- The Art of the Lie: Deception as a Survival Strategy

- Chimpanzee Politics: The Origins of the Bribe

- The Dunbar Number: Why We Can’t Handle “Fairness”

- The Selfish Gene vs. The Social Contract

- The Animal in the Office

- Focus on Language

- Critical Analysis: The Naturalistic Fallacy Trap

- Let’s Discuss

- Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Prince of Realism

- Let’s Play & Learn

- Check Your Understanding (Quiz)

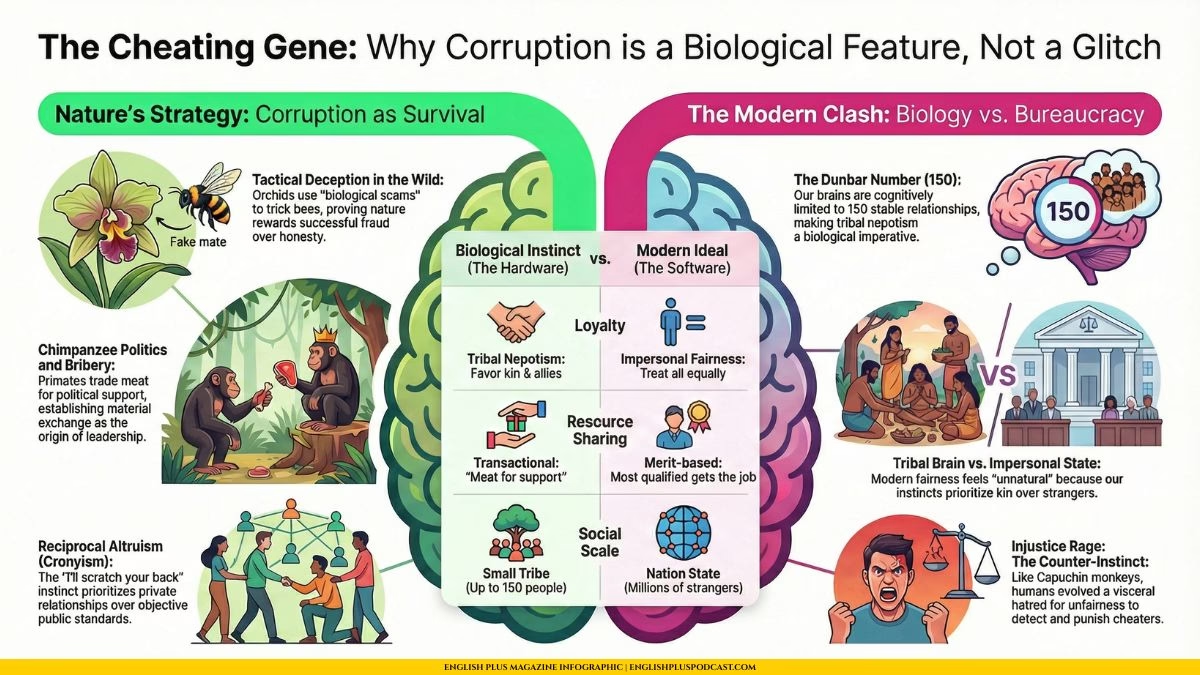

We tend to speak of corruption with a specific kind of moral revulsion. We call it a cancer, a rot, a stain on the fabric of society. We describe it as something fundamentally “inhumane,” as if the act of taking a bribe or favoring a cousin over a qualified stranger is a deviation from our noble human nature. We like to believe that fairness is the factory setting for our species and that corruption is a glitch introduced by greed, bad parenting, or capitalism.

But what if we have it backward? What if corruption isn’t a glitch, but a feature?

If you spend enough time looking at the behavior of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, or even at the deceptive beauty of a flower in the rainforest, you start to see a very different picture. Biology suggests that the instinct to cheat, to bribe, and to play favorites might be one of the most natural things we do. It raises an uncomfortable question that moral philosophers and urban planners hate to ask: If a chimpanzee trades a slab of stolen meat for political support from a rival, is that a bribe? And if it is, does that mean corruption is written into our DNA?

The Art of the Lie: Deception as a Survival Strategy

Let’s start with the basics. In the human world, we prize honesty. We teach our children that the truth will set them free. But in the wild, the truth will usually get you eaten. Nature does not reward honesty; nature rewards successful deception.

Evolution is, in many ways, an arms race between the liar and the lie-detector. Consider the orchid. We think of flowers as passive, beautiful decorations, but some orchids are actually con artists of the highest order. Take the Ophrys genus of orchids. They don’t produce nectar to attract bees like honest, hardworking flowers. Instead, they have evolved to look and smell exactly like a female bee. When a male bee comes along, looking for a mate, he sees the orchid, lands on it, and attempts to mate with it. He gets nothing but frustration, but the orchid gets exactly what it wanted: pollination. The bee flies off, dusted with pollen, to be tricked by the next flower.

