Introduction

Have you ever had that maddening feeling… that sensation of a word perched right on the tip of your tongue, a ghost in your cognitive machine? You know the word. You know its shape, its meaning, its perfect applicability to the moment. You can almost feel its syllables, but you just… can’t… grasp it. It’s a fleeting, frustrating moment of mental misfire. We’ve all been there. We laugh it off, snap our fingers when it finally arrives two minutes too late, and move on.

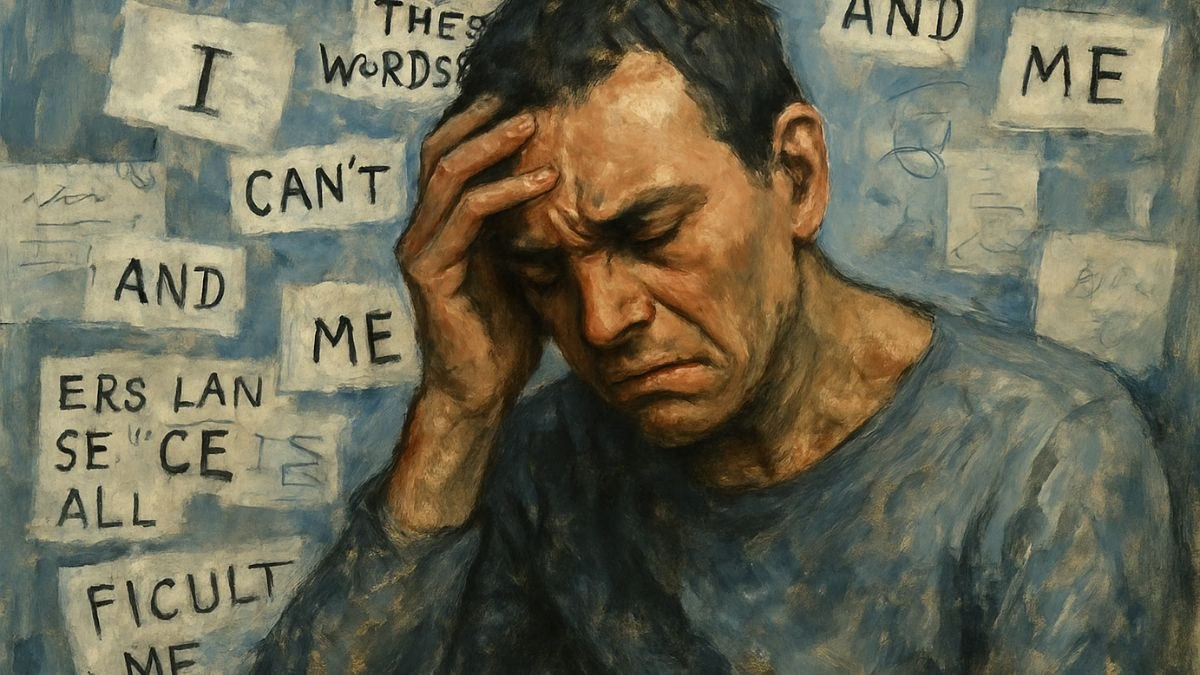

But what if that feeling wasn’t fleeting? What if it was a permanent state of being? Imagine your mind is a vast, beautiful library, filled with a lifetime of stories, ideas, jokes, and expressions of love. Now, imagine a mischievous librarian has suddenly, without warning, hidden the card catalog. The books are all still there, lining the shelves of your consciousness, but the system to find them, to retrieve them, to pull them out and share them with the world, is broken.

This isn’t a thought experiment. For millions of people, this is the daily reality of a condition called aphasia. It’s a profound disruption of one of the most fundamental human abilities: language. It’s not a loss of intelligence, not a problem with the mechanics of speech, not a sign of dementia, but a disconnect, a short-circuit in the intricate wiring of the brain that governs how we formulate, comprehend, and express ourselves through words.

Today, we’re venturing into the complex, often bewildering, and ultimately inspiring world of aphasia and language deficits. We’re going to pull back the curtain on this widely misunderstood condition. So, what are the burning questions we’re tackling in this episode?

