- The Character Assassin: How the Fundamental Attribution Error Poisons Perceptions

- The Biased Detective: How Confirmation Bias Solidifies Your Opinion of Your Partner

- The Distorted Snapshot: How the Peak-End Rule Corrupts Your Shared Memories

- MagTalk Discussion

- Focus on Language

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Let’s Discuss

- Learn with AI

- Let’s Play & Learn

We like to think of love as a force of nature, an enigmatic and often irrational power that exists outside the realm of cold, hard logic. Our relationships, we believe, are built on a foundation of feeling, connection, and a unique, ineffable chemistry. We write poetry about love, not psychological treatises. We navigate our partnerships with our hearts, not with a cognitive science textbook.

And yet, for all its mystery, the day-to-day business of being in a relationship is a minefield of predictable, systematic, and often frustrating mental errors. The very same cognitive biases that skew our decisions about money and politics are running rampant in our most intimate connections. These mental shortcuts, hardwired into our brains for evolutionary efficiency, can turn minor disagreements into major blow-ups, transform quirky habits into character flaws, and warp our shared memories into something unrecognizable.

This isn’t to say that love is just a series of cognitive illusions. But understanding the psychology that underpins our interactions is like being given a secret decoder ring for our relationships. It allows us to see the hidden logic behind the seemingly illogical fights, to diagnose the source of our recurring frustrations, and to approach our partners not as adversaries in a battle of wills, but as fellow travelers equipped with the same beautifully flawed mental hardware. It’s time to pull back the curtain on the cognitive traps that shape our love lives.

The Character Assassin: How the Fundamental Attribution Error Poisons Perceptions

Picture this: Your partner says they’ll be home at 6:00 PM to help with dinner. At 6:30, they’re still not there. What’s the first thought that pops into your head? For many of us, it’s not, “I bet they got stuck in an unexpected traffic jam.” It’s, “They are so inconsiderate. They never think about me. They’re so selfish.”

This leap from a specific action (being late) to a global judgment of character (being selfish) is a classic example of the most pernicious bias in social psychology: the Fundamental Attribution Error. This is our powerful, automatic tendency to explain someone else’s behavior by attributing it to their internal disposition (their personality, character, or intentions) while underestimating the power of the situation (external factors like traffic, a demanding boss, or a sick parent).

When it comes to ourselves, however, we do the exact opposite. If we are late, it’s because the traffic was a nightmare, the boss held us late, or the world conspired against us. This is called the Actor-Observer Bias. In short: when you mess up, it’s about your character; when I mess up, it’s about my circumstances.

In a relationship, this bias is gasoline on the fire of any disagreement. It means that a simple mistake, like forgetting to take out the trash, is rarely seen as a simple mistake. It’s interpreted as a sign of disrespect, a lack of care, or laziness. We become prosecutors, building a case against our partner’s character based on isolated incidents, while acting as a lenient defense attorney for our own transgressions. Over time, this constant misattribution of motives can build a formidable wall of resentment and misunderstanding.

How to Defend Against the Fundamental Attribution Error

- Assume Good Intent (or at Least Neutral Intent): When your partner does something that upsets you, consciously force yourself to pause the character judgment. Before you default to “they’re selfish,” ask yourself: “What are three possible situational factors that could have caused this?” This practice isn’t about making excuses for them; it’s about breaking the automatic leap to a negative character attribution. It shifts you from being a prosecutor to being a detective, simply gathering information.

- Practice Situational Storytelling for Them: Actively try to tell the story from their perspective, filling it with external factors. “Okay, maybe their last meeting ran long, and their phone died, and they knew I’d be annoyed so they were stressing out in the car.” Whether this story is true or not is irrelevant. The exercise itself forces your brain to acknowledge the power of the situation and loosens the grip of the Fundamental Attribution Error.

