- Introduction

- Oppenheimer: A Genius Born

- Quantum Leap: Oppenheimer’s Theoretical Explorations

- From Academia to Manhattan: The Shift in Focus

- The Manhattan Project: The Making of The Atomic Bomb

- Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Age Begins

- Oppenheimer: The Remorseful Architect

- Red Scare: The Trial of J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Legacy of Oppenheimer: The Father of The Atomic Age

- Keywords

- Key Takeaways

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Why did Oppenheimer choose to study theoretical physics, specifically?

- What was Oppenheimer’s relationship with other leading scientists of his time?

- How did Oppenheimer’s work influence the field of theoretical physics beyond the atomic bomb?

- How did the public perceive Oppenheimer during his lifetime, especially during and after the Manhattan Project?

- How did Oppenheimer’s work impact the development of nuclear energy for peaceful uses?

- What were some of the main criticisms of Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project?

- How did Oppenheimer’s personal life influence his professional career?

- Did Oppenheimer ever express regret over his involvement in the development of the atomic bomb?

- How did the scientific community react to Oppenheimer’s security hearing and the subsequent revocation of his security clearance?

- What is Oppenheimer’s most lasting contribution to science and society?

- Myth Buster

- Myth: Oppenheimer single-handedly built the atomic bomb

- Myth: Oppenheimer was a Communist

- Myth: Oppenheimer was a traitor

- Myth: Oppenheimer regretted his work on the atomic bomb

- Myth: Oppenheimer was a pacifist

- Myth: Oppenheimer’s work was solely focused on nuclear physics

- Myth: Oppenheimer was always against the development of the hydrogen bomb

- Myth: Oppenheimer was a loner and an outcast among scientists

- Myth: Oppenheimer’s scientific career ended after his security clearance was revoked

- Myth: Oppenheimer was solely a physicist

- Test Your Knowledge

Introduction

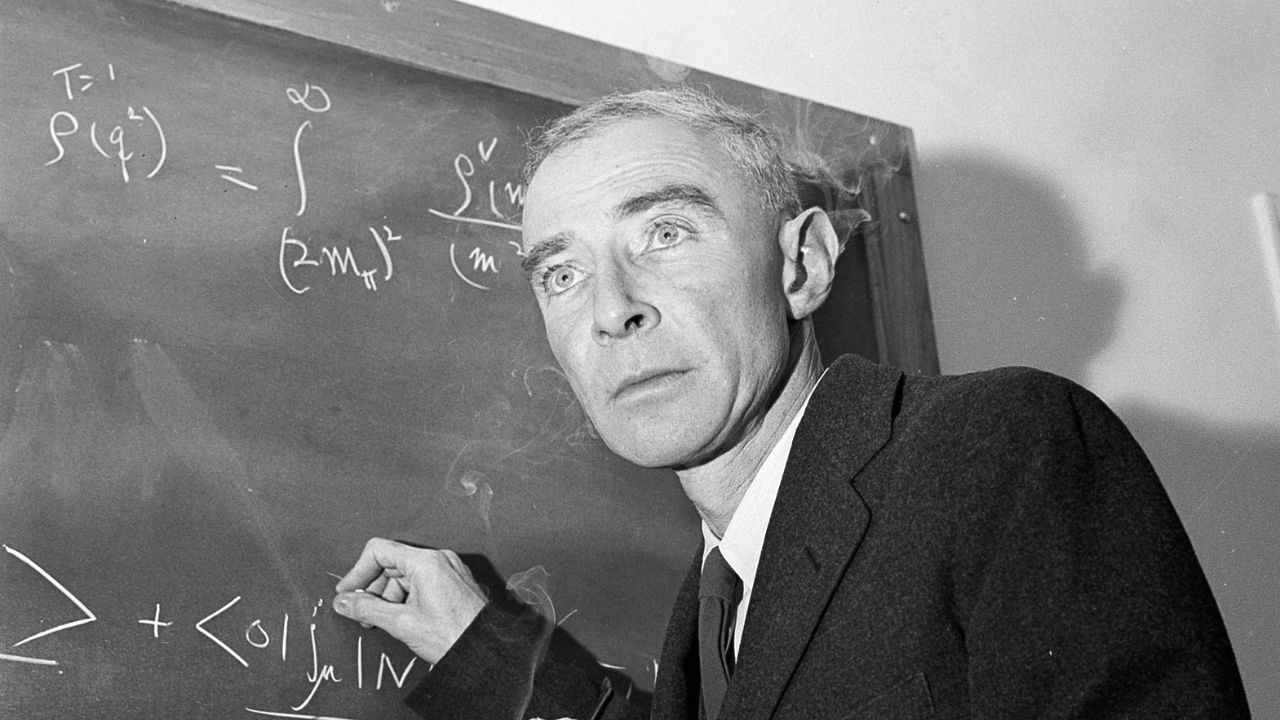

In a world that was precariously balanced on the brink of devastation, one man stood at the precipice, grappling with the power to annihilate or the power to progress. This man was J. Robert Oppenheimer – the ‘father of the atomic bomb’. His life and works continue to elicit profound reflections on the complex relationship between science, ethics, and society. In this introductory article to our series “Unraveling The Atomic Age: The Life and Legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, we will begin to explore this enigmatic figure’s journey, and how it forever altered the course of human history.

