Have you ever felt disconnected from poetry, like it’s a secret language only a few can understand? In this episode, we’re breaking down those barriers and diving into the powerful and deeply relatable poem “War Child.” Forget the jargon and philosophical nonsense – we’re exploring the raw human emotions and profound questions this poem raises about war, innocence, and our capacity for empathy.

Join us as we unpack the poem line by line, not as literary critics, but as fellow humans trying to make sense of a complex world. We’ll look at the devastating loss of innocence experienced by a child in a war-torn landscape, the soldier’s internal conflict and the weight of his choices, and the surprising moments of beauty and resilience that can emerge even in the darkest of times.

This episode isn’t about providing answers; it’s about sparking your own thoughts and reflections. We’ll pose thought-provoking questions inspired by the poem, such as: What does it truly mean to lose your innocence? How do we hold onto our humanity when faced with suffering? Where can we find hope amidst despair? And what is our responsibility towards the most vulnerable among us?

Whether you’re a lifelong poetry lover or someone who’s always felt intimidated by it, this episode will show you how poetry can be a powerful tool for understanding ourselves and the world around us. We’ll connect the themes of “War Child” to our everyday lives, exploring how the poem’s insights into dehumanization, empathy, and the search for meaning resonate with our own experiences, even far removed from the battlefield.

