The Gist

Violence as an Evolutionary Trait

One theory suggests that violence has deep evolutionary roots. Early humans lived in a world where resources were scarce and survival was uncertain. In such environments, aggression was often necessary to secure food, territory, or mates. Natural selection favored individuals who could protect their group and fend off threats. While we’ve evolved in many ways, some of these instincts remain with us, surfacing in moments of stress or fear. In this sense, violence is not just an unfortunate byproduct of humanity—it was, at one point, essential for survival.

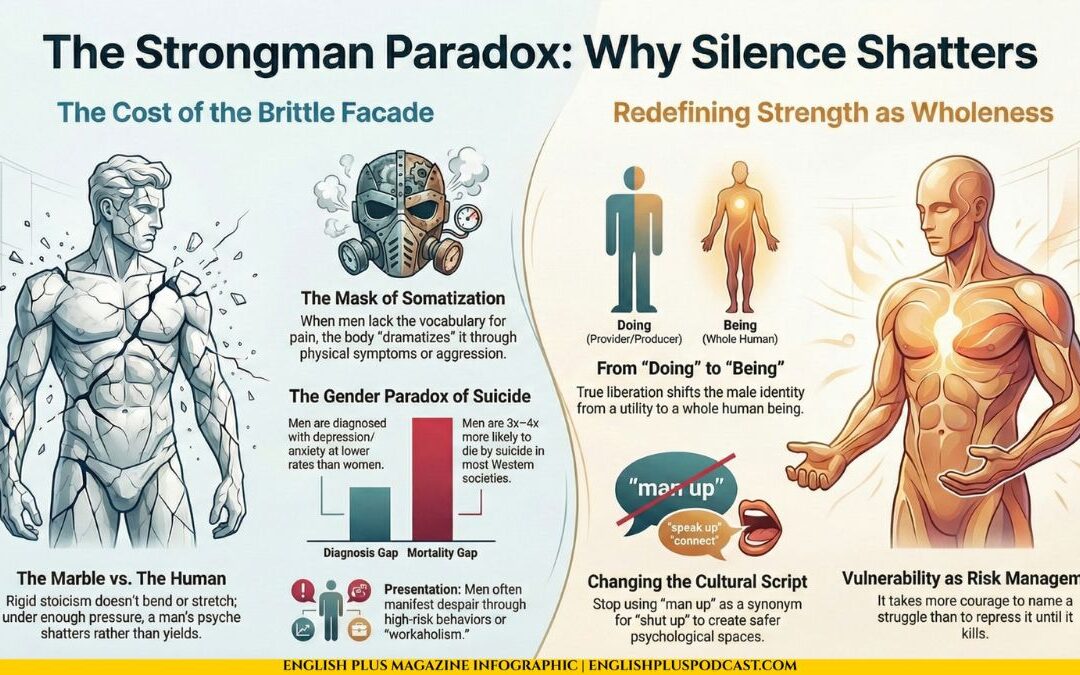

However, unlike our ancestors, modern humans have developed more sophisticated ways to resolve conflicts. Laws, moral frameworks, and societal norms act as barriers against violent behavior. Yet, the question remains: Why do we still struggle with violence if we no longer need it for survival?

The Role of Psychology and Emotion

Violence is often a response to emotions like frustration, fear, or anger. Psychologists refer to this as the frustration-aggression hypothesis—the idea that blocked goals can lead to aggression. Imagine being stuck in traffic after a long, exhausting day. That bubbling frustration can easily turn into road rage. On a larger scale, when people feel powerless or oppressed, violence can become a desperate way to regain control or express unmet needs.

Moreover, fear plays a significant role in human violence. In moments of fear, people often resort to fight-or-flight responses, with some choosing aggression to eliminate the perceived threat. This emotional response is not always rational, leading to actions that escalate conflicts rather than resolve them.

Social and Cultural Influences

Society plays a powerful role in shaping when and how people resort to violence. In some cultures, violence is normalized or even celebrated in certain contexts—think of sports or military service. Power structures also contribute to violence, with those in control sometimes using force to maintain dominance. Similarly, economic inequality, discrimination, and marginalization create environments where violence becomes a form of protest or survival.