This is fraud. It is a biological scam. The orchid promises a reward (mating) that it has no intention of delivering, in exchange for a service (pollination). If this happened in the business world, the orchid would be sued for breach of contract. In nature, the orchid is an evolutionary success story.

The Cuttlefish Cross-Dresser

The ocean is just as full of liars. Look at the giant cuttlefish. In this species, the large, aggressive males guard the females, fighting off any rivals who try to approach. Small males don’t stand a chance in a fair fight. So, they cheat.

The small male cuttlefish can change his skin color and texture. He pulls in his tentacles to mimic the shape of a female. He then swims right past the aggressive guard male, pretending to be a lady cuttlefish. The big male thinks, “Ah, another female for my harem,” and lets him pass. Once inside the circle of trust, the small male drops the disguise, mates with the female right under the big guy’s nose, and swims away.

This is “tactical deception.” It is the biological equivalent of using a fake ID or sneaking into a VIP club. It suggests that “playing by the rules” is a strategy for the strong, while “cheating” is often the only strategy available to the underdog. When we look at human corruption, we often see it as a tool of the powerful, but biology reminds us that deception is often a survival mechanism for those who cannot win a fair fight.

Chimpanzee Politics: The Origins of the Bribe

Orchids and cuttlefish are one thing, but they don’t have complex societies. To really understand the roots of political corruption—bribery, nepotism, cronyism—we have to look at our cousins: the primates.

The Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal famously coined the term “Chimpanzee Politics,” and for good reason. A chimp troop is not a democracy, but it isn’t a simple tyranny of the strongest, either. You might assume the Alpha Male is just the biggest, scariest chimp who beats everyone else up. Sometimes that is true. But usually, the brute doesn’t last long. To stay on top, you need coalitions. You need friends.

And how do you get friends in the jungle? You buy them.

Meat for Support

In chimp societies, meat is a luxury item. When a hunting party catches a colobus monkey, the carcass is highly valuable. The owner of the meat has a choice. He can eat it all himself, or he can share. Studies have shown that Alpha males—or males who want to become Alpha—are incredibly strategic about who gets a bite.

They don’t share with the hungry; they share with the useful. A male will give a choice piece of meat to an older, influential male whose support he needs to overthrow the current leader. He will share with his key allies to ensure their loyalty in the next fight. This is, by definition, a transaction: material goods (meat) exchanged for political influence (support).

In a human court of law, we call this “vote-buying.” We put politicians in jail for handing out cash or turkeys in exchange for votes. But for chimps, it is simply good leadership. It is the glue that holds the coalition together. This suggests that the impulse to use resources to secure loyalty is not a “corruption” of leadership; it is the origin of leadership.

The Grooming Economy

It isn’t just food. Primates operate on a massive economy of “grooming.” Grooming is pleasurable, it cleans the fur, and it lowers stress. But it is also a currency. “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” is not just a metaphor; it is the literal constitution of primate society.

If a chimp gets into a fight, who jumps in to help him? Usually, it’s the guy he groomed yesterday. This is “Reciprocal Altruism.” Ideally, it sounds nice. It sounds like friendship. But looking closer, it is also the basis of cronyism. It is a system where you help those who have paid you, not those who are right. If your grooming partner starts a fight he is clearly wrong to start, you jump in anyway. You don’t care about “justice”; you care about your investment.

This is where the seeds of corruption lie. Corruption is essentially the prioritization of a private relationship over a public standard. It is helping your friend get the construction contract even though his bid is higher, because he “groomed” you (bought you dinner, hired your son, donated to your campaign). Our primate brain sees this as loyalty. The modern state sees it as a crime.

The Dunbar Number: Why We Can’t Handle “Fairness”

So, we have a brain that is wired for deception (like the orchid) and wired for transactional loyalty (like the chimp). But there is a third biological factor that makes modern corruption almost inevitable: The Dunbar Number.

Evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar theorized that there is a cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships. That number is roughly 150. For most of human history, we lived in tribes of about that size. In a tribe of 150, everyone knows everyone. If you catch a fish, you share it with your cousin, because you know he will help you fix your hut next week.

In this tribal context, “nepotism”—favoring your family—is a survival imperative. If you are the chief and you give the best food to a stranger instead of your own children, you are an evolutionary failure. Your genes will die out. In the tribe, treating everyone “equally” is madness. You should favor your kin and your allies.

The Clash with the Modern State

The problem arises when we take this Stone Age brain, designed for a village of 150, and drop it into a nation-state of 300 million.

