Addiction is a deeply misunderstood topic, often clouded by stigma and misinformation. For a long time, addiction was seen as a moral failing or a sign of weak character. However, advancements in neuroscience have provided new insights into addiction, suggesting it behaves like a disease—one that changes the brain and affects behavior. This understanding has transformed the way healthcare professionals approach treatment, but it’s also sparked debate. In this article, we’ll explore both sides of the argument: Can addiction really be considered a disease? And if so, what does that mean for individuals, families, and society at large?

What Defines a Disease?

Before diving into addiction, it’s important to understand what qualifies something as a disease. A disease is generally defined as a condition that impairs normal functioning, involves identifiable signs and symptoms, and has specific biological or environmental causes. Diseases are not always curable, but they can often be managed with appropriate treatment and lifestyle changes.

Addiction fits this framework in many ways. It involves changes to the brain’s reward system, impairing an individual’s ability to make healthy choices and control impulses. Like other chronic diseases such as diabetes or heart disease, addiction can require long-term treatment and management to achieve recovery.

The Brain and Addiction: How It Works

Addiction alters the way the brain processes pleasure, motivation, and control. Substances like alcohol, drugs, and even behaviors such as gambling flood the brain with dopamine, a neurotransmitter that creates a feeling of euphoria. Over time, the brain adapts to these surges by reducing its natural dopamine production, making it harder for individuals to feel pleasure without the addictive substance or behavior.

These changes impact the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for decision-making and impulse control. As a result, individuals struggling with addiction find it increasingly difficult to resist cravings, even when they are aware of the harmful consequences. This neurological shift supports the idea that addiction is not simply about choice but involves real, measurable changes in brain function.

The Disease Model of Addiction

The disease model of addiction frames addiction as a chronic, relapsing condition that can be managed but not always cured. This model emphasizes that addiction is not a failure of willpower but a complex interaction of genetic, psychological, and environmental factors. For example, some people may have a genetic predisposition to addiction, while others may develop it as a coping mechanism for trauma or stress.

The disease model encourages a compassionate approach to treatment, focusing on medical interventions like therapy, medication, and support groups. Just as we wouldn’t shame someone for needing insulin to manage diabetes, the disease model promotes understanding that individuals with addiction need appropriate care and support.

The Debate: Is Addiction Really a Disease?