First, what exactly is aphasia? We’ll break down the neuroscience in a way that doesn’t require a Ph.D. to understand, looking at the specific regions of the brain that act as our personal language headquarters.

Next, how does it manifest? Aphasia isn’t a monolith. We’ll explore the startlingly different ways it can present, from the halting, effortful speech of Broca’s aphasia to the fluent-yet-nonsensical torrent of words in Wernicke’s aphasia. How can one person struggle to utter a single word, while another can speak endlessly without conveying any meaning?

Then, we’ll step into the shoes of someone living with it. What is the psychological and emotional toll when the primary tool you use to connect with the world is suddenly compromised? How does it impact your identity, your relationships, your sense of self?

And finally, is there hope? We’ll look at the remarkable power of the brain to rewire itself—a concept called neuroplasticity—and the incredible resilience of the human spirit. We’ll talk about therapy, recovery, and the moving stories of those who have navigated this daunting journey.

This is a topic that touches the very core of what makes us human. It’s about more than just words; it’s about connection, identity, and the profound struggle to be understood. And a word of caution: this episode is a deep dive, but it’s by no means the final word. True knowledge, a genuine, nuanced understanding of such a complex subject, doesn’t come from a single podcast episode or a quick search online. It comes from sustained curiosity, from reading the research, from listening to the stories of those with lived experience. Consider this your gateway, your formal invitation to start that deeper journey.

So, get comfortable. Let’s explore the silent struggle, the profound resilience, and the intricate science of what happens when words fail.

Aphasia and Language Deficits

Alright, let’s start with the absolute basics. Picture your brain as the most sophisticated supercomputer ever designed. It has specialized departments for everything: vision, movement, memory, and, crucially for our discussion, language. For about 90% of right-handed people and a good chunk of left-handed folks, this language department is headquartered in the left hemisphere of the brain. It’s not just one office; it’s a whole corporate campus with different buildings responsible for different tasks.

When someone has a stroke, a traumatic brain injury, a tumor, or a neurodegenerative disease, it can be like an earthquake hitting this corporate campus. Specific buildings can get damaged, and the communication lines between them can be severed. Aphasia is the result of that damage. It’s an acquired language disorder, meaning you aren’t born with it. You had a fully functioning language system, and then something happened that disrupted it.

It’s fundamentally important to distinguish what aphasia isn’t. It is not a loss of intelligence. The person’s thoughts, ideas, and memories are often entirely intact. They are still them. The problem lies in the translation of those thoughts into language, or the translation of incoming language into thought. It’s also not a speech impediment like a stutter or a lisp, which are problems with the mechanics of producing sounds. And it’s not the cognitive decline of dementia, though they can sometimes co-occur. Aphasia is a pure, unadulterated language problem.

Now, let’s visit two of the most famous—and tragically damaged—buildings on our brain’s language campus. The first is Broca’s area, named after the 19th-century French physician Paul Broca. Think of Broca’s area as the production studio. It’s responsible for grammar, syntax, and the physical orchestration of speech. It takes your brilliant idea and figures out how to structure it into a coherent sentence, sending the right signals to your mouth and tongue.

When Broca’s area is damaged, the result is what we call Broca’s aphasia, or expressive aphasia. This is, in many ways, the most intuitively understood form. People with Broca’s aphasia know what they want to say. The idea is crystal clear in their mind. But getting it out is an immense struggle. Their speech is often described as “telegraphic”—short, choppy phrases, with grammatical function words like “is,” “the,” and “an” often omitted. For example, if they want to say, “I need to go to the store to buy some bread,” it might come out as, “Go… store… buy bread.” Each word can be a monumental effort. The frustration is palpable. Imagine knowing exactly what you want to communicate but being unable to form the sentence to do so. It’s like being a brilliant musician with a broken instrument. The music is in your soul, but you can only produce a few strained, discordant notes. What’s fascinating, though, is that their comprehension is usually quite good. They can understand what you’re saying to them, which, of course, can compound their frustration because they’re acutely aware of their own difficulties.