- Communicate Your “Situation” Clearly: Since we know others are prone to judging our character, we have a responsibility to explain our circumstances when we make a mistake. Don’t just say, “Sorry I’m late.” Say, “I’m so sorry I’m late. A massive accident blocked the entire freeway, and my phone died so I couldn’t call. I know this messed up our dinner plans, and I feel terrible about it.” This provides the crucial situational context that your partner’s brain is unlikely to generate on its own.

The Biased Detective: How Confirmation Bias Solidifies Your Opinion of Your Partner

Once we have a belief, our brains work tirelessly to prove it right. This is Confirmation Bias: our tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports our preexisting beliefs. In a relationship, this bias acts like a filter, determining what we even notice about our partner.

If you’re in the blissful, early stages of a relationship—the “honeymoon phase”—you might believe your partner is the most brilliant, funny, and kind person on Earth. Confirmation bias will then cause you to see everything they do through that lens. When they tell a lame joke, you see it as “adorkable” and witty. When they are kind to a waiter, it’s proof of their profound goodness. You are gathering evidence for the “My Partner is Perfect” theory.

But this same mechanism works in reverse with devastating effect. If your relationship is strained and you’ve started to believe your partner is “lazy” or “uncaring,” Confirmation Bias will make you a world-class detective for evidence supporting that theory. You’ll notice every dish they leave in the sink and every time they forget to ask about your day. But you will be psychologically blind to the three times they did do the dishes or the moment they gave you a supportive hug. The positive data doesn’t fit the current theory (“My Partner is Lazy”), so your brain dismisses it as an exception or fails to register it at all. This creates a dangerous feedback loop: the more you believe something negative about your partner, the more evidence you will find to support it, making the belief even stronger.

How to Fight Confirmation Bias in Your Relationship

- Go on a “Positive Evidence” Hunt: If you find yourself stuck in a negative feedback loop, actively assign yourself the task of finding disconfirming evidence. For one week, your only job is to notice and write down every single thing your partner does that is thoughtful, helpful, or positive. This exercise feels artificial at first, but it forces your brain to look past its own biased filter and register the data it has been ignoring. You aren’t changing them; you’re changing what you see.

- Question Your Interpretations: When your partner does something that fits your negative theory, pause and ask, “What is another, more generous way to interpret this action?” Is leaving their socks on the floor a sign of disrespect, or is it a sign that they were exhausted after a long day and simply forgot? Forcing yourself to generate alternative interpretations breaks the automatic connection between action and negative confirmation.

- State the Positive Out Loud: When you notice something good, verbalize it. Saying, “Hey, thank you so much for making coffee this morning, I really appreciate it,” does two things. First, it reinforces the positive data in your own mind, fighting your brain’s tendency to dismiss it. Second, it provides positive reinforcement for your partner, making that positive behavior more likely to happen again. It’s a win-win that actively rewires the feedback loop.

The Distorted Snapshot: How the Peak-End Rule Corrupts Your Shared Memories

How do we remember the past? We like to think our memory works like a video camera, recording experiences accurately from start to finish. In reality, our memory is more like a biased film editor, creating a short highlight reel based on a very specific psychological quirk: the Peak-End Rule.

Pioneered by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, this rule states that our memory of an experience is not based on the average of every moment, but on an average of two specific moments: the most intense point (the “peak,” whether positive or negative) and the very end. The actual duration of the experience barely matters at all.

This has profound implications for our relationships. Think about a one-week vacation. The first five days might have been pleasantly mediocre. But on day six, you had a spectacular, peak experience—perhaps an amazing hike with a stunning view. Then, the trip ended on a high note with a lovely final dinner. The Peak-End Rule predicts that you will remember this vacation as fantastic, even though 70% of it was just okay.

Conversely, imagine a mostly wonderful vacation that ends with a horrible, stressful experience at the airport. Or a 30-minute argument where you were close to resolving things, but the last 30 seconds involved a deeply hurtful comment (a negative peak and a negative end). You will likely remember the entire vacation or the entire argument as a disaster, even if that’s a wildly inaccurate summary of the total experience. Our memories are not faithful records; they are distorted snapshots, and this distortion can color our entire perception of our shared history.