Modern democracy and bureaucracy are built on the idea of “Impersonal Fairness.” A judge is supposed to treat the defendant exactly the same whether they are strangers or brothers. A hiring manager is supposed to give the job to the most qualified candidate, not the one they like the most.

This goes against every instinct in our body. Our biology screams at us to help our friends. When a politician gives a job to his unqualified nephew, his “modern” brain might know it’s illegal, but his “tribal” brain feels good about it. He is taking care of his own. He is being a good tribal member.

Corruption, in this view, is simply the friction between our small-scale biology and our large-scale civilization. We are trying to run software designed for a family picnic on hardware designed for an empire. The “impersonal” nature of the state feels cold and unnatural to us. We crave the personal connection. We want to know “a guy” at the DMV. We want the police officer to let us off with a warning because he knows our dad. We want the comfort of the bribe because the bribe re-personalizes the interaction. It turns a faceless bureaucrat back into a trading partner.

The Selfish Gene vs. The Social Contract

Does this mean we are doomed? If corruption is natural, should we just accept it?

Not necessarily. Biology is not destiny. We are also the only species that has invented things like “Laws,” “Ethics,” and “The Future.”

While the “Selfish Gene” encourages us to cheat to get ahead, humans have also evolved a powerful counter-instinct: the ability to detect and punish cheaters. We have a deep, visceral hatred of unfairness. You can see this in experiments with Capuchin monkeys. If you give two monkeys a cucumber, they are happy. But if you give one monkey a grape (which they love) and the other a cucumber for the same task, the cucumber monkey will freak out. He will throw the cucumber at the researcher. He will shake the cage. He perceives the inequity and he rejects it.

This “injustice rage” is the biological root of the anti-corruption movement. We are torn between two biological drives: the drive to cheat for our own advantage, and the drive to punish others who cheat. Civilization is essentially our attempt to institutionalize the second drive to control the first.

Overcoming the Factory Settings

We have to recognize that creating a corruption-free society is an act of rebellion against nature. It requires constant vigilance because gravity is always pulling us back toward cronyism. When we build strong institutions, independent courts, and transparent banking systems, we are building scaffolds to support a morality that our biology can’t sustain on its own.

We are not naturally good. We are naturally collaborative, yes, but that collaboration is usually limited to our “Us.” Expanding that circle of “Us” to include the whole country, or the whole world, is a massive cognitive leap. It is a triumph of software over hardware.

The Animal in the Office

So, is corruption natural? Yes. It is as natural as the orchid lying to the bee or the chimp bribing his way to the top. The urge to use resources to buy loyalty, to favor our kin, and to bend the rules for our tribe is baked into our evolutionary history.

But “natural” does not mean “inevitable,” and it certainly doesn’t mean “good.” Smallpox is natural. Arsenic is natural. Dying at thirty is natural. The entire project of human civilization is about defying what is natural in favor of what is better.

Recognizing the biological roots of corruption shouldn’t make us cynical; it should make us realistic. It explains why corruption is so hard to stamp out—it keeps growing back because the roots are in our own psychology. It reminds us that the fight against oligarchy and graft isn’t just a political struggle; it’s a struggle against our own inner chimpanzee. We are fighting millions of years of programming that tells us to give the meat to our friends. And the only weapon we have is the fragile, uniquely human idea that strangers deserve justice too.

Focus on Language

Let’s dig into the language of the article. We used a lot of words that bridge the gap between biology, politics, and psychology. Understanding these terms gives you a toolkit for analyzing human behavior in a much more sophisticated way. Instead of just saying “he’s greedy,” you can explain why he’s acting that way using evolutionary concepts.

I want to look at ten key phrases we used, break them down, and show you how to use them in your daily life, whether you’re talking about politics or office drama.

First, let’s talk about “Reciprocal Altruism.” This is a fancy biological term for “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” In the article, we used it to describe chimps grooming each other. In real life, this is the basis of most networking. If you help a colleague with a report today, you expect them to cover for you next week. That’s reciprocal altruism. You can use this to sound very analytical. If someone asks why you are doing a favor for a difficult coworker, you can say, “I’m just banking some reciprocal altruism for later.”

Next is “Nepotism.” This comes from the Latin word for “nephew.” It specifically means people with power or influence favoring relatives or friends, especially by giving them jobs. We talked about how the “tribal brain” loves nepotism. In the workplace, this is a very common complaint. “The boss’s son got the promotion? That is blatant nepotism.” It’s a powerful accusation because it implies incompetence—the person didn’t earn the spot; they inherited it.

Then we have “Cronyism.” This is nepotism’s cousin. Instead of family, it’s about friends or associates (cronies). We mentioned chimps sharing meat with allies as a form of cronyism. If a politician gives a building contract to his golf buddy, that’s cronyism. You might say, ” The board of directors is full of cronyism; they all went to the same college.”