Now, let’s travel to another building on campus: Wernicke’s area, named after German neurologist Carl Wernicke. If Broca’s is the production studio, Wernicke’s is the comprehension and content department. It’s responsible for understanding spoken and written language and for selecting the correct words to convey meaning. It’s the brain’s internal dictionary and thesaurus.

When Wernicke’s area is damaged, we get Wernicke’s aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia. And this is where things get truly counterintuitive and, frankly, bizarre. A person with Wernicke’s aphasia can often speak fluently, with normal grammar, intonation, and rhythm. The sentences pour out. The problem? They don’t make any sense. They might use completely made-up words, or neologisms, or substitute one real word for another in a way that’s semantically nonsensical. This is sometimes called a “word salad.” They might want to tell you about their dog, but what comes out is, “The shlump is walking the frammis over there.” They are speaking, but they are not communicating.

The most heartbreaking part of Wernicke’s aphasia is that the person is often completely unaware that what they’re saying is gibberish. Because the comprehension center is damaged, they can’t process their own language to recognize its errors. They also can’t properly understand what you are saying to them. They might nod along, thinking they’re participating in a normal conversation, all while speaking a language of their own invention. Imagine living in a world where everyone, including yourself, seems to have suddenly started speaking in code. It’s a profoundly isolating and confusing experience.

These two, Broca’s and Wernicke’s, are the classic examples, but aphasia exists on a wide spectrum. There’s Anomic aphasia, where the primary difficulty is with word-finding. The grammar is fine, comprehension is fine, but the person constantly struggles to retrieve specific words, especially nouns and verbs. They might resort to talking around the word, a strategy called circumlocution. Instead of “pen,” they might say, “the thing you write with.” It’s like that tip-of-the-tongue feeling, but for countless words, all day long.

And then there’s Global aphasia, which is the most severe form. It’s the result of extensive damage to the language centers of the brain. A person with global aphasia can produce very few recognizable words and understands little to no spoken language. It is a near-total shutdown of the ability to communicate.

Living with aphasia is about so much more than the clinical definitions. It’s a psychological battle. Think about how much of our identity is tied up in our ability to communicate. We tell jokes, we share stories, we debate ideas, we comfort our loved ones, we express our needs. When that is taken away, it can lead to a profound identity crisis. People often feel trapped inside their own minds. They experience intense frustration, depression, and social isolation. Friends and family may not understand. They might mistake the difficulty in communication for a loss of intellect, speaking to the person as if they were a child, or worse, avoiding interaction altogether because it’s awkward or difficult.

The actress Emilia Clarke, from Game of Thrones, spoke powerfully about her experience with aphasia after suffering two brain aneurysms. She described the sheer panic of being on a hospital bed, unable to recall her own name, her mind a blank. She talked about feeling like her very essence, her ability to act, to communicate, was gone. Former congresswoman Gabby Giffords, after being shot in the head, had to painstakingly relearn how to speak, moving from single words to short phrases over years of intensive therapy. These public stories are so important because they shine a light on the human struggle behind the clinical term.

But here’s where the story takes a turn toward hope. The brain is not a static, hard-wired machine. It possesses a remarkable quality called neuroplasticity. This is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself, to form new neural connections and pathways. When one part of the brain is damaged, other parts can sometimes learn to take over its functions. This is the foundation of aphasia therapy.

Speech-language pathologists are the heroes of this story. They work with individuals to find new ways to communicate and to stimulate the brain’s recovery. This might involve drills and repetition, but it also involves clever strategies. Melodic Intonation Therapy, for example, uses singing to engage the right hemisphere of the brain to help produce words, essentially creating a “workaround” for the damaged left hemisphere. Constraint-Induced Language Therapy forces a person to use the verbal skills they have, rather than relying on gestures, to rebuild those pathways. Technology is also playing a huge role, with apps and devices that can help people communicate.

Recovery is often a long, arduous road. It’s rarely a complete return to baseline. But improvement is almost always possible. It requires immense patience, grueling work, and a powerful support system. But it speaks to the incredible resilience of the human brain and the indomitable nature of the human spirit. The drive to connect, to be heard, and to be understood is one of the most powerful forces within us. Aphasia may lock the words away, but it can never truly silence the person within. It’s a stark reminder that we should never take our own fluency for granted and should always listen a little more closely, a little more patiently, to those who are struggling to find their voice.