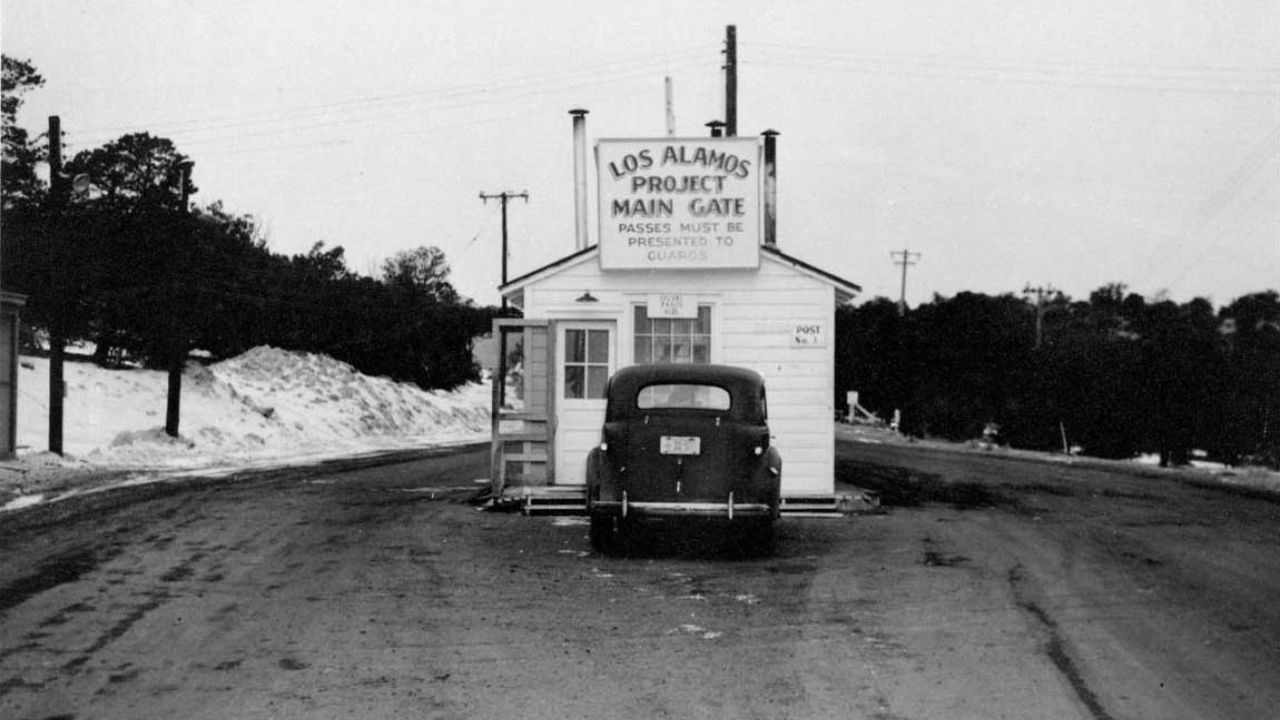

Born into a wealthy Jewish family, Oppenheimer’s life would take him from the affluent neighborhoods of New York City to the dry, desolate landscapes of Los Alamos, New Mexico – the secret site of the Manhattan Project. It was here, under his leadership, that the world’s first nuclear weapons would be built, heralding an age of unparalleled technological prowess and existential dread – the Atomic Age.

Our series will journey through Oppenheimer’s life chronologically, from his early upbringing and education to his quantum leaps in theoretical physics and his vital role in the Manhattan Project. We will examine his internal battles – the ethical quandaries that gnawed at his conscience and his growing regret post the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The series will delve into the political paranoia of the Red Scare era and Oppenheimer’s infamous security hearing, culminating in the examination of his enduring legacy in our modern world.

“Unraveling The Atomic Age: The Life and Legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” is not just a biography of a remarkable scientist; it is a deep dive into a transformative era in human history, marked by unprecedented scientific advancements, ethical dilemmas, and the continual questioning of the role of scientists in society. We invite you to join us on this journey, as we explore the life and times of a man whose influence extended beyond the realms of science, shaping the socio-political landscape of the 20th century and beyond.

As we embark on this intellectual journey, we will unravel the fascinating, complex figure that was J. Robert Oppenheimer – an emblem of the potential and perils of scientific progress. Through his life, we witness the heights of human ingenuity and the depths of its capacity for destruction – a paradoxical narrative that serves as a powerful testament to our collective history.

We look forward to exploring this narrative together, unraveling the nuances, examining the impacts, and reflecting on the lessons of the Atomic Age and the role we all play in the ethical unfolding of scientific progression. It promises to be a journey filled with insights, reflections, and discoveries, as we strive to understand one of the most transformative periods in human history through the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Welcome to the journey of unraveling the Atomic Age.

Oppenheimer: A Genius Born

In the heart of New York City, on the 22nd of April 1904, a boy was born who would grow up to become one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. His name was Julius Robert Oppenheimer, or as he would later be known to the world, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Born into a wealthy Jewish family, his father, Julius Oppenheimer, was a successful textile importer, while his mother, Ella Friedman, was an artist who imbued young Robert with a love of culture and intellectual pursuit.

Their home on Riverside Drive was a world of books and art, a testament to the intellectual curiosity that was instilled in Robert from an early age. It was an environment that nourished his inquisitive nature and enabled his cognitive abilities to flourish. By the time he was a child, he was already showing signs of an exceptional intellect. One anecdote speaks of how a young Oppenheimer, asked by his grandfather what he wanted for his birthday, requested a mineral collection — the first glimmer of a fascination with the natural world that would define his life.

Robert attended the Ethical Culture School in New York, an institution founded on the principles of ethical individualism and social justice. This formative experience nurtured not only his mind but his values too, providing a holistic education that would underpin his later scientific and moral deliberations. He quickly rose to prominence in the school, with his teachers recalling his astounding memory and quick comprehension.

But it was not just science that enthralled the young Oppenheimer. As a teenager, he developed an abiding interest in the classics, mastering Greek and Latin, and delving into the philosophy of Kant and Nietzsche. This blend of scientific rigor and philosophical thought would later shape his worldview and, ultimately, his contributions to science.

Upon graduation from high school, Robert traveled to Harvard University, entering the world of higher education with the same voracious intellectual appetite that had defined his childhood. It was here that his journey to becoming one of the greatest theoretical physicists of his era truly began.

