English Plus Magazine

Dive into a world of ideas, stories, English and discovery.

Coming Soon!

Some of these articles are already published, and some will be published very soon. Check out the new articles below…

Danny's Column

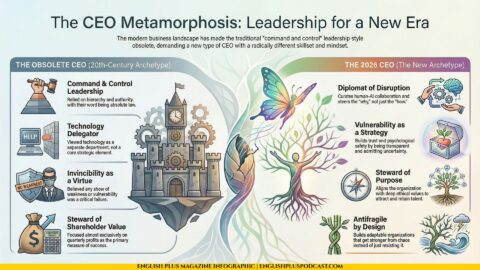

The Guide | Algorithm-Proof Your Soul: How to Thrive When Machines Do the Rest

Let’s be honest about something right now. You feel it, don’t you? That low-level hum of anxiety when you open your news feed. You see a headline about a new AI model that can write code, generate art, or diagnose diseases better than a human doctor. And for a split second, you wonder: Where does that leave me?

You aren’t alone in that feeling. It is the defining anxiety of our time. We are living through a shift as massive as the Industrial Revolution, but it is happening ten times faster. The ground is moving under your feet, and you are trying to find something solid to hold onto.

But here is the truth that the panic headlines won’t tell you: You don’t need to compete with the machines. You lose that fight every time. An algorithm will always process data faster than you. It will always calculate odds better than you. It will always work harder, longer, and cheaper than you.

If you try to be a better machine than the machine, you are obsolete.

The strategy—the only winning strategy—is to double down on the things the machine cannot do. We are going to algorithm-proof your soul. We are going to take the very things that make you human—your focus, your boundaries, your empathy, and your resilience—and we are going to sharpen them into tools you can use to build a fortress around your career and your mental health.

We have four areas to cover today. This isn’t theory. This is a survival kit. So, let’s get to work.

Part 1: The “Deep Work” Advantage

Let’s start with the most critical asset you own: your attention.

In a world where AI can produce “average” content in seconds, the value of average has dropped to zero. If an AI can write a mediocre email, a basic blog post, or a standard report in three seconds, nobody is going to pay you to do it in three hours. The baseline has been raised.

This means the only work that matters now is work that requires complex thought, nuance, and high-level creativity. This is what Cal Newport calls “Deep Work.” It is the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task.

Here is the problem: most of you have forgotten how to do this. We have trained our brains to function in a state of constant, shallow busyness. We check emails every five minutes. We slack. We scroll. We multitask. We are skimming the surface of our capabilities.

If you want to thrive in the age of automation, you have to reclaim the ability to go deep. Deep work is the new superpower. It is the only way you produce things that are too complex for an algorithm to mimic.

So, how do you do it? I’m not telling you to go live in a cave. I’m giving you a protocol.

First, you need to schedule deep work like a medical appointment. You cannot wait for inspiration. You cannot wait for “free time.” Free time does not exist. You have to carve it out. Start with ninety minutes a day. That is the baseline. Ninety minutes where you are unreachable. No phone. No email. No “just checking.”

During these ninety minutes, you tackle the hardest thing on your plate. The thing that requires you to think until your brain hurts. That discomfort you feel when you are trying to solve a hard problem? That is the feeling of value being created. That is the feeling of you outrunning the algorithm.

Second, you need to embrace boredom. This sounds counterintuitive, but listen to me. When you are standing in line at the grocery store, or waiting for the elevator, what do you do? You pull out your phone. You can’t stand ten seconds of inactivity.

By doing this, you are wiring your brain to crave distraction. You are killing your attention span. If you cannot be bored for five minutes, you cannot do deep work for two hours. Practice doing nothing. Let your mind wander. That is where the connections happen. That is where the human spark lives.

The bottom line on this is simple: Shallow work is for robots. Deep work is for humans. If you are constantly distracted, you are voluntarily lowering your IQ to a level where an algorithm can replace you. Don’t let that happen.

Part 2: Digital Boundaries

Now, you can’t do deep work if you are fighting a losing war against the “attention economy.”

You need to understand what you are up against. You are not just “lacking willpower.” You are fighting against supercomputers employed by the wealthiest companies in human history, designed by teams of behavioral psychologists, with the sole purpose of keeping your eyes glued to a screen.

