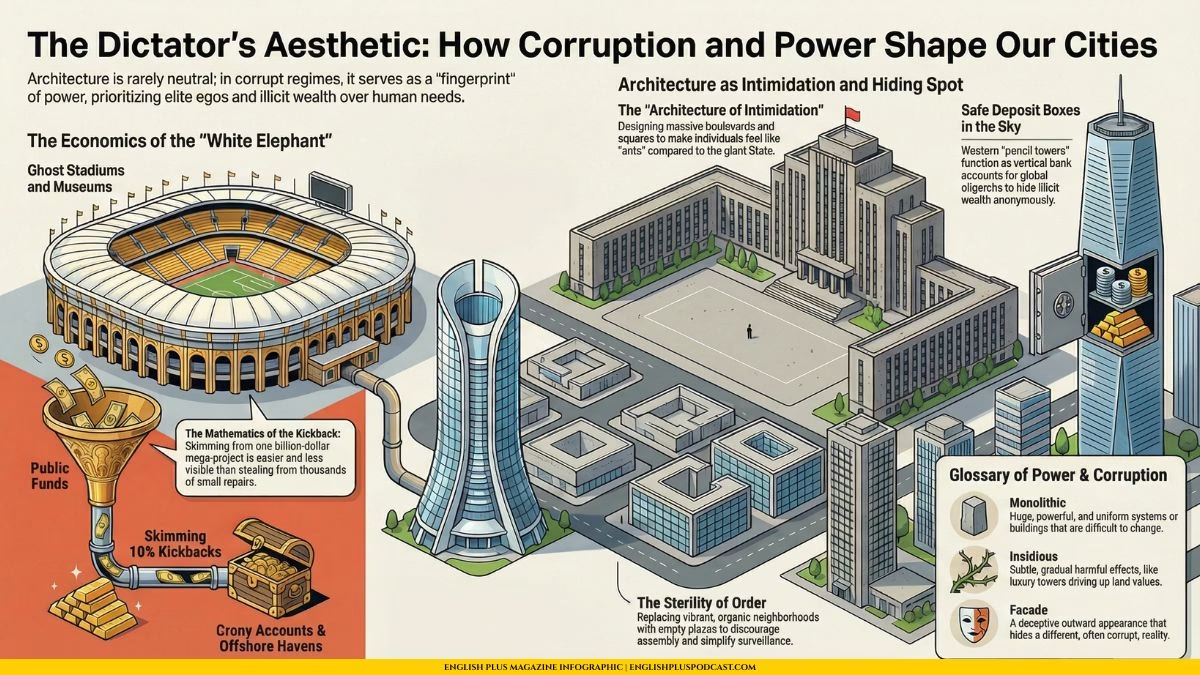

- The “White Elephant” Phenomenon: The Economics of the Mega-Project

- The Architecture of Intimidation: Design as Control

- Real Estate as a Bank Account: The Western Oligarchy

- Reading the City

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis: Playing Devil’s Advocate

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Baron

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

There is a specific feeling you get when you stand in the center of a city built not for people, but for an ego. It is a sense of displacement, a subtle unease that creeps in when the scale of the surroundings refuses to acknowledge your humanity. You look up at a monolithic structure that scrapes the sky, or you walk down a boulevard so wide it feels less like a street and more like a runway for tanks, and you realize something fundamental: this was not built for you.

We often talk about corruption in terms of numbers—digits in an offshore bank account, percentages lost from GDP, or the unseen handshake in a smoke-filled room. But corruption is rarely invisible. In fact, it is often the most visible thing in the landscape. It leaves a fingerprint in concrete, steel, and glass. From the marble-clad insanity of Ceaușescu’s Bucharest to the needle-thin, empty towers piercing the clouds of Midtown Manhattan, money laundering and authoritarian power have a distinct architectural style. Let’s call it “The Dictator’s Aesthetic.”

This isn’t just about bad taste—though, let’s be honest, despots have a historic affinity for gold leaf and velvet that would make a Vegas casino owner blush. This is about architecture as a weapon, a vault, and a lie. When we look at the skyline, we are reading a story of power. And lately, the story is a tragedy.