He joined Harvard a year late due to a bout of dysentery he had caught on a geological expedition, but he was undeterred. His brilliance shone brighter than ever, as he absorbed four years’ worth of education in just three. Under the watchful eyes of renowned physicists like Percy Bridgman, Oppenheimer sailed through Harvard, absorbing knowledge like a sponge. He graduated summa cum laude in just three years, securing his place among the top scholars of his generation.

The young Oppenheimer’s focus was on chemistry initially, but his interest soon gravitated toward physics, the science of matter and energy and their interactions. Physics was undergoing a dramatic transformation during these years, with quantum mechanics rewriting the fundamental understanding of the universe.

After Harvard, Robert headed overseas to continue his education at the University of Cambridge’s famed Cavendish Laboratory under the tutelage of J.J. Thomson. Yet, his stay in England was marked by dissatisfaction and unease. Oppenheimer found himself ill-equipped for the laboratory’s experimental nature, a stark contrast from the theoretical perspective he had cultivated at Harvard.

His passion for theoretical physics, however, was reignited when he moved to the University of Göttingen in Germany. Here, under the guidance of Max Born, Oppenheimer found his true calling. He delved deeper into the mysterious world of quantum mechanics, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Werner Heisenberg and Paul Dirac, the pioneers of the field.

Oppenheimer’s doctoral thesis, published when he was just 23, on the ‘continuum of energy states’ was a reflection of the prodigious mind that had begun to make its mark in the world of physics. It was during these years that Oppenheimer developed the theoretical foundations that would later serve him in his most famous role — as the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project.

From his birth in New York City to his emergence as a brilliant scholar in Göttingen, Oppenheimer’s early years were marked by an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and a deep love for scientific inquiry. His intellectual journey was a confluence of diverse influences – from his culturally rich upbringing, his rigorous education at Harvard, to his transformative years in Europe.

These experiences shaped the mind of the young Oppenheimer, preparing him for the trials and tribulations that lay ahead, the ethical dilemmas he would grapple with, and the profound impact he would have on the world. Little did he, or anyone, know at this stage that this genius born would play such a crucial role in the fate of humankind.

Quantum Leap: Oppenheimer’s Theoretical Explorations

In the early 1920s, the foundations of the world were being shaken to the core. A new field of science, quantum mechanics, was rewriting the fundamental rules of the universe, challenging long-held notions about the nature of reality. Among the scientists navigating this seismic shift was a young American physicist named J. Robert Oppenheimer.

After earning his doctorate under Max Born at the University of Göttingen, Oppenheimer began to make his mark in the quantum realm. His doctoral thesis, focusing on the ‘continuum of energy states,’ was an early indication of his prowess in theoretical physics, yet it was only a prelude to the significant contributions he would make to quantum theory.

Returning to the United States in the late 1920s, Oppenheimer accepted dual professorships at the University of California, Berkeley, and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Here, surrounded by the rolling waves of the Pacific and the tranquillity of the Californian landscape, Oppenheimer dove headfirst into the turbulent waters of quantum mechanics.

In 1930, British physicist Paul Dirac had published a revolutionary equation that merged quantum mechanics and special relativity to describe the behavior of the electron. This ground-breaking Dirac equation predicted the existence of antimatter and more specifically, the positron – the electron’s antiparticle counterpart. Oppenheimer seized upon this equation, dedicating himself to further its implications.

As he delved into the mysteries of the Dirac equation, Oppenheimer’s mind was a whirl of differential equations, matrices, and wave functions. Working with his students at Berkeley, he published a series of papers in rapid succession, clarifying and extending Dirac’s work. His most significant contribution in this period was the prediction of ‘electron-positron pair production.’ It was a phenomenon where a high-energy photon could transform into an electron and a positron, essentially turning light into matter and antimatter.

Meanwhile, the world of quantum mechanics was abuzz with debates and discussions. The Copenhagen Interpretation, championed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, was becoming the dominant understanding of quantum mechanics. Oppenheimer, through his interactions with Bohr and other physicists, found himself drawn to this interpretation. He was particularly influenced by Bohr’s principle of complementarity, which suggested that different experimental setups would reveal different, complementary aspects of quantum entities.

Yet, these years of intense scientific exploration were also marked by profound personal tragedy for Oppenheimer. His beloved companion, Francis Fergusson, and his former student, Jean Tatlock, were both lost to him, leaving a significant emotional scar on the otherwise stoic physicist. His exploration of quantum mechanics, as a result, was not just a scientific journey but a personal quest for order amidst chaos, an endeavor to find stability in the probabilistic realm of quantum physics.

A meeting with Albert Einstein in the early 1930s further shaped Oppenheimer’s scientific pursuits. Einstein, although instrumental in establishing quantum mechanics, had grown disillusioned with its inherent randomness and famously said, “God does not play dice with the universe.” This dissenting voice provoked Oppenheimer’s thoughts and strengthened his belief in the Copenhagen Interpretation. Despite Einstein’s concerns, Oppenheimer remained a firm advocate of quantum mechanics, considering it the most accurate theory to describe the microscopic world.

As Oppenheimer’s understanding of quantum mechanics deepened, so did his reputation within the scientific community. He became known not just as a gifted physicist but as a charismatic educator, shaping a generation of physicists who would themselves make significant contributions to the field. His classrooms at Berkeley and Caltech were hothouses of intellectual inquiry, with Oppenheimer firmly at the helm.

Thus, during this period, Oppenheimer’s theoretical explorations elevated him from a bright young scholar to a leading figure in quantum mechanics. His work on the Dirac equation, positron theory, and his steadfast advocacy of the Copenhagen Interpretation all left indelible marks on the landscape of quantum physics. Little did anyone know that this realm of abstract thought, so removed from everyday experiences, would soon come to bear on the most concrete and tragic realities of human existence.

From Academia to Manhattan: The Shift in Focus

During the late 1930s, J. Robert Oppenheimer was an established figure in academia, renowned for his contributions to quantum mechanics. But as the winds of war swept across the globe, his life was to take an unexpected turn. Moving from the abstract heights of theoretical physics, he would soon find himself at the epicenter of a project that would alter the course of human history – the Manhattan Project.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the peaceful serenity of Oppenheimer’s academic world began to crumble. Concerns grew in the scientific community about the prospect of nuclear technology being weaponized, fueled by the discovery of nuclear fission in Germany. In particular, the fear that the Nazis might be capable of developing an atomic bomb became an unsettling specter.