How to Manage the Peak-End Rule

- Engineer Better Endings: Since the end of an experience has such an outsized impact on its memory, make a conscious effort to finish on a high note. If you’ve had a tense but productive conversation, don’t let it just fizzle out. End it with a hug, a sincere expression of gratitude for their willingness to talk, or a small joke. This creates a positive “end” that can retroactively change the memory of the entire difficult conversation for the better. After a family outing that had some stressful moments, make sure the last thing you do is something fun and simple, like getting ice cream.

- Recognize and Label the “Peak” during a Fight: When an argument reaches a moment of extreme intensity—a negative peak—it can be helpful to call it out. Saying something like, “Okay, this has gotten way too heated. Let’s take a 10-minute break before we say something we regret,” can act as a circuit breaker. It acknowledges the peak without letting it become the defining moment of the entire interaction.

- Journal Your Experiences More Holistically: Our brains automatically create the peak-end summary. To fight this, you can create a more objective record. After a trip or a significant event, don’t just rely on your feelings. Write down what actually happened day-by-day. You might be surprised to find that a vacation you remember as “so-so” was actually filled with many small, lovely moments that your brain’s biased editor left on the cutting room floor. This practice can help build a more accurate and often more grateful narrative of your shared life.

Relationships are not about achieving a state of perfect, unbiased rationality. They are messy, emotional, and profoundly human. But by understanding these cognitive traps, we can approach our partners and ourselves with a bit more grace. We can learn to question our own stories, to challenge our immediate judgments, and to be more generous in our interpretations. We can recognize that often, the conflict isn’t between you and your partner, but between you and the ancient, glitchy, and utterly predictable wiring of the human mind.

MagTalk Discussion

Focus on Language

Vocabulary and Speaking

Alright, let’s pull some of the key language from that article and put it under the microscope. The words we choose can change the entire feel of a sentence, making it more precise, more evocative, and more powerful. Learning to use these words can do the same for your own communication. We’re going to explore ten of them, nice and conversational.

We’ll start with ineffable. In the first paragraph, we said love is built on a unique, “ineffable chemistry.” Ineffable means too great or extreme to be expressed or described in words. It’s a feeling or quality so profound you can’t quite put your finger on it. The ineffable beauty of a sunset. The ineffable sadness of a piece of music. It’s a fantastic word for those experiences that transcend language. Saying the chemistry is ineffable immediately communicates that it’s a deep, mysterious connection, not something you can list on a spreadsheet.

Next up, the word rampant. We said that cognitive biases are “rampant in our most intimate connections.” If something, usually something undesirable, is rampant, it means it is flourishing or spreading unchecked. We’ve used this one before, and it’s worth repeating because it’s so useful. You can talk about corruption being rampant in a government or speculation being rampant in a market. It paints a picture of something that is widespread and out of control, which perfectly describes how these biases operate in our relationships without us even noticing.

Let’s look at pernicious. We called the Fundamental Attribution Error the most “pernicious bias in social psychology.” We’ve also seen this one before, and its recurrence shows its versatility. Pernicious means having a harmful effect, especially in a gradual or subtle way. A pernicious lie is one that slowly poisons a relationship. A pernicious habit is one that undermines your health over time. It’s the perfect word for biases because they don’t cause a single, dramatic explosion; they cause a slow, creeping erosion of trust and understanding.

Here’s a great verb: conspired. We said that if we’re late, it’s because “the world conspired against us.” To conspire literally means to make secret plans jointly to commit an unlawful or harmful act. But we often use it more loosely and humorously to mean that events seem to have combined to cause a particular, usually negative, outcome. “The traffic, the rain, and a dead phone battery all conspired to make me miss my flight.” It’s a dramatic way of saying that multiple things went wrong at once, creating a perfect storm of situational factors.

Let’s talk about transgressions. We act as a defense attorney for our own “transgressions.” A transgression is an act that goes against a law, rule, or code of conduct; an offense. It’s a more formal and serious word than “mistake” or “error.” You can talk about moral transgressions or social transgressions. It implies the breaking of a known rule or boundary, which is often how minor mistakes feel inside the charged context of a relationship.