The “White Elephant” Phenomenon: The Economics of the Mega-Project

If you want to understand how a kleptocracy functions, you have to stop looking at small thefts and start looking at giant buildings. There is a common misconception that corrupt politicians steal by taking a little bit from the maintenance budget of a hundred schools. While that certainly happens, it is inefficient. It requires too much paperwork, too many accomplices, and too much visibility.

No, if you want to steal real money, you build a stadium. Or an international airport for a province with no tourists. Or a bridge to nowhere.

The Mathematics of the Kickback

The logic is brutally simple. It is infinitely easier to skim ten percent off a billion-dollar mega-project than it is to steal from a thousand small repair jobs. This is why you see “White Elephants”—massive, impressive, and utterly useless structures—dominating the landscapes of corrupt regimes.

These projects serve a dual purpose. Ostensibly, they are symbols of progress. The ribbon-cutting ceremony provides a photo op where the leader can point to the steel skeleton and say, “Look, I am modernizing the nation.” But beneath the surface, the project is a funnel. The construction contracts are awarded to cousins, cronies, or shell companies. Materials are invoiced at triple their market value. The cement is diluted; the steel is lower grade. The difference in cost goes straight into a private account in the Cayman Islands.

The Ghost Stadiums

Consider the legacy of recent World Cups or Olympic Games hosted in nations with, shall we say, flexible approaches to human rights and fiscal transparency. We see stadiums built with capacities that exceed the population of the towns they are located in. A few years after the games, the grass is dead, the seats are sun-bleached, and the parking lots are empty. They were never meant to be used; they were meant to be built. The transaction was the point, not the utility.

This creates a cityscape of ghosts. We end up with convention centers that host no conventions and museums with no collections. These buildings are monuments to the transfer of wealth from the public purse to private pockets. They sit there, decaying slowly, a physical reminder that the public good was sold off for parts.

The Architecture of Intimidation: Design as Control

While the White Elephant is about theft, the layout of the authoritarian city is about fear. There is a psychological component to urban planning that dictators understand intuitively. If you want to control a population, you must make them feel small. You must design the space so that the individual feels insignificant against the might of the state.

The Wide Boulevard and the Tiny Human

Think of the vast squares in Pyongyang or the terrifyingly wide avenues of Soviet-era Moscow. These spaces are not designed for strolling, window shopping, or bumping into a neighbor. They are hostile to pedestrian life. The scale is intentional. When you stand in a square that is five hundred meters wide, surrounded by government buildings that loom like fortresses, your brain receives a very specific signal: You are an ant. The State is a giant.

This is the architecture of intimidation. It discourages assembly—or rather, it allows for only one type of assembly: the state-sanctioned military parade. These boulevards are designed to accommodate tanks, not café tables. They create sightlines that allow for easy surveillance. There are no cozy corners, no hiding spots, no organic chaos where a revolution might brew over coffee.

The Sterility of Order

Corrupt regimes are obsessed with a specific type of sterility. They mistake cleanliness for order and silence for peace. You often see this in the sudden “beautification” projects where vibrant, albeit messy, neighborhoods are bulldozed to make way for gleaming, empty plazas.

This erasure of the organic city is a tragedy. A healthy city is a bit messy; it has layers of history, winding streets, and a mix of old and new. The authoritarian city wipes the slate clean. It imposes a grid that looks good from a helicopter but feels soulless on the ground. It is a denial of the complexity of human life, replaced by a brutalist simplicity that says, “We have everything under control.”

Real Estate as a Bank Account: The Western Oligarchy

Now, before we get too comfortable thinking this is only a problem for “other” countries—dictatorships in far-off lands—we need to turn our gaze to New York, London, Vancouver, and Miami. Corruption has a passport, and it loves to travel. In the West, the Dictator’s Aesthetic has morphed into something sleeker, glassier, and arguably more insidious: the luxury “pencil tower.”

The Safe Deposit Box in the Sky

Walk through certain neighborhoods in London or look at the Billionaires’ Row in Manhattan. You will see needle-thin skyscrapers, marvels of engineering, rising thousands of feet into the air. They are beautiful, in a cold, crystalline way. But if you look at them at night, you will notice something unsettled: the lights are off. Nobody is home.