Oppenheimer’s expertise in quantum mechanics and nuclear physics had, until now, been of purely theoretical interest. Yet, with the changing global scenario, his knowledge suddenly became of immense practical significance. In the early 1940s, he was recruited by the U.S. government to work on the development of a weapon that leveraged the destructive power of nuclear fission – the atomic bomb.

The Manhattan Project, as the endeavor was codenamed, represented a radical shift for Oppenheimer. The university classrooms and research laboratories he was familiar with were replaced by a secret laboratory nestled in the isolated desert of Los Alamos, New Mexico. Here, Oppenheimer was not just a physicist, but the scientific director responsible for leading a team of the world’s brightest minds toward a singular, harrowing goal.

Despite no previous experience in leadership roles, Oppenheimer proved surprisingly effective as the director. His charisma and intense focus galvanized the diverse and often headstrong group of scientists. He was not just managing the scientific process, but also the complex human dynamics involved in such a high-pressure, secret project.

Yet, the Manhattan Project posed a moral dilemma for Oppenheimer. The objective of the project was to create a weapon of unprecedented destructive power. As a scientist, Oppenheimer was committed to the pursuit of knowledge. As a human being, he was increasingly tormented by the potential consequences of his work.

His struggles were not just philosophical but also personal. The work at Los Alamos was shrouded in such secrecy that it took a toll on Oppenheimer’s relationships, particularly with his younger brother, Frank Oppenheimer, who was also part of the project. Their sister-in-law, Jackie Oppenheimer, described Los Alamos as a place where “everything was focused on the bomb,” leaving little room for normal life.

Despite these challenges, Oppenheimer remained dedicated to the project. He believed that creating the atomic bomb was necessary to end the war and deter future conflict. His professional focus shifted from theoretical exploration to a singular goal – the successful development and testing of the atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer’s transition from academia to the Manhattan Project was a testament to his adaptability, leadership, and unwavering focus. It marked a significant shift not just in his professional career but also in his personal and ethical perspectives. Yet, he could hardly foresee the profound implications that his involvement would have on his future and the future of humanity. The reverberations of his work in the desert of New Mexico would be felt not just in the concluding chapters of World War II, but would echo throughout the remainder of the 20th century and beyond.

The Manhattan Project: The Making of The Atomic Bomb

In the barren expanses of the New Mexico desert, during the height of World War II, an audacious scientific endeavor was unfolding under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer. This endeavor, known as the Manhattan Project, aimed at a seemingly impossible goal: to harness the destructive power of nuclear fission and construct the world’s first atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project was as the scientific director. A position that called for him to lead some of the brightest minds in physics, chemistry, and engineering in the world, many of whom had been uprooted from their usual academic environments and brought to the remote confines of the Los Alamos laboratory. They were not only charged with solving a scientific problem of colossal magnitude but doing so against the backdrop of a world at war.

The task at hand was monumental. They had to overcome unprecedented scientific and technical challenges in a race against time. Two types of bombs were to be developed: one using plutonium, a man-made element with the atomic number 94, and the other using uranium-235, a naturally occurring isotope.

Each design presented its unique set of challenges. For the plutonium bomb, a technique called implosion had to be invented. The process would require a uniform shock wave to compress a subcritical sphere of plutonium into a supercritical state, initiating a chain reaction. For the uranium-235 bomb, a gun-type fission bomb design was chosen, which would involve shooting a sub-critical piece of uranium-235 into another sub-critical mass to achieve a supercritical state.

To manage these challenges, Oppenheimer adopted an interdisciplinary approach, breaking down the traditional barriers between scientific fields. Physicists, chemists, metallurgists, and engineers worked together, feeding off each other’s insights and expertise. He held frequent review sessions where teams could present their findings, and problems could be tackled collectively. This collaborative spirit became one of the hallmarks of the Manhattan Project under Oppenheimer’s leadership.

However, it wasn’t just the scientific and technical challenges that Oppenheimer had to navigate. The Manhattan Project was a prime example of the complex relationship between science and politics. The endeavor was as much a political and military project as it was a scientific one.

Oppenheimer found himself at the nexus of these forces, grappling with bureaucratic hurdles and political scrutiny while striving to keep the project on track. He liaised with politicians, military personnel, and officials from the Atomic Energy Commission, becoming an effective mediator between the world of science and the corridors of power.

Despite the pressures and the intense secrecy shrouding the project, Oppenheimer proved to be a charismatic and effective leader. He was often seen striding around the Los Alamos site, pipe in hand, deep in thought but always ready to discuss problems or clarify concepts. His unwavering dedication, coupled with his understanding of both the theoretical and practical aspects of the project, earned him the respect of his colleagues.

Finally, in July 1945, their efforts came to fruition with the successful detonation of the first atomic bomb, codenamed “Trinity,” at the Alamogordo Bombing Range in New Mexico. As the shockwave from the explosion rippled across the desert and the mushroom cloud billowed into the early morning sky, Oppenheimer famously recalled a line from the Hindu scripture, Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The Manhattan Project, under Oppenheimer’s stewardship, was a watershed moment in human history, showcasing the extraordinary power of scientific collaboration but also revealing the terrifying potential of scientific discovery when harnessed for destructive ends. It left an indelible mark on Oppenheimer’s life and legacy, transforming him from an academic physicist into a figure of world-historical significance. The making of the atomic bomb was not just a scientific project, but a profound commentary on the intersection of science, politics, and the human condition.

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Age Begins

As the echoes of the first atomic explosion faded over the New Mexico desert in the early hours of July 16, 1945, the world unknowingly stepped into a new epoch – the Atomic Age. In the weeks that followed, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would bear witness to the full magnitude of this new power. At the epicenter of it all was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who had led the Manhattan Project to its terrifying conclusion.