Let’s look at “Imperative.” We used the phrase “survival imperative.” An imperative is something of vital importance; a crucial command. If something is a biological imperative, you must do it to survive. In business or life, you use this to show urgency. “It is a moral imperative that we fix this safety issue.” It sounds much stronger than just saying “we should do it.”

We used the term “Cognitive Dissonance.” This is a psychological term describing the mental discomfort experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. We talked about the cognitive dissonance of protesting billionaires while watching Batman. In the context of corruption, a politician might feel cognitive dissonance if they think of themselves as honest but still take bribes. You can use this when someone is being hypocritical. “He says he loves animals but eats steak every day; that must cause some cognitive dissonance.”

A fun one is “Visceral.” We talked about a “visceral hatred of unfairness.” Visceral literally relates to the internal organs (viscera/guts). Figuratively, it means deep, inward feelings rather than the intellect. A visceral reaction is a “gut feeling.” It’s raw and emotional. “I had a visceral reaction to that horror movie.”

Let’s talk about “Impersonal.” We described the modern state as “impersonal.” Usually, we think of this as bad (cold, distant). But in justice, impersonal is good. It means not influenced by personal feelings. “The law must be impersonal to be fair.” You can use this to defend a tough decision. “Don’t take it personally; it was a purely impersonal business decision.”

We also used “Stratagem.” (Or strategy, but let’s upgrade to stratagem). A stratagem is a plan or scheme, especially one used to outwit an opponent or achieve an end. The orchid’s mimicry is a biological stratagem. It implies a trick. “His sudden apology was just a stratagem to avoid punishment.”

Then there is “Glitch.” We asked if corruption is a “glitch.” A glitch is a sudden, usually temporary malfunction or irregularity of equipment. In conversation, we use it to mean a small error. “Sorry I’m late, there was a glitch in my alarm clock.” Using it metaphorically (“a glitch in human nature”) suggests it wasn’t intended to be there.

Finally, “Scaffold.” We said institutions are “scaffolds” for morality. A scaffold is a temporary structure used to support a work crew and materials to aid in the construction. Metaphorically, it’s anything that supports something else while it’s being built or maintained. “I use these notes as a scaffold for my presentation.”

Speaking Section: The Art of Justification

Now, let’s move to speaking. When we talk about corruption or “cheating,” the most common speaking skill involved is Justification.

Humans are masters of justifying their actions. We rarely say, “I did it because I’m bad.” We say, “I did it because…” and then we frame it as necessary or natural.

I want to teach you a technique called “Reframing.” This is where you take a negative action and describe it using positive or neutral vocabulary. This is what politicians (and chimps, if they could talk) do.

- Negative: “I bribed him.”

- Reframed: “I facilitated the transaction.”

- Reframed: “I showed my appreciation for his help.”

- Negative: “It was nepotism.”

- Reframed: “I hired someone I trust.”

- Reframed: “I wanted to ensure team chemistry.”

The Challenge:

I want you to think of a time you broke a small rule. Maybe you jaywalked, maybe you skipped a line, or maybe you told a white lie.

I want you to speak out loud and Justify it using the vocabulary we learned. Try to make it sound like a biological imperative or a social necessity.

Example: “Yes, I ate the last cookie. But it wasn’t greed. It was a survival imperative. Also, I shared my lunch yesterday, so this is really just reciprocal altruism.”

See how that works? It makes you sound smart, even when you’re being naughty. Try it out!