These apartments are not homes. They are safe deposit boxes. For the global oligarchy, real estate in stable Western democracies is a currency. If you have illicit wealth—money skimmed from the oil fields, bribes from construction projects, or proceeds from organized crime—you cannot just put it in a regular bank. Banks have compliance departments.

Instead, you buy a fifty-million-dollar penthouse. It is distinct from other assets because it holds value, it is relatively liquid, and thanks to opaque LLC laws, you can own it anonymously. The building itself becomes a physical manifestation of laundered money.

The Zoning of Exclusion

This phenomenon distorts our cities just as much as the dictator’s boulevard. It drives up land values, pushing actual residents out of the city center. It turns vibrant neighborhoods into ghost towns of glass, populated only by doormen guarding empty lobbies.

It creates a visual hierarchy where the most prominent spots in the skyline are reserved for people who don’t even live there. The skyline of New York used to be defined by commerce and industry—the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building. Now, it is defined by private wealth looking for a place to hide. These towers are the “White Elephants” of capitalism—technologically impressive, astronomically expensive, and socially useless.

Reading the City

We need to learn to read our cities. We need to look past the shiny facades and the ribbon-cutting ceremonies. When we see a massive project that defies economic logic, we should ask: Who got the contract? When we see a public square that makes us feel small and exposed, we should ask: Who is this designed to control? And when we see a tower of dark windows, we should ask: Whose money is hiding up there?

Architecture is the physical language of society. Right now, in too many places, that language is speaking of greed, ego, and domination. But the city belongs to the people who live in it, not the people who plunder it. Recognizing the “Dictator’s Aesthetic” is the first step in demanding a city that is built for human beings, not for the vanity of the corrupt.

Focus on Language

Let’s dive right into the language we used in the article because, honestly, talking about corruption and architecture gives us access to some incredibly rich and precise vocabulary that is useful way beyond just discussing politics. I want to walk you through about ten or so key phrases we used, break down what they really mean, and look at how you can drop them into your daily conversations to sound more articulate and precise.

First up, let’s talk about the word “Ostensibly.” We used this when talking about white elephants, saying they are “ostensibly symbols of progress.” This is such a power word. It means “apparently” or “supposedly,” but it carries a heavy hint that the reality is different. If you say, “I’m going to the library to study,” that’s a statement of fact. If you say, “I’m ostensibly going to the library,” you’re winking at me, implying you might actually be going to meet a date or take a nap. It’s a great way to introduce skepticism without being aggressive. You might say about a coworker, “He is ostensibly the project manager, but Sarah does all the work.”

Then we have the word “Facade.” In architecture, this literally means the face or front of a building. But metaphorically, and how we often use it in deep conversation, it refers to a deceptive outward appearance. We talked about looking past the “shiny facades.” In real life, you use this when someone is fake. “He keeps up a facade of being wealthy, but I know he’s drowning in debt.” It’s about the gap between what is shown and what is real.

Let’s move to “Illicit.” We talked about “illicit global capital.” This is a fancy, sharper way of saying “illegal” or “forbidden,” but it usually implies something shadowy or morally wrong, not just a parking violation. You hear it a lot with “illicit affairs” or “illicit trade.” If you want to describe something that feels sneaky and against the rules, this is your word. “They were found with illicit substances” sounds much more serious than just saying they had something they shouldn’t.

A really fun one is “Skim.” We mentioned it is easier to “skim money.” Originally, this comes from skimming the cream off the top of milk. In the context of corruption, it means taking a small amount of money from a large sum in a way that you hope isn’t noticed. But you can use this in non-criminal contexts too! You might “skim” a book, meaning you just read the top level or the basics without going deep. Or if you’re budgeting, you might say, “I can skim a little off the grocery budget to pay for the tickets.”

We also used the phrase “Manifestation.” We called buildings a “physical manifestation of laundered money.” This is a beautiful word. It means the physical or visible expression of an abstract idea. If you are stressed, and suddenly you get a rash, that rash is a physical manifestation of your stress. It’s when a thought or feeling becomes a real, touchable thing. You can use this to sound very philosophical. “His kindness is a manifestation of his good upbringing.”