For Oppenheimer, the test at Trinity site marked the culmination of years of intense scientific work. Yet, the success was bittersweet. As he watched the fireball illuminating the desert, he recalled the lines from Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The implications of the new weapon were starting to sink in.

Just a few weeks after the Trinity test, the abstract theories of quantum mechanics and nuclear physics translated into harsh reality. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were decimated by Little Boy and Fat Man, atomic bombs developed under Oppenheimer’s supervision. The instantaneous death of tens of thousands of people, followed by the painful suffering of survivors, brought a new level of horror to warfare.

Oppenheimer’s reactions to these bombings were complex and conflicted. On one hand, the success of the Manhattan Project had effectively ended World War II, perhaps saving countless lives that would have been lost in a protracted war. On the other hand, the devastation caused by the bombs and the ethical implications of their use weighed heavily on him.

The atomic bombings had immediate and far-reaching impacts on science, international politics, and warfare. Scientists, who had traditionally worked in the realm of pure knowledge, had now become key players in geopolitics and military strategy. This shift raised profound ethical questions about the role and responsibilities of scientists. As a key figure in this transformation, Oppenheimer himself grappled with these issues, transitioning from a physicist to a spokesperson for the scientific community in the public sphere.

In the realm of international politics, the Atomic Age signaled the start of a new power dynamic. The United States, as the sole possessor of nuclear weapons, emerged as a superpower. This monopoly was short-lived, however, with the Soviet Union conducting its first successful atomic test in 1949. This development marked the beginning of a global nuclear arms race and the Cold War, fundamentally reshaping international relations and the geopolitics of the 20th century.

In terms of warfare, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki represented a paradigm shift. The immense destructive power of nuclear weapons, capable of annihilating entire cities and causing long-term environmental damage, redefined the nature of warfare. This new reality led to the development of concepts like deterrence and mutually assured destruction, further illustrating the ethical complexities introduced by nuclear weapons.

The Trinity test and subsequent bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not merely historical events, but marked the dawn of a new era – the Atomic Age. J. Robert Oppenheimer, as the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, found himself at the center of these momentous events, grappling with the consequences of his work. These events and their aftermath brought new dimensions to his life and work, casting long shadows that would follow him in the years to come.

Oppenheimer: The Remorseful Architect

In the wake of the cataclysmic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, J. Robert Oppenheimer found himself confronting the moral implications of his work. The world had witnessed the dawn of a new age, one bristling with the promise and peril of atomic power. The architect of this age was not immune to the profound ethical quandaries that this new era presented. Oppenheimer, the brilliant physicist who had once reveled in the beauty of fundamental laws of nature, was now grappling with a haunting image of himself: “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”.

This quote, drawn from the ancient Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita, echoed in Oppenheimer’s mind as he watched the first atomic bomb detonate at the Trinity test site. In the months and years that followed, it would become emblematic of his inner turmoil and growing remorse.

The man who had once pursued knowledge for its own sake was now deeply troubled by the human capacity for destruction that this knowledge had unlocked. The abstract equations and theoretical constructs of his earlier work had materialized into a stark, horrifying reality. This shift from theoretical physicist to a so-called “destroyer of worlds” left Oppenheimer in a state of profound moral reflection.

Oppenheimer’s growing remorse found an outlet in his advocacy for international control of nuclear weapons. He became a vocal proponent of policies that sought to prevent a nuclear arms race and to promote the peaceful use of atomic energy. His public speeches and private counsel to political leaders were characterized by a fervent desire to rein in the destructive potential of the force he had helped unleash.

In 1946, he played a key role in the formation of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), a civilian agency responsible for the oversight of nuclear research and weaponry in the United States. Oppenheimer served as the chief advisor to the AEC, emphasizing the need for transparency, international cooperation, and civilian control.

Despite his significant contributions to the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer’s advocacy for a more restrained approach to nuclear power was met with suspicion and hostility during the Cold War years. His remorse and subsequent advocacy for international control did not sit well with those who viewed nuclear weapons as a necessary deterrent against perceived threats.

In the narrative of Oppenheimer’s life, his transformation into the “Remorseful Architect” marked a pivotal phase. His growing regret and efforts towards nuclear control revealed a man attempting to grapple with the implications of his work, the ethical complexities of scientific progress, and the daunting reality of the Atomic Age.

The image of Oppenheimer, the scientist who quoted from ancient scripture as he witnessed the birth of the Atomic Age, is one of the most enduring of the 20th century. It serves as a poignant reminder of the weighty moral responsibility that accompanies the pursuit of knowledge and the profound impact that individuals can have in shaping the course of history.

Red Scare: The Trial of J. Robert Oppenheimer

The mid-twentieth century in America was a time steeped in tension and fear, as the world’s two superpowers jostled for dominance during the Cold War. A wave of anti-communist sentiment had washed over the nation, spawning an era of suspicion and paranoia known as the Red Scare. In 1954, at the height of this era, one of America’s most celebrated scientists, J. Robert Oppenheimer, found himself in the unlikeliest of positions – on trial for his loyalty to the nation he had helped secure victory in World War II.

Oppenheimer’s security hearing was held behind the closed doors of a nondescript Washington D.C. building. It was a process fraught with intrigue, tension, and undercurrents of personal vendetta. The hearing was led by the Atomic Energy Commission, the same organization that Oppenheimer had advised just years prior, and revolved around his past affiliations with Communist organizations and his stance on the development of the hydrogen bomb.

These accusations stemmed, in part, from Oppenheimer’s past: his association with Communist groups during his younger days, and his opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb. The latter, a stance stemming from his deep-seated moral concerns about the escalating arms race, was viewed with suspicion in an atmosphere charged with fear of the Soviet Union.

The proceedings unfolded over several weeks, with the prosecution painting a picture of Oppenheimer as a security risk, potentially swayed by his earlier leftist inclinations. Friends, family, and colleagues were called to the stand, each one contributing to a portrayal of a complex man caught in the tumultuous currents of history.