Children who grow up in violent environments are more likely to replicate that behavior in adulthood. This phenomenon, known as the cycle of violence, shows how aggression can be passed down through generations. Breaking this cycle requires intentional efforts—through education, community support, and accessible mental health care.

Violence and Power Dynamics

Violence is often tied to power—who has it and who doesn’t. Political conflicts, civil wars, and revolutions usually stem from struggles over power and control. In these contexts, violence is a tool used to enforce authority or resist oppression. Even on a smaller scale, personal violence—such as bullying or domestic abuse—often reflects power imbalances. The one inflicting harm seeks to dominate or control the other.

However, history also shows us that power can shift. Non-violent movements, from Gandhi’s resistance in India to the civil rights movement in the U.S., have challenged the idea that violence is the only path to change. These examples remind us that power can come from unity, courage, and persistence—not just from force.

The Biology of Empathy and Cooperation

Despite the grim realities of violence, humans are also hardwired for empathy and cooperation. Our ability to connect with others emotionally is part of what makes us human. Acts of kindness, charity, and solidarity show that we are just as capable of building bridges as we are of tearing them down. The same brain that drives aggression can also drive compassion.

Social bonding plays a critical role in reducing violence. When people feel connected to their community, they are less likely to engage in destructive behavior. This is why fostering empathy—through education, storytelling, and meaningful conversations—can help create peaceful societies.

Breaking the Cycle of Violence

Understanding why humans engage in violence is the first step toward reducing it. It’s not enough to suppress violent behavior; we need to address its root causes. Providing mental health support, addressing inequality, and teaching conflict resolution skills are essential for creating lasting peace. Small actions—like listening without judgment, choosing dialogue over confrontation, and standing up against injustice—can have ripple effects in our communities.

At the end of the day, violence is not inevitable. Just as we have evolved beyond many of our primal instincts, we can evolve toward a more peaceful way of living. The choice lies with us—both as individuals and as a society.

Final Thoughts

Violence may be part of our history, but it doesn’t have to define our future. By understanding the emotional, social, and cultural roots of aggression, we can work toward a world where violence is no longer the default response to conflict. It starts with small shifts—recognizing when frustration turns to anger, choosing kindness over dominance, and promoting empathy in our daily lives. The path to peace isn’t easy, but it’s worth pursuing. After all, if humans have the capacity for violence, we also have the capacity to create a better, kinder world.

Let’s Talk

So, why do humans engage in violence? It’s such a complicated question, isn’t it? And the more you think about it, the more layers you uncover. Sure, evolution explains a lot—our ancestors had to fight to survive, whether for food, territory, or safety. But here’s the thing: we’ve come a long way since the days of hunting with spears. So why does violence still show up in our world, in everything from road rage to global conflicts?

Let’s talk about frustration for a second. Ever been in one of those moments where everything just seems to go wrong? Maybe your Wi-Fi’s down, your coffee spills, and then—bam!—someone cuts you off in traffic, and suddenly, you feel this surge of anger you can’t explain. That’s frustration boiling over, and it’s something we all deal with. But the key difference is what we do with it. Some people lash out, while others take a deep breath and move on. Why do you think that is? What makes one person explode and another just shrug it off?

Fear plays a huge role too. Think about it—how often do people resort to aggression because they’re scared? It’s not always the obvious kind of fear, like fear for safety. Sometimes it’s fear of losing control, fear of being judged, or fear of change. Ever notice how people can get really defensive when they feel out of their depth? It’s almost like they think being aggressive will protect them from whatever they’re afraid of. But does it really? Or does it just make things worse?

Then there’s the whole issue of learned behavior. If someone grows up in an environment where violence is the norm, it becomes part of how they respond to challenges. That’s what’s so tricky about the cycle of violence—it’s hard to break when it’s all you’ve known. But here’s the good news: just like violence can be learned, peace can be learned too. What if, instead of reacting to frustration or fear with anger, we taught ourselves—and others—to pause, reflect, and choose empathy instead?