They want your outrage. They want your envy. They want your fear. Because that is what keeps you scrolling. And when you are scrolling, you are not creating. You are not leading. You are not living. You are just a data point.

You need to build a defense system. You need digital boundaries. And I don’t mean “trying harder” to stay off your phone. Willpower is a finite resource. You need systems that don’t rely on willpower.

Here is your strategy: Friction.

Tech companies spend billions to remove friction. They want “one-click” everything. They want auto-play. They want infinite scroll. Your job is to reintroduce friction.

Make it hard to do the bad thing.

Step one: grayscale your phone. Turn the screen black and white. Suddenly, Instagram doesn’t look so appealing. The dopamine hit of those bright red notification badges disappears. It turns your phone back into a tool, rather than a toy.

Step two: remove the infinite pools. If an app has an infinite scroll—Twitter, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram—get it off your home screen. Better yet, get it off your phone entirely. If you need to check these things for work, do it on a desktop computer. Make it a deliberate action, not a nervous tic.

Step three: The “Phone Foyer” method. When you walk into your house, your phone stays at the door. Or it goes in a designated bowl. It does not go into the bedroom. It does not go to the dinner table. You physically separate yourself from the device.

Why does this matter for the age of automation? Because the algorithm feeds on your passivity. It wants you to be a consumer. To survive this shift, you must be a producer. You must be an active participant in your own life. Every minute you spend doom-scrolling is a minute you aren’t sharpening your skills, connecting with your family, or resting your mind.

You are the CEO of your attention. Stop letting random engineers in Silicon Valley run your company.

Part 3: The Empathy Gap

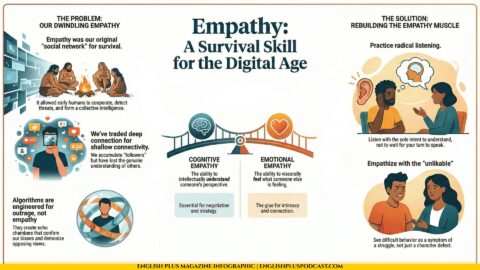

Let’s move on to your safety net. If deep work is your offense, and boundaries are your defense, then Empathy is your moat. It is the protective barrier that surrounds your value.

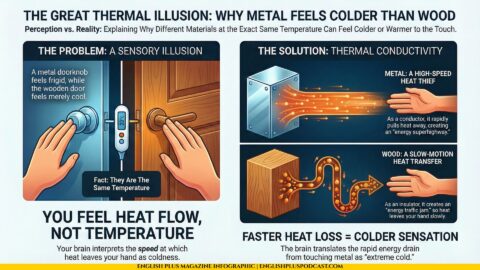

There is a lot of talk about AI having a high IQ. It can pass the bar exam. It can ace medical boards. But it has an EQ—Emotional Intelligence—of zero.

It can simulate empathy, sure. It can say, “I am sorry to hear that.” But it doesn’t care. It doesn’t understand the heavy silence in a negotiation. It can’t read the room. It can’t look a client in the eye and make them feel understood.

This is the “Empathy Gap.” And this is where you win.

As machines take over the technical, logical, and analytical tasks, the value of human connection is going to skyrocket. We are already seeing it. We crave connection. We crave leadership. We crave someone who can navigate the messy, irrational, emotional reality of dealing with other people.

If you want to be indispensable, you need to stop obsessing over technical skills—which change every six months—and start obsessing over human skills.

How do you execute this?

First, become a master listener. And I don’t mean waiting for your turn to speak. I mean active, radical listening. When you are talking to a colleague or a client, put everything else away. Listen to what they are saying, but also listen to what they are not saying. What are they afraid of? What do they really want? An AI listens to text. You listen to subtext.

Second, focus on synthesis and leadership. AI is great at providing options. It is terrible at making decisions. It can give you ten marketing strategies, but it can’t tell you which one fits the soul of your company. It can’t rally a team when morale is low. It can’t mediate a conflict between two managers who hate each other.

Position yourself as the person who connects the dots. The person who bridges the gap between the data and the human experience.