The impact of the trial on Oppenheimer’s career and reputation was profound. Stripped of his security clearance, he was effectively exiled from the world of government and military research that he had once played such a vital role in shaping. His reputation was tarnished, with the allegations overshadowing his monumental contributions to the Manhattan Project.

The trial of J. Robert Oppenheimer was more than just an examination of one man’s loyalty. It was a reflection of the Cold War paranoia that gripped America. The nation’s collective fear of Communism led to a stark polarization, where any deviation from the accepted narrative was viewed with suspicion. Oppenheimer’s trial was a manifestation of this fear and paranoia, with one of the nation’s most brilliant minds falling victim to the Red Scare.

Despite the tragic personal consequences for Oppenheimer, his trial brought to light the dangers of unchecked fear and the importance of dissenting voices, even in times of perceived threat. It was a stark reminder of the need for vigilance in safeguarding the values of freedom and openness, particularly in the face of fear and uncertainty.

The trial of J. Robert Oppenheimer remains an iconic episode in the annals of American history, a chilling testament to the power of fear and the tragic consequences that can befall those who dare to speak out against the prevailing winds. The brilliant physicist, once hailed as the father of the atomic bomb, was relegated to the sidelines of the scientific community he had once led, his career and reputation shattered in the crucible of Cold War paranoia.

Legacy of Oppenheimer: The Father of The Atomic Age

When J. Robert Oppenheimer passed away on February 18, 1967, he left behind a complex and profound legacy that continues to reverberate through the fields of science, policy, and society. Often referred to as the “Father of the Atomic Age,” Oppenheimer’s life and work opened up new frontiers in our understanding of the universe, even as it thrust us into a new, unsettling era of destructive potential.

In the realm of science, Oppenheimer’s early work in quantum mechanics and his contributions to the development of nuclear physics established him as one of the leading physicists of his time. His work on the Dirac equation, positron theory, and his role in the development of the atomic bomb expanded our understanding of the fundamental forces that govern the universe. Oppenheimer’s work continues to influence contemporary research in theoretical physics, underpinning the frameworks used to explore the intricacies of the quantum world and the vast expanse of the cosmos.

But perhaps the most significant aspect of Oppenheimer’s scientific legacy is the way in which he navigated the intersection of science and society. His life, characterized by a relentless pursuit of knowledge and a deep sense of responsibility, reflected the promise and peril inherent in scientific advancement. He embodied the paradigm shift that occurred in the mid-twentieth century, as scientists transitioned from detached observers to active participants in shaping the course of history.

In the sphere of policy, Oppenheimer’s experience during and after the Manhattan Project significantly influenced the dialogue on nuclear policy, scientific ethics, and international relations. His fervent advocacy for international control of nuclear weapons, even as he faced suspicion and ostracization during the Red Scare, demonstrated a nuanced understanding of the geopolitical implications of scientific progress. His efforts underscored the need for policy decisions to be informed by scientific understanding, a principle that remains vital in addressing contemporary global challenges, such as climate change and cybersecurity.

Beyond his scientific contributions and influence on policy, Oppenheimer’s life served as a poignant narrative of the ethical dilemmas faced by scientists. His journey from the secluded realms of theoretical physics to the harsh realities of the Atomic Age epitomized the evolving role of scientists in society. His regret over the destructive use of atomic power and his ensuing efforts to prevent a nuclear arms race serve as a potent reminder of the ethical responsibility borne by those at the forefront of scientific discovery.

Today, as we navigate an increasingly complex and interconnected world shaped by rapid scientific and technological advancements, the legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer remains deeply relevant. His life story – a tapestry woven with threads of brilliance, ambition, regret, and resilience – continues to inspire and caution us. It reminds us of the transformative power of scientific knowledge, the moral quandaries it can engender, and the pivotal role of scientists in shaping the course of history. The legacy of Oppenheimer, the father of the Atomic Age, serves as a beacon, illuminating the challenges and responsibilities that accompany our quest to unravel the mysteries of the universe.

Keywords

- Upbringing: The way in which a child is cared for and taught how to behave while they are growing up.

- Affinity: A spontaneous or natural liking or sympathy for someone or something.

- Theoretical physics: Branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions to explain or predict natural phenomena.

- Phenomenon: A fact or situation that is observed to exist or happen, especially one whose cause is in question.

- Quantum mechanics: The branch of mechanics that deals with the mathematical description of the motion and interaction of subatomic particles.

- Positron: An antiparticle of the electron, with the same mass as the electron but possessing a positive charge.

- Transition: The process or a period of changing from one state or condition to another.

- Ethical dilemmas: A moral problem where a decision must be made between two equivalent choices.

- Atomic bomb: A bomb that derives its destructive power from the rapid release of nuclear energy.

- Technical challenges: Difficulties or problems related to the practical use of machines, methods, and the like.

- Cataclysmic: Relating to or denoting a violent natural event.

- Repercussions: An unintended consequence occurring some time after an event or action, especially an unwelcome one.

- Advocacy: Public support for or recommendation of a particular cause or policy.

- Atomic Energy Commission: An agency of the United States government established after World War II to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology.

- Hostility: Unfriendliness or opposition.

- Paranoia: Unjustified suspicion and mistrust of other people.

- Affiliations: The state of being closely associated with or connected to an organization, company, or individual.

- Inclinations: A person’s natural tendency or urge to act or feel in a particular way.

- Exiled: Expelled and barred from one’s native country, typically for political or punitive reasons.

- Manifestation: An event, action, or object that clearly shows or embodies something abstract or theoretical.

- Polarization: Division into two sharply contrasting groups or sets of opinions or beliefs.

- Prevailing winds: A wind from the direction that is predominant at a particular place or season.

- Fundamental forces: In physics, they are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions: gravity, electromagnetism, strong nuclear force, and weak nuclear force.