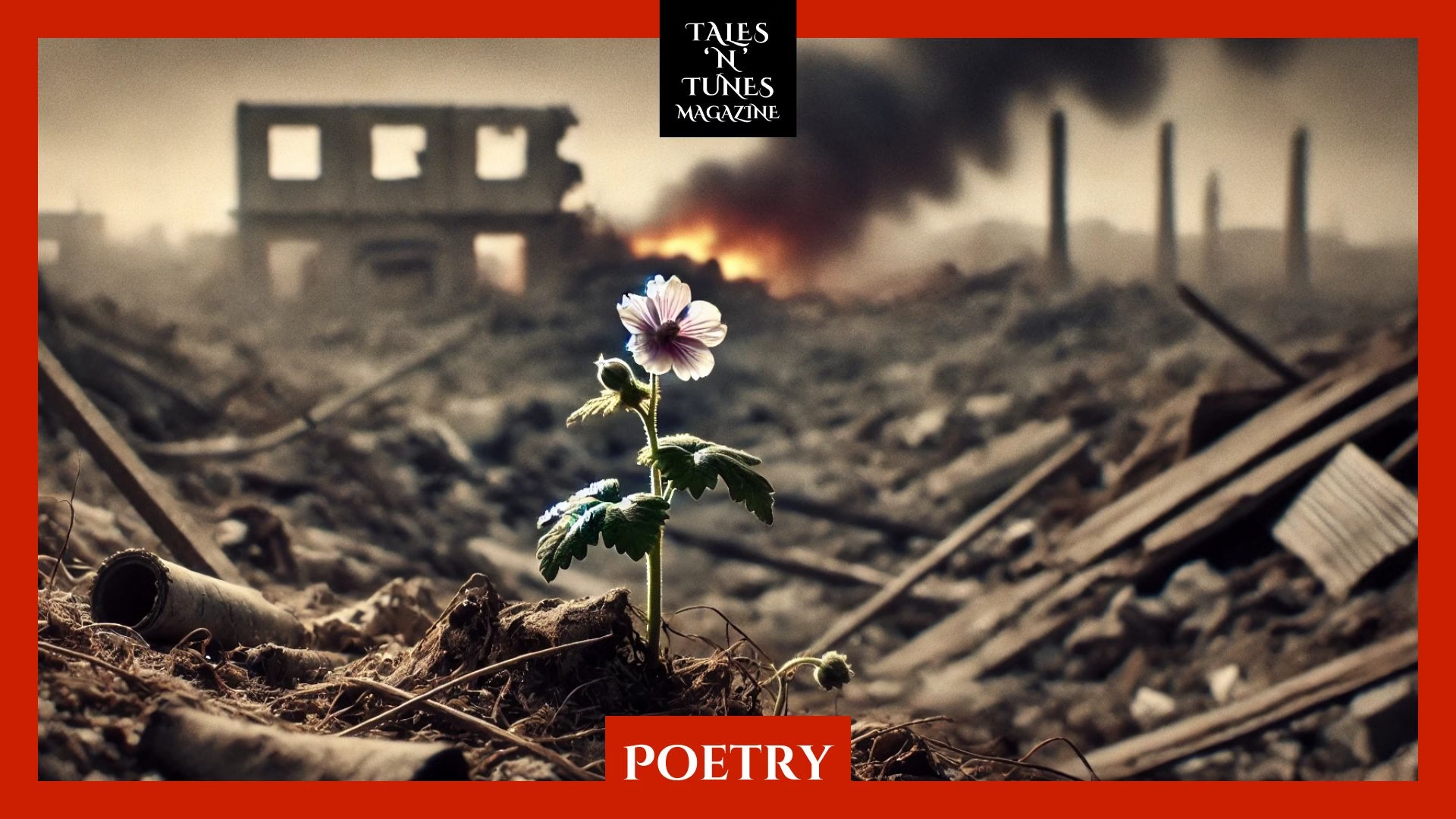

Tune in to discover the surprising power of poetry to connect us, to challenge us, and to remind us of the enduring strength of the human spirit. This episode will leave you with a new appreciation for the art of poetry and a deeper understanding of the complexities of our shared human experience. Get ready to see the unseen flowers blooming even in the most unlikely of places.

War Child

A poem by Danny Ballan

Spotted in no man’s land

searching the dead picturing a future junk yard

with him in the middle an everlasting element

something to sell and perhaps something edible

no sell-by date can frighten that old hunger

in this young skinny belly a monster terrified more

I skipped the scope and held the binoculars

I had the best view in the house

to watch him live like a saint and die like a criminal

it was a trigger away from the truth

I held my nerves and bit my orders

to see who this angel could be

so bereft of the very low measures of humanity

no formal introductions, no manly fear

no one to hold on to; all the dear have gone

so blatantly pickpocketing robbed thieves

lying too dead to be said who stole life from whom

like all gathering in a big dark room

their knives so sharpened to hit and miss

for some it may have felt like a kiss

coming from a brother

now the mixed hatred in the blood mudded the soil

what a tree in there may grow

but the boy… has gone…

replaced by men with arms

all pointing at me ready to take

I don’t blame them for I have taken many

but not this time as I say every time so confidently

I fired with all my expertise so quickly

no rock or tree was made to make men hide from me

all lay so dead, as if they were not, as if I were not

we’re already fighting in the underworld

I finally turned toward that little swindler

for a moment a dwindler I could not see

in a war too big for him to understand

nor does he the word collateral casualty

he grew smaller and smaller with time

then his eyes met mine through the scope of death

unafraid like before, he bent down to pick a flower

onto which was stuck dead a butterfly

that at that time interested him more

I froze and felt I was there on that flower

and I could not pull the trigger… I could not.

The Unseen Flowers of War: Finding Humanity in the Rubble

We often encounter poetry as something distant, locked away in dusty volumes or analyzed with a language that feels more like a secret code than a way to connect with the human heart. But what if I told you that poetry, at its core, speaks the language of our everyday lives, our unspoken fears, and our deepest longings?

Take, for instance, the poem “War Child.” On the surface, it paints a stark and brutal picture: a soldier observing a child in a war-torn landscape. But beneath the surface, it delves into questions that resonate far beyond the battlefield. It asks us about innocence lost, the dehumanizing effects of conflict, and the fragile yet persistent spark of humanity that can flicker even in the darkest of times.

Let’s walk through this poem together, not as literary critics dissecting metaphors, but as fellow humans trying to understand the complexities of our shared existence.

The poem opens with a stark image: “Spotted in no / man’s land / searching the / dead.” Immediately, we are placed in a desolate space, a place where life has been extinguished. And amidst this desolation, we find a child. This isn’t a child playing in a park or learning in a classroom. This is a child navigating a landscape of death, “picturing a future junk yard / with him in the / middle an everlasting element / something to sell / and perhaps something edible.”

Think about that for a moment. What does it say about the world this child inhabits? A world where the remnants of war are not just debris, but potential commodities, sources of survival. The innocence we associate with childhood – the carefree laughter, the boundless curiosity about toys and games – is replaced by a grim pragmatism. This child is not thinking about building sandcastles; he’s thinking about sustenance, about finding something to sell, something to eat amidst the ruins.

