A Picture of Ignorance

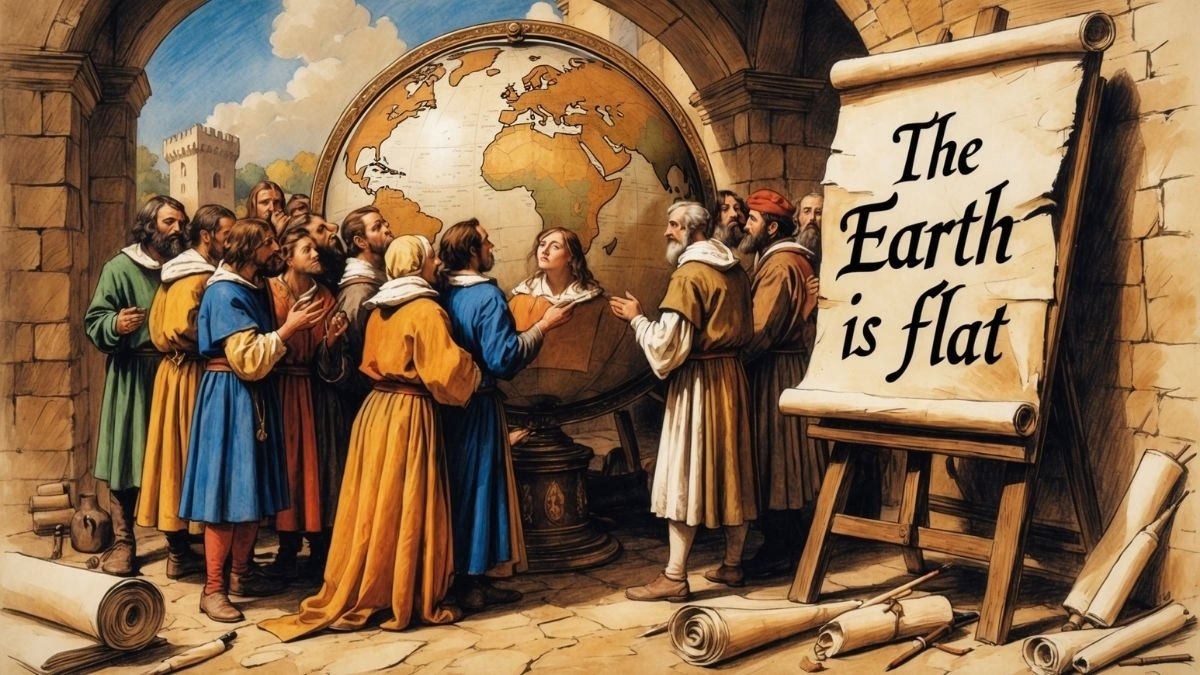

Picture a scene from a history book or a cartoon. It’s 1492. Christopher Columbus stands proudly on the deck of the Santa Maria, sailing west. Back on the docks, a crowd of people wring their hands, terrified. They stare at the horizon, convinced that any minute now, Columbus and his crew will sail right off the edge of the world into a sea full of monsters. This image is powerful. It paints a picture of a brave, forward-thinking explorer defying the ignorance of a superstitious and backward medieval world. It’s a fantastic story of progress against dogma. The only problem? It’s almost entirely false. It’s time to bust one of the most enduring and widespread historical fallacies: the flat earth myth.

Ancient Knowledge: The World is a Sphere

Let’s get one thing straight right away: the idea that the Earth is a sphere is not a modern discovery. It’s not even a Renaissance discovery. It’s ancient. As far back as the 6th century BC, the Greek philosopher Pythagoras (yes, the triangle guy) proposed a spherical Earth, likely based on aesthetic and philosophical grounds. A century later, Aristotle provided solid, observable evidence. He pointed out that travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon. He noted that the Earth’s shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse is always round. And he observed that as ships sail away, their hulls disappear from view before their masts do—a clear indication of a curved surface. This wasn’t some obscure theory; this was mainstream Greek science.

Measuring the Globe (Before It Was Cool)

The ancient Greeks didn’t just know the Earth was round; they measured it. In the 3rd century BC, the brilliant librarian of Alexandria, Eratosthenes, pulled off one of the most incredible calculations in history. He heard that in a city to the south, Syene, on the summer solstice, the sun was directly overhead and cast no shadows at noon. He knew that in his own city, Alexandria, on the same day, the sun did cast a shadow. By measuring that shadow’s angle and knowing the distance between the two cities, he used simple geometry to calculate the circumference of the entire planet. And his calculation was astonishingly accurate, off by only a small percentage. This knowledge wasn’t lost; it was preserved and passed down through Roman and into medieval scholarship.

The Medieval Scholar’s Worldview

So what did the educated person in the Middle Ages believe? They believed the Earth was a sphere. The leading and most influential scholars of the era, like the Venerable Bede in the 8th century and Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, explicitly wrote about the Earth’s sphericity as a known fact. It was taught in the early medieval universities. The Globus Cruciger, a golden orb topped with a cross, was a common symbol of royal power throughout Christendom, representing the Earth (the globus) under the dominion of Christ. You can’t have a globus if you think the world is a flat disc. The average, uneducated peasant plowing a field probably didn’t think about the shape of the Earth at all—it was irrelevant to their daily life—but they certainly weren’t being taught it was flat by the church or any other authority.

The Columbus Controversy: It Was About Size, Not Shape

If everyone knew the world was round, what was the big deal with Columbus’s voyage? The debate wasn’t about the shape of the Earth; it was about its size. Columbus was a passionate but deeply flawed navigator who believed the Earth was much, much smaller than it actually is. He had cherry-picked calculations and wildly underestimated the circumference. The scholarly experts at the Spanish court who advised Queen Isabella didn’t tell him he’d fall off the edge. They told him his math was wrong. They correctly argued that the ocean between Europe and Asia was far too vast to cross and that he and his crew would run out of supplies and starve long before they reached the Indies. And you know what? They were 100% right. Columbus didn’t prove the world was round. He got lucky that there happened to be an entire continent, a “New World,” sitting right where he thought Asia should be.

So Who Started the Myth?

The flat earth myth is a relatively modern invention. It was popularized in the 19th century, particularly by two American writers: Washington Irving, in his romanticized and largely fictional 1828 biography of Columbus, and later by John W. Draper, a scientist who wanted to create a narrative of an eternal conflict between science and religion. They promoted the idea of a “dark age” of religious dogma where the church suppressed knowledge and enforced a flat-earth view, with brave scientists like Columbus as the heroes of reason. It was a compelling story, but it was bad history. It was propaganda designed to make the post-Enlightenment era feel superior to the past.

Why It Matters

Busting this myth isn’t just about being a historical stickler. It matters because the flat earth myth distorts our view of the past, creating a caricature of an entire millennium of human history. It feeds into a lazy narrative of “progress” that ignores the real intellectual achievements of the Middle Ages. It teaches us to be critical thinkers, to question the stories we’re told, even the ones that seem like common knowledge. The truth is often more complex, more nuanced, and far more interesting than the myth.

So, what other “facts” that you take for granted might be worth a second look?

Dive into the comments and share a “common knowledge” myth you’ve discovered to be false!

0 Comments