Third, cultivate “irrational” kindness. AI is optimized for efficiency. Humans are optimized for connection. Do things that don’t scale. Send a handwritten note. Remember a birthday. Call someone just to check in, with no agenda. These are inefficient actions. And because they are inefficient, they signal high value. They signal humanity.

In a transactional world run by algorithms, being relational is a revolutionary act. It makes you sticky. Clients leave vendors; they don’t leave partners. Be a partner.

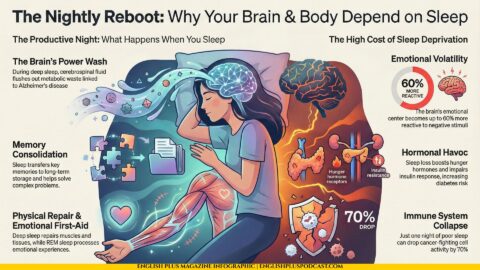

Part 4: Handling “Future Anxiety”

Finally, we need to address the elephant in the room. The fear.

I know some of you are listening to this and you are nodding, but deep down, there is a knot in your stomach. You are worried about your mortgage. You are worried about your kids’ future. You are worried that no matter what you do, the wave is coming to wash you away.

That is “Future Anxiety.” It is the paralysis that comes from trying to predict the unpredictable.

Here is the stoic truth you need to swallow: You cannot control the speed of technological change. You cannot control what OpenAI or Google releases next week. You cannot control the economy.

Worrying about these things is like worrying about the weather. It is a waste of energy that you could be using to build your shelter.

You need to shift your focus from “What if?” to “What is.”

“What if I lose my job in five years?” That is a useless question. It breeds panic.

“What skills can I learn today that will make me more adaptable?” That is a useful question. It breeds action.

The antidote to anxiety is action.

You need to adopt a mindset of “radical adaptability.” The days of having one career for forty years are over. That is gone. You are going to have five careers. You are going to have to reinvent yourself.

This shouldn’t scare you; it should liberate you. It means you are never stuck. It means you are always in beta mode.

Here is a technique to manage this anxiety: The “Worst-Case Scenario” drill.

When the fear spikes, stop and look at it. Define the absolute worst-case scenario. Let’s say AI makes your current job obsolete. Okay. Then what? You lose your job. Then what? You have savings? You have a network? You have skills? You could move? You could do something else?

Usually, when you shine a light on the monster, you realize it is just a shadow. You realize that even in the worst case, you are still you. You are still resilient. You have survived 100% of your bad days so far. You will survive this too.

Do not let the fear of the future rob you of the present. The irony is that the more anxious you are, the less creative you are, and the less creative you are, the more vulnerable you are to being replaced.

To be safe, you must be bold.

The Bottom Line

Let’s bring this home.

The age of automation is not a judgment on your worth. It is a challenge to your growth. It is forcing us to ask the question: What is a human for?

If your answer was “to process data” or “to answer emails,” then yes, you are in trouble. But I don’t believe that is what you are for.

You are here to create. To connect. To solve problems with empathy. To lead with courage. To do the deep, messy, beautiful work that no machine can ever touch.

The algorithm is a tool. It is a hammer. You are the carpenter. Do not let the hammer build the house.

Here is your assignment for today:

Pick one of the strategies we talked about.

Maybe you schedule that ninety-minute deep work block for tomorrow morning.

Maybe you turn your phone to grayscale right now.

Maybe you make that phone call to a client just to ask how they are doing as a human being.

Pick one thing. And execute.

Don’t just listen to this and nod. Knowledge without application is just noise. And we have enough noise.

Go out there and be undeniably, unapologetically human.

I’ll see you next time.

English Plus Magazine

The Architecture of Gratitude: How to Escape the Hedonic Treadmill & Find Joy

Why does the holiday “high” fade so fast? Discover the science of the Hedonic Treadmill and learn how to build a structural foundation of gratitude that lasts beyond New Year’s.

Winter Solstice Meaning: How to Embrace Dormancy & The Return of the Light

Why do we fear the dark? Explore the spiritual and psychological meaning of the Winter Solstice. Learn why “dormancy” is necessary for growth and how to find peace in the longest night of the year.