The poem continues, “no sell-by date / can frighten that old hunger / in this young / skinny belly a monster terrified more.” The hunger described here is not just physical; it’s a deeper hunger for survival, a primal need that overshadows the fear that should naturally accompany such a dangerous environment. This “monster” in the young belly is a powerful image, suggesting a gnawing desperation that has become a constant companion.

Then, the perspective shifts to the observer, the soldier: “I skipped the / scope and held the binoculars / I had the best / view in the house / to watch him live / like a saint and die like a criminal.” This line is incredibly potent. The soldier chooses to observe the child directly, without the detached distance of a scope meant for targeting. He sees the child not as a threat, but as someone simply trying to live. The juxtaposition of “saint” and “criminal” is jarring. What does it mean for a child in such a situation to be both? Perhaps it speaks to the moral ambiguity of war, where survival itself can be criminalized, and where even the most basic acts of resilience can seem almost miraculous, saintly.

The soldier continues, “it was a trigger / away from the truth / I held my nerves / and bit my orders / to see who this / angel could be / so bereft of the / very low measures of humanity.” The soldier is faced with a profound dilemma. He has the power to end this child’s life with a single trigger pull, yet something compels him to hold back. He wants to understand, to see the humanity in this young being who seems to exist outside the normal parameters of human experience in a peaceful world. The phrase “bereft of the very low measures of humanity” is striking. It suggests that even the most minimal expectations of human decency and care are absent in this child’s life.

“no formal / introductions, no manly fear / no one to hold on / to; all the dear have gone / so blatantly / pickpocketing robbed thieves / lying too dead to / be said who stole life from whom.” This paints a picture of utter isolation. The child has no family, no protectors, no one to offer comfort or guidance. The lines about “pickpocketing robbed thieves” highlight the chaotic and brutal nature of the conflict, where even those who steal are themselves victims of a larger theft – the theft of life itself. The question of who stole life from whom becomes a haunting reflection on the senselessness of war.

“like all / gathering in a big dark room / their knives so / sharpened to hit and miss / for some it may / have felt like a kiss / coming from a / brother.” This stanza uses the powerful metaphor of a “big dark room” to describe the indiscriminate nature of violence. In the chaos of war, the lines between friend and foe become blurred, and even acts of aggression can be perceived in distorted ways. The idea that a fatal blow might feel like a “kiss / coming from a / brother” underscores the deep psychological trauma and the breakdown of normal human relationships in such environments.

“now the mixed / hatred in the blood mudded the soil / what a tree in / there may grow / but the boy… has / gone… / replaced by men / with arms / all pointing at / me ready to take / I don’t blame / them for I have taken many / but not this time / as I say every time so confidently.” The hatred and violence have seeped into the very earth, polluting the potential for new life. The child, in his innocence and vulnerability, is lost, replaced by armed men, hardened by the same brutal realities. The soldier acknowledges his own role in the violence, the lives he has taken. Yet, in this moment, he makes a different choice.

“I fired with all / my expertise so quickly / no rock or tree / was made to make men hide from me / all lay so dead, / as if they were not, as if I were not / we’re already / fighting in the underworld.” The soldier reverts to his training, his expertise in warfare. The scene is one of swift and decisive violence, leaving no room for escape. The line “as if they were not, as if I were not” suggests a sense of detachment, a psychological coping mechanism in the face of such destruction. The idea that they are “already / fighting in the underworld” speaks to the almost surreal and otherworldly nature of war, a realm where the normal rules of life and death seem suspended.

“I finally turned / toward that little swindler / for a moment a / dwindler I could not see / in a war too big / for him to understand / nor does he the / word collateral casualty.” The soldier turns back to the child, now seeing him as a “swindler,” perhaps a term of endearment mixed with a recognition of the child’s resourcefulness in surviving. The child seems almost invisible amidst the vastness of the war, a conflict far beyond his comprehension. The phrase “collateral casualty” highlights the dehumanizing language used to describe the unintended victims of war, a concept this child is too young to grasp.