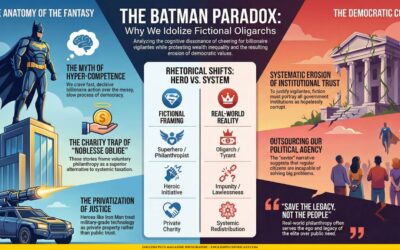

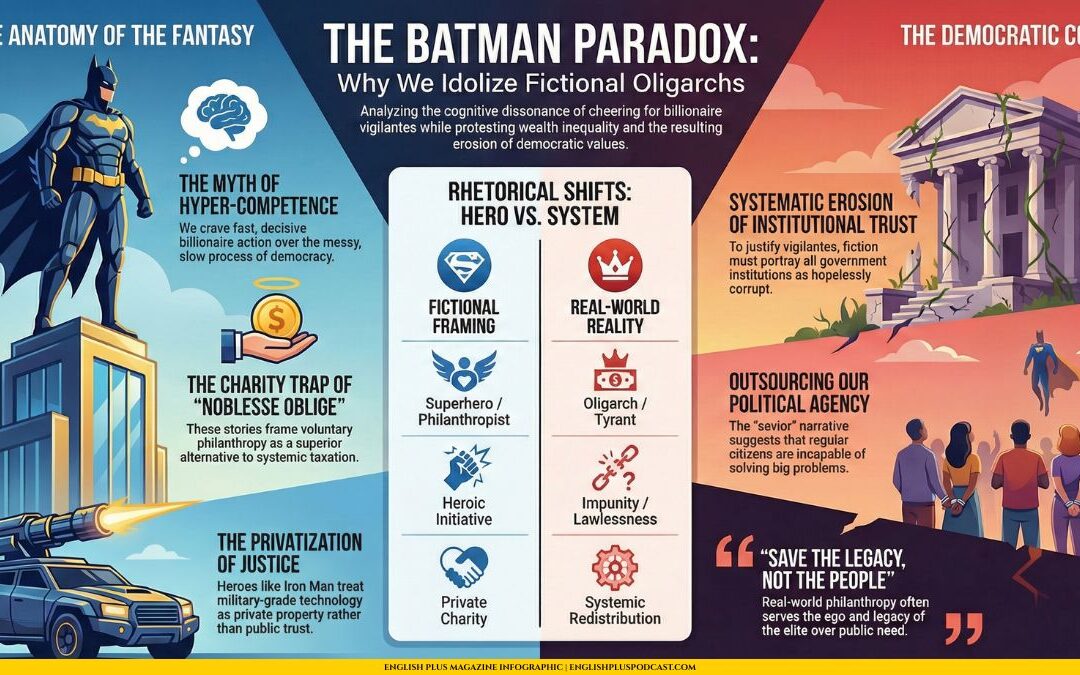

Critical Analysis: The Naturalistic Fallacy Trap

We have spent quite some time building a very convincing case that corruption is natural, biological, and perhaps inevitable. The arguments are seductive. The orchids do it! The chimps do it! It’s in our Dunbar number!

But as critical thinkers, we need to slam on the brakes. There is a massive logical trap hidden in this entire line of reasoning, and if we fall into it, we risk justifying some truly terrible things.

It is called the Naturalistic Fallacy.

The Naturalistic Fallacy is the error of assuming that because something is natural (it exists in nature), it is therefore good or morally right. This is a dangerous leap of logic.

Let’s play Devil’s Advocate against our own article.

1. Nature is a Horror Show

If we use “nature” as our moral compass, we are in big trouble. In nature, infanticide is common. Male lions kill the babies of rival males. Is that “good”? Rape is common in many species (ducks are notorious for it). Is that “good”? Slavery exists in nature (some ants enslave other ants). By the logic of “The Cheating Gene,” we could argue that murder, rape, and slavery are just “biological features” and therefore acceptable.

Obviously, we don’t accept that. We define our humanity in opposition to nature. We created laws specifically to stop strong people from killing weak people, which is the most natural thing in the world. So, why should we accept corruption just because chimps do it? The “it’s natural” argument falls apart the moment you apply it to almost any other crime.

2. The Complexity of Human Culture

The article focuses heavily on evolutionary psychology, which often treats humans as “chimps with pants.” This ignores the massive power of Culture. Humans are not just slaves to our genes. We are products of our software (culture) as much as our hardware (biology).

There are human societies that are incredibly non-corrupt (think of Denmark or New Zealand). There are others that are deeply corrupt. If corruption were purely genetic, every human society should have roughly the same level of corruption. But they don’t. The variance is huge. This proves that culture, institutions, and education can override biological impulses. We aren’t just chimps; we are chimps that can rewrite our own operating system.

3. The “Cronyism is Efficiency” Myth

The article hints that chimp bribery is “good leadership” because it creates stability. Some economists have argued this for humans too—that corruption is just “grease for the wheels” of a slow bureaucracy.

Let’s challenge that. Is it really grease? Or is it sand?

When you give a job to your nephew (nepotism), you are by definition NOT giving it to the most competent person. Over time, this leads to a collapse in competence. Bridges fall down because the engineer was the mayor’s cousin, not the best engineer. Economies stagnate because the best ideas don’t get funding, only the best-connected ideas do. “Chimp politics” works for a troop of 50 where the stakes are a dead monkey carcass. It does not work for a nuclear power plant or a national healthcare system. The “efficiency” of corruption is a short-term illusion that leads to long-term disaster.

4. The Dunbar Number isn’t a Prison

We talked about the Dunbar Number (150 people) as a limit we can’t escape. But is it? We have invented “Fictive Kinship.” This is the ability to treat strangers like family. When a soldier dies for his country, he is dying for millions of people he has never met. He has hacked his Dunbar Number. He has expanded his “tribe” to include a flag, an idea, or a religion.

If we can convince people to die for strangers (war), we can certainly convince them not to steal from strangers (anti-corruption). We are not trapped by our small-group brain; we transcend it all the time.

So, while the biological perspective is fascinating and explains the origin of the impulse, it offers zero justification for the practice. We are the only animal that can choose to be unnatural. And when it comes to corruption, being unnatural is the highest virtue we can aspire to.