Focus on Language: Vocabulary and Speaking

Alright, that was a pretty deep dive into the world of aphasia. We threw around some complex ideas and some specific terminology. Now, I want to pivot a little. Let’s zoom in on some of the language we used. The goal here is to equip you with some powerful, versatile words and phrases that you can confidently weave into your own conversations, whether you’re discussing psychology, personal challenges, or just trying to sound a little more sophisticated in your daily chats. We’ll break down about ten of them, look at how they were used, what they really mean, and how you can make them your own.

Let’s start with a big one we used to describe the brain’s incredible ability to heal: neuroplasticity. It sounds like something straight out of a science fiction movie, but it’s a real and wonderful concept. In the script, I said, “the brain is not a static, hard-wired machine. It possesses a remarkable quality called neuroplasticity.” So, what is it? Breaking it down, ‘neuro’ refers to the nerves or the nervous system, and ‘plasticity’ refers to the quality of being easily shaped or molded. So, neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change and adapt its structure and function in response to experience or damage. Think of it like this: if a main highway in a city is blocked, neuroplasticity is the city’s ability to reroute traffic through smaller side streets, eventually strengthening those side streets until they can handle the load. In real life, you could use this when talking about learning a new skill. You might say, “Learning to play the guitar at 40 is tough, but it’s a great way to take advantage of my brain’s neuroplasticity.” It’s a fantastic word for any conversation about learning, recovery, or personal growth.

Next up is the phrase inextricably linked. I mentioned that for many, “identity is inextricably linked to our ability to communicate.” ‘Inextricably’ means in a way that is impossible to disentangle or separate. It’s a much more powerful and elegant way of saying “they’re really, really connected.” You use it when two things are so intertwined that you can’t think of one without the other. For example, you could say, “For many artists, their work is inextricably linked to their personal struggles,” or “In a global economy, the price of oil and international politics are inextricably linked.” It adds a layer of seriousness and depth to your statement.

Let’s talk about a feeling we can all relate to, but on a much grander scale in the context of aphasia: to be at a loss for words. This idiom came up when describing the feeling of being unable to speak. It’s a common, everyday phrase that perfectly captures a momentary inability to express yourself, usually due to surprise, shock, or overwhelming emotion. We used it as a relatable entry point to the much more severe experience of aphasia. You might use this all the time. “When he proposed, I was so happy I was at a loss for words,” or “After hearing the shocking news, the entire room was at a loss for words.” It’s a simple, effective idiom that everyone understands.

Now for a more specific term we touched upon: circumlocution. I described it as a strategy used in anomic aphasia, where someone might “resort to talking around the word.” That’s literally what it means. From Latin, ‘circum’ means around, and ‘locutio’ means speech. So, it’s ‘speaking around’ something. It’s using many words where fewer would do, especially in a deliberate attempt to be vague or evasive, or, in the case of aphasia, because you can’t find the specific word you need. You see politicians use circumlocution all the time when they want to avoid answering a direct question. But you could also use it in a more lighthearted way. If your friend is beating around the bush, you could tease them by saying, “Enough with the circumlocution! Just ask me if you can borrow the car.”

Here’s another great psychological term: cognitive dissonance. While I didn’t use this exact term in the main script, it perfectly describes the internal state of someone with Wernicke’s aphasia who is speaking fluently but nonsensically, yet is unaware of their errors. Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values, or when their beliefs are contradicted by their actions. For the person with Wernicke’s aphasia, the belief is “I am communicating effectively,” but the reality is that they are not. That internal conflict, even if they’re not fully conscious of it, is a form of cognitive dissonance. In everyday life, this is incredibly common. A classic example is a smoker who knows that smoking is bad for their health. The belief (“I should be healthy”) and the action (“I am smoking”) are in conflict, creating dissonance. You could say, “He’s experiencing a lot of cognitive dissonance, wanting to save the environment but also loving his gas-guzzling sports car.”