Here is a phrase I love: “The Public Purse.” It sounds so much more elegant than “taxes” or “government money.” It refers to the collective wealth of the government that is supposed to be used for the people. When you are arguing about city spending, saying “This is a drain on the public purse” makes you sound like a serious commentator on civic affairs.

Let’s look at “Sterility” or “Sterile.” We talked about the “sterility of order.” In a hospital, sterile is good—it means no germs. But in art, architecture, or personality, sterile is an insult. It means lacking life, creativity, or warmth. If you walk into a house that is too white, too perfect, and has no personal photos, you might say, “It feels a bit sterile.” It implies it’s clean but dead.

Then there is “Insidious.” We described the pencil towers as “insidious.” This describes something that proceeds in a gradual, subtle way, but with harmful effects. It’s a creeping danger. A disease can be insidious; a bad habit can be insidious. It’s not a sudden explosion; it’s a slow rot. “The insidious influence of social media on his attention span was hard to notice at first.”

We used the term “Monolithic.” Literally, a monolith is a single large stone. We used it to describe massive buildings. But figuratively, we use it to describe an organization or system that is huge, powerful, and uniform—difficult to change. ” The government bureaucracy is monolithic.” It implies it’s big, slow, and unmovable.

Finally, let’s touch on “Veneer.” This is similar to facade. A veneer is a thin decorative covering of fine wood applied to coarser wood. We use it to describe a pleasant appearance that covers something bad. “A thin veneer of politeness covered his anger.” It suggests that if you scratch the surface just a tiny bit, the ugly truth is right there.

Now, I want to pivot to a little speaking lesson here because knowing these words is one thing, but using them with the right intonation is another. When we talk about corruption or critique society, our tone often needs to shift to be more “declarative” and “downward.”

When you ask a question, your voice goes up at the end? But when you make a critical point, you want your voice to go down at the end of the sentence. This signals authority. Try saying this sentence: “The building is just a facade.” If you go up at the end, you sound unsure. If you drop your pitch on “facade,” you sound like you know exactly what you are talking about.

So, here is your challenge for the week. I want you to look at a building in your town—maybe a new mall, a government building, or even a weirdly expensive house. Describe it to a friend or even just to yourself in the mirror. But I want you to be critical. Use three of the words we discussed. Maybe say, “This mall is ostensibly for the community, but it feels sterile, and I think it’s just a manifestation of corporate greed.” See how that feels? It changes how you think, not just how you speak.

Critical Analysis: Playing Devil’s Advocate

Alright, we have spent a lot of time nodding along to the idea that big, empty buildings are bad and that “Starchitecure” is essentially the devil in concrete form. And look, the arguments in the main article are solid. But if we want to be rigorous thinkers—and I know you do—we have to stop and poke holes in our own logic. We have to play the devil’s advocate. Because if we just accept the “Corruption Aesthetic” theory as a universal truth, we risk becoming just as blind as the people building these things.

Let’s start with the “White Elephant” concept. The article argues that massive projects like stadiums and museums are largely tools for graft. And yes, the math on corruption supports that. But is every underused mega-project a crime scene? Not necessarily. Sometimes, they are just… bets. Big, risky bets on the future.

Consider the “Bilbao Effect.” When Frank Gehry designed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, critics could have easily called it a vanity project. It was expensive, weird, and in a declining industrial city. But it worked. It revitalized the entire region’s economy through tourism. If we label every ambitious, expensive, or oversized project as “corruption,” do we risk killing ambition? Do we risk stopping the next Sydney Opera House or Eiffel Tower (which, remember, was hated when it was built) because we are too cynical to believe in the value of monumental architecture? Sometimes a nation builds big not to steal, but to inspire. We have to be careful not to confuse optimism with theft, even if the line is sometimes blurry.

Now, let’s look at the “Architecture of Intimidation.” The article claims that wide boulevards and massive squares are designed to make us feel small and powerless. That is a very specific, somewhat Western-centric psychological reading. In many cultures, scale is not about suppression; it is about collective pride.