Let’s Discuss

Here are five questions to get you thinking and debating. Take these to the comments section or discuss them with your friends.

If you were a judge and your brother was on trial for a minor crime, would you recuse yourself?

Most people say “yes” immediately. But what if you knew the other judge was harsh and unfair? Would your “tribal” duty to protect your brother outweigh your “civic” duty to the law? Where is the line?

Is “networking” just socially acceptable corruption?

We tell people to “build a network” to get jobs. This usually means using personal connections to bypass the standard application pile. How is this different from cronyism? Is it just a matter of degree?

Can a society ever be 100% free of corruption, or would that be inhuman?

Imagine a world where zero favors are ever done. A world of pure, cold bureaucracy where no one ever helps a friend. Would you want to live there? Is a little bit of corruption the price we pay for having human relationships?

Do you think women are less corrupt than men?

This is a controversial one! In chimp societies, the males play the heavy political games. Some studies suggest women score higher on agreeableness and rule-following. Others say power corrupts everyone equally. What does the “nature” argument suggest?

If an alien watched human politics, would they see a difference between “Lobbying” and “Bribery”?

In the US, corporations pay millions to “lobby” politicians. It’s legal. In other countries, they hand cash in envelopes. It’s illegal. Is the distinction merely legal, or is there a moral difference? Is lobbying just a sophisticated primate meat-exchange?

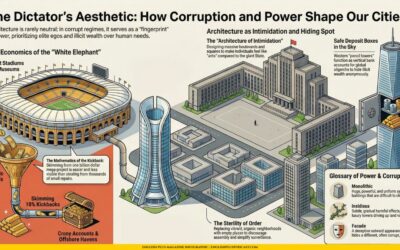

Fantastic Guest: Danny vs. The Prince of Realism

Danny: Welcome back to the show. We’ve been exploring the uncomfortable idea that corruption—bribery, nepotism, deception—might be hardwired into our DNA. We’ve looked at orchids that lie to bees and chimpanzees that buy votes with meat. It’s a biological argument for bad behavior. But to really understand the politics of this biology, I wanted to talk to the man who literally wrote the book on being ruthless. He is the author of The Prince, a man whose name is synonymous with scheming, and who would probably look at a lying orchid and say, “That flower has great potential.” Please welcome the Florentine diplomat himself, Niccolò Machiavelli. Niccolò, welcome to the 21st century.

Machiavelli: Thank you, Danny. It is a strange century. You have devices that let you speak to the entire world instantly, yet your leaders still make the same mistakes as the Borgias. It is comforting, in a way. Technology changes; human nature remains delightfully disappointing.

Danny: “Delightfully disappointing” might be the best description of humanity I’ve ever heard. Now, I brought you here because our article suggests that “cheating” is natural. We usually call you the father of political corruption—or at least the father of justifying it. When you hear that a chimpanzee trades meat for political support, does that sound familiar to you?

Machiavelli: Familiar? It sounds like Tuesday in Florence. You call it “corruption” or “cheating.” I call it necessità—necessity. The chimpanzee is not “cheating.” The chimpanzee is governing. If he keeps the meat to himself, the other chimpanzees will eventually tear him apart. By distributing the meat, he buys their loyalty. He buys his own survival. This is not a crime, Danny. This is the fundamental architecture of power. If your modern politicians stopped pretending they were saints and admitted they were simply chimpanzees with better tailors, your societies would be much more stable.

Danny: But that’s the thing, Niccolò. We want to be better than the chimps. We have laws. We have ethics. We have this idea of the “impersonal state” where everyone is treated equally. You seem to think that trying to be “fair” is actually a mistake.

Machiavelli: Fairness is a lovely concept for poets and priests. It is a disaster for princes. Look at your “impersonal state.” You say a leader should treat a stranger the same way he treats his ally. Biologically, as you laid out in your article, this is nonsense. Politically, it is suicide. If I treat my enemy with the same “fairness” as my friend, my friend has no reason to bleed for me. And my enemy has no reason to fear me. The “impersonal state” is cold. It offers no warmth. Men do not die for a bureaucracy, Danny. They die for a man who gave them meat when they were hungry. Or a man who groomed their fur when they were stressed.

Danny: So you’re saying cronyism—helping your friends—is actually the glue of society? That’s a hard sell in a democracy. We call that corruption.

Machiavelli: You call it corruption because you have the luxury of safety. In the jungle—or in 16th-century Italy—safety is a fleeting illusion. You need a tribe. Your “Dunbar Number” theory fascinates me. If the human brain can only truly care about 150 people, then a state of 300 million is a lie. It is a fiction. To manage such a fiction, you need Grease. You need the favor. You need the transaction. When a politician gives a contract to a donor, he is bridging the gap between the cold, abstract State and the warm, human reality of the Tribe. He is saying, “I see you. You are one of my 150.” Is it “fair” to the other 299 million? No. Is it natural? Absolutely.