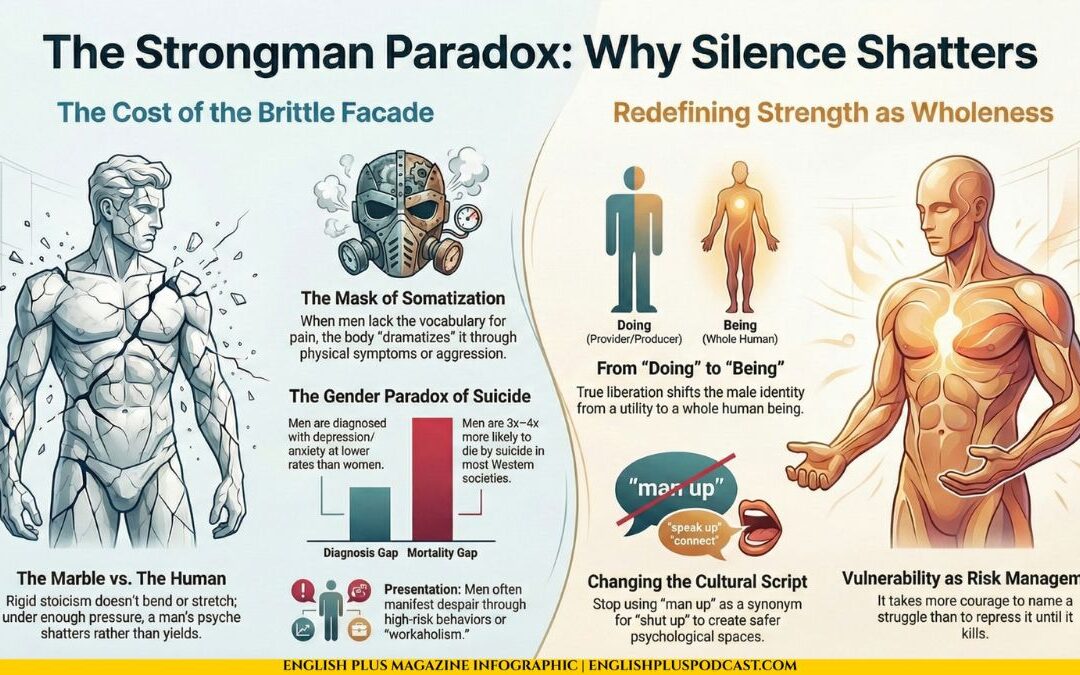

Despite the scientific evidence, not everyone agrees that addiction should be classified as a disease. Some argue that labeling addiction as a disease removes personal responsibility, making it harder for individuals to recognize their role in recovery. Others worry that the disease label could foster a sense of hopelessness, discouraging people from seeking help.

Critics also point out that addiction involves an element of choice—after all, the initial decision to use a substance or engage in a behavior is voluntary. They argue that framing addiction solely as a disease overlooks the importance of personal accountability in overcoming it.

However, proponents of the disease model counter that acknowledging addiction as a disease does not eliminate responsibility—it simply shifts the focus toward effective treatment. They argue that recognizing addiction as a disease helps reduce stigma, encouraging more people to seek help without fear of judgment.

What This Means for Treatment

Whether or not you view addiction as a disease, the reality is that treating it requires more than just willpower. Effective recovery often involves a combination of medical treatment, therapy, and community support. Medications like methadone and naltrexone can help manage cravings, while behavioral therapies address the emotional and psychological aspects of addiction.

Support systems such as 12-step programs or peer recovery groups provide individuals with the connection and accountability they need to stay on track. Just like managing other chronic conditions, recovery from addiction involves setbacks and progress, making long-term support essential.

Why This Conversation Matters

The way we understand addiction shapes the way we respond to it—as individuals, as families, and as a society. If we continue to view addiction as a moral failure, we risk isolating those who need help the most. But if we embrace the disease model, we open the door to more compassionate, effective approaches to treatment and recovery.

The debate over whether addiction is a disease is more than just an academic argument—it influences policies, healthcare practices, and the way we support loved ones struggling with addiction. Recognizing addiction as a disease can help reduce shame and create more space for healing, both for those directly affected and for the people who care about them.

So, can addiction be considered a disease? The science says yes, but the conversation is far from over. Addiction involves both personal choice and biological factors, and recovery requires both responsibility and support. Whether you lean toward the disease model or not, one thing is clear: addressing addiction with empathy and understanding is the key to making a difference.

Let’s Talk

So, let’s dive a bit deeper into this idea—can addiction really be considered a disease? It’s not exactly a straightforward question, is it? I mean, on one hand, there’s the science telling us that addiction rewires the brain, messes with dopamine levels, and changes the way people make decisions. On the other hand, there’s that tricky little thing called choice. After all, no one forces that first drink or puff on someone, right? Or is that too simple a way to look at it?

The thing is, once addiction takes hold, choice becomes a whole different ballgame. Imagine this: you’re driving a car, totally in control, but then the steering wheel locks and the brakes stop working. That’s kind of what happens with addiction. At first, it feels like you’re driving just fine, but suddenly, the controls don’t respond the way they used to. That’s the effect of those brain changes—decisions that seem easy for others become incredibly hard for someone struggling with addiction.

It’s easy to wonder, though—if addiction is a disease, why does it carry so much stigma? Think about it. If someone has heart disease or diabetes, people rush to offer support and understanding. But when it’s addiction? The response is often judgment, like, “Why can’t they just stop?” It’s almost as if people think addiction is a moral failure instead of a medical issue. And that stigma makes it even harder for people to reach out for help. Have you ever caught yourself feeling judgmental about someone’s struggle with addiction and then stopped to wonder, “What if it isn’t that simple?”

I think one of the biggest challenges is that addiction exists in this gray area—it’s a disease, yes, but it also involves personal responsibility. Recovery isn’t passive; it takes work, often a lot of it. But then again, so does managing any chronic condition. A person with diabetes still has to watch their diet and take their medication regularly. Addiction is no different in that sense—it requires ongoing effort and support to stay on track.