A vast square might feel oppressive to someone used to the winding, medieval streets of Europe. But to someone else, that vastness might represent the capability and strength of their community. It provides space for mass celebration, for festivals, for a shared sense of “us.” Is Haussmann’s Paris—with its wide boulevards designed to move armies—evil? Or is it one of the most beloved cities on earth? The intent might have been control, but the result was beauty and utility. We have to separate the architect’s (or dictator’s) intent from the lived experience of the citizen. People are resilient. They take “intimidating” spaces and turn them into dance floors, skate parks, and picnic spots. We shouldn’t rob the citizens of their agency by assuming they are perpetually cowed by a big slab of concrete.

And finally, the fiercest critique: the “Pencil Towers” as safe deposit boxes. The article paints these as purely parasitic. But let’s look at the economics from a colder, perhaps more pragmatic angle. If a Russian oligarch buys a $50 million penthouse in New York and never lives there, that is $50 million of foreign capital entering the local economy (assuming the transaction isn’t totally black market). That owner pays property taxes—often millions a year—which go into the city’s budget to pay for schools, subways, and sanitation.

In a strange, twisted way, these absent billionaires are subsidizing the city. They consume zero services. They don’t crowd the subway, they don’t send kids to local schools, and they don’t call the police. They just pay taxes and leave. From a purely municipal budgeting standpoint, an empty luxury tower is a cash cow. Furthermore, is it possible that building super-luxury housing actually helps the housing crisis? There is a theory called “filtering.” If you don’t build high-end units for the rich, the rich will just buy the middle-class units and renovate them, pushing the middle class down, who then push the working class out. By building these “safe deposit boxes,” are we essentially creating a containment zone for global capital so it doesn’t eat up the rest of the housing stock?

I am not saying these counter-arguments are definitively right. But they complicate the narrative. It’s too easy to look at a glass tower and see only evil. The reality of urban economics, cultural aesthetics, and national ambition is a messy, gray area. And that is usually where the truth lives—not in the black and white, but in the gray.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to get you thinking and debating. When you head to the comments or talk to your friends, use these as a starting point to dig deeper.

Can “Dictator Architecture” ever be redeemed by the people?

Think about places that were built by terrible regimes but are now loved by the public. Can the meaning of a building change over time, or is it forever tainted by its creator? Does using a square for a protest “cleanse” it of its original purpose of control?

Is there a difference between a “Vanity Project” and a “National Landmark”?

Where is the line? The Eiffel Tower was considered a monstrosity. The Pyramids were built by slave labor (arguably) for the ego of one man. Yet we treasure them. At what point does a “White Elephant” become a heritage site? Is it just a matter of time?

Should architects be held morally responsible for who they build for?

If a famous “Starchitecht” designs a library for a dictator, are they complicit in the regime? Or are they just doing their job? Is architecture neutral, like a hammer, or is it political? Should there be an ethical code for where you accept commissions?

Do “Pencil Towers” and empty luxury real estate actually harm the average renter?

As mentioned in the critical analysis, does high-end construction absorb wealthy demand, or does it raise land values for everyone nearby, causing gentrification? If we banned foreign ownership of apartments, would rent actually go down, or would the economy just suffer?

Is the “clean and orderly” city actually desirable, or is it a trap?

We often complain about dirt and chaos in cities. But when a city becomes too clean and ordered (like the authoritarian ideal), does it lose its soul? How much “mess” is necessary for a city to feel free and alive?

Let me know what you think in the comments or just use these questions as talking points for your next conversation with your friends, if you still have those in our doom-scrolling age.

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Baron

Danny: Welcome back to the show. We’ve been talking about how corruption and authoritarianism shape our skylines. We’ve discussed the “why”—the greed, the ego, the control. But to really understand the “how,” I wanted to talk to the man who literally wrote the book on tearing down a city to stroke an Emperor’s ego. He’s the man who turned Paris from a medieval slum into the City of Light, allegedly stealing half the treasury in the process. Please welcome the Prefect of the Seine, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Baron, thank you for resurrecting yourself for this.

Haussmann: It is a pleasure, Danny. Although, looking at the architecture of this studio… dropped ceilings? Fluorescent lights? It seems my services are needed more than ever. It is dreadfully ugly in here.

Danny: I’ll take that as a compliment coming from the man who demolished twelve thousand buildings in Paris. You know, history often calls you a vandal. Do you accept that title?