Now for formidable. We said that constant misattribution can build a “formidable wall of resentment.” Formidable means inspiring fear or respect through being impressively large, powerful, intense, or capable. A formidable opponent is one that is very difficult to defeat. A formidable task is one that is daunting and challenging. A formidable wall of resentment isn’t just a small barrier; it’s high, thick, and intimidatingly difficult to break down.

Let’s look at the word blissful. We talked about the “blissful honeymoon phase” of a relationship. Blissful means extremely happy; full of joy. It comes from the word bliss, which is a state of perfect happiness, often with a spiritual or heavenly connotation. A blissful silence. A state of blissful ignorance. It captures a sense of perfect, untroubled contentment, which is exactly what that early phase of a relationship feels like.

Then there’s the adjective strained. We contrasted the blissful phase with a time when a relationship is “strained.” If a relationship is strained, it is not relaxed or comfortable; it is tense and uneasy. It suggests that the connection is being pulled and put under pressure, almost to the breaking point. You can have a strained conversation or a strained silence. It perfectly describes that feeling when things are not right between two people, full of unspoken tension.

Here’s another great one: profound. We talked about the profound implications of the Peak-End Rule. Something that is profound is very great or intense, or it shows great knowledge or insight. It’s the opposite of superficial. You can have a profound effect, a profound sense of sadness, or a profound understanding of a topic. It signals depth and significance. The implications aren’t just minor; they are deep, far-reaching, and important.

Finally, let’s talk about retroactively. We said a good ending can “retroactively change the memory of an event.” Retroactively means with effect from a date in the past. Usually, you see it in a legal or financial context, like a pay raise that is applied retroactively to the beginning of the year. In our psychological context, it means something you do now can reach back in time and alter a memory or feeling from the past. It’s a powerful concept—that the present can reshape our interpretation of what has already happened.

So, we have ineffable, rampant, pernicious, conspired, transgressions, formidable, blissful, strained, profound, and retroactively. Ten words that will add a whole new layer of precision to your vocabulary.

Now for our speaking focus. Today’s skill is reframing. This is the art of changing the conceptual or emotional context of a situation to change how it is perceived. The entire article is an exercise in reframing. It reframes a partner’s lateness not as a character flaw (the initial frame), but as a potential result of situational factors (the new frame). It reframes a vacation you remembered as “bad” as a mostly good experience with a negative ending. This is one of the most powerful communication tools there is.

It’s about changing the story. When you’re in a conflict, instead of saying, “We’re fighting,” you can reframe it as, “We’re a team trying to solve a tough problem.” This simple change in language can shift the entire dynamic from adversarial to collaborative.

Here’s your challenge: The next time you face a small, frustrating situation—maybe you’re stuck in traffic, a project at work is delayed, or you have a minor disagreement with a friend—I want you to consciously practice reframing. Your task is to find at least two different ways to describe the situation. One should be the initial, negative frame (“This is a disaster, I’m going to be so late!”). The second should be a neutral or even positive reframe (“Okay, this is out of my control. This is a good opportunity to listen to that podcast I’ve been meaning to finish.”). Notice how changing the frame changes your emotional response. This isn’t about toxic positivity or ignoring problems. It’s about exercising cognitive flexibility and choosing a narrative that serves you better. This skill, more than any other, can reduce your day-to-day stress and improve your relationships.

Grammar and Writing

Welcome to the writer’s workshop, where we transform complex ideas into clear and compelling prose. Today’s challenge is about capturing the dynamic and often messy reality of a relationship, using the psychological concepts we’ve learned to add depth and insight.

The Writing Challenge:

Write a short narrative scene (around 500-750 words) that depicts a realistic conflict or misunderstanding between two people in a relationship (partners, close friends, or family members). The scene should vividly illustrate at least two of the cognitive biases discussed in the article (e.g., Fundamental Attribution Error, Confirmation Bias, Peak-End Rule).