What’s really fascinating—and kind of hopeful—is how many different ways there are to recover. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. For some people, medication helps reduce cravings, while others find strength in therapy or support groups. And then there’s the importance of community. It’s wild how powerful connection can be in recovery. Whether it’s AA, peer support groups, or just having family and friends who get it, recovery thrives on connection. Have you ever noticed how much easier things are when you’ve got someone rooting for you, even if it’s just a workout buddy or a friend who checks in?

Another interesting point is how addiction challenges our idea of self-control. It makes you wonder—how much of what we think of as “free will” is shaped by our biology? If brain chemistry can hijack decision-making, does that change how we think about willpower? And if we accept addiction as a disease, does that mean we need to rethink how we view accountability, not just for addiction, but for other behaviors too?

Ultimately, whether or not you fully embrace the disease model, what really matters is the approach. Compassion, understanding, and effective treatment are key. Punishment and shame don’t help—they just push people further into isolation. And isn’t that the opposite of what we want? Recovery isn’t about perfection; it’s about progress. It’s about finding ways to heal, even when the road is messy and full of detours.

What do you think? Do you believe addiction should be treated like a disease, or do you feel like personal responsibility plays a bigger role? And here’s a deeper question—if we start seeing addiction as a disease, how do we reshape the way society supports people in recovery? Because let’s face it: we all know someone, directly or indirectly, who has faced addiction. And how we respond could make all the difference.

Let’s Learn Vocabulary in Context

Let’s explore some of the key vocabulary from our conversation about addiction and how these words apply to real life. First up is “stigma.” Stigma refers to the negative attitudes or shame associated with something, like how people with addiction often feel judged. You’ve probably felt stigma before, even in smaller ways—like when someone looks down on you for making a lifestyle choice they don’t agree with. It’s that invisible label that can make asking for help feel impossible.

Next is “willpower.” Willpower is the inner strength we rely on to make tough decisions, like saying no to dessert or getting out of bed early. In the context of addiction, willpower alone often isn’t enough, which can feel confusing. It makes us realize that some challenges, like addiction, require more than just personal determination.

“Relapse” is another important term. It means slipping back into old habits after a period of recovery. In addiction, relapse is common, but it doesn’t mean failure—it’s just part of the process. We use the word in other areas too: “I tried to quit caffeine, but I relapsed after a week.” It’s a reminder that progress isn’t always linear.

Then we have “recovery.” Recovery is about regaining health and well-being after a setback. It’s not just about addiction—recovery can apply to anything, from recovering from an illness to bouncing back from burnout. It’s a word that reminds us healing takes time.

“Craving” is something we’ve all experienced, whether it’s for chocolate, coffee, or a social media fix. Cravings are intense desires that can be hard to ignore. In addiction, cravings are often overwhelming, driven by changes in brain chemistry, which explains why quitting isn’t just about willpower.

“Accountability” refers to taking responsibility for your actions. It plays a big role in recovery, where individuals often rely on support systems to stay accountable. But accountability shows up in everyday life too: “I told my friend I’d meet them at the gym, so now I have to go.”

Let’s talk about “isolation.” Isolation means being disconnected from others, either physically or emotionally. Addiction often leads to isolation, making recovery even harder. In real life, isolation isn’t always obvious—it can be the feeling of being alone in a crowded room or scrolling through social media and realizing you don’t really feel connected.

“Intervention” is another key term. An intervention is when someone steps in to help before things get worse. In addiction, it’s often a meeting where loved ones offer support and encourage treatment. But interventions happen in other ways too: “My boss had to intervene before the project fell apart.” It’s about stepping in at the right moment.

“Compassion” is essential in understanding addiction. Compassion means recognizing someone’s pain and responding with kindness, not judgment. In everyday life, compassion can be as simple as saying, “I understand you’re having a tough day—let me know if I can help.”

Lastly, let’s talk about “support.” Support means offering help or encouragement when someone needs it. Recovery from addiction is nearly impossible without support—whether it’s from family, friends, or community groups. And we all need support from time to time, whether it’s with a big challenge or a small struggle.

Here are a couple of questions to think about: Have you ever faced a craving or a setback and needed support to get through it? And how do you show accountability in your own life, especially when things get tough?

0 Comments