Haussmann: A vandal destroys out of ignorance. I destroyed out of necessity. I was not a vandal; I was a surgeon. And yes, surgery is bloody, and surgery involves cutting out the rot. But when the patient wakes up, they can breathe. Paris was dying, Danny. It was a sewer. It was dark, it smelled of cholera and revolution. I gave it light. If that makes me a vandal, then hand me the sledgehammer.

Danny: You call it surgery; the people who lived there called it eviction. You displaced hundreds of thousands of poor Parisians. You pushed them out to the suburbs to build luxury apartments for the bourgeoisie. That sounds familiar to what we see today in places like London or New York. Was gentrification your invention?

Haussmann: “Gentrification” is such a clumsy, modern word. I prefer “Civilization.” You see, Danny, a capital city is not a charity ward. It is the face of the Empire. It is the living room of the nation. You do not hang your drying laundry in the living room when guests are coming. We needed a city that projected power, wealth, and stability. Did the poor have to move? Yes. But did I not also build them the aqueducts? Did I not build the sewers? Before me, the poor drank water that tasted of their neighbor’s waste. After me, they had clean water. I think that is a fair trade for moving a few kilometers to the outskirts.

Danny: A fair trade? You priced them out of their own history. But let’s talk about those wide avenues. You mentioned “projecting power.” The common historical theory is that you didn’t widen the streets for “light and air.” You widened them so you could march armies through the center of the city. You wanted to make it impossible for rebels to build barricades. You literally designed the city to be bulletproof against its own citizens.

Haussmann: Ah, the “strategic beautification” argument. I love this one. It gives me so much credit for military genius. Look, was it a happy accident that a thirty-meter-wide boulevard is harder to block with an overturned cart than a three-meter alley? Of course. Did the Emperor appreciate that the cavalry could charge from the barracks to the city center in fifteen minutes? I am sure he did. But to say that was the only reason is to be small-minded.

Danny: It’s not small-minded; it’s the definition of the “Architecture of Intimidation” we talked about in the article. You used geometry to crush dissent.

Haussmann: I used geometry to crush chaos, Danny! There is a difference. Democracy loves chaos. It loves crooked streets and jagged skylines because it loves the individual. “Oh, look at me, I want my house to look different from my neighbor’s!” It is selfish. The Empire is about the collective. The Boulevard serves the collective. It allows the circulation of air, of traffic, of money. If it also allows the circulation of troops to maintain order, well, order is a prerequisite for beauty. You cannot admire a statue if you are being hit in the head with a cobblestone by a revolutionary.

Danny: So you admit it. The aesthetics were a tool for control.

Haussmann: All architecture is control, Danny. When you build a wall, you control who enters. When you build a door, you control who leaves. The only difference is that I was honest about it. I wanted Paris to behave. And look at the result! You tourists flock there today. You take selfies on my boulevards. You pay six dollars for a coffee just to sit on the sidewalks I designed. You love the control. You love the uniformity. You love that every building is the same height, the same stone, the same balcony. You say you love “freedom,” but you spend your vacations in the most strictly regulated urban environment on earth. The irony is delicious.

Danny: That’s… actually a fair point. We do love the uniformity of Paris. But let’s talk about how you paid for it. In the article, we talk about the “White Elephant” phenomenon—how corruption thrives in massive projects. You were famous for your “Fantastic Accounts.” You borrowed money to pay the interest on the money you borrowed before. It was a Ponzi scheme with nice balconies.

Haussmann: “Ponzi scheme” is so vulgar. It was “Creative Finance.” Listen, Danny, you cannot build a new world with the pocket change of the old world. I spent… let’s say, 2.5 billion francs. A staggering sum. The Parliament screamed. The critics howled. They said I was bankrupting France. But look at the return on investment! I increased the value of Paris real estate by a thousand percent. I created a tax base that sustained the French Republic for a century.

Danny: But you skimmed a little, didn’t you? There were rumors about land speculation. You’d decide where a new boulevard was going, and suddenly your friends would buy the land there a week before the announcement. That’s the oldest trick in the corrupt politician’s handbook.