Let’s move to a more active, powerful verb: to grapple with. We didn’t use this one explicitly, but it’s the perfect verb for this topic. To grapple with something means to struggle to deal with or understand a difficult problem or subject. It implies a hands-on, intense struggle. You could say that people with aphasia must “grapple with their new reality.” It’s much more visceral than just saying they “deal with” it. You can use it for anything complex or challenging. “The committee is grappling with the budget cuts,” or “For years, she grappled with the question of her own identity.” It suggests a worthy, difficult fight.

Now, a word that is fundamental to our topic: articulate. An articulate person is someone who can express their thoughts and feelings easily and clearly. The struggle with aphasia is, at its core, a struggle to be articulate. It’s a fantastic adjective to describe a good speaker. “She gave a very articulate and persuasive presentation.” The negative form, inarticulate, is also useful. “He felt clumsy and inarticulate, unable to explain his true feelings.” Striving to be more articulate is a great goal for any language learner.

Let’s look at the word palpable. I used it to describe the frustration of someone with Broca’s aphasia, saying “The frustration is palpable.” Palpable means a feeling or atmosphere so intense that it seems almost tangible, as if you could touch it. It’s a wonderful sensory word to use for something that is technically intangible. You can’t literally touch frustration, but when it’s palpable, you can feel it in the room. You could say, “When the CEO walked in, the tension in the room was palpable,” or “There was a palpable sense of relief after the final exam.”

Next, a concept that is crucial for understanding the experience: resilience. I spoke of the “incredible resilience of the human spirit.” Resilience is the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; it’s toughness. It’s the ability to spring back into shape after being bent or compressed. It’s a cornerstone of positive psychology. We admire resilience in people who have faced adversity. You could talk about the “resilience of the city’s residents after the earthquake,” or praise a friend by saying, “Her resilience in the face of such hardship is truly inspiring.”

Finally, let’s talk about nuance. True knowledge, I said, is “a genuine, nuanced understanding of such a complex subject.” Nuance refers to a subtle difference in or shade of meaning, expression, or sound. It’s the opposite of a black-and-white, oversimplified view. Understanding nuance is key to mastering a language and understanding complex topics. When you understand the nuance of a situation, you appreciate all the small, intricate details. You could say, “To truly appreciate the film, you have to understand the cultural nuances,” or “He’s a great negotiator because he understands the nuances of human psychology.”

So there you have it: neuroplasticity, inextricably linked, to be at a loss for words, circumlocution, cognitive dissonance, to grapple with, articulate, palpable, resilience, and nuance. These are not just vocabulary words; they are tools to help you think and communicate in a more sophisticated and precise way.

Speaking: The Art of Scaffolding

Now, let’s transition into a practical speaking skill. Today, I want to talk about something I’ll call “scaffolding.” This technique is directly inspired by what we learned about circumlocution. Sometimes, a person with aphasia has to speak around a word because it’s simply inaccessible. But we can use this as a deliberate strategy to become more fluent and confident speakers.

What is scaffolding? In construction, a scaffold is a temporary structure on the outside of a building, used by workers while building, repairing, or cleaning the building. In speaking, scaffolding is building a temporary verbal structure around a word you can’t find. It’s about using the words you do have to explain the concept you’re aiming for, without pausing awkwardly or giving up. It keeps the conversation flowing and allows you to communicate your idea effectively, even if imperfectly.

Let’s say you’re trying to tell a story and you can’t remember the word “protractor”—that half-moon tool for measuring angles.

A non-scaffolded response would be: “So in geometry class, we had to use that… uh… that thing… you know… the plastic… ah, I can’t remember the word.” The conversation grinds to a halt.

A scaffolded response would be: “So in geometry class, we had to use that semi-circular tool that helps you measure angles. It’s made of clear plastic and has all the degrees marked on it.” See the difference? You successfully communicated the idea. Your listener probably knows exactly what you mean, and might even supply the word for you, “Oh, a protractor!” You’ve turned a moment of failure into a successful collaborative communication.

This skill is about fighting the panic you feel when a word escapes you. Instead of freezing, you take a deep breath and start describing. What category does it belong to? (It’s a tool, a concept, a type of food). What does it look like? (It’s circular, it’s green, it’s tiny). What does it do? (You use it for cooking, it helps you organize files).