- Underpinning: A solid foundation laid below ground level to support or strengthen a building.

- Geopolitical: Relating to politics, especially international relations, influenced by geographical factors.

- Ostracization: The process of excluding or being excluded from a society or group.

- Nuanced: Characterized by subtle shades of meaning or expression.

- Epitomized: Be a perfect example of.

- Resilience: The capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness.

- Quandaries: A state of perplexity or uncertainty over what to do in a difficult situation.

Key Takeaways

- The Promise and Peril of Scientific Advancement: Oppenheimer’s story is a stark reminder of the power of scientific knowledge to shape the world, both for better and for worse. His contributions to nuclear physics led to an unprecedented leap in our understanding of the universe, but also unlocked a destructive power that continues to pose a significant global threat.

- The Ethical Responsibility of Scientists: The regret Oppenheimer expressed over the destructive use of atomic power illustrates the moral and ethical dilemmas inherent in scientific work. Scientists must not only strive to advance knowledge, but also consider the potential implications and applications of their research.

- The Intersection of Science and Policy: Oppenheimer’s involvement in the Manhattan Project and subsequent advocacy for nuclear control demonstrate the crucial role scientists can and must play in shaping policy. Scientific understanding is an indispensable element in informed decision-making on issues of global importance.

- The Impact of Socio-Political Context: The Red Scare and Oppenheimer’s trial underscore the profound influence of socio-political context on individual lives, even those of prominent scientists. It serves as a reminder of the need for vigilance against fear and suspicion undermining basic freedoms and principles.

- Resilience in the Face of Adversity: Despite the professional and personal challenges he faced, including the dramatic fallout from his security hearing, Oppenheimer continued to contribute to science and policy. His resilience offers a lesson in perseverance and commitment to one’s convictions.

- The Lasting Influence of a Scientist: Oppenheimer’s legacy extends far beyond his work on the atomic bomb. His early contributions to quantum mechanics continue to inform research in physics. Additionally, his reflections on the ethical implications of scientific advancement continue to inspire debate on the responsibilities of scientists.

- Understanding the Human behind the Scientist: Oppenheimer’s story serves as a reminder that behind every significant scientific advancement is a human with personal beliefs, biases, and faults. It is essential to remember the human aspect of scientific progress to appreciate the nuances and complexities involved.

In conclusion, the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer serves as a potent exploration of the intersection of science, ethics, and policy. It is a testament to the transformative power of scientific discovery, the ethical quandaries such advancements can pose, and the profound influence of socio-political contexts on individuals and their work.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Oppenheimer choose to study theoretical physics, specifically?

Oppenheimer was naturally drawn towards the foundational questions of the universe, which is a major focus in theoretical physics. Additionally, during the early 20th century, theoretical physics was witnessing dramatic advancements, particularly in quantum mechanics. The prospect of being part of such groundbreaking research could also have attracted him. However, it’s important to remember that career choices often reflect a blend of personal interest, curiosity, and the influences of mentors or notable thinkers in the field, and Oppenheimer’s case was likely no different.

What was Oppenheimer’s relationship with other leading scientists of his time?

Oppenheimer had relationships with many leading scientists of his era, both as colleagues and sometimes as competitors. His involvement with the Manhattan Project led him to work with a diverse group of leading physicists, including Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi. His intellectual engagements with these individuals were profound, often filled with rich scientific debate and collaboration.

How did Oppenheimer’s work influence the field of theoretical physics beyond the atomic bomb?

Before his work on the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer had made significant contributions to the field of quantum mechanics, particularly his work on the Dirac Equation and positron theory. These early contributions had a significant impact on the field and continue to be relevant to contemporary research in quantum physics.

How did the public perceive Oppenheimer during his lifetime, especially during and after the Manhattan Project?

Public perception of Oppenheimer was complex and changed dramatically over time. During the Manhattan Project, he was seen by many as a war hero, leading the effort to develop a technology that could potentially end the war. However, after the war, especially during the Red Scare, public opinion shifted, and Oppenheimer was often portrayed as a suspicious figure due to his past affiliations and advocacy for nuclear control.

How did Oppenheimer’s work impact the development of nuclear energy for peaceful uses?

Oppenheimer was a strong advocate for the peaceful use of nuclear technology. After the war, he became a prominent voice in advocating for international control of nuclear power and a shift away from weapons development. These efforts had a profound impact on the conversation around nuclear energy and helped to promote its use for peaceful purposes, such as power generation.

What were some of the main criticisms of Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project?

Oppenheimer faced criticism on multiple fronts. Some argued that he should have done more to prevent the military use of nuclear technology. Others, especially during the Red Scare, criticised him for his previous left-leaning affiliations and his later advocacy for nuclear control, which was seen by some as being too lenient towards the Soviet Union.

How did Oppenheimer’s personal life influence his professional career?

Oppenheimer’s personal life had a profound impact on his professional career. His relationships, interests, and personal beliefs often informed his approach to scientific research and his views on the application of science in society. Notably, his personal affiliations were a key factor in the controversy that surrounded him during the Red Scare.

Did Oppenheimer ever express regret over his involvement in the development of the atomic bomb?

Yes, Oppenheimer expressed deep regret over the use of the atomic bomb on civilian populations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He famously quoted from the Bhagavad Gita, saying “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Following the war, he became a strong advocate for international control of nuclear weapons to prevent their use in future conflicts.

How did the scientific community react to Oppenheimer’s security hearing and the subsequent revocation of his security clearance?

The scientific community’s response to Oppenheimer’s security hearing was mixed. Some stood by him, recognizing the political nature of the charges. Others, however, distanced themselves due to the climate of suspicion and fear during the Red Scare. The revocation of his security clearance was widely seen as a damaging blow to scientific freedom.

What is Oppenheimer’s most lasting contribution to science and society?