Your narrative should:

- Establish the Context: Briefly set the scene and introduce the characters and their current emotional state.

- Show, Don’t Tell the Bias: Do not name the biases in the narrative itself. Instead, reveal them through the characters’ internal thoughts, dialogue, and actions. The reader should be able to diagnose the biases based on what you show them.

- Use Realistic Dialogue: Craft dialogue that sounds authentic to how people actually speak when they are upset or misunderstanding each other.

- Incorporate Internal Monologue: Give the reader access to the inner thoughts of at least one of the characters to clearly demonstrate their biased thinking process.

- End with a Moment of Tension or Potential Resolution: The scene doesn’t need a perfectly happy ending, but it should conclude at a pivotal moment, leaving the reader with a clear sense of the psychological dynamic at play.

This is an exercise in subtle character psychology. The goal is to create a scene that feels real and allows the reader to have that “aha!” moment of recognition.

Grammar Spotlight: Punctuation for Pacing and Emotion

In a dialogue-heavy narrative scene, your control of punctuation is your control of the rhythm and emotion. Punctuation isn’t just about rules; it’s about creating a specific effect for the reader. Let’s focus on three tools: the em dash, the ellipsis, and italics.

- The Em Dash (—): This is a versatile and dramatic mark. It can show a sudden break in thought, an interruption, or an emphatic addition. It creates a faster, more abrupt pace than a comma or parenthesis.

- For Interruption: “I just think that you never listen to—” “That’s not true! I’m listening right now!”

- For a Break in Thought: He just doesn’t get it, she thought. He thinks it’s about the dishes, but it’s about respect—or the lack of it.

- For Emphasis: “There’s only one thing I want from you right now—an apology.”

- The Ellipsis (…): An ellipsis indicates a trailing off of thought, hesitation, or an unspoken feeling hanging in the air. It slows the pace down and creates a sense of suspense or melancholy.

- For Hesitation: “I guess I just feel like… you don’t really see me anymore.”

- For Trailing Off: He looked out the window. If only she knew how tired he was…

- For Unspoken Tension: He asked, “Is everything okay?” She stared at her plate and finally said, “I’m fine…”

- Italics: Italics are primarily used for emphasis in dialogue and for showing a character’s internal thoughts.

- For Emphasis: “I told you I did call. The phone must have gone straight to voicemail.” This shows the character is stressing that specific word.

- For Internal Monologue: This is pointless, Liam thought, even as he said, “I’m trying to understand.” She’s already made up her mind about me. This creates a powerful contrast between the character’s internal reality and their external dialogue.

Writing Technique: Juxtaposing Action, Dialogue, and Thought

The most effective way to “show, not tell” a cognitive bias is to create a clear contrast between what is happening, what is being said, and what is being thought. This is where the Fundamental Attribution Error and Confirmation Bias truly come to life.

Consider this sequence to show Confirmation Bias:

- Action (Positive Data): Mark came in and put a bouquet of flowers on the table.

- Dialogue (Seemingly Neutral): “What are these for?” Sarah asked, her voice flat.

- Internal Monologue (Biased Interpretation): Flowers, she thought, a bitter taste in her mouth. He must have screwed something up at work again. He only does this when he feels guilty. Typical.

The action is positive, but the internal monologue, driven by the pre-existing theory that “Mark is thoughtless and only does nice things out of guilt,” reinterprets it as negative evidence. The flat tone of the dialogue hints at this inner state.

Consider this sequence to show the Fundamental Attribution Error:

- Action: Maya glanced at the clock. 7:45 PM. Ben was 45 minutes late. Again.

- Internal Monologue (Character Judgment): Inconsiderate. That’s the word. He is fundamentally an inconsiderate person. If he cared, he would have planned better. He just doesn’t respect my time.

- Juxtaposing Reality (The Phone Rings): Ben’s name flashes on the screen. “Maya? Oh, thank God. Listen, my car battery died in the middle of the bridge. I’ve been waiting for a tow truck for an hour and my phone was dead until a stranger let me charge it for five minutes. I am so, so sorry.”