365 Days of Spirit: Dismantling the “Holiday Container” & Hacking Kindness

Why limit kindness to December? Discover the psychology of the “Holiday Container” and learn practical strategies to carry the spirit of generosity, patience, and gathering into the rest of the year.

Check-Box Charity vs. Effective Altruism: How to Make Your Donation Count

Are you suffering from “check-box charity”? Discover the philosophy of Effective Altruism and learn how to move beyond temporary relief to fund systemic change. Stop buying guilt-relief and start investing in impact.

The Universal Flame: The History and Psychology of Winter Lights (From Yule to Hanukkah)

Why do we light candles in winter? Explore the anthropology of the Advent candle, Menorah, Diya, and Yule log. Discover the shared human history of combating darkness with light.

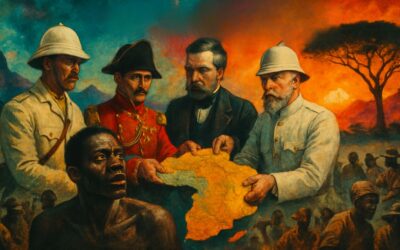

Beyond the Scramble: Overcoming Artificial Borders Through 21st-Century Cooperation

The “Scramble for Africa” & Sykes-Picot created borders that sparked conflict. This article pivots to the solutions: cross-border economic zones, the AU, and cultural festivals that are making those lines irrelevant.

The Missing Pieces: How Cultural Repatriation Is Building a New Future

Move beyond the “stolen art” debate. Discover how cultural repatriation is not an end, but a beginning for healing cultural trauma, building mutual respect, and forging new, equitable global partnerships.

The Selfish Reason to End Poverty: An Economic Case for a Better World

Fighting poverty isn’t just charity; it’s a smart investment. Discover how eradicating poverty boosts economic growth, creates new markets, and builds a more stable and prosperous society for everyone.

The Brain on Poverty: How Scarcity Taxes Our Mental Bandwidth

Poverty isn’t a character flaw; it’s a cognitive burden. Explore the science of how chronic stress and scarcity impact brain function, decision-making, and the ability to plan for the future.

Beyond Charity: The Innovations Reinventing the Fight Against Poverty

Discover the groundbreaking solutions changing how we fight global poverty. Learn about microfinance, Universal Basic Income (UBI), and mobile money—unconventional tools that empower, not just aid.

The Hidden Blueprint: How Global Systems Keep Nations Poor

Why do poor countries stay poor? Explore the systemic reasons, from colonialism’s economic legacy and unfair trade rules to debt traps, and discover how the global economy can perpetuate poverty.

The Many Faces of Poverty: Why Income Is Only Half the Story

Poverty isn’t just about a lack of money. Explore the concept of multidimensional poverty and discover why access to healthcare, education, and clean water reveals the true reality of global inequality.

Also in English Plus Magazine

Mini Podcasts Network

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Stories

The Crow and the Pitcher: A Lesson in Ingenuity from Aesop’s Fables

Discover the timeless Greek fable “The Crow and the Pitcher” from Aesop’s Fables, a story about problem-solving and clever thinking. Learn about its origin, meaning, and lasting impact.

Exploring Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon: Themes, Legacy, and Impact

Discover the rich themes, legacy, and impact of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. Learn about this celebrated novel’s exploration of identity, family, and heritage.

The Myth of Amaterasu and the Cave: A Japanese Legend of Light and Darkness

Discover the Japanese myth of Amaterasu and the Cave, where the sun goddess hid away, casting the world into darkness. Learn how this tale reflects themes of light, unity, and renewal in Japanese culture.

The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki: A Timeless Tale of Tradition and Change

Discover the enduring charm of The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki. Explore how this classic novel captures the tension between tradition and modernity in pre-war Japan.

The Lost City of Atlantis: Myth, Legend, and Ancient Greece

Discover the legend of Atlantis, the lost city described by Plato. Explore the origins of the myth, theories about its location, and its enduring influence on culture.

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame: Victor Hugo’s Masterpiece of Love and Tragedy

Explore the timeless themes of love, fate, and compassion in Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Discover how this immortal work of literature still resonates with readers today.

Spectrum Radio Mixes

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.