While Oppenheimer’s role in the development of the atomic bomb is perhaps his most widely known contribution, his influence extends far beyond that. His early work in quantum mechanics continues to inform contemporary physics, and his experience serves as a potent reminder of the ethical responsibilities of scientists. His advocacy for the peaceful use of nuclear energy and international control of nuclear weapons has also had a profound impact on policy and continues to inform the debate on nuclear technology.

Myth Buster

Myth: Oppenheimer single-handedly built the atomic bomb

Reality: While Oppenheimer played a critical role in the Manhattan Project, it was a collective effort involving thousands of scientists, engineers, and support personnel. Oppenheimer’s main contribution was as a leader and organizer of the project, rather than as the sole inventor of the atomic bomb.

Myth: Oppenheimer was a Communist

Reality: Oppenheimer was involved with left-leaning political groups in the 1930s, but there is no evidence that he was a member of the Communist Party. During the Red Scare, he was scrutinized for these associations, but no conclusive proof was ever found.

Myth: Oppenheimer was a traitor

Reality: The 1954 security hearing that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance was largely politically motivated and was not based on solid evidence of espionage or treason. Oppenheimer was a vocal critic of the hydrogen bomb development and advocated for international control of nuclear weapons, which put him at odds with some powerful figures in the government and military.

Myth: Oppenheimer regretted his work on the atomic bomb

Reality: Oppenheimer expressed regret over the military use of the bomb and the destruction it wrought, particularly on the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, he did not necessarily regret his work on the Manhattan Project itself, which he saw as necessary during a time of war.

Myth: Oppenheimer was a pacifist

Reality: While Oppenheimer became a strong advocate for nuclear arms control after the war, it would be incorrect to label him a pacifist. He supported the development of the atomic bomb during World War II and believed in its initial use to end the war.

Myth: Oppenheimer’s work was solely focused on nuclear physics

Reality: Prior to the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer made significant contributions to quantum theory and cosmology. His work on the so-called “Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit” in neutron stars is a key part of astrophysics.

Myth: Oppenheimer was always against the development of the hydrogen bomb

Reality: Oppenheimer initially opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb, arguing it was not feasible and would only lead to an arms race. However, once it became apparent that such a bomb was possible, and with evidence of Soviet nuclear development, he did not stand in the way of its development.

Myth: Oppenheimer was a loner and an outcast among scientists

Reality: Oppenheimer was respected by many of his scientific peers. Even after his security clearance was revoked, many in the scientific community continued to respect him and his contributions to science.

Myth: Oppenheimer’s scientific career ended after his security clearance was revoked

Reality: While the revocation of his security clearance severely limited his ability to contribute to government-related nuclear research, Oppenheimer continued to work in academia and remained an influential figure in science and policy.

Myth: Oppenheimer was solely a physicist

Reality: Oppenheimer was indeed a physicist, but he also had wide-ranging interests in philosophy, literature, and Eastern religions. His holistic approach to knowledge and his philosophical reflections on science and ethics contributed significantly to his viewpoints and his overall approach to science and its role in society.

Test Your Knowledge

Where was J. Robert Oppenheimer born?

A. New York

B. Chicago

C. San Francisco

D. Los Angeles

A

What field of study did Oppenheimer focus on in his early career?

A. Nuclear physics

B. Quantum mechanics

C. Astrophysics

D. Chemistry

B

What was Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project?

A. He was a technical consultant

B. He was the project’s scientific director

C. He was responsible for the project’s funding

D. He was the head engineer

B

Which famous quote did Oppenheimer recite upon witnessing the first successful atomic bomb test?

A. “We have become the architects of annihilation”

B. “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”

C. “With great power comes great responsibility”

D. “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”

B

Why was Oppenheimer’s security clearance revoked in 1954?

A. For revealing state secrets

B. For suspicions of communist affiliations

C. For opposing the development of the hydrogen bomb

D. For ethical concerns regarding the use of the atomic bomb

B

Which university did Oppenheimer attend for his undergraduate studies?

A. Harvard University

B. California Institute of Technology

C. Princeton University

D. University of Cambridge

A

What was the name of the first successful atomic bomb test?

A. Fat Man

B. Little Boy

C. Trinity

D. Enola Gay

C

In what area did Oppenheimer advocate for international control after World War II?

A. Nuclear weapons

B. Quantum mechanics research

C. Space exploration

D. Artificial intelligence development

A

What role did Oppenheimer play in the development of the hydrogen bomb?

A. He led its development

B. He played no role in its development

C. He was initially opposed but did not obstruct its development

D. He actively sabotaged its development

C

Related Articles about the Nuclear Age

Unveiling the Atom: The Manhattan Project’s Deep Impact on World History

Albert Einstein: The Maverick Mind that Revolutionized Physics

Leo Szilard: The Atomic Pioneer’s Crusade for Peace

The Ethical Odyssey: Exploring Morality in the Course of Scientific Discovery

Los Alamos National Laboratory: Navigating the Past, Present, and Future of Scientific Innovation

The Cold War: Superpowers in the Ballet of Weaponry

Nuclear Proliferation: The Ever-Present Global Challenge

Interplay of Science and Politics: The Unsung Dance of Progress

Enrico Fermi: Mastermind Behind the Nuclear Age

From Atomic To Thermonuclear: A Detailed Examination of Nuclear Weapon Evolution

The Unforgotten Echoes: Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s Tale of Nuclear Devastation and Human Resilience

Living Under the Mushroom Cloud: The Psychological Impact of the Nuclear Age

Nuclear Fallout: Unmasking the Invisible Threat to Health and Environment

The Power and Peril of Nuclear Energy: A Balanced Perspective

Radiation Sickness: Unveiling the Hidden Costs of the Nuclear Age

From Darkness to Light: Lessons from Chernobyl and Fukushima

Deciphering the Nuclear Waste Conundrum: The Path Towards Sustainable Solutions

Guarding the World from Nuclear Threats: International Laws for Nuclear Disarmament

Journey to Peace: Unraveling the Path to Global Nuclear Disarmament

Culture Echoes of the Atomic Age: Artistic Narratives in the Nuclear Era

0 Comments