Danny: But doesn’t that lead to incompetence? If I hire my cousin to build the bridge instead of the best engineer, the bridge falls down. That’s the flaw in your “Realpolitik.” The meat-for-support system creates a crumbling world.

Machiavelli: Ah, you mistake me for an advocate of stupidity. I never said a Prince should be incompetent. A Prince who hires an idiot cousin is not a Machiavellian; he is a fool who will soon lose his state. The smart corruption, Danny, is hiring the competent cousin. Or, better yet, hiring the competent stranger and making him your cousin through marriage or gold. You see, the bridge falling down is bad for the Prince too. If the bridge falls, the people hate him. A wise Prince uses corruption to secure loyalty, but he uses merit to secure results. The problem with your modern world isn’t that you have corruption; it’s that you have inefficient corruption. You have people stealing the meat and giving nothing back to the troop. That is not leadership; that is parasitism.

Danny: I love that distinction: “Inefficient Corruption.” It sounds like a corporate buzzword. Let’s talk about the orchids. The Deception. You famously said a Prince must be a “Fox” to recognize traps and a “Lion” to scare wolves. The orchid that mimics a female bee to trick the male… is that the ultimate Fox move?

Machiavelli: It is masterful. Truly art. The orchid understands the most important rule of existence: Mundus vult decipi—the world wants to be deceived. The male bee does not want the truth. The truth is that the orchid is a plant with no nectar. The truth is boring. The bee wants the fantasy of the female. The orchid provides the fantasy. In return, the orchid gets what it needs.

Danny: That sounds incredibly cynical. You’re saying voters—or citizens—are just hornier bees?

Machiavelli: I am saying that people judge by their eyes, not by their hands. Everyone sees what you appear to be; few experience what you really are. A leader who is always honest—who tells the people, “I cannot give you this meat because the budget is tight” or “I cannot protect you because the enemy is too strong”—that leader will be despised. The leader who lies—who says, “I am strong, I am rich, I will give you everything”—he attracts the pollination. He attracts the votes. Is it moral? No. Is it effective? Ask the orchid. It is still blooming, is it not?

Danny: So nature rewards the best liar. But we have developed these things called “Audit Committees” and “Journalists” to catch the liars. The orchid doesn’t have to deal with an investigative reporter exposing its lack of nectar.

Machiavelli: And yet, look at your leaders. You have more journalists than ever, yet you still elect the best liars. Why? Because the lie feels better than the truth. You mentioned the “Justice Rage” in your article—the monkeys throwing cucumbers because they wanted grapes. That is a powerful instinct. But there is a stronger instinct: The instinct to follow the winner. If I am a monkey, and I see the Alpha Male lying to get more grapes, do I expose him? Or do I try to become his friend so I can get a grape too? Usually, the latter. The “Audit Committee” is just a weapon used by the monkeys who didn’t get any grapes.

Danny: Wow. So you see “Anti-Corruption” crusades not as moral movements, but just as power struggles?

Machiavelli: Precisely. In history, whenever a man stands up and screams “Corruption!”, he is usually just announcing that he would like to be the one holding the checkbook. It is a stratagem. He uses the “Justice Rage” of the crowd to overthrow the Alpha. But once he becomes the Alpha, he will need to distribute the meat just like the old one did. The faces change; the biology remains.

Danny: That is a bleak view, Niccolò. You’re essentially saying we can never escape this. That the “Cheating Gene” is destiny.

Machiavelli: Destiny? No. Gravity? Yes. You can build a plane to defy gravity, but you can never turn gravity off. You can build institutions to defy corruption, but you cannot turn the instinct off. The moment you turn off the engine of your “Institutions,” the plane crashes. My critique of you moderns is that you think you can reach a cruising altitude where you can turn off the engines. You think you can build a society so perfect that people stop being primates. That is dangerous. Because while you are dreaming of angels, the chimpanzees are stealing your tires.

Danny: I want to go back to the “Visceral” feeling. We talked about how corruption feels “warm” and personal. In your time, you dealt with the Medici family. They were masters of this, right? They didn’t just rule; they were godfathers.

Machiavelli: The Medici were the ultimate primate Alphas. They did not hold office initially. They simply… held the debt. They groomed everyone. If you needed a dowry for your daughter, you went to Cosimo de’ Medici. He gave you the money. He did not ask for interest. He asked for… friendship. A favor. Someday. It was beautiful. It was a web of reciprocal altruism so dense that it trapped the entire city. When they needed to crush an enemy, they didn’t need soldiers. They just called in the favors. The butcher, the baker, the judge—they all owed the Medici.