Power dynamics are another big part of the picture. Think about personal relationships, workplaces, even politics—violence often shows up when people feel powerless or when those with power feel threatened. It makes you wonder: How much of the violence we see is rooted in people trying to assert control over something—or someone—they fear losing? And what if we could flip that narrative? What if power didn’t have to mean control over others, but instead, control over ourselves?

And let’s not forget about empathy. The same brain that fuels aggression is also wired for compassion. It’s almost like we’re standing on a seesaw between these two forces—some days tipping toward anger, other days toward kindness. What if we could tilt the balance more consistently toward empathy? Imagine a world where people paused to think about how their actions would affect others before they acted. Sounds simple, but it’s not, right? It takes practice, especially when frustration or fear kicks in.

Here’s a question to consider: When was the last time you stopped yourself from saying or doing something hurtful, even though you were really tempted? How did that feel afterward? And what if more of us did that—if we chose not to escalate conflict, even when it would’ve been the easy thing to do?

It all starts with small choices—recognizing that frustration is temporary, that fear can be managed, and that violence isn’t inevitable. We may not be able to solve the world’s problems overnight, but every time we choose kindness over anger, or empathy over judgment, we move the needle a little closer toward peace. Maybe it’s not about eliminating violence entirely—it’s about learning how to handle the forces that drive it and recognizing that the real power lies in choosing how we respond.

Let’s Learn Vocabulary in Context

Let’s explore some of the key words and phrases from our discussion about why humans engage in violence and how they can also choose empathy. These words aren’t just for deep conversations—they pop up in everyday life and can help us better express ourselves when we’re dealing with emotions, conflict, or personal challenges.

First, let’s start with frustration. This word describes that feeling you get when something is blocking your goals, like being stuck in traffic when you’re already late. We saw how frustration can lead to aggression, but it’s important to remember that frustration isn’t always bad—it’s how we respond to it that matters. “I felt so much frustration when my computer crashed, but instead of yelling, I took a walk to clear my head.”

Aggression is another important word. It refers to hostile or violent behavior, whether it’s physical or verbal. We might say, “The coach told his team to play aggressively, but not unfairly.” Aggression isn’t always about violence—it can also show up in subtle ways, like interrupting someone during a conversation.

Now, let’s talk about fear. It’s one of the oldest emotions we have, and it often drives us to act in ways we normally wouldn’t. Fear isn’t always obvious, though—it can hide behind anger or defensiveness. “Her fear of failure made her avoid trying new things, even though she wanted to.”

Empathy is the ability to understand and share someone else’s feelings, even when we haven’t experienced the same thing. Empathy helps us connect with others on a deeper level. “When his friend lost a job, he showed empathy by listening instead of offering quick advice.”

Cycle of violence refers to the idea that violent behavior is often passed down through generations. If someone grows up in a violent household, they may be more likely to repeat that behavior. But cycles can be broken. “She worked hard to break the cycle of violence by seeking therapy and building healthier relationships.”

Power dynamics come into play in many situations, from personal relationships to workplaces and politics. They describe the way power is distributed between people, which can sometimes lead to conflict. “The conversation became tense because the power dynamics between the manager and employee were out of balance.”

Conflict resolution is the process of finding a peaceful solution to a disagreement. It’s a skill that’s useful not just in work settings but also in personal relationships. “They used conflict resolution techniques to settle the argument without anyone feeling hurt.”

Let’s move to compassion—a word closely related to empathy, but with an active twist. Compassion is empathy in action. It’s not just understanding someone’s pain; it’s also wanting to help. “She showed compassion by volunteering at the shelter every weekend.”

Non-violent movements refer to efforts to bring about change without the use of force. They rely on peaceful methods like protests, strikes, or civil disobedience. “The civil rights movement used non-violent strategies to push for equality.”

Finally, let’s look at response versus reaction. A response is a thought-out action, while a reaction is often impulsive. Learning to respond instead of react is a powerful tool for managing emotions. “When the comment upset him, he paused and responded calmly instead of reacting with anger.”

Here are a couple of questions to reflect on: What’s one situation where you found it hard to manage frustration, and how did you handle it? And when was the last time you chose to respond thoughtfully rather than react emotionally?

0 Comments