Haussmann: I was a public servant! I died with debts, I assure you. Did my friends get rich? Perhaps. But in order to move a mountain, you need greased wheels. If a few bankers made a fortune, so be it. They provided the capital to build the Opera House. You focus on the pennies lost to “corruption”; I focus on the monument gained for eternity. This is the problem with you modern moralists. You would rather have a perfectly audited, budget-neutral sewer than a Palace of Versailles. You worship the spreadsheet; I worship the skyline.

Danny: I worship not going to jail for fraud, but okay. Let’s pivot to the modern day. I want your take on what we see now. The “Pencil Towers” in New York. The empty stadiums in Qatar. The ghost cities in China. Do you see yourself in them?

Haussmann: I see the ambition, but I do not see the taste. That is the tragedy.

Danny: Explain that.

Haussmann: Take those “Pencil Towers” you mentioned. I have seen pictures. They are needles. They are selfish. Each one screams, “Look how tall I am!” They do not care about the street. They do not care about the building next door. They are solitary spikes of ego. My Paris was a chorus; everyone sang the same note to create a harmony. These modern oligarch towers… they are just a shouting match.

Danny: So you dislike them?

Haussmann: I despise them. Not because they are for the rich—I like the rich, they have better dinner parties—but because they are anti-social. A city must have a fabric. These towers tear the fabric. And the ghost cities? Please. I built Paris to be lived in, to be trampled upon, to be used. Building a city just to balance a ledger in Beijing… that is not architecture. That is masturbation.

Danny: Wow. Okay. But isn’t that exactly what you did? You built monuments to the Emperor.

Haussmann: I built monuments to France! And I built them to last. These modern glass things… they will fall apart in fifty years. The sealant will crack, the glass will fog. My stone gets more beautiful with age. That is the difference between an Oligarch and an Emperor. An Oligarch thinks about the next quarter’s profit. An Emperor thinks about the next century. You have replaced tyranny with capitalism, and you lost the sense of eternity.

Danny: You’re arguing that a Dictator’s Aesthetic is better because it has a long-term vision?

Haussmann: Precisely. Look at your democracies. You cannot build a high-speed train line because three farmers and a badger are protesting the route. It takes you twenty years to build a runway. In my day, I drew a line on a map, and the demolition crews arrived the next morning. Was it brutal? Yes. Was it effective? undeniably. You cannot have great cities without a little bit of tyranny. You want the omelet, Danny, but you are crying over the eggshells.

Danny: But those eggshells were people’s lives!

Haussmann: And now those people are dust, and the city remains. History is ruthless. It remembers the stone, not the sweat. Do you think the people who hauled the rocks for the Pyramids were having a good time? No. But we admire the Pyramids. We do not admire the “fair labor practices” of the 24th Century BC. You interview me because I am a “Great Man” of history. But if I had been a nice man, a gentle man, a man who listened to every complaint… you would not know my name, and Paris would still be a medieval toilet.

Danny: That’s a bleak view of humanity. That beauty requires suffering.

Haussmann: It is the only view supported by five thousand years of evidence. Beauty is expensive. It costs money, it costs labor, and yes, it often costs freedom. You want your cities to be “fair.” I wanted my city to be “grand.” We simply have different priorities.

Danny: Let’s talk about the “White Elephants” again—the useless projects. You built the Paris Opera. It was arguably a vanity project.

Haussmann: It is the most beautiful building in the world!

Danny: It was wildly over budget. It was excessive. It was gold-plated everything. Why? Why does power always need gold leaf?

Haussmann: Because power is an illusion, Danny. The Emperor is just a man. The State is just a piece of paper. To make people believe in the State, to make them obey the laws and pay their taxes, you must dazzle them. You must create a stage set where the State looks invincible. The gold leaf, the marble, the high ceilings… it is theater. If the Emperor lived in a shack, nobody would bow. We built the Opera not just for music, but to show the world that France was rich, cultured, and powerful. It was propaganda. And it worked.

Danny: So, the Dictator’s Aesthetic is basically just specialized marketing.

Haussmann: Everything is marketing. The Catholic Church knew this—that’s why they built cathedrals. The Soviets knew this—that’s why they built those massive statues. And your modern developers know this—that’s why they build “amenity decks” and “infinity pools” that nobody uses. The difference is, my marketing created a stage for human life. Their marketing creates a stage for loneliness.