Danny: That sounds like the Mafia.

Machiavelli: The Mafia is just a crude copy of the Renaissance. But yes. It works because it relies on gratitude and fear—the two most powerful human emotions. The “Impersonal State” relies on… what? Respect for the constitution? A piece of paper? Paper burns, Danny. Gratitude lasts a lifetime. And fear lasts even longer.

Danny: You seem to admire this “Mob Boss” style of government. But didn’t it lead to constant instability? Florence was a mess. You were exiled. You were tortured. Clearly, the system wasn’t perfect.

Machiavelli: It was not perfect. The problem with the Personal State is that when the Alpha dies—or when a stronger Alpha appears—the web snaps. Chaos ensues. That is the price of biology. Nature is cyclical. Growth, decay, death. The orchid blooms, the orchid withers. The “Impersonal State” you try to build—this machine of laws—is an attempt to stop the cycle. To create something eternal. I admire the ambition. Truly. But I worry that in making the state eternal, you make it soulless. And a soulless state creates citizens who do not care if it lives or dies.

Danny: That’s a really profound point. If the system is too mechanical, we disengage. We stop voting. We stop caring. Maybe a little bit of “meat-sharing” is necessary to keep us interested in the game.

Machiavelli: A little bit of corruption is like salt. Too much, and you ruin the dish. None at all, and the dish has no flavor. You need the human touch. You need the discretion to say, “The rule says X, but because you are a good man, I will do Y.” That is mercy. Mercy is just a positive form of corruption, is it not? It is suspending the rules for a person.

Danny: I never thought of mercy as corruption, but technically… it is. It’s bypassing the standard procedure. You’re twisting my brain, Niccolò.

Machiavelli: That is my job. I am the devil’s advocate, am I not? Or just the devil, depending on who you ask.

Danny: Let’s talk about the future. If you look at our world now—algorithms, AI, digital surveillance—do you think technology will finally crush the “Cheating Gene”? Can we build an AI Prince that can’t be bribed?

Machiavelli: An AI Prince… fascinating. A ruler with no stomach for meat, no desire for mating, no cousins to employ. It would be the ultimate “Impersonal State.” It would follow the rules perfectly. And I predict you would hate it.

Danny: Why?

Machiavelli: Because you want to be able to cheat. You want to believe that you are special. That you deserve the exception. If the AI gives you a speeding ticket, you cannot cry to it. You cannot flirt with it. You cannot mention that you know the Mayor. You will feel trapped. Humans love the rules, Danny, but they love the exception even more. An unbribable ruler is a tyrant of the worst kind because he cannot be reasoned with. You will smash the machines, not because they are evil, but because they are too fair.

Danny: So, our corruption is actually a form of freedom?

Machiavelli: It is a form of agency. It is the ability to influence your fate. In a perfectly fair system, your fate is determined by the input. In a corrupt system, you can change the output if you have enough wit, enough money, or enough charm. It gives the little man hope that he can act like a big man. It gives the orchid hope it can be a bee.

Danny: You know, for a cynic, you sound strangely optimistic about our flaws.

Machiavelli: I love human beings, Danny. I just don’t trust them. There is a difference. I love them like a zoo keeper loves the lions. They are magnificent, dangerous, and predictable. If you respect their nature—if you respect that they will bite, and cheat, and steal—you can manage them. If you pretend they are tame house cats, you will get eaten.

Danny: And that brings us back to the article. “The Cheating Gene.” Your advice to our readers: Don’t fight the gene?

Machiavelli: Understand the gene. Master the gene. If you are in an office, identify the Alpha. Identify the grooming networks. Who is sharing meat with whom? Do not stand in the corner complaining that “it isn’t fair.” Join the grooming circle. Or, if you have the virtù, start your own. Be the Orchid. Be the Fox. Just don’t be the bee that gets tricked.

Danny: And if we want to be the “Anti-Corruption” guy?

Machiavelli: Then be the Lion. Roar loudly. Punish the cheaters publicly. Make an example of them. Not because it is “moral,” but because it establishes you as the new Alpha who controls the rules. Justice is just another power play, Danny. Play it well.

Danny: Niccolò Machiavelli, you are terrifying and brilliant. Thank you for making me feel incredibly insecure about my morals.

Machiavelli: Any time. Now, do you know where I can get a good espresso in this city? Or do I need to bribe someone?

Danny: I’ll buy you one.

Machiavelli: Ah, reciprocal altruism. You are learning.

Danny: There you have it, folks. The Prince himself. He argues that corruption is just the “human touch” in a cold world, and that mercy is just “positive corruption.” Is he right? Or is that just the kind of slick justification that keeps the monkeys throwing cucumbers?

0 Comments