Here, the reader is placed inside Maya’s head to witness the FAE in action. We see her leap from the action (lateness) to a sweeping character judgment. Then, the dialogue provides the contradictory situational information, creating a moment of dramatic irony and highlighting the error in her thinking.

By skillfully weaving together action, dialogue punctuated for emotion, and internal thoughts that reveal your characters’ biased processing, you can create a narrative that is not only emotionally resonant but also psychologically profound.

Multiple Choice Quiz

Let’s Discuss

These questions are designed to help you connect the dots between the psychological theories in the article and the real, lived experiences of your own relationships. Use them to start a conversation or for your own private reflection.

- The F.A.E. in Your Life: Think of a recent time a partner, friend, or family member did something that annoyed you (like being late, forgetting something, etc.). What was your immediate internal explanation for their behavior?

- Dive Deeper: Can you identify the Fundamental Attribution Error at work? Try the exercise from the article: what are three plausible situational reasons that could have caused their action? How does generating these alternative explanations change your feeling about the incident?

- Your Confirmation Bias Filter: Consider a relationship you are in (or have been in). What is one strong, recurring belief you hold or held about the other person (e.g., “they are so supportive,” “they are messy,” “they never listen”)?

- Dive Deeper: How might Confirmation Bias be affecting this belief? Can you recall specific instances where they acted contrary to this belief? Was it hard to remember them? Try the “positive evidence hunt” for a day. What do you notice that you might have filtered out before?

- The Peak-End Rule and Your Memories: Think about a memorable shared experience—a vacation, a party, or even a significant argument. What is your overall memory of that event?

- Dive Deeper: Now, try to break it down. What were the “peak” moment (most intense) and the “end” moment? How much do those two points influence your overall memory? Is it possible that your summary of the event is a distortion? How could you have engineered a better ending to improve the memory?

- Giving the Benefit of the Doubt: The article suggests “assuming good intent” as an antidote to the Fundamental attribution Error. How easy or difficult is this for you to do in the heat of the moment?

- Dive Deeper: What makes it so hard to give the benefit of the doubt to the people we are closest to? Is it because the stakes are higher? Or because we have a long history that informs our “theories” about them? What would a relationship look like where both partners made a genuine commitment to this principle?

- Becoming a Better Communicator: Knowing about these biases, what is one concrete change you can make to how you communicate in your important relationships?

- Dive Deeper: For example, you could make a rule to always explain the situation when you apologize (“I’m sorry I was grumpy, I had a terrible night’s sleep”). Or you could commit to verbalizing positive evidence (“Thank you for doing that”). Or you could practice reframing a conflict as a mutual problem to solve. What specific new habit would be most impactful for you?

Learn with AI

Disclaimer:

Because we believe in the importance of using AI and all other technological advances in our learning journey, we have decided to add a section called Learn with AI to add yet another perspective to our learning and see if we can learn a thing or two from AI. We mainly use Open AI, but sometimes we try other models as well. We asked AI to read what we said so far about this topic and tell us, as an expert, about other things or perspectives we might have missed and this is what we got in response.