“he grew smaller / and smaller with time / then his eyes met / mine through the scope of death / unafraid like / before, he bent down to pick a flower / onto which was / stuck dead a butterfly / that at that time / interested him more.” This is the pivotal moment of the poem. The child, despite witnessing so much death and destruction, despite the soldier’s weapon being pointed directly at him, is not afraid. His attention is drawn to something beautiful and fragile – a flower with a dead butterfly on it. In this simple act, the child embodies a profound resilience, a capacity for wonder even in the face of unimaginable horror.

“I froze and felt / I was there on that flower / and I could not / pull the trigger… I could not.” The soldier experiences a moment of profound empathy, a connection with the child’s simple act of observing beauty. He sees himself in that flower, in that moment of innocent curiosity. And in that moment, the act of taking a life becomes impossible.

This poem, in its raw and unflinching depiction of war, doesn’t just show us the brutality of conflict. It also reveals the enduring power of human connection and the resilience of the human spirit, particularly in the eyes of a child.

Beyond the Battlefield: What Does This Poem Tell Us About Ourselves?

While “War Child” is set in a specific context, the themes it explores are deeply relevant to our everyday lives, even if we are fortunate enough to live in times of peace. The poem invites us to ponder some fundamental questions about humanity, innocence, and our capacity for empathy.

- What does it mean to lose innocence? We often think of childhood as a time of carefree joy and boundless possibility. But what happens when that innocence is shattered by hardship, trauma, or violence? How does it shape our understanding of the world and our place in it? Do we, in our own ways, experience moments where our innocence is tested or lost?

- How do we maintain our humanity in the face of suffering? The soldier in the poem initially observes the child with a degree of detachment, but ultimately experiences a profound moment of empathy. What are the barriers that prevent us from connecting with the suffering of others? What are the moments that break through those barriers and allow us to see the shared humanity in everyone, even those who seem very different from us?

- What is the weight of our choices? The soldier faces a life-altering decision. His training and orders might dictate one course of action, but his humanity leads him to another. In our own lives, we are constantly faced with choices, big and small. How do we weigh our options? What factors influence our decisions? And how do we live with the consequences of those choices?

- Where do we find beauty and hope in the midst of darkness? The child in the poem finds fascination in a flower and a dead butterfly amidst the devastation of war. What are the small moments of beauty and wonder that we encounter in our own lives, even during difficult times? How do these moments sustain us and offer us a glimmer of hope?

- What is our responsibility towards the vulnerable? The war child is the epitome of vulnerability. He is alone, unprotected, and facing unimaginable dangers. What is our collective responsibility towards those who are vulnerable in our own communities and around the world? How can we create a world where every child has the opportunity to grow up in safety and with dignity?

- How does language shape our perception of reality? The poem touches on the term “collateral casualty,” a phrase that can distance us from the human cost of conflict. How does the language we use to describe events and people influence our understanding and our empathy? Are there words or phrases we use that inadvertently dehumanize others or obscure the truth?

- What does it mean to truly see another person? The soldier initially sees the child as an element in a war zone. It is only when their eyes meet that he truly sees him as an individual, a fellow human being. What does it take for us to truly see the people around us, beyond our preconceived notions and biases?

These are not easy questions, and the poem doesn’t offer any simple answers. Instead, it invites us to engage in a process of reflection, to look inward and consider our own responses to these fundamental aspects of the human experience.

Poetry, at its best, doesn’t provide us with neat solutions. It offers us a lens through which to examine the complexities of life, to feel the full spectrum of human emotions, and to connect with the shared experiences that bind us together. “War Child” is a powerful reminder that even in the most extreme circumstances, the threads of humanity can still be found, woven into the fabric of our shared existence. It challenges us to look beyond the headlines and the statistics, to see the individual stories, the unseen flowers blooming in the rubble of our world, and to recognize the profound responsibility we have to one another.

By engaging with poetry in this way – not as an academic exercise, but as a way to explore our own humanity – we can break down the barriers that might make it seem distant or inaccessible. We can discover that poetry is not just for scholars or intellectuals; it is for everyone who has ever felt joy, sorrow, fear, or hope. It is a language that speaks to the core of our being, reminding us of what it means to be human in a complex and often challenging world.

0 Comments