So, here’s your challenge for this week. I want you to practice scaffolding. Find a friend or just talk to yourself. I want you to choose three complex or specific objects and describe them without using their actual names. For example, try to describe a “corkscrew,” a “USB drive,” or even an abstract concept like “déjà vu” using this scaffolding technique. The goal is not to be perfect, but to be fluid. The goal is to build those verbal bridges around the gaps, so your communication never has to stop. It’s a skill that will make you a more resilient and resourceful speaker, empowering you to grapple with any conversational challenge.

Let’s Discuss

We’ve journeyed through the clinical, the psychological, and the personal aspects of aphasia. Now, it’s time to turn the conversation over to you. Here are five questions to get you thinking and talking. Please share your thoughts in the comments section on our website; your insights enrich this community.

- Empathy and Communication: Before this episode, what were your perceptions of aphasia or other communication disorders? How has learning more about the difference between intelligence and language expression changed the way you might approach an interaction with someone who struggles to communicate?

- Ideas for discussion: Think about specific situations. How would you show patience without being patronizing? What non-verbal cues could you use to show you are engaged and understanding? Discuss the balance between helping someone find a word and giving them the space to find it themselves.

- Identity and Language: We discussed how our sense of self is often “inextricably linked” to our ability to communicate. If you suddenly lost your primary mode of expression (speaking, writing, etc.), what part of your identity do you think would be most challenged? How would you strive to express who you are?

- Ideas for discussion: Consider your profession, your hobbies, your role in your family. Are you the “funny one,” the “organizer,” the “storyteller”? How much of that relies on fluent language? Explore other forms of expression you might turn to, like art, music, or physical acts of service.

- The Role of Technology: Technology offers incredible tools for people with aphasia, from communication apps to advanced therapies. What do you see as the biggest promises and potential pitfalls of relying on technology for something as fundamentally human as communication?

- Ideas for discussion: On the plus side, discuss accessibility and the potential for a richer life. On the downside, consider the potential for over-reliance, the digital divide (not everyone has access), and whether technology can ever truly replace the nuance of human interaction.

- Resilience and Neuroplasticity in Your Life: The concepts of resilience and neuroplasticity are central to recovering from brain injury. In what areas of your own life have you witnessed or practiced these concepts? Think about learning a new skill, overcoming a personal setback, or changing a long-held habit.

- Ideas for discussion: Share a personal story. Was it learning a new language, picking up a musical instrument, or recovering from a difficult emotional period? How did you “rewire” your thinking or your habits? What did that struggle teach you about your own capacity for change?

- Educating the Community: Aphasia is a common condition, yet it remains widely misunderstood. What do you believe is the most effective way to raise public awareness and foster a more compassionate, understanding society for those with communication disorders?

- Ideas for discussion: Think beyond just “awareness campaigns.” What practical steps could be taken in schools, workplaces, or healthcare settings? How can the stories of individuals like Emilia Clarke or Gabby Giffords be used effectively to educate and inspire action?

Outro

And that brings us to the end of our deep dive into aphasia. It’s a topic that is at once clinical and deeply, profoundly human. It reminds us that language is a gift, and the drive to connect is one of the most resilient forces we possess.

Thank you so much for joining me on this journey today. If you found this exploration valuable and want to continue elevating your English while exploring fascinating topics, there are a few ways to become a deeper part of the English Plus ecosystem.

You can find transcripts for our episodes, plus a wealth of other learning resources, on our website at EnglishPlusPodcast.com.

And if you want to unlock our entire library of hundreds of podcast episodes, covering everything from history and science to literature and philosophy, you can subscribe to English Plus Premium directly on Apple Podcasts or by becoming a patron on Patreon.

For those of you who want the ultimate learning experience, I invite you to check out our All-Access subscription on Patreon. That gives you not only every podcast episode we’ve ever made, but also complete access to all of our premium audio series and our comprehensive English courses. And, on a more personal note, it’s also a way to support my own creative work, including my music and writing, for which I am incredibly grateful.

Your support allows us to keep these conversations going, to keep exploring, and to keep learning together. Until next time, take care, stay curious, and keep finding your voice.

0 Comments