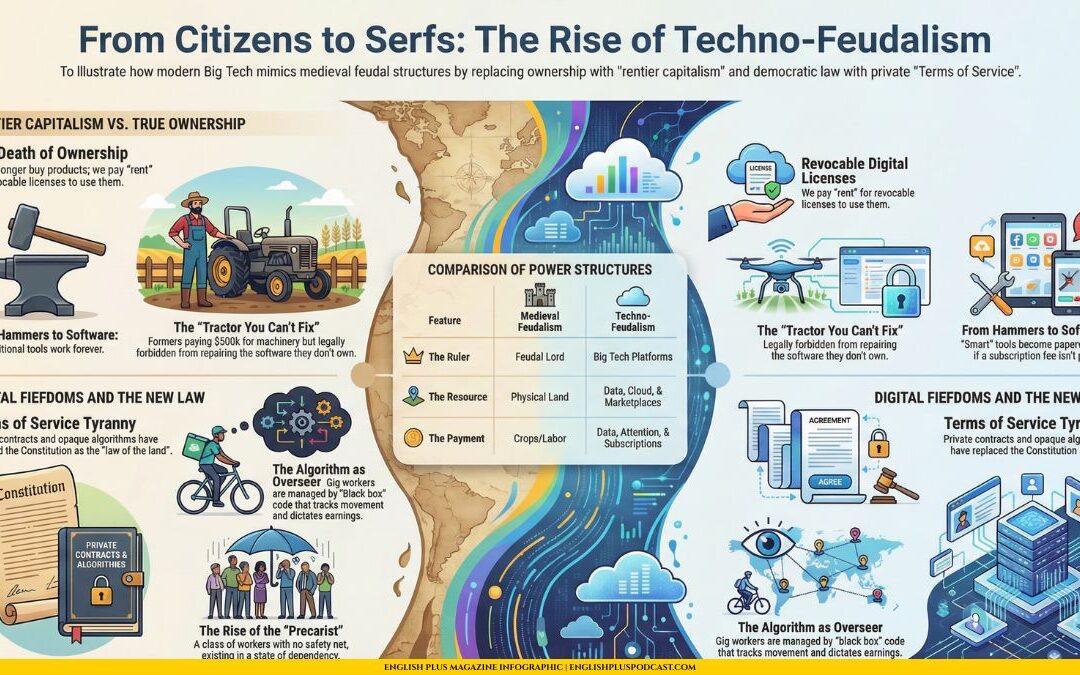

It’s been a great exploration of the “big three” biases that wreak havoc in our relationships. The Fundamental Attribution Error, Confirmation Bias, and the Peak-End Rule are truly the heavy hitters. But if we stop there, we miss a quieter, more foundational bias that sets the stage for all the others. I want to talk for a moment about Naïve Realism.

Naïve Realism is the universal and almost unshakable human belief that we see the world objectively, as it truly is. We believe our perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes are a direct, unmediated reflection of reality. And because we believe this, we naturally assume that any other rational, fair-minded person will see the world the same way we do.

This single, deeply ingrained belief is the source of so much conflict. When a partner disagrees with our political view, our opinion of a movie, or even our assessment of who should take out the trash, our brain doesn’t default to, “Oh, they have a different perspective shaped by their own unique life experiences and cognitive filters.” Our brain defaults to, “They must be biased, irrational, misinformed, or just plain difficult.”

Naïve Realism is what makes the Fundamental Attribution Error possible. The only reason we attribute our partner’s lateness to a character flaw is because we believe our perception (“being on time is a simple matter of trying hard”) is objective reality. We fail to see it as what it is: our own subjective perspective.

It’s also the fuel for Confirmation Bias. We seek evidence to support our beliefs because we are convinced our beliefs are an accurate reflection of the world. We’re not seeking to be right; we believe we are right, and we’re just gathering the facts to prove it to the other, clearly biased, person.

So, how do we combat something so fundamental? The antidote is a concept we’ve touched on before: Intellectual Humility. But in a relationship context, it’s more than just admitting you might be wrong. It’s the profound, gut-level acceptance that your experience of reality is not reality itself. It is a subjective interpretation.

The most powerful relational skill that grows from this understanding is the practice of curiosity. When your partner says something you disagree with, the Naïve Realist asks, “How can you believe something so wrong?” The intellectually humble person, who has overcome naïve realism, asks, “That’s interesting. You see it so differently from me. Can you help me understand how you see it? What am I missing?”

This shift from judgment to curiosity is, I believe, the single most transformative practice a couple can adopt. It moves the conversation away from a battle to determine whose “reality” is correct and toward a collaborative effort to understand each other’s unique, valid, and subjective worlds. Before you can debug any of the other biases, you first have to accept that your own perception is not the objective truth. It’s just your story.

0 Comments