, especially through long-term neglect or indifference (often applied to wounds or negative feelings).

- In the Story: “They shared news of births and deaths, negotiated the price of grain, and settled disputes before they could fester.”

- In Everyday Life: “Because they never talked about the misunderstanding, the resentment continued to fester between the two friends.”

5. Sentinel (Noun)

- Definition: A soldier or guard whose job is to stand and keep watch.

- In the Story: “The Elder Keeper stood at the head of the Line, a silent sentinel.”

- In Everyday Life: “The tall pine tree at the edge of the property stood like a sentinel, watching over the old farmhouse.”

6. Quagmire (Noun)

- Definition: Literally, a soft boggy area of land that gives way underfoot; figuratively, an awkward, complex, or hazardous situation.

- In the Story: “He noticed the path leading to the spring was a quagmire during the rainy season, a source of constant complaint.”

- In Everyday Life: “The project turned into a legal quagmire when three different companies claimed they owned the copyright.”

7. Stipend (Noun)

- Definition: A fixed regular sum paid as a salary or allowance.

- In the Story: “Using his own meager stipend, he hired a few laborers to lay down flat, grey stones…”

- In Everyday Life: “The university offers a monthly stipend to graduate students to help cover their living expenses.”

8. Fractious (Adjective)

- Definition: Irritable, quarrelsome, or difficult to control.

- In the Story: “In the mornings, the Line grew longer and more fractious.”

- In Everyday Life: “The children became fractious and cranky after sitting in the hot car for four hours.”

9. Consortium (Noun)

- Definition: An association, typically of several business companies, formed to undertake an enterprise beyond the resources of any one member.

- In the Story: “He spent his days in meetings with ‘The Consortium’—Varg and the other stakeholders who now controlled the majority of the village’s capital.”

- In Everyday Life: “A consortium of local businesses donated the funds to build the new community center.”

10. Parched (Adjective)

- Definition: Dried out with heat; extremely thirsty.

- In the Story: “They marched toward the spring, a ragged army of the parched.”

- In Everyday Life: “After hiking all afternoon in the summer sun, I was absolutely parched.”

11. Severance (Noun)

- Definition: The action of ending a connection or relationship; officially, pay and benefits an employee receives when they leave employment.

- In the Story: “…taking Hector’s silver service and his porcelain bowls with them as ‘severance.'” (Note: The story uses this ironically, as the guards are stealing the items as their “pay” for leaving!)

- In Everyday Life: “When the company downsized, they offered the affected workers a generous severance package.”

12. Exodus (Noun)

- Definition: A mass departure of people, especially emigrants.

- In the Story: “The exodus began two days later.”

- In Everyday Life: “As soon as the final bell rang, there was a massive exodus of students heading for the doors.”

Join the Conversation: Food for Thought

Great stories don’t end when the ink dries; they live on in the conversations we have about them. Now that we’ve taken a deep dive into Oakhaven, I’d love to hear your perspective.

Grab a journal, discuss these with a friend, or drop your thoughts in the comments below!

1. The Modern “Mountain Spring”

In the story, the Mountain Spring is a shared resource that gets exploited for private gain. What is a real-world equivalent of the Mountain Spring today? Are there “commons” in our society that are currently being drained by a modern-day Varg?

2. The Villain Question

Is Hector actually a villain? He starts with good intentions—wanting to save people time and build better infrastructure. At what specific moment do you think he crossed the line from a naive public servant to a corrupt manager?

3. The True Cost of “Night Access”

Varg convinces Hector to let him bypass the line by selling the idea of convenience and efficiency. In our own lives, what do we trade for convenience? Are there modern technologies or services that give us “Night Access” but secretly erode our communities?

4. “You Can’t Drink Gold”

The final line of the story is a devastating realization about the limits of wealth. In an era where so much of our life is digital and focused on accumulating numbers on a screen, how can we make sure we don’t end up like Hector—surrounded by “gold” but completely parched?

5. Rewrite the Ending

Imagine Elara the healer had successfully convinced Hector to shut down the Night Access when she visited his office. How would the story have unfolded? Would the village have survived, or would Varg have found another way to take control?

Diving Deeper: Want to Learn More?

If these themes resonated with you, there is a wealth of fascinating material to explore. Here are some starting points to “keep your own spring” healthy:

1. Read: “Governing the Commons” by Elinor Ostrom

If you want to know how Oakhaven could have been saved, look at the work of Elinor Ostrom. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics for showing that the “Tragedy of the Commons” isn’t inevitable. She found that when local communities (like the Oakhaven villagers) are allowed to make their own rules and monitor each other (like the Elder Keeper), they can manage resources for centuries.

2. Explore: The Concept of “Chesterton’s Fence”

This is a philosophical principle that says you should never tear down a fence until you understand why it was built in the first place. Hector tore down the “inefficient” Line and the “mossy” basin without understanding their purpose.

3. Research: Real-World Regulatory Capture

Look up the history of the 2008 Financial Crisis or the Boeing 737 Max story. In both cases, the relationship between the “Keepers” (regulators) and the “Merchants” (industry) became too close, leading to systemic failures that look a lot like the drought in Oakhaven.

4. Think About: The “Resource Curse”

In geopolitics, countries with the most natural resources (like oil or gold) often have the most corruption and the least stability. Why? Because the “Hectors” of those countries stop caring about the people and start focusing only on the “Vargs” who pay for the resource.

Final Reflection

The story ends with Hector realizing he “can’t drink gold.” It’s a stark reminder that capital is not the same as value. Gold is a representation of value, but water is value.

In your own work, in your community, and in your life, take a look at the “Springs” you are responsible for. Are you guarding the water, or are you just counting the coins? The “Elder Keepers” of the world may live in shacks, but they leave behind villages that thrive for a thousand years. The “Hectors” of the world build paved paths that lead to nowhere.

Which one will you be?

Take Your Learning Further

Did you enjoy this deep dive into the hidden layers of literature? If you love exploring the beauty of words, the power of storytelling, and the lessons we can carry into our daily lives, there is so much more waiting for you.

Join our growing community on Patreon! Whether you want to jump into the Learner/Reader levels for exclusive educational content and writing guides, or step up to a Sponsor level to directly support the creation of these deep dives, there is a place for you. Let’s keep the conversation going!

0 Comments