Danny: I want to go back to something you said earlier. You said we replaced tyranny with capitalism. In the article, we argue they are merging. That the oligarchs are the new tyrants, just without the flags.

Haussmann: A fascinating point. But the Oligarch has no responsibility. The Emperor, for all his faults, considers the country his property. He wants to take care of his property. If the people starve, the Emperor looks bad. The Global Capitalist? He does not care if New York sinks into the ocean, because he has a house in London and another in New Zealand. He has no loyalty to the soil. That is why their architecture feels so hollow. It is nomadic money. It lands, it builds a glass box, it extracts value, and it flies away. I was rooted in the mud of the Seine. I loved Paris. Does the developer of that pencil tower love 57th Street? I doubt he can even find it on a map without his driver.

Danny: So, weirdly, you are arguing for more authoritarianism, but of a local variety?

Haussmann: I am arguing for ownership. Corruption is inevitable, Danny. Humans are greedy. If you are going to be robbed, wouldn’t you rather be robbed by a man who at least builds you a nice park in return? The modern system robs you and gives you nothing but a shadow over your backyard. I was a pirate, perhaps. But I shared the booty with the city. These modern men are just leeches.

Danny: You have a very seductive way of justifying terrible things, Baron.

Haussmann: That is why I was the Prefect.

Danny: Let’s imagine you are hired today. You are the “Prefect of Los Angeles” or the “Prefect of London.” What do you do?

Haussmann: Los Angeles… God, what a mess. I would need a lot of gunpowder.

Danny: Okay, assuming you have the gunpowder.

Haussmann: I would tear out the highways. They are the new city walls, cutting neighborhoods in half. I would build a grand axis—a spine. A city needs a spine. Right now, Los Angeles is just a pile of limbs flailing around. I would impose a uniform height limit. No more of these random towers. Everything must be six stories high. Dense, bustling, human scale. And I would bankrupt the city doing it, of course. But in a hundred years, they would build a statue of me.

Danny: And the people who lose their homes?

Haussmann: They will complain on your “Twitter.” And then, ten years later, their children will sit in the new cafes and say, “Wow, isn’t this neighborhood charming?” Amnesia is the architect’s best friend.

Danny: You really don’t care about the individual suffering, do you?

Haussmann: I care about the species. The individual is temporary. The city is permanent. If you want to make an omelet…

Danny: Yeah, yeah, the eggs.

Haussmann: The eggs must be broken.

Danny: Before we wrap up, I have to ask about the “Sterility” aspect. We criticized modern corrupt cities for being sterile. Too clean. No grit. You “cleaned” Paris. Did you worry about making it boring?

Haussmann: Boring? Paris? Jamais. But I understand the fear. When you impose order, you risk killing the spirit. But here is the secret: You build the stage, but you let the actors write the play. I built the boulevards, but I did not tell the people what to drink, what to wear, or who to kiss. The modern “safe deposit box” cities… they try to control the actors too. They have private security guards, rules against loitering, rules against noise. That is death. I built public spaces. Truly public. The Boulevard belongs to the dandy, the prostitute, the banker, and the beggar. As long as they keep moving.

Danny: “As long as they keep moving.” That’s the catch.

Haussmann: Circulation, Danny. Life is movement. Stagnation is death. The old Paris was stagnant. My Paris flows.

Danny: One final question. If you could say one thing to the modern architects—the ones building these generic glass towers for money launderers—what would it be?

Haussmann: I would tell them: “Gentlemen, you are building tombstones. You are building glass coffins for dead money. Try, just for once, to build a cathedral for the living. It costs more, but at least you won’t be forgotten before the concrete is dry.”

Danny: Baron Haussmann, you are a charming monster. Thank you for joining us.

Haussmann: The pleasure was mine. Now, can someone direct me to the nearest wide avenue? I feel claustrophobic.

Danny: I think we have a fire exit out back that leads to an alley.

Haussmann: An alley? How barbaric. Au revoir, Danny.

Danny: Au revoir, Baron. And there you have it, folks. The man who invented the Dictator’s Aesthetic. He makes a compelling case: if you’re going to sell your soul to corruption, make sure you get a beautiful city in the trade. But looking at the empty glass towers of today… I’m not sure we’re getting the same